BMC Infectious Diseases volume 25, Article number: 461 (2025) Cite this article

Peer support groups may contribute to adherence and play a role in decreasing the stigma of antiretroviral therapy (ART) adherence among young people living with HIV (YPLHIV). However, peer support activities usually occur face-to-face in Uganda and elsewhere in Sub-Saharan Africa and thus have structural limitations and may not be readily available when young people need them. Online peer support has the potential to help YPLHIV access regular psychosocial support without significant effort or cost. We assessed the acceptability of a WhatsApp peer support group as a strategy to improve ART adherence among Ugandan YPLHIV.

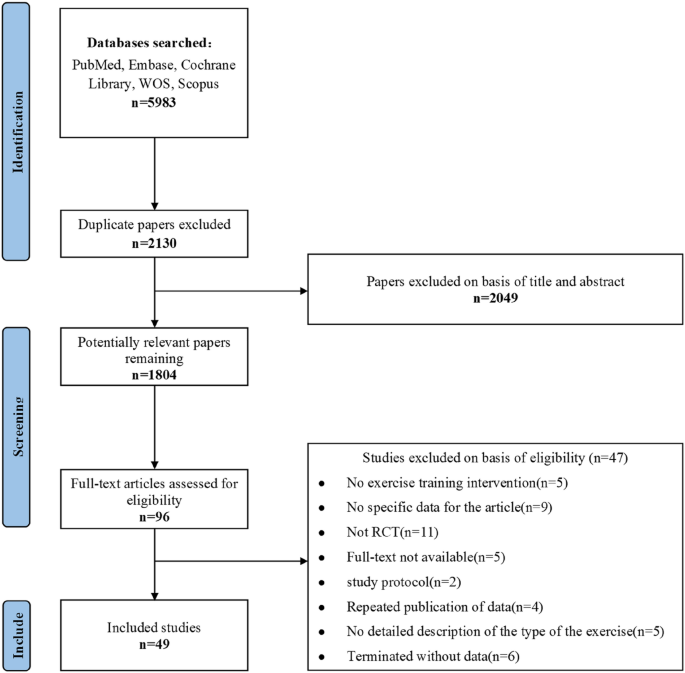

We conducted a formative qualitative study in three health facilities in Kampala, Uganda, between July and August 2022. We held four focus group discussions with twenty-six YPLHIV seeking services at the study facilities. We also conducted six key informant interviews with health providers attached to adolescent HIV care clinics. Data was analyzed using thematic analysis guided by Sekhon’s theoretical framework of acceptability (2017), which conceptualizes acceptability through multiple constructs, including affective attitudes, burden, intervention coherence, and perceived effectiveness. Our analysis examined these dimensions in the context of WhatsApp-based peer support groups for HIV care.

Overall, WhatsApp peer support groups were acceptable for use among YPLHIV. The young people regarded it as convenient because it would save time and would be more cost-effective compared to the transport costs of in-person meetings. Health providers revealed that the WhatsApp peer support group could reduce the stigma associated with community follow-up and empower YPLHIV to overcome stigma. Both young people and health providers suggested that online peer support could enhance emotional support, psychosocial well-being, and ART adherence. However, participants raised concerns about privacy and the cost of internet bundles and smartphones, especially for younger adolescents.

Online peer support groups are acceptable to Ugandan YPLHIV and hold promise in enhancing psychosocial support and improving treatment adherence in this sub-population. In implementing online support groups, due consideration should be given to software tools with high privacy standards and zero-rated data use for new apps. Research is needed to evaluate the feasibility and effectiveness of this peer support model in Uganda.

Adolescents and young people living with HIV (YPLHIV) account for 45% of new HIV infections globally, with 70% of this population residing in Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) [1]. Only 37% of YPLHIV in Sub-Saharan Africa on antiretroviral therapy (ART) have viral load suppression (VLS < 1000), which is a priority for ending the HIV/AIDS epidemic by 2030 [2]. In Uganda, only 54.7% of YPLHIV aged 15 to 24 years have VLS, which can be ascribed to virological resistance or sub-optimal adherence to ART [2]. In Uganda, 67–87% of the YPLHIV adhere to treatment, and this is lower than in older age groups [3,4,5]. The sub-optimal ART adherence among YPLHIV results from complex personal, interpersonal, and contextual challenges [6]. Among these challenges are the psychosocial barriers exacerbated by the social cognitive development changes that occur during adolescence and young adulthood [7]. Social acceptance especially from peers is more critical for young people than for any other age group [4]. However, many YPLHIV experience stigma and bullying, leading to negative self-images, low self-efficacy, anxiety, and depression [3, 6, 8,9,10,11]. YPLHIV struggling with depression are more prone to alcohol and drug abuse [12].

