BMC Medical Education volume 25, Article number: 812 (2025) Cite this article

Medical students often encounter challenges in maintaining healthy habits. The Preventive Remediation for Optimal MEdical StudentS (PROMESS) project seeks to support students to adopt healthier lifestyles throughout their curriculum by implementing a program focused on three modules (stress, sleep, and physical activity). Prior to implementation, it was essential to gain insights into students' needs. For this purpose, a comprehensive approach was adopted to ensure that the proposed program aligns with students’ needs, to identify barriers and facilitators for implementation, to propose adjustments, and to test the program.

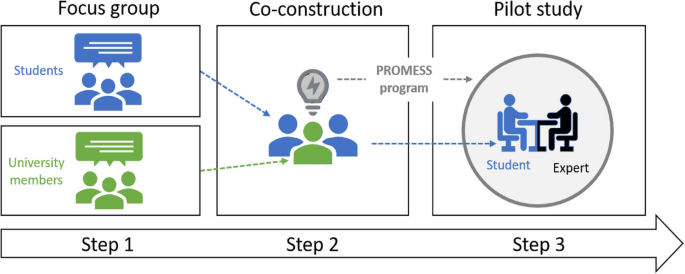

A three-step study was conducted. First, two focus groups sessions, one involving students and the other involving university staff members were conducted to identify medical students' needs and obstacles to change regarding their health. After verbatim transcription, a framework thematic analysis was performed with the use of MAXQDA. Second, a co-construction workshop was conducted with participants from both groups to develop the PROMESS program. Third, some of the medical students who participated in the prior steps tested the co-constructed program. The study was conducted at the Lyon-Est Faculty of Medicine (France, IRB2023070404).

(i) The medical students cited a heavy academic workload and demanding internships as the main factors that contribute to their limited selfcare, heightened stress levels and sleep disruptions, and reduced physical activity. The university staff members noted that students struggled to acknowledge their needs, accept limitations, and seek assistance.

(ii) The participants provided advice for adapting PROMESS program to the students’ specific needs (e.g., individualized advice, one-on-one meetings, peer coaching, and signing a commitment contract).

(iii) The students who tested the program reported being more aware of their health behaviors and reported improvement in stress levels, sleep, and physical activity. They believed that the changes could be long-lasting.

This study identified barriers to changes in medical students’ behaviors that affect their health. The co-construction workshop and the pilot study facilitated program development and enhanced its feasibility and acceptability for broader implementation. This three-step approach highlights the importance of engaging various stakeholders to craft complex health interventions for medical students.

Medical students have to shoulder a heavy workload and are exposed to challenging situations during their curriculum, which can make the implementation of selfcare practices and a healthy lifestyle challenging. An unhealthy lifestyle may impair their wellbeing, quality of life, health, and performance. Previous studies have reported that medical students encounter major issues related to three health behavior domains: stress [1,2,3], sleep [4,5,6], and physical activity [7, 8]. Despite these issues being well-known and widespread and many researchers and clinicians having raised concerns over a long period of time, the solutions offered to medical students are still insufficient to address the full extent of these problems. Accordingly, a recent systematic review has concluded that selfcare education is poorly recognized, adopted, and integrated into medical curriculum [9]. Thus, it remains crucial to explore new solutions aimed at promoting a healthy lifestyle during medical curricula to prevent the emergence of the aforementioned issues among medical students.

This support could be provided through the implementation of programs that enhance medical students' skills to adopt health-promoting behaviors such as effective stress management tools, good sleep habits, and regularly engaging in physical activity [10]. However, no such multi-dimensional programs have been explored in medical students' curriculum. This gap in the literature may be due to the difficulty of designing complex interventions that encompass several health domains. To address this challenge, O'Cathain and collaborators (2019) have offered guidance for the design of complex interventions. They advise that intervention development should be viewed as a dynamic iterative process that includes drawing on existing theories and research evidence, involving stakeholders, undertaking primary data collection, and implementing iterative development cycles to refine the intervention [11]. These steps will ensure the relevance, feasibility, and effectiveness of an intervention. Following O'Cathain' major guidelines, the present study developed a complex intervention entitled Preventive Remediation for Optimal MEdical StudentS (PROMESS), which seeks to support students to adopt healthier lifestyles throughout their curriculum by implementing an adapted preventive program focused on stress, sleep, and physical activity.

O'Cathain and collaborators advise that interventions should be grounded in existing theories and research evidence. Through reliance on the information, motivation, and behavioral skills (IMB) model [12], which was designed to explain and predict health behaviors [13, 14], the PROMESS project aims to help medical students to adopt healthier lifestyles throughout their curriculum. This theoretical framework comprises three essential components. First, to change behaviors, individuals must have accurate and comprehensive information regarding health issues. Second, interventions should target personal attitudes, social norms, and perceived risk to enhance motivation. Third, interventions should develop and reinforce the practical skills and self-efficacy required to perform the health behaviors. In addition, the PROMESS program should incorporate experimental evidence of behavior change. Webb and collaborators have determined that the most effective methods include behavioral incentives from an expert or research assistant, social encouragement, goal or target setting, personalized messages, change planning, and the targets’ self-monitoring of their behaviors [15].

Drawing from the IMB theoretical model and insights gleaned from Webb's meta-analysis, our team envisaged an intervention geared towards cultivating healthier lifestyles among medical students. This intervention is structured in three modules, each featuring guidance from an expert in stress, sleep, or physical activity, to assist students with adopting healthier habits. The intervention includes multiple sessions where the experts will share educational content on each module and introduce key principles of well-established interventions. These sessions will also provide a platform for students to discuss their personal challenges related to each module to facilitate the identification of their needs. Personalized advice and goal-setting aimed at inspiring and empowering students to adopt healthier lifestyles should stem from these discussions.

