What the contents of a book on JFK in 1983 said about JB Danquah being linked to the CIA

Many accounts of what role JB Danquah played with the CIA exist

Joseph Boakye Danquah (JB Danquah) was not only a national hero to some people in Ghana, he has also been controversially linked to the job of a spy before.

This contentious subject was actually the focus of a heated time on the floor of the current 9th Parliament when the members of the New Patriotic Party (NPP) decided to eulogise the Ghanaian politician and former statesman.

From the usual public statements on the man, it led to counter commentaries from the National Democratic Congress (NDC) side, particularly with regards his supposed linkages to the CIA in the United States of America.

In the aftermath of the parliamentary debates on the matter, which led to some unidentified voice calling the Member of Parliament of Klottey Korle, Zanetor Agyeman-Rawlings, the ‘daughter of a murderer.’

Following this rather worrying period in Parliament, a leading member of the NPP, Gabby Asare Otchere-Darko, made a public post, defending JB Danquah and questioning where people got the impression that he was at a time a CIA spy.

Quoting a 1983 book authored by Richard Mahoney, titled ‘JFK: Ordeal in Africa,’ Gabby shot down the claims that JB worked for the CIA.

But what are he contents of that book referenced above and what did it actually say about the linkages between JB Danquah and the work of the CIA?

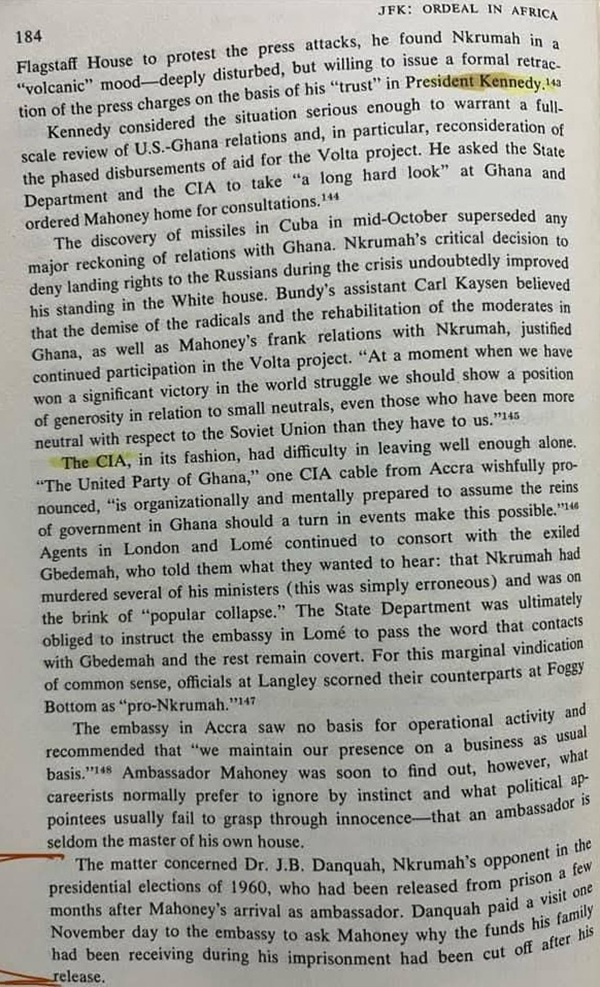

Images of the book, capturing pages 184 and 185, states, in part, “The matter concerned Dr. J.B. Danquah, Nkrumah’s opponent in the presidential elections of 1960, who had been released from prison a few months after Mahoney’s arrival as ambassador. Danquah paid a visit one November day to the embassy to ask Mahoney why the funds his family had been receiving during his imprisonment had been cut off after his release.”

Read the full extract from those pages of the book below:

184 JFK: ORDEAL IN AFRICA

Flagstaff House to protest the press attacks, he found Nkrumah in a “volcanic” mood—deeply disturbed, but willing to issue a formal retraction of the press charges on the basis of his “trust” in President Kennedy.