The World Health Organization (WHO) and Ministry Of Health Uganda (MoH) recommend peer support groups to offer psychosocial support to YPLHIV [13, 14]. However, in Uganda and most SSA countries, peer support group activities occur face-to-face and most often in health facilities [15, 16]. This approach has limitations like the need to travel, inconvenient working hours, and inadequate safe space for psychosocial services [15, 17]. Face-to-face interactions were further limited during the COVID-19 pandemic lockdowns [18]. Thus, psychosocial services may not be available when young people need them, hence the need for more real-time and widely feasible interventions. With the rapid increase in mobile phone availability in SSA, online peer support groups have the potential to help YPLHIV access regular and timely support [19]. In Uganda, 60.7% of young people own a mobile phone, and 87.9% use it for social media [20, 21]. Social media platforms permit virtual communities and can serve as a place for peer support group activities [22].

Online peer support groups in the United States of America (USA) and China have improved psychosocial outcomes [23, 24], ART adherence [25,26,27], and VLS among people living with HIV/AIDS (PLHIV) [26, 28, 29]. However, studies in Sub-Saharan Africa have provided mixed results with no effect on psychosocial outcomes [30,31,32], but also increased stigma levels [33]and no significant effect on ART adherence among YPLHIV [30, 32]. Acceptability is a necessary condition for the effectiveness of a healthcare intervention [34]. Successful design, implementation, and evaluation of a health care intervention depends on the acceptability of the intervention to both deliverers and recipients. Although a few acceptability studies in SSA have shown promising results [32, 35, 36], they were not guided by theory or theoretical frameworks. Furthermore, precisely what people find acceptable is deeply contextualized and interlinked with prevailing social and cultural norms [37]. Understanding and designing for such norms is critical to the success of online peer support groups, yet these remain unknown for YPLHIV in Uganda. Sekhon et al. 2017, defined acceptability as a multi-faceted construct that reflects the extent to which people delivering or receiving a healthcare intervention consider it to be appropriate, based on anticipated or experienced cognitive and emotional responses to the intervention [34]. Acceptability can be assessed at three levels: prospectively before intervention enrollment, concurrently while the intervention is being implemented, and retrospectively following the implementation of an intervention [34]. In this study, we applied the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability of health care interventions by Sekhon et al. 2017 [34], to prospectively explore the acceptability of using a WhatsApp peer support group as a strategy to improve ART adherence among YPLHIV in Uganda.

We conducted a formative qualitative study to explore the perspectives of study participants on the potential use of a WhatsApp peer support group as a strategy to improve ART adherence among YPLHIV.

YPLHIV will receive standard care and participate in a six-month WhatsApp peer support group. Each WhatsApp peer support group will include twenty-five YPLHIV, with a designated male and female peer counselor. We will allocate YPLHIV to a WhatsApp group depending on their age (15–18 years vs. 19–24 years) and the health facility where they seek care. In the WhatsApp group, YPLHIV will communicate individually and as a group with their peer counselors through private messages and the group chat. The group chat will enable YPLHIV to ask questions, post comments, and engage with one another at any time using text or audio messages based on their preferences. Peer counselors will respond to any post, question, or comment not addressed by group members within 24 h. They will post an inspirational message or joke to encourage participation if the group remains inactive for over three days. The study team will share weekly educational videos based on the Adolescent Treatment Literacy Guide for Support Group Settings [38] and the Uganda Ministry of Health’s HIV care guidelines [14]. The study team will use social listening, where the peer counselors will track conversations, complaints, and trends around topics on the group chat [39] to identify gaps in messaging and care concerns. These will inform the videos and discussions in the next week. The other aspect of the group is private communication as direct chats with peer counselors at least once a week. The messages will be tailored to young people’s treatment schedules, clinic appointments, and psychosocial state. However, young people can text a peer counselor whenever they wish to do so. All peer counselors will attend a weekly supervision meeting at the clinic with a designated adolescent health medical worker and a professional counselor. During these meetings, peer counselors will share updates on the study’s progress, discuss challenges encountered during implementation, and refer complex cases to the health worker for management. The WhatsApp peer support groups will prioritize privacy because of the stigma that YPLHIV face. First, the groups will be established as closed communities with access restricted to authorized participants and overseen by an administrator appointed by group members. Second, to mitigate discomfort around identity disclosure and to avoid potential comparisons to unrealistic portrayals, participants will not be required to post pictures or videos of themselves. Instead, participants will choose from a selection of avatars and metaphorical names to create anonymous profiles [25]. However, since literature shows that social media users respond to profile photos [40], participants will have the option to post their profile photos to facilitate the identification of their roles and build trust among group members [40]. Nonetheless, we shall use findings from this study to tailor the intervention to our target population.

The standard of care includes health education sessions, screening and treatment for infections, and psychosocial services. Psychosocial services offer peer support, counseling, home visits, and referrals based on individual needs. YPLHIV are evaluated for their adherence to ART and VLS. Non-suppressing young people undergo intensified adherence counseling (IAC).