While it is anticipated that it will prove effective, the actual impact, relevance, and feasibility of this projected intervention within the context of medical education is uncertain. Involving stakeholders in project conception and collecting primary data are crucial steps to ensure that the intervention is customized to address the specific needs of the participants [11]. Involving direct stakeholders, such as medical students, is one means to ensure that the intervention will be closely aligned with their needs and expectations. In addition, it appears to be essential to understand the environment and the context in which they operate [11]. This can be accomplished by involving additional stakeholders from the medical students’ environment, such as university staff members. Finally, before a large-scale implementation of the intervention, it is important to collect primary data, which can be done by conducting a pilot study. These steps allow to refine the intervention before its widespread implementation [11].

The present study aims to identify the health behavior-related needs of medical students to design an effective tailored intervention for them and to evaluate the feasibility of the PROMESS program. The specific objectives were 1) to ensure that the proposed program aligns with the students'needs, 2) to identify barriers and facilitators to implementation, 3) to propose adjustments to the activities based on the identified barriers and facilitators, and 4) to test the intervention with a limited number of participants.

This study is the first part of a larger research project called PROMESS (Preventive Remediation for Optimal MEdical StudentS), which was designed to enhance the quality of life and performance of medical students. The PROMESS project aims to implement a multi-modal health promotion program tailored to medical students’ needs. Three modules have been planned for the program. During each module, an expert in stress, sleep, or physical activity will advise the students and help them to adopt a healthier lifestyle.

A three-step study was conducted. First, two focus groups involving medical students and university staff members were conducted to identify the health challenges encountered by medical students and how to address them. Second, a co-construction workshop was set in place with both groups to adapt the PROMESS program. Third, the medical students who participated in the prior steps tested the program to evaluate its effectiveness and feasibility (Fig. 1).

Study design. In the first step, two focus groups were formed to identify medical students' needs and obstacles medical students encounter. The first group consisted of undergraduate medical students and the second group of university faculty members directly involved in the health of medical students. The second step was a co-construction workshop to develop the PROMESS program. In the third step, some medical students who had participated in the previous steps piloted the PROMESS program

Two investigators (BV and LB) provided written information, collected signed written consent forms, and enrolled participants. No participants had any prior relationship with the moderators before the beginning of the study. The participants did not receive financial compensation for their participation. The study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and approved by a local ethics committee (Lyon, France IRB 2023070404). All the study steps were conducted in a quiet room at the Lyon-Est Faculty of Medicine (University of Lyon 1, France).

Two focus groups were formed to explore participants’ perspectives, with the purpose of understanding the issues and needs of the students; their interest in health interventions related to sleep, stress, and physical activity; and their use of existing university health infrastructure. Two moderators (female, LB, a graduated medical student, and BV, a researcher with a master’s degree) guided the session with the use of predefined interview guides (medical students; Additional file 1, university staff members; Additional file 2) that they had developed with the help of SS (female, PhD, researcher), JH (female, medical doctor, researcher), and JF (male, medical doctor, researcher). At the start of each session, the moderators explained the procedure and aim of the focus group and informed the participants that the discussions would be audio-recorded. The moderators were allowed to rephrase comments to clarify view and notes were taken. These focus groups and the following co-construction workshop were recorded with Audacity software (version 3.4.1, free software). The medical students and the university staff members group sessions lasted 110 and 115 min, respectively (Additional files 1 & 2).

Medical students focus group

Recruitment

Undergraduate medical students enrolled in their fourth year during the 2022–2023 academic year at the Lyon-Est Faculty of Medicine (University of Lyon 1, France) were invited to participate at the conclusion of their mandatory exam in June 2023. The aims of the research project were clearly stated, and students who were willing to participate provided their email addresses. Students were contacted during the following weeks via an email notification. No exclusion criteria were applied.

Organization

The first focus group involved 11 medical students (eight females; three males; 22.5 ± 2.3 years old). Upon arrival, the participants were reminded of the study goal and informed that the data would be anonymized during the analysis. Moderators answered any questions, and the participants signed an informed consent form. All the participants completed a brief questionnaire regarding their gender and age; the results are reported in Additional file 3.

Focus group structure

The session was organized as follows (Additional file 1): First, the students introduced themselves and described their motivations for participating. They were then questioned about their needs related to health behaviors and their use of University Health Services. The students were then asked to provide their first impressions of the PROMESS project. Finally, the moderators summarized the most important ideas and explained the next steps of the project (i.e., co-construction workshop).

University staff members focus group

Recruitment

This focus group aimed to explore the experiences of university staff members involved in student health, with a particular focus on the perspectives of health professionals of the university's Health Department (University of Lyon 1, France). The goal of this department is to ensure prevention, health promotion, and care through consultations and activities. Members of the University Health Department were contacted via professional mail during June 2023. Interested members responded by mail and were later contacted. No exclusion criteria were applied. One researcher (SS), who actively works for the promotion of medical students’ health and coordinates the PROMESS program, and a graduate medical student experienced in peer coaching, were also included.

Organization

The focus group consisted of five university staff members (three females; two males; 32.4 ± 5.6): one medical doctor (the director of the University Health Department), two nurses from the University Health Department, a graduate medical student, and a researcher (SS). All the participants completed a brief demographic questionnaire regarding both individual (gender, age) and professional (level of study, profession, duration) data. These results are reported in Additional file 3.

Focus group structure

The session was organized as follows (Additional file 2): First, the professionals provided personal presentations and motivations for participation and identified the available resources for health issues at the university. Then, they identified the barriers medical students encounter when consulting the Health Department. The focus then shifted to determining the students’ needs regarding maintaining good health and performing optimally academically, with a specific emphasis on sleep, physical activity, and stress. There was a discussion on how existing tools could be improved, and the professionals were asked to provide their first impressions of the PROMESS project. Finally, the moderators summarized the most important ideas and described the upcoming co-construction workshop.

Following the focus groups sessions, a co-construction workshop was conducted to collaboratively design the PROMESS program. The medical students and university staff members involved in the focus groups were invited to participate. Ten participants (six females, four males), half of whom were medical students and half university staff members, participated in the co-construction workshop. The session lasted 180 min and was conducted at the University of Lyon 1. The same two moderators guided the session, following a predefined interview guide (Additional file 4).

The session started with a short presentation of the co-construction workshop procedure and aim. Next, all the participants introduced themselves, and the moderators provided brief feedback on the main results of the focus groups sessions. Afterwards, the moderators sought to gather impressions of the PROMESS project, with the focus on recruitment modalities, specific intervention content (i.e., module characteristics), and outcomes. The participants were then asked to discuss a list of suggestions defined by the researchers related to selfcare practices (i.e., stress, sleep, physical activity). Finally, the participants provided feedback and their level of satisfaction with the workshop was assessed.

Following the co-construction workshop, a pilot study was conducted to assess the efficacy and feasibility of the PROMESS program. Some of the medical students involved in the previous steps were invited to participate in one or two modules of the PROMESS program (stress, sleep, physical activity). They were allowed to choose the module(s) according to their needs and/or desires. Eight students (seven females; one male) participated in the pilot study. An oral debriefing was conducted immediately after the conclusion of each module. Two months later, five of these students (all females) completed a satisfaction survey (Additional file 5).

Step 1

The recordings of the focus groups were transcribed by LB. BV conducted additional listening sessions to ensure that the transcriptions were complete. To maintain accuracy and integrity, the transcripts were analyzed in their original language. The recordings of the dialogue were anonymized before analysis. LB and BV were responsible for coding the data. The analysis process commenced with familiarization with the data. Codes were developed independently by LB and BV, who then described the content. Thereafter, BV and LB discussed the codes. The codes developed independently were extremely similar; still, each one was discussed. If the verbatims were not in the same code, they were discussed again until agreement was reached on a coding framework. An additional expert in qualitative research (JF) provided advice on the coding framework to ensure consistency and to capture additional details. Inductive thematic analysis was employed with themes derived directly from the collected data. MAXQDA software was used to manage and analyze the data (Analytics Pro 2024 VERBI Software Germany). Due to logistic constraints, corrections and feedback on transcripts and research findings were not obtained from the study participants. The consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ) were applied (Additional file 6).

Step 2

The recordings of the co-construction workshop were transcribed by LB. The transcripts were analyzed in the original language. The recordings of the dialogue were anonymized before analysis. The analysis process began with familiarization with the data and consisted of detecting agreements or disagreements and extracting the most salient findings.

Step 3

The quantitative results from the survey data are presented as numbers and the extraction of the salient information.

Medical students focus group

The two moderators reported that the students felt comfortable in sharing their views and experiences, and there was no sign that they were hesitant to speak freely. A positive atmosphere of mutual respect and openness prevailed, fostering a judgment-free environment. Three overarching themes emerged from the students' feedback (Fig. 2).

Main issues and characteristics of medical students that lead to a decreased quality of life, as expressed during (A) medical students' focus group (in blue) and (B) University staff members' focus group (in green)

Theme 1: Poor health behaviors

Students reported difficulties in adopting a healthy lifestyle during their curriculum: “I used to work until 1am- 2am. In the morning I'd get up at 6am and I'd be dead tired, I'd sleep and in fact I'd live at night and sleep during the day. I really didn't have a healthy lifestyle overall.” (S1). They delved further into describing specific health behaviors such as stress, sleep, physical activity and nutrition, and explained their influences on quality of life.

Stress appeared to be an inherent part of medical students' lives, stemming from a heavy workload and the competitive nature of the exams: “Having gone through P1 [first year competitive exam], we've become accustomed to stress” (S7). “After my day, I often find myself unable to accomplish everything I had planned, leading to stress in the evening due to unfinished tasks.” (S6). Stress may impact other health behaviors such as sleep: This heightened anxiety makes it challenging to adhere to a 10 PM bedtime in order to wake up at 6 am and catch up on pending work.” (S6). While some students seemed aware of the negative influence of stress on their health, others may not fully recognize its effects: “In the context of mental health in the field of medicine, many of us are in denial.” (S11).

Many students reported sleep issues, and their sleep difficulties affected their ability to work or study: “I can't sleep until 2 or 3 o'clock in the morning. It's a vicious circle, and after a while you're neither efficient in your work nor do you get a good night's sleep. And I find it really hard to say to yourself: ok, like yes, I need to rest, so I need to get a few hours of sleep on my alarm clock in the morning, but not too much either.” (S6). Students had to continuously alternate between periods of university work and internships, which may include mandatory night shifts. This constant adjustment to their schedules led to numerous changes in their sleep patterns and could induce various sleep disorders: “Well, I know that I'm not sleeping at the moment. I'm doing 24-h shifts, I've done two in a row, I don't have any rest.” (S11). While students had difficulties taking care of their sleep, they were aware of the importance of self-care practice to manage fatigue and stress: “We have an accumulation of fatigue and other things. We never really take a break for ourselves. It's really dangerous because you end up cracking.” (S8). “I think we also have to learn to say to ourselves: there are times when our body needs a break.” (S8).

Some medical students practiced physical activity daily: “In fact, little by little I've managed to say to myself, well, I'll go to the gym at 7am and then I'll go home to work.” (S10). Other students attempted to practice physical activity but mentioned that their schedules, both related to university and internship, were not flexible enough. Even though students were aware that engaging in sports may enhance their well-being they often felt guilty about taking time for doing it: "It almost made me feel guilty to leave my desk at 5:30 PM to go to dance, even though I knew that dancing would be good for me." (S8). Additionally, they cited workload and comparison with peers as contributing factors for not practicing: “I kept seeing all my mates at work and I hadn't necessarily finished my day in my schedule, which made me feel a bit guilty, and sometimes you end up thinking, wouldn't I be better off working instead of going to the dance, when in fact it did me good.” (S8). They further declared that physical activity was the first thing they removed from their schedule when workload increased: "As soon as something gets a little difficult, it's the first thing (= physical activity) that will be removed from my schedule." (S3) and reported that performing physical activity remained a significant challenge: “In fact, if I'm not forced to take time for myself, I'm not really going to take that step ” (S6).