The study was conducted at three health facilities in Kampala capital city. Kampala is divided into five divisions, with over 391,065 young people living in the city [41]. The literacy level among young people in Kampala is approximately 61%, and only 41.4% are employed [42]. More than half of the young people in Kampala city access the internet, 76% own cell phones, and 87.9% use their cell phones for social media [43]. Kampala has the third-highest HIV prevalence in Uganda, at 6.9%. Furthermore, 3.4% of the young population in Kampala is living with HIV, and 72% of these young people access treatment [44]. Kampala has 93 HIV care facilities, of which 23 (25%) are owned by the government, with the majority (13/23) under Kampala City Council Authority (KCCA) management [45]. We purposively selected a KCCA health facility with the highest number of YPLHIV in each of the three divisions, namely Kawaala HCIV in Lubaga Division, Komamboga HCIII in Kawempe Division, and Kiswa HCIII in Nakawa Division. The facilities serve a semi-urban population, and over 1,800 young people (15–24 years) had received ART by March 2020 [45].

We collected the data using Focus Group Discussions (FGDs) with YPLHIV and Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) with health providers.

We purposively selected health providers with expertise in providing HIV care to adolescents and young adults to participate in the key informant interviews (KIIs). We included health providers from study sites and affiliated organizations with more than one year of working experience with YPLHIV. Health providers were approached in person during clinic days to participate in the study. Six health providers attached to YPLHIV clinics at the study site took part in the KIIs, and these included two clinical officers, one nursing officer, one community liaison officer, and two counselors attached to YPLHIV clinics at the study sites. KIIs were held privately in counselors’ and clinical officers’ rooms. The principal investigator (PI) conducted all the KIIs in English with a semi-structured topic guide. The topic guide was developed by the PI and reviewed by all members of our multi-disciplinary research team including an experienced adolescent health and young adults’ specialist (SBK), a pediatric infectious disease specialist with particular interest in HIV research (PM), two epidemiologists and biostatisticians (JK and CK), and a social behavioral scientist with expertise in qualitative research (ARK). The development of the topic guide was informed by current knowledge about online peer support groups, health workers’ experiences with implementing interventions for YPLHIV, and our research questions. The topic guide was pilot-tested on an adolescent program coordinator and a medical doctor at Mulago Immune Suppression Syndrome (ISS) Clinic Kampala. The interviews lasted between 35 and 50 min and were all audio recorded.

We purposively selected twenty-six YPLHIV aged 15–24 years from clients registered in the ART clinics at the study sites to participate in focus group discussions. First, we reviewed YPLHIV records to screen for study eligibility and obtain their contact information. We included YPLHIV who knew their HIV status and were enrolled in HIV care 12 months before study entry. We excluded those in boarding schools and those enrolled in other studies. Eligible YPLHIV were invited to participate in the Focus Group Discussions (FGDS) during their clinical visits or by phone. The purposive selection also ascertained representative and collective input from participants based on their age, sex, and marital status. We held four focus group discussions, each with 6–9 participants. We grouped participants by age into two focus group discussions (FGDs) for adolescents aged 15–19 years and two FGDs for young adults aged 20–24 years. We also ensured facility representation by conducting two FGDs in Kawaala HCIV and Komamboga HCIII and one in Kiswa HCIII. Additionally, we aimed for a balanced male-to-female ratio across all FGDs and ensured that at least 45% of participants in the young adult FGDs were married. The PI conducted the FGDs privately in each ART clinic in Luganda, the most widely spoken local language in the area, using a translated discussion guide. The development of the discussion guide was similar to that described for the KII topic guide above, except that it was informed by YPLHIV attitudes towards online peer support and pilot-tested among five YPLHIV at Mulago ISS. Guides were flexible and modified as needed during the study. The discussions lasted between 58 and 80 min. At the end of every topic of discussion, the PI summarized and confirmed her interpretation of what members said. All discussions were audio recorded, and field notes were taken upon completion.

Data collection for both KIIs and FGDs was an iterative process. The PI reviewed recordings of the initial group discussions and interviews to identify gaps that needed to be filled in future discussions and interviews. Data collection stopped after four FGDs and five KIIs because no new information emerged from the interactions.

We used the theoretical framework of acceptability (TFA) of healthcare interventions [34] to guide our analysis. TFA was chosen because it defines acceptability clearly and has been used widely in HIV research [46]. TFA consists of seven constructs: affective attitude, burden, perceived effectiveness, ethicality, intervention coherence, opportunity costs, and self-efficacy [34]. Affective attitude refers to how an individual feels about the intervention. The burden includes the amount of effort required to participate in the intervention. Opportunity cost is the extent to which benefits, profits, or values one must give up to engage in the intervention. Perceived effectiveness is the extent to which the intervention is perceived to achieve its purpose. Ethicality is the extent to which the intervention aligns with the value system of the participating individual. Intervention coherence refers to the extent to which the participant understands the intervention. Finally, Self-efficacy is the participant’s self-confidence that they can perform the behaviors that are required for intervention participation [34].