They also reported issues adopting healthy nutrition due to time constraints resulting from a heavy workload: "When you leave the university library at 10 PM, find a mini-market to buy something to eat…. so, that's what it was, it was sandwiches.” (S6). “I ate sandwiches.” (S1).

Theme 2: Significant environmental constraints

The students repeatedly mentioned an overwhelming workload: “I find it really hard to do everything, all the classes” (S3), and "Sometimes you have 6 h of classes, and you haven't had time to review them beforehand because you've been on an internship” (S9). The workload could lead to a loss of coherence in the course instruction: “They wanted to dispatch the classes very quickly, so they did them all, and then, well, I was there like, I didn't go to class; it's horrible” (S7).

Students described dehumanizing interactions with hospital staff, marked by a sense of disregard and a lack of empathy. This was compounded by the extensive hours spent at the hospital: “The department heads summoned us and held a meeting to reprimand us about the sick leave. Some people took leave, and they got scolded. The worst part is that we had a meeting where they told us they would invalidate our internship if we didn't show up for 24 h three times a week. We were all crying because we hadn't slept for two weeks, but they didn't care” (S11). Some of the students’ rights were disregarded: “You have to keep your mouth shut because, if you don't, there will be repercussions for your work placement” (S11). Participants criticized internship teaching methods and deplored insufficient debriefings on difficult clinical situations: “It's the first time we've seen a dead person, someone who's committed suicide. And they say everything's fine and they don't even ask us if we're alright, if we're not shocked. No, but it's true, I was shocked at the emergency room” (S9).

Students reported several issues. First, organizing schedules became a mental workload: “The classes are pretty badly organized because we don't have the schedule in advance; sometimes we don't have the rooms in advance and that takes up a lot of our energy. There were weeks where I was more exhausted from organizing my week than from working” (S3). Second, the allowance received for their internship was declared to be insufficient; this topic was frequently raised, and some students reported lacking adequate financial security to maintain decent living conditions: “I know my fridge has been empty for 2 weeks. And I steal patients' food at the hospital when I'm there. Well, whatever's in the fridge. I know that I haven't eaten or eaten badly for 2 weeks because I don't have any money” (S11).

Theme 3: Influence of personals factors

Students acknowledged that excessive work influenced their quality of life negatively, but they seemed to accept it: “I have the impression that the risk benefit is negative. It's better if I'm a bit less well mentally, but I work hard on my classes” (S6). This intense focus on their studies could lead to feelings of isolation and loneliness due to reduced time spent with family and friends: “I spend a lot of time in my notebooks, very…well…alone” (S7). Students also reported that many medical professionals believe in the necessity of suffering to succeed in medicine and transmit this mindset: “You've chosen to go to medical school, so you handle it” (S6). “We need to change the mentality in which we're told […] that you don't have time and that there's only work in your life” (S1).

The students maintained complex relationships with others, which oscillate between competition and the need for connection and understanding: “We're always imagining that other people are doing better than us” (S3). “If we don't work, we feel like we're going to miss out on things compared to others. It's still a competition, so if we work less than the person next to us, we will be less successful” (S7). Sharing challenging studies fosters a deep understanding among them and provide mutual reassurances: “We're lucky to have a class that is supportive and less competitive” (S6). They expressed a keen desire to create connections with others: “It's a good idea to try and create cohesion and make sure we can talk to each other, which isn't always easy” (S3).

Obstacles to changes

There were some barriers to changing behaviors and improving the wellbeing of students. First, the workload prevented students from freeing up time to engage in activities other than work: “In my head, I'll tell myself that it's a sort of waste of time compared to my work. I won't see any benefit for my mental health because I'm too caught up in my work” (S1). "If that time (time for her) isn't imposed, I won't take it, personally" (S6). Second, they have complicated relationships with medical staff, difficulties in communicating their limits, and a lack of social support that hampers their wellbeing.

Suggestions to improve wellbeing

The students provided numerous ideas to increase their wellbeing: improving working conditions (limiting workload or developing communication strategies before internships), improving communication and access to healthcare (health education, better access to the Health Department, psychological support), and offering more mental health prevention programs based on longitudinal monitoring. One student described her experience in another region, where a systematic follow-up with a psychologist was proposed during her first year and again later, if necessary. They wished for greater respect for their rights regarding working hours during internships and that they could learn to be more assertive: “I think that's also something that needs to be put in place, working on our mental strength, so that we know when to say ‘stop’ during an internship when I'm there for 24 h” (S1). Finally, they wanted a stronger connection with other medical students, especially outside the school: “It's a good idea to do things together but outside of school” (S10).

Understanding the use of the University Health Services

The students were familiar with the services offered by the university’s Health Department (i.e., psychologists, dieticians, nurses, or doctors). However, they explained that there were not enough appointment availabilities and that scheduling might be somewhat challenging: “I had filled out an online appointment request, and they called me back to inform me that there was a 6-month wait” (S8).

Opinions on PROMESS

The students were highly interested in the PROMESS program and expressed gratitude for the faculty's initiatives. They expressed a keen desire to actively participate in improving the mental health department offered during medical studies and fostering solidarity among fellow students: “It's certainly going to help us for the competition, but personally I'd be a bit disappointed if at the end of this study I said to myself, well, the other years are going to be the same, they're going to have just as hard as we had, there's nothing we can offer them, we're doing this so that things can get better” (S6). They agreed that other medical students may be interested in participating in the PROMESS program in the future: “With the Objective and Structured Clinical Examination, I think there are a lot of people in the class who would like to take part” (S1).

They expressed a preference for individualized interventions (i.e., one-on-one meeting): “It's easier to open up when you're on your own” (S3). While the majority of students perceived the usefulness of participating in all three modules (stress, sleep, and physical activity)—“I think the three modules complement each other” (S11), and “I really want to try out the three modules” (S10)—one student expressed some doubts about the usefulness of physical activity: “I didn't see any point in it in the sense that I know I'm sedentary; I know why I'm sedentary” (S1). They also expressed a preference for in-person sessions with an optional video alternative. Regarding interactions with experts, they felt more at ease with medical staff compared to other individuals—“I would prefer it to be someone in medicine who understands us better than a coach” (S1)—but remained open to other possibilities: “If we could have two people, maybe one in medicine and one specialist, it would really allow for both understanding and providing solutions” (S6).

University staff members focus group

The two moderators noted that all the professionals felt comfortable sharing their views and experiences. Two overarching themes emerged (Fig. 2).

Theme 1: Poor health behaviors

The university staff members reported that medical students encounter more stressful situations than other university students. Stress is relative to competitive exams and changes in the social environment: “It's true that the first year is very, very stressful and when they start the second year, three quarters of their friends haven't passed the entrance exam of the first year. So they have to make new friends, they don't know anyone. So, it's very, very stressful too. In the third year, it's generally fine, and in fourth year you start a new cycle” (P4). Students’ stress might result from actions of their peers: “We also asked them, does it stress you out to be judged negatively by your peers on your skills or knowledge? Which isn't even an exam; it's just training, and at first the vast majority said yes” (P4).

The university staff members reported that medical students experience sleep issues and fatigue due to part-time periods (i.e., alternating between academic study time for revision and hospital work time for internships) and constraints related to hospital work.

The university staff members believed that medical students do not consider physical activity to be essential for their health and performance: “You need to try to make them understand that, when others are working, you're doing sports, but at the same time, you'll be working twice as effectively as someone who didn't take a break” (P5).

The health professionals reported that students should also pay attention to other areas, such as nutrition or drug use: “There is an issue of eating disorders among students in health studies” (P1). “Like smoking a cigarette can be calming, like drinking alcohol can be calming […] It's a way to ease one's anxiety” (P5).

Theme 2: Specificity of medical students

The university staff members declared that the mentality of medical students differ from that of other students: “Well, there are definitely some profiles (laughs). Top of the class, top performer, no failure, perfectionist, that's it” (P5). They reported that medical students often compare themselves to fellow students: “When they arrive, they compare those who have been doing pre-prepared classes since July with those who are starting their year now” (P1). In addition, medical students seem more likely to not accept their weaknesses and to refrain from seeking assistance: “It was difficult for them to admit that they weren't feeling well and to go and ask for help or to take hold of things to take care of themselves because deep down they feel that "we are the strongest” " (P5). Some university staff members who are also doctors reported sharing certain characteristics with medical students that allowed them to better understand the students’ mentality: “Finally, I've been through it too (laughs); we're like rocks” (P5). “It's true that we knew [this participant was extern in this university] that there was a health service at the university. We didn't necessarily go there. You really tell yourself to go when your case is desperate” (P4).

The university staff members noted that some of the students’ issues are directly linked to the curriculum. First, they emphasized the heavy workload that prevents students from taking time out for other activities: “There's no time to devote to sport, no time to devote to wellbeing; the schedules are very full, so inevitably that's a source of unhappiness” (P5). Second, they reported that academics are also partially responsible for the medical students’ unhealthy mindset: “The problems with medicine is right from the outset, we tell them: ‘You're going to work hard, you've got to forget about you. You're going to have to tough it out and that's that’” (P1). Third, they discussed the pressure that medical students may be under due to the competitive nature of exams: “Once you have an entrance exam at the beginning and an exit exam, you're inevitably compared, which leads to a sense of devaluation that contributes to discomfort, along with doubt and self-questioning like ‘but the others…’” (P5), or “It's an exam that will decide for the rest of your life where you're going to live, what kind of job you're going to do” (P4). Finally, the university staff members reported a deterioration in medical students’ health during their curriculum.

Issues encountered by the Health Department

University staff members working in the Health Department mentioned that they have encountered difficulties in communicating with the faculty staff due to internal issues, notably with administrative staff turnover. They also mentioned that communication with students might not be optimal: “Students don't necessarily know about it (Health Department), which doesn't mean they're not informed, but it does mean that the information hasn't been given in the way they want to receive it” (P3). To enhance communication with students, professionals are considering how best and when to make students aware of the services available: “I think it might be interesting to prioritize rather than say that we'll do all the years if there's the first and fourth year, but if there are already pivotal years when we know that there are new arrivals” (P1). Finally, they noted that only a small percentage of students study on university premises, which can contribute to physical and social isolation. As a result, these students may be more susceptible to distress and poorly informed about the available services: “Those who come to university are in the minority. There are plenty of people who never come to university because the classes aren't mandatory and who work at home or in a preparatory course, and many of these people are the ones who might need it the most because they're the most isolated, but the University Health Department don't reach them because they're not physically there” (P4).

The professionals also explained that the number of staff working at the University Health Department is largely insufficient to care for all university students, which means that they are unable to devote sufficient time to medical students in particular: “But the problem is that afterwards it's always the same: we don't have the human resources…” (P1). This situation has repercussions for the health professionals: “We work a lot as a team on this thing of saying no because we find it hard and in fact we often get into trouble because we find it hard to say no to students and we don't have the resources” (P1).

Opinions on PROMESS

Regarding the PROMESS program, all the professionals believed that the program will be beneficial for medical students and thought that it was extremely important to complete all three modules: “Health is about the whole picture, and that's what we want to show them with this project, that health is about taking care of stress, sleep, and sport, so I think the intervention is really complete if they have all three modules” (P1). They further mentioned that the idea of individual sessions (i.e., one-on-one meetings) was valuable: “I think they need to be alone, they're always in a group, so I think an individual thing makes sense” (P1). Regarding the experts who would accompany the medical student during the module, they recommended that they should be a member of the medical staff, such as graduate medical students, healthcare professionals, or individuals who are familiar with the unique challenges medical students encounter. They also stressed the importance of having experts who are not directly involved in the medical curriculum, which may allow the students to express their difficulties more freely and without fear of any repercussions in a professional or academic context: “It would be good to have people from outside the curriculum who feel free to say what they want to say and express what they want to express, that's important” (P1).