Data were transcribed verbatim by a research assistant, and Luganda transcripts were translated into English. The PI proofread all transcripts, comparing them to the audio recordings before sharing them with the data analyst, a health services researcher with over 15 years of experience in qualitative research. The data analyst and PI reviewed the transcripts for completeness, formatted them, and removed any identifying details. A unique identifier was assigned to each transcript to conceal the information sources, and any text within the body of the transcripts with identifying information, like names, was removed before coding and analysis. This process was followed by developing a codebook after reading through the first two FGDs and the first three KII transcripts. An inductive approach was used to develop the codebook, deriving themes through the coding process. The PI and the data analyst independently reviewed the first three transcripts, and each developed separate codes. The PI and the data analyst met to harmonize the codebook, code definition, and structure. The harmonized codebook was then used during data coding. The codebook comprised preliminary sub-thematic areas, which were refined as other transcripts were coded and new themes identified. The PI and data analyst reviewed the coding structure for each theme and refined the codebook by comparing and categorizing emerging themes and their definitions. We followed the seven constructs of the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability of Healthcare Interventions to categorize the subthemes. To verify coding accuracy, a team member (ARK) independently reviewed the transcripts coded by the PI and data analyst toward the end of the qualitative data analysis. Coding and analysis of these data were conducted using ATLAS.ti Version 23.4.0. The study findings are reported following the consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ).

Twenty-six YPLHIV receiving care at the study sites participated in the study. The majority were aged 19 years or older (54%), with over half (58%) being female and 54% reporting being single. Most participants (57%) were employed, 35% attended school, and 58% had attained secondary-level education.

Six healthcare professionals comprising two clinical officers, one nursing officer, one community liaison officer, and two counselors, with a male-to-female ratio of 1:5, participated in the study. Four of these healthcare professionals had been working with adolescents for five or more years, and the majority (n = 4) held a Bachelor’s degree as their highest educational qualification.

The findings are presented according to Sekhon’s Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) constructs, as shown in Table 1. Sekhon’s Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) provides a structured approach to evaluating how acceptable an intervention is to stakeholders. It comprises seven key constructs: affective attitude (how individuals feel about the intervention), burden (perceived effort required), ethicality (alignment with personal values), intervention coherence (understanding of the intervention), opportunity costs (trade-offs involved), perceived effectiveness (belief in its efficacy), and self-efficacy (confidence in engaging with the intervention). These constructs help systematically assess acceptability at different implementation stages.

YPLHIV were willing to join the WhatsApp peer support groups because they perceived them as a convenient option that saved time and reduced transport costs. Young people believed that WhatsApp peer support groups were more cost-effective than in-person ones due to transportation expenses.

It helps when I do not have transport; I get one thousand shillings for internet bundles and go to the WhatsApp group. I can chat through my problem rather than getting too much money for transport. (FGD2Kawaala HCIV).

Furthermore, YPLHIV considered WhatsApp peer support acceptable because, unlike in-person meetings, it allows information to be discussed without being physically present.

Someone may not get transport, so cannot attend the in-person meetings. He/she misses the peer-to-peer educative session! With WhatsApp, I can still access the information at any time. (FGD2Kawaala HCIV).

Young people appreciated WhatsApp peer support groups for quick responses, saving them time typically spent traveling and waiting at the facility.

They ask us to come early at nine o’clock when they have organized a meeting. But on WhatsApp, I can post whatever question or concern I have in the morning, go to school, come back later in the evening, and find the advice I need. It will save us a lot of time. (FGD2Kawaala HCIV).

Clinicians agreed that using a WhatsApp group is a convenient way to offer support to young people.

It does not need someone to walk from home to the facility it saves transport. It saves time and someone is free to express herself or himself. So, it will help these young people a lot…. (KI Kiswa HCIII).

Clinicians and counselors endorsed WhatsApp peer support groups because they perceived them as a potentially effective communication platform for and among young people. They highlighted several reasons for their potential effectiveness, including their availability when young people need to communicate and the ability to facilitate both personalized and group communication for addressing specific concerns.

…the assurance that I have someone I can contact in case I am having an issue. I can inbox my issue privately if I don’t want to share it with the group, and I can get a quick response… (KI Komamboga HCIII).

The study participants were optimistic about the effectiveness of WhatsApp peer support groups in providing social support and improving adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). However, each group reported unique benefits from this mode of peer support. Young people considered WhatsApp peer support groups as a readily available source of social support, particularly for receiving both informational and emotional support.

When we have our WhatsApp group as young people in Komamboga. We will find time to talk. We will teach each other some things… (FGD1 Komamboga HCIII).

Young people perceived the WhatsApp peer support group as a safe space for sharing challenges and receiving support.

We have hurting experiences, but we cannot share them with people who do not know our HIV status. When you have people who know your situation, you can share it with them and they find a solution. (FGD1 Komamboga HCIII).