The professionals also indicated that the PROMESS project may help to improve communication in Health Department. Finally, the professionals questioned the dual aspects of the program —quality of life and academic performance—: “Personally, I always have a problem when performance and wellbeing are lumped together. I think there's a dichotomy and, in this context, I think it's very appropriate, but that's not always the case” (P1), and they emphasized that, to engage medical students in the program, the researchers should emphasize the expected effects on performance: “The way to get them on board is to tell them that they'll do better in the future, but if we oppose them, they won't choose wellbeing” (P4).

The co-construction workshop with both medical students and university staff members allowed for adjustments to the PROMESS program (Fig. 3). The participants often reached agreements on decisions, and no thematic analysis was conducted as the summarized information was deemed sufficient.

Main findings of the co-construction process of the Preventive Remediation for Optimal MEdical StudentS (PROMESS) program. The findings from the workshop (Step 2) are indicated e in orange and the results of the pilot study (Step 3) in purple. These results will be incorporated into the PROMESS program to enhance the program's effectiveness and relevance for future students

The participants agreed that the PROMESS program should be offered to undergraduate medical students. They indicated that the third and fourth year students would be the most amenable to the implementation of the program, as they are not too close to the main ranking exams of the French curriculum.

The participants suggested that the project could be communicated through medical students’ associations, social media platforms, or presentations incorporated into lessons at the beginning of the year. They further estimated that approximately 10% of students would voluntarily participate in the PROMESS program.

To offer adapted advice that is best-suited to medical students, the participants suggested that the expert should be someone who is familiar with medical studies but not directly involved in their academic progression. This should ensure that the advice provided is relevant and informed, without the potential for bias or influence on the students’ academic trajectories. They proposed that the expert could be a graduated medical student, a health professional, or even a sports coach for physical activity. They believed that having two experts, one medical student and one health professional, could be beneficial. A considerable amount of time was devoted to potential mental health issues. The participants suggested that the stress expert might be a graduate student in psychiatry and that the contact details of appropriate health professionals or the University Health Department should be made available for cases of emotional distress.

The three modules appeared to be relevant and well-adapted to the students' needs. The list of advice to be provided to the students was considered to be appropriate. The participants discussed the importance of incorporating nutritional aspects into the PROMESS program. While some considered the nutritional aspect to be crucial, others viewed it as important but not essential. They agreed that the nutritional aspect could be integrated into the module on physical activity or sleep. For the physical activity module, in addition to one-on-one meetings with the expert, students requested a free weekly physical session late in the afternoon, held near the libraries and hosted by the faculty, to make it easier for them to attend after their study sessions.

The participants suggested an engagement contract: the voluntary student should sign a contract to promote their commitment and motivation. The students should specify their goals in the contract. The participants also suggested limiting the pieces of advice provided per session to five and taking into account a gradual increase in difficulty.

The participants provided their opinions on the primary outcomes of the PROMESS program. They suggested that quality of life and academic performance should be considered as primary outcomes. Self-confidence, self-esteem, and life satisfaction were regarded as fundamental indicators of quality of life. Grades, rankings, personal satisfaction, and feelings of efficiency could be used as key indicators of academic performance.

The participants were highly satisfied with the workshops. Their involvement in the PROMESS project seemed to have bolstered their motivation and inclination to change their behaviors. The participants suggested that, should a new co-construction workshop be organized, additional stakeholders, such as a sports physician and physiotherapist, should be included in the process.

Following the focus groups and the co-construction workshop, the PROMESS program was adapted, and the students were offered the opportunity to experiment with one or two modules. Each module was supervised by a graduate medical student and/or a researcher with previous experience in health professional coaching (SS; https://topsurgeons.univ-lyon1.fr/en/team/). Each module consisted of individual meetings, during which experts assessed the needs of the students through questionnaires and discussions, provided personalized advice, and set goals to help the students to adopt healthier lifestyles. These meetings were spaced approximately 7 days apart.

Eight students (seven females, one male) voluntarily tested the program and provided feedback (Fig. 3). The stress, sleep, and physical activity modules were followed by four, four, and seven students, respectively. An oral debriefing was conducted immediately at the conclusion of each module. In addition, a survey was distributed two months later to assess the medium-term satisfaction of the 8 included students; only five female students responded.

The general organization was considered to be well and very well adapted to them constraints and needs (n = 4 and n = 1, respectively). The time between sessions was considered to be adapted and well adapted to them (n = 3 and n = 2, respectively).

The students were satisfied or very satisfied (n = 1 and n = 4, respectively) with their relationships with the experts, whom they described as caring and educational. The individual support (one-on-one meeting) was greatly appreciated and considered to be necessary. The testimony of a graduate was considered essential by three of the students, who felt that they were understood; one student had no opinion, and one student felt that this testimony was not essential, as the researcher was available and understanding.

The content was considered appropriate and very well appropriate (n = 2 and n = 3, respectively). The explanations provided were clear, and the students were allowed autonomy to achieve their goals. The participants occasionally encountered barriers due to their workload but acknowledged that the guidance remained applicable during both university classes and internship periods. The students felt that the advice had a positive effect on their feelings of stress (n = 5), their sleep quality (n = 5), and the quantity/quality of their physical activity (n = 4). For the physical activity module, feedback on the 1-h sport session was highly positive.

All the students declared that they were extremely satisfied with the intervention (n = 5). They believed that the behaviors that they had adopted had become entrenched (n = 5). They also felt that the intervention could improve their quality of life (n = 5) and performance (n = 5) and would recommend the intervention to other students (n = 5). Furthermore, they suggested that the meetings should be spaced further apart to integrate the behavioral changes and improve the effectiveness of the intervention.

The participation in this study changed the perspectives of three students regarding wellbeing, as they became more aware of the consequences of neglecting their own needs. They began to prioritize aspects such as stress management, sleep, and physical activity. Conversely, two students believed that the intervention did not change their behaviors significantly, as they were already aware of the importance of wellbeing beforehand. Nevertheless, all the participants highlighted a heightened sense of awareness following the intervention. Finally, three students noted a change in other behaviors (e.g., nutrition).

The objective of the present study was to identify the health behaviors-related needs of medical students in order to design a tailored intervention. A three-step study was conducted, comprising two focus groups (with medical students and professionals from the university), a co-construction workshop, and a pilot study. Both the co-construction workshop and the pilot study facilitated the development of the multi-modal PROMESS program and enhanced the feasibility and acceptability of the program for broader implementation (e.g., individualized advice, multiple one-on-one meetings, peer coaching, completing the three modules, signing a commitment contract).

This study corroborates previous findings that medical students encounter many challenges in adopting healthy lifestyles and provides a deeper understanding of issues related to stress, sleep, and physical activity [16]. Both the students and professionals reported that medical students encounter numerous stressful situations, have high levels of stress and anxiety, and often experience a significant deterioration in mental health. Stress and anxiety among medical students are well-known problems that may manifest from the start of the curriculum and continue throughout their residency [16,17,18,19,20]. The participants also reported that medical students experience sleep disorders due to irregular schedules resulting from alternating university work and internship periods, which is consistent with previous findings [21,22,23,24]. Physical activity levels varied among the participating students, with some maintaining a regular exercise schedule, while others reported barriers to participating in sport activities. Previous findings have shown that medical students are less active than other students, especially in regards to moderate to vigorous physical activity [8, 25, 26].

Significant workload

As reported in previous research, the heavy workload and the competitive aspect of the curriculum were identified as the main barriers to wellbeing and major causes of distress [17, 27]. The workload prevents students from taking personal time and include selfcare practices in their busy schedules. For instance, the students noted that physical activity was the first to be set aside when workload increased. Previous research has reported that students often struggle to maintain regular physical activity due to time and energy constraints [28, 29]. Overall, the students stated that they prioritize their work over their wellbeing.

Guilt and peer comparison

The students reported feeling guilty when engaging in activities other than studying, which hinders the practice of selfcare. Guilt may be deeply engrained for some medical students [16, 20, 30]. Satterfield and Becerra (2010) reported that anxiety and guilt were the most prevalent emotions among medical students during postgraduate training. Our finding also showed that peers can be perceived as both a potential threat or a valued support, which leads to a mixed feelings and highlights the complex relationships among medical students. More specifically, peers can be an additional source of stress due to the inherent competitiveness of exams, leading to unhealthy comparisons. A previous study has shown that this competitive environment often causes students to undervalue their own worth and can lead to self-neglect [16]. However, our participanting students also reported a desire to engage in extracurricular activities with their peers and to receive additional support from them, particularly to address the challenges encountered during internships. Therefore, peers seem to be an important and expected source of support for medical students [20].

Medical students’ mindset

The health professionals believed that medical students’ mindsets differ from those of other students. They explained that they do not consider their physical and mental health to be a priority and disregard the fact that sleep and exercise are essential to their health and academic achievement. These considerations lead to poor health habits and quality of life. Similarly, studies have reported that some medical students deliberately allocate more time to their studies than to sleep, even when their level of fatigue is high [31, 32]. They also reported that medical students struggle to assess their needs, seek help, and accept vulnerabilities, which may result from individual characteristics and/or the culture of academic medicine. Previous research has indicated that the fear of being perceived as weak and the stigma associated with mental illness may deter students from seeking help [27]. Finally, it was noted that many medical professionals still believe that it is necessity to suffer to succeed in medicine, and they perpetuate this mindset.

Our findings confirm the difficulties medical students have to overcome to adopt healthy behaviors. Since unhealthy behaviors can cause significant deterioration in their wellbeing, quality of life, health, and performance, it is essential to provide them with support [1, 3,4,5, 10, 23, 33, 34]. To address this issue, faculty should offer solutions to limit both the occurrence and severity of issues related to unhealthy behaviors. University health department, whose primary mission is to provide support for students, are available in many countries. Locally, our students were aware of this service but criticized the insufficient availability of appointments. The professionals explained that they are understaffed and acknowledged that they are unable to provide sufficient support for medical students. These issues are not only local, as other faculties also struggle with the same issues [35]. As a deterioration in medical students’ health has been noted worldwide [18, 36,37,38], it remains necessary to provide additional services tailored to the specific needs of medical students [17, 38].

PROMESS program

In the context of providing support to medical students, the PROMESS program appears to be relevant. The students and professionals expressed a strong interest in the project, deemed it to be valuable to students, and anticipated active student engagement in the future. Kushner and collaborators described an intervention fairly similar to PROMESS [39]. In their study, medical students had to select a behavior that they would like to change (e.g., exercise, nutrition, sleep, mental health). The participants remained autonomous in setting their goals, finding solutions to achieve these goals, and assessing their own progress. Following the program, only 40.5% of the students indicated that they had achieved their goals [39]. This outcome underlines the inherent difficulty of changing health behaviors. More intensive support may be required to increase the effectiveness of such programs. Accordingly, our participants believe that expert guidance is essential and requested personalized support through multiple one-on-one sessions that offer a save space for discussions. To enhance the motivation for change, they suggested setting only a few specific goals and signing a commitment contract.

The participants provided further recommendations for the construction of the program. They all agreed that support should be provided by individuals with a good understanding of the medical curriculum and its difficulties. The final recommendation was that the experts could be more experienced peers (i.e., graduated medical students) so that the PROMESS program might become a form of peer coaching (i.e., peer monitoring). Peer coaching may offer numerous advantages for students and institutions [18, 27, 40]. Involving students in leading the sessions should enhance social support, promote positive peer comparison, foster empathy, and give students a sense of ownership over their educational experience [18, 27, 41]. From an institutional point of view, using students in the role of experts remains a cost-effective approach, which may be a key point for large-scale implementation [40]. Finally, students deemed it crucial that the experts have to be independent of the curriculum to prevent themselves from being judged. This feedback emphasizes the importance of careful consideration in the selection of individuals to conduct supportive programs for students to ensure ongoing effectiveness and credibility.