Young people reported that this support might reduce feelings of isolation and worry, thus improving their psychosocial well-being.

It will help us encourage ourselves and not to worry a lot… To stop worrying, some commit suicide when they feel alone. With the WhatsApp group, young people will be encouraged knowing there are people who care. So, they may not have suicidal ideations. (FGD2Kawaala HCIV).

In addition, young people acknowledged that virtual support groups were a suitable form of emotional support when in-person meetings are restricted.

WhatsApp group is a good idea; you may have a challenge but have no one to talk to at home. Yet with the WhatsApp group, you can share with members and get advice. (FGD1 Komamboga HCIII).

Young people reported that the readily available emotional support on the WhatsApp peer support group could improve ART adherence.

We will encourage ourselves to take drugs and good care of ourselves. (FGD1Kawaala HCIV).

Counselors and clinicians had similar opinions; counselors suggested that virtual support groups could motivate young people to adhere to treatment.

I think the WhatsApp group can motivate YPLHIV to take their drugs; it can help us achieve our goal of encouraging them to adhere to treatment. (KI Komamboga HCIII).

In addition, clinicians considered the WhatsApp peer support group a better intervention for improving ART adherence among young people because it encourages freedom of expression.

I believe it’s a better intervention in improving adherence among young people since they are free to express their feelings on WhatsApp. So, I believe it’s going to work. (KI Kiswa HCIII).

Counselors saw freedom of expression as an important condition in empowering young people with the knowledge needed for ART adherence.

I think it will empower them with knowledge because they will freely discuss several topics, and if they know, it will improve adherence. (KI Kawaala HCIV).

Similarly, counselors believed that WhatsApp peer support groups could provide young people with adherence reminders in a less stigmatizing manner, potentially improving ART adherence.

…young people will open their WhatsApp, and the messages will remind them to take their medicine. And there is that confidentiality where someone is not going to say, eh!…. please, when are taking your medicine? (KI Komamboga HCIII).

Counselors acknowledged that WhatsApp peer support groups could empower young people to overcome stigma.

It will empower them to fight against stigma, they will learn from one another as they are chatting. (KI Kawaala HCIV).

In addition, virtual support could reduce the stigma associated with community visits, Uganda’s current approach for following up young people with adherence challenges.

It reduces the level of stigma because when you send teams to look for young people who miss their clinical appointment or are non-suppressing. The teams have to introduce themselves… I am so and so.….I am looking for Jane because she is our client. When you send a WhatsApp message, no one will know, and the young person will not be stigmatized. (KI Komamboga HCIII).

However, one counselor was of the view that WhatsApp peer support groups may not be effective in providing psychosocial support and improving ART adherence, given that not all young people can afford the internet bundles and smartphones required to take part in the WhatsApp peer support group.

If a counselor is online, what are the chances that he/she will find everyone on the platform at the time of discussion? You might find that someone is offline because either they don’t have internet bundles or they don’t own the phone. (KI Komamboga HCIII).

The cost of internet bundles emerged as a major concern, with young people expressing fears that limited internet access could hinder their ability to participate in WhatsApp peer support groups and share their challenges.

Someone might have a problem when he/she does not have money for internet bundles (FGD1 Komamboga HCIII).

Clinicians and counselors had similar concerns that some young people may not consistently access the WhatsApp peer support groups because of the high cost of internet bundles.

The challenge is that some young people may not be online because they have to depend on their parents for internet bundles. (KI Kiswa HCIII).

Young people further highlighted the fact that smartphones needed for WhatsApp peer support groups are expensive.

The biggest challenge is that some of us don’t own smartphones. (FGD2 Komamboga HCIII).

To overcome this challenge, some young people suggested sharing phones with their parents. However, the process of accessing parents’ smartphones might be lengthy and frustrating.

If you don’t have a phone, you can use your parents’ phone, if they know your status. If you have not disclosed, you look for ways of getting one. (FGD2Kawaala HCIV).

…you may fear asking for it when he /she is using it for business, and then you claim you want to chat with the group. (FGD Kawaala HCIV).

So, adolescents are less likely to participate in WhatsApp peer support group discussions since they have to seek permission from their parents/guardians and might access their phones for limited hours.

For an adolescent who doesn’t own a smartphone, it will be very difficult for them to be active. (FGD1 Kawaala HCIV)

Counselors and clinicians agreed that young adults could afford the smartphones needed for WhatsApp, but not adolescents.

The age bracket of 20–24 most of them have smartphones. The only limitation is that adolescents may not afford smartphones. (KI Kiswa HCIII).

Nonetheless, counselors perceived WhatsApp peer support groups as a more cost-effective approach for following up with YPLHIV compared to traditional face-to-face approaches.

With WhatsApp, you will send a message, and the young person will read it. I think it’s easier than sending someone because community follow-ups are expensive. I think they cost 120,000 Ushs per week, and the risks associated with community follow-ups are very high. (KI Komamboga HCIII).