The majority of our participants also recommended that stress, sleep, and physical activity should all be addressed during the PROMESS program. While this remains to be tested, a potentializing rather than simply additive effect of the modules could be expected. Indeed, given the expected bidirectional effects of the modules—such as that lower stress levels may improve sleep and vice versa [42,43,44]—one could expect greater efficiency through a synergistic cycle. Finally, the participants stressed the importance of considering other health behavioral aspects, such as nutrition or drug use [45], and suggested that nutritional aspects could be included in the sleep or physical activity module. Both students and professionals indicated that the PROMESS program could improve the students’ quality of life and academic achievement. They agreed that markers of quality of life (self-confidence, self-esteem, and life satisfaction) and academic performance (grades, rankings, work fulfilment, and feelings of improvement) should be considered as primary outcomes.

In the final step of this study, eight students piloted the PROMESS intervention, which had had all the aforementioned recommendations incorporated, and provided direct oral feedback. In addition, five students completed a satisfaction questionnaire two months later to assess the potential long-term effects. The students consistently found the sessions to be appropriate, with clear explanations and autonomy to pursue objectives. The majority reported high satisfaction with the experts and described them as being caring and educational. Individual support was greatly appreciated. Shared themes among the participants were a heightened awareness of their behaviors, enhanced quality of life, and a belief in the enduring positive effects of the newly adopted behaviors.

This study is subject to several limitations. The small sample size may limit the generalization of our results and could have generated a selection bias (e.g., volunteers may have had a heightened interest in the themes addressed). Only five of the eight students responded to the questionnaires following the pilot study. It is plausible that those who answered were also the ones who were most satisfied. Despite these limitations, the study also possesses notable strengths. First, the study comprised three construction steps: focus groups, a co-construction workshop, and a pilot study. It is expected that this stepwise systematic approach that enabled the development of a tailored intervention would enhance its feasibility and effectiveness for a larger implementation [11]. Second, including university staff members in the development of a health program tailored for medical students is highly innovative. To the best of our knowledge, this study is the first to triangulate users (medical students) and providers’ (University Health Department members and researchers) points of views in the needs assessment and development of a health-promoting intervention.

The assessment of challenges encountered by medical students highlighted the significance of the PROMESS project. Engaging in group interviews and a co-construction workshop facilitated adjustments to the intervention to enhance its feasibility, aimed at a broader and sustainable implementation in the long term. The students expressed a strong interest in the project and were impatient to contribute to mental health research and to improve the medical studies curriculum. In addition, both the students and faculty members felt that they had been heard and understood and recognized that the initiative was urgent and necessary. Beyond the development of the intervention, this study fostered the commitment of students and university staff members. Our study emphasizes the importance of active engagement by students and universities to address health challenges in medical students.

Data is provided within the manuscript or supplementary information files.

We would like to express our gratitude to the members of the University Health Service (Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1) for their valuable participation in the discussions and their insights into the needs of medical students, as well as their understanding of the local university system. We would like to extend our gratitude to the medical interns Alexia Gleich, Olivier Loisel, and Edvard-Florentin Ndiki-Mayi, whose dedication and efforts made the pilot study possible. We would also like to thank our colleague Maxime Tête for his guidance and support.

Not applicable.

This manuscript follows the COREQ recommendation (Additional file 6).

1. A. Métais was a postdoctoral researcher at the time of the study, Research on Healthcare Performance RESHAPE, INSERM U1290, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, France; Faculté de Médecine Lyon Est, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France; and is an associate professor, Movement—Interactions—Performance (MIP, UR 4334), Nantes Université, Nantes, France. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0009 - 0006 - 0876 - 5325

2. L. Besnard is a graduate medical student, Faculté de Médecine Lyon Est, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France

3. B. Valero is an engineer, Département des Sciences Humaines et Sociales, Centre Léon Bérard, Lyon, France.

4. A. Henry is a medical doctor, the director of the University Health service of Claude Bernard University Lyon 1

5. A.M. Schott-Pethelaz is professor, Research on Healthcare Performance, RESHAPE, INSERM U1290, Université Lyon 1, Lyon, France. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000 - 0003 - 3337 - 4474

6. G. Rode is professor and dean, Faculté de Médecine Lyon Est, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, CNRS, INSERM, Centre de Recherche en Neurosciences de Lyon CRNL U1028 UMR5292, TRAJECTOIRES, F- 69500 Bron, France. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000 - 0003 - 2751 - 1217

7. J. Haesebaert is professor, Research on Healthcare Performance RESHAPE, INSERM U1290, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, France. ORCID https://orcid.org/0000 - 0001 - 9109 - 5604

8. J.B. Fassier is professor, Faculté de Médecine Lyon Sud, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France, ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000 - 0003 - 3885 - 4987

9. S. Schlatter is a postdoctoral researcher, Research on Healthcare Performance RESHAPE, INSERM U1290, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, France; Faculté de Médecine Lyon Est, Université Claude Bernard Lyon 1, Lyon, France. ORCID: https://orcid.org/0000 - 0003 - 0769 - 1521

This work has been financially supported by the contribution of student and campus life of the Claude Bernard University Lyon 1 (Grant number 22 CVEC_SAN). This funder had no role in study design, collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; decision to submit the article for publication.

All participants gave consent to participate in the study in agreement with the ethical approval of the present study (Research Ethics Committee of the College of General Medicine of the University of Lyon 1 (CUMG UCBL- 1, Lyon, France); Institutional Review Board IRB: 2023–07 - 04–04) and all the procedures have been performed in adherence to the Helsinki declaration. All participants received oral and written information, and provided a written consent prior to enrollment in the study following a sufficient reflection time.

All authors gave their consent to publish the present article.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Métais, A., Besnard, L., Valero, B. et al. Addressing medical students' health challenges: codesign and pilot testing of the Preventive Remediation for Optimal MEdical StudentS (PROMESS) program. BMC Med Educ 25, 812 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-07209-4

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-07209-4