Study participants discussed the trade-offs young people must make to engage in WhatsApp peer support groups. A common concern among young people, counselors, and clinicians was the risk of confidentiality breaches. They worried that third parties could access sensitive information due to phone sharing or unrestricted access to group content. This risk was perceived to be higher among young people who share phones with siblings or other adults. This is what the participants had to say: -

This is what I was thinking about the breach of confidentiality where maybe certain discussions are accessed by non-group members. (KI Kawaala HCI V).

Some of us share our phones, now someone may request for your phone and he/she reads your chats! (FGD1 Komamboga HCIV).

So young people recommended restrictive patterns, codes, or thumbprints to limit unauthorized phone and WhatsApp users.

We can protect our phones by limiting access, and adding a password to the phone and group itself that no one knows. (FGD1 Komamboga HCIII).

Health providers identified cyberbullying as an issue with the WhatsApp peer support groups that needed to be dealt with.

Then this issue of bullying; Someone might say something that negatively affects another young person. (KI Komamboga HCIII).

However, young people did not perceive potential bullying as a challenge of the WhatsApp peer support group.

We need the WhatsApp peer support group. We cannot abandon it because of bullies. We have bullies at school, but you do not quit because of a bully! (FGD1Kawaala HCIV).

Regarding the suitability of WhatsApp peer support groups for YPLHIV value systems, participants raised concerns about equity, literacy requirements, and moral considerations. Healthcare providers, in particular, worried about the potential for romantic relationships to develop within the groups. This is what a counselor had to say; -

Young people want to explore. They can catch up and engage in relationships (KI Kawaala HCIV).

A similar observation was highlighted by some young people who had mixed sentiments to unsolicited romantic relationships. They recommended the development and implementation of standards of behavior for group members, which included no tolerance for coupling among group members.

No ‘coupling’, those in love, should express their feelings privately, but not in the group. Couples should be dismissed from the group. (FGD1 Komamboga HCIII).

A few young people mentioned that parents may hesitate to provide mobile phones to their children to join the WhatsApp peer support group due to concerns about accessing pornographic content.

…. when you talk about the phone,… He/she thinks you are going to watch pornography. (FGD1 Kawaala HCIV ).

All participants were concerned that WhatsApp peer support groups would exclude young people who could not afford or access a smartphone and those in boarding school. Below are some of the voice excerpts from the participants:

It is good, but then what about those who don’t have smartphones? Won’t they miss out? (FGD2 Kawaala HCIV).

You did not think about adolescents in boarding schools… (KI Kiswa HCIII).

One clinician noted that young people who cannot afford smartphones often exhibit more severe psychosocial needs. This clinician had this to say:

You will exclude children from my experience who are depressed, non-suppressing, and abused. They are the ones who cannot access social media. (KI Kiswa HCIII).

Counselors mentioned that WhatsApp peer support groups require literacy skills, which might be limited among young people.

It requires you to know how to read for you to understand the discussions. You can use Luganda for easy interpretation but still, some young people may not understand the information… (KI Komamboga HCIII).

During discussions, young individuals agreed that some of their peers lacked typing skills and suggested using audio messages to encourage their participation in the intervention.

…. if you don’t know how to type, you don’t know English, you may use Luganda.…, I think you may use audio messages (FGD2 Kawaala HCIV).

Nonetheless, the intervention was considered suitable for the lifestyles of young individuals who have embraced social media. Healthcare providers noted that young people were more likely to benefit from the WhatsApp peer support group due to their heavy social media use and the platform’s advantages, such as the freedom to express themselves and share concerns they might not bring up in person. Here is what some of the participants had to say:

It’s good it will help those who can access social media because young people love WhatsApp. When they are discussing with fellow young people, they open up more than with health workers or parents. (KI Kiswa HCIII).

I will get to know the individual issues young people have. challenges they face but are not free to share in face-to-face sessions. (KI Komamboga HCIII).

Young people and counselors perceived organizing virtual meetings as easy and convenient compared to physical meetings. Young people had this to say:

“It is difficult to get transport of 25000/= to reach here. However, with WhatsApp, we can suggest a day when we meet to discuss it makes life easier.” (FGD2 Komamboga HCIII).

Participants demonstrated a clear understanding of how the intervention would work, relating it to their existing experience with WhatsApp groups.

It’s something new, but I think young people will easily take it up because they know the technology. Most young people use WhatsApp, they are in several WhatsApp groups and probably some of those groups are not as beneficial as this one. (KI Kawaala HCIV)

I think you can easily get information on facility activities. They can post, for example, on Saturday we have a youth meeting. You just read the message and get the information. (FGD2 Komamboga HCIII).

The research findings showed that both YPLHIV and health providers in Uganda perceived WhatsApp peer support groups as acceptable and beneficial. They valued how easy and convenient it is to communicate on this platform, which could offer immediate emotional support to YPLHIV, leading to improved psychosocial well-being and ART adherence. Health providers further revealed that the WhatsApp peer support group could reduce the stigma associated with community follow-up for non-adhering YPLHIV and empower them to overcome stigma. However, both young people and health providers were concerned about potential breaches of confidentiality and the cost of smartphones and internet bundles, especially for the younger age group. Health providers further expressed concerns about the potential for online bullying and escalated romantic relationships through WhatsApp peer support groups. However, young people had mixed sentiments about unsolicited romantic relationships and did not consider cyberbullying a challenge for online peer support.

Consistent with findings reported by other studies in Sub-Saharan Africa online peer support groups are acceptable among YPLHIV in Uganda [32, 35, 36]. A study in Nigeria have showed that YPLHIV prefer online peer groups over in-person meetings [35]. At the same time, research in South Africa and Kenya demonstrates a particularly strong reception for interventions using popular social media platforms like WhatsApp compared to custom web-based solutions [32, 36].The acceptability of the WhatsApp peer support group was attributed to several factors, with convenience being the most notable. These findings align with previous research highlighting the potential of online peer support groups to provide psychosocial support while overcoming barriers of time and location of service [47, 48]. Thus, WhatsApp peer support groups could be used to provide immediate and accessible psychosocial services to YPLHIV. Given the acceptance of online peer support groups and the growing access to social media, it is worth exploring their feasibility and effectiveness for YPLHIV in Uganda and other Sub-Saharan countries.

However, there were several concerns associated with online peer support groups for psychosocial support and ART adherence among YPLHIV. Both young people and healthcare professionals expressed concerns about privacy and anonymity when sharing sensitive information, particularly the risk of confidentiality breaches if a third party accessed a member’s phone. These concerns echo findings from multiple studies examining social media-based support platforms [47, 48]. While custom software development could enhance privacy and anonymity protections, this would require additional resources for development and maintenance. Cost barriers may also pose significant implementation challenges, particularly smartphone affordability and internet bundle expenses for younger participants. Despite these costs, participants generally viewed online peer support groups as more cost-effective than in-person meetings. Additional concerns included the risks of online bullying and unsolicited romantic relationships, though YPLHIV had mixed views on these issues. Similar challenges were noted in a review by Crowley et al. 2023, on technology-based health interventions for HIV-positive adolescents in low- and middle-income countries [48]. Our findings highlight areas of caution and key considerations for the implementation and future scale-up of online peer support groups. Successful implementation of online peer support groups for psychosocial support and ART adherence among YPLHIV may require developing mobile apps that prioritize privacy, anonymity, and zero-rated data to ensure affordability and accessibility.

The results of this study highlight the psychosocial benefits of online peer support groups to YPLHIV. Young people perceived WhatsApp peer support groups as an easy and accessible way to receive social and emotional support. They appreciated the opportunity to connect, share their struggles, and encourage one another in a safe space, which they believed would reduce loneliness and improve emotional well-being. Studies conducted in Sub-Saharan Africa confirm online peer support groups can benefit YPLHIV in many ways, such as sharing knowledge and experiences, connection, and emotional support [35, 36] which are linked to positive psychosocial outcomes [49]. These groups promote acceptance, a sense of normalcy, and reduced isolation [35, 36], which can significantly improve emotional well-being [49]. Online peer support groups can offer several psychosocial benefits to YPLHIV. So, public health practitioners could consider adopting online peer support groups to optimize social support for YPLHIV in Sub-Saharan Africa.

Regarding stigma, our findings suggest that WhatsApp peer support groups could reduce the stigma associated with community follow-up and empower YPLHIV to overcome stigma-related challenges. This aligns with U.S.-based research showing how online peer support groups empower PLHIV to reject stigma and isolation by fostering positive self-images and supportive relationships [50]. Similar benefits have been observed among lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and queer individuals with HIV who found social support through online platforms when stigma prevented in-person help-seeking [51]. On the contrary, in Kenya, Ashely et al. 2022, found that stigma levels increased among adolescents living with HIV as group discussions encouraged participants to acknowledge and share stigmatizing attitudes, beliefs, and experiences [33]. In Nigeria, no significant differences in HIV-related stigma were observed among YPLHIV enrolled in an online peer support group [30]. These contradictory findings may reflect methodological limitations in existing research, particularly small sample sizes in pilot studies [30, 33]. Larger randomized controlled trials are needed to establish effectiveness.

The study results suggest that WhatsApp peer support groups could improve ART adherence among YPLHIV through a multifaceted approach incorporating emotional support, stigma-free reminders, and knowledge empowerment. This approach aligns with documented YPLHIV preferences for mobile health interventions that provide credible information, adherence reminders, and connections to providers and peers [22]. Studies conducted in the USA and China found that. online peer support groups that used a multifaceted approach improved ART adherence [25, 27, 52]. However, evidence on online peer support groups for improving ART adherence in Sub-Saharan Africa is inconclusive due to small sample sizes and short follow-up periods [30, 32]. Therefore, it is yet to be determined whether online peer support groups can effectively improve ART adherence for this population.

This study has several strengths; first, using the theoretical framework of acceptability facilitated a systematic inquiry, which is vital at this stage of planning implementation. With the TFA, we could examine all aspects that might hinder the use of the WhatsApp peer support group. Our study explored the acceptability of a WhatsApp peer support group among YPLHIV and adolescent health providers who had not yet incorporated it into their regular practice. With this approach, the study generated feedback that can be used to address challenges ahead of time to improve the implementation and clinical outcomes of the intervention. Finally, we comprehensively understood the acceptability of a WhatsApp peer support group and triangulated study findings from FGDs with those from KIIs. These findings were consistent, indicating that online peer support groups are acceptable in actual settings.

Despite its strengths, this study had several limitations. While the Theoretical Framework of Acceptability (TFA) informed the analysis and presentation of findings, it was not utilized in the design of the topic guides. Consequently, this may have limited the systematic generation of knowledge about the intervention. Additionally, the lead Principal Investigator (PI) designed the qualitative data collection tools and conducted all the Key Informant Interviews (KIIs) and Focus Group Discussions (FGDs). This dual role may have introduced challenges in maintaining objectivity, potentially reflecting an insider position [53]. However, to mitigate reflexivity bias, several strategies were employed, including data triangulation, incorporating the perspectives of a diverse group of adolescents, young people, and healthcare providers (clinicians, nurses, counselors, and community workers), and conducting team-based data analysis, as detailed in the methods Sect. [53]. A further limitation was the exclusion of parents and peer counselors, whose perspectives could have enriched the findings. Nonetheless, the consistent acceptability of the intervention reported by both young people and healthcare providers suggests the robustness of our results. It is important to note that our findings reflect prospective acceptability, which is assessed before the intervention’s implementation. Perceptions may shift when evaluated during or after implementation. Finally, the study was conducted in three urban healthcare facilities, which may limit the generalizability of the findings to urban contexts.

The findings of this qualitative study suggest that online peer support groups are acceptable to YPLHIV in Kampala, Uganda. These groups, facilitated through social media platforms, were identified by participants as having the potential to offer valuable psychosocial support and promote adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART). However, participants expressed concerns about issues related to confidentiality and the financial burden associated with internet access. These concerns highlight the need for implementation strategies that prioritize the development of digital platforms with enhanced privacy safeguards and zero-rated data usage to ensure equitable access. Given the perceived benefits of online peer support groups, further research is needed to explore their feasibility and effectiveness in fostering improved ART adherence and addressing the psychosocial needs of YPLHIV in this context.

Data generated and analysed during this study are not publicly available due to potential breach of confidentiality, but are available through School of Medicine higher degrees research ethics committee at Makerere University College of Health Sciences via email ([email protected] ) on reasonable request. The data obtained is in the form of audio recordings and verbatim transcripts, which are very difficult to remove all personal identifiers.

- AIDS:

-

Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

- ART:

-

Antiretroviral therapy

- FGDs:

-

Focus Group Discussions

- HIV:

-

Human Immunodeficiency virus

- MoH:

-

Ministry of Health Uganda

- PLHIV:

-

People Living with HIV/AIDS

- TFA:

-

Theoretical Framework of Acceptability

- UNAIDS:

-

The Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS

- VLS:

-

Viral Load Suppression

- WHO:

-

World Health Organisation

- YPLHIV:

-

Young People Living With HIV/AIDS

We appreciate the support rendered by Kampala Capital City Authority and thank the management and staff of the study sites. We thank all the participants in this study, and the Makerere University Behavioral Social Science program and Makerere University Research and Innovation fund for the opportunity to contribute to the knowledge in this field.

Fogarty International Center (FIC), National Institute of Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA), National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH), of the National Institutes of Health (NIH) under Award Number D43 TW011304. provided part of the funding. The study was also funded by the government of Uganda under the Research and Innovations Fund (RIF) at Makerere University. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health and the government of Uganda.

Written informed consent was obtained from healthcare providers, young adults, and caregivers of adolescents to participate in the study. Adolescents provided written informed assent after their caregivers had given consent. The consenting and assent activities were conducted separately for the adolescents and caregivers to avoid potential coercion. Before conducting any focus group discussion or interview, we sought informed oral consent to record and make field notes. Study procedures were approved by the Makerere University School of Medicine Research and Ethics Committee (IRB #2021,048) and Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (SIR170ES). Data were collected in accordance with international conventions and guidelines on research involving human subjects such as the declaration of Helsinki.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Kiirya, Y., Kitaka, S., Kalyango, J. et al. Acceptability of an online peer support group as a strategy to improve antiretroviral therapy adherence among young people in Kampala district, Uganda: qualitative findings. BMC Infect Dis 25, 461 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-025-10831-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12879-025-10831-8