Kennedy considered the situation serious enough to warrant a full-scale review of U.S.-Ghana relations and, in particular, reconsideration of the phased disbursements of aid for the Volta project. He asked the State Department and the CIA to take “a long hard look” at Ghana and ordered Mahoney home for consultations.

The discovery of missiles in Cuba in mid-October superseded any major reckoning of relations with Ghana. Nkrumah’s critical decision to deny landing rights to the Russians during the crisis undoubtedly improved his standing in the White House. Bundy’s assistant Carl Kaysen believed that the demise of the radicals and the rehabilitation of the moderates in Ghana, as well as Mahoney’s frank relations with Nkrumah, justified continued participation in the Volta project. “At a moment when we have won a significant victory in the world struggle we should show a position of generosity in relation to small neutrals, even those who have been more neutral with respect to the Soviet Union than they have to us.”

The CIA, in its fashion, had difficulty in leaving well enough alone. “The United Party of Ghana,” one CIA cable from Accra wishfully pronounced, “is organizationally and mentally prepared to assume the reins of government in Ghana should a turn in events make this possible.” Agents in London and Lomé continued to consort with the exiled Gbedemah, who told them what they wanted to hear: that Nkrumah had murdered several of his ministers (this was simply erroneous) and was on the brink of “popular collapse.” The State Department was ultimately obliged to instruct the embassy in Lomé to pass the word that contacts with Gbedemah and the rest remain covert. For this marginal vindication of common sense, officials at Langley scorned their counterparts at Foggy Bottom as “pro-Nkrumah.”

The embassy in Accra saw no basis for operational activity and recommended that “we maintain our presence on a business as usual basis.” Ambassador Mahoney was soon to find out, however, what careerists normally prefer to ignore by instinct and what political appointees usually fail to grasp through innocence—that an ambassador is seldom the master of his own house.

The matter concerned Dr. J.B. Danquah, Nkrumah’s opponent in the presidential elections of 1960, who had been released from prison a few months after Mahoney’s arrival as ambassador. Danquah paid a visit one November day to the embassy to ask Mahoney why the funds his family had been receiving during his imprisonment had been cut off after his release.

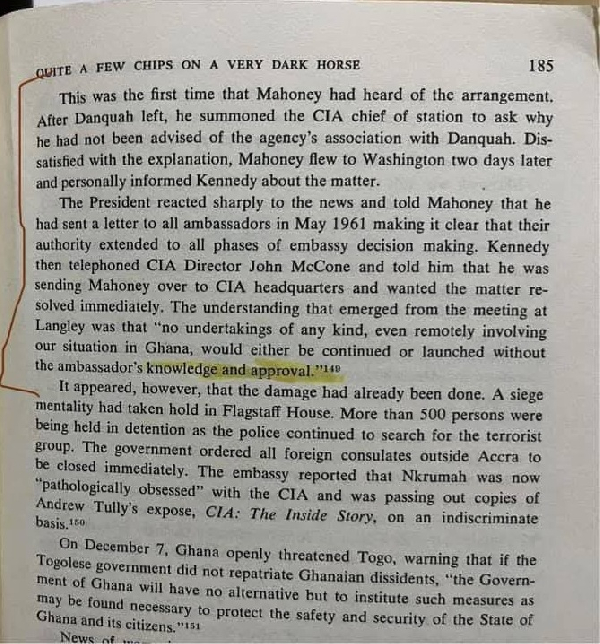

This was the first time that Mahoney had heard of the arrangement. After Danquah left, he summoned the CIA chief of station to ask why he had not been advised of the agency's association with Danquah. Dissatisfied with the explanation, Mahoney flew to Washington two days later and personally informed Kennedy about the matter.

The President reacted sharply to the news and told Mahoney that he had sent a letter to all ambassadors in May 1961 making it clear that their authority extended to all phases of embassy decision making. Kennedy then telephoned CIA Director John McCone and told him that he was sending Mahoney over to CIA headquarters and wanted the matter resolved immediately. The understanding that emerged from the meeting at Langley was that "no undertakings of any kind, even remotely involving our situation in Ghana, would either be continued or launched without the ambassador's knowledge and approval."

It appeared, however, that the damage had already been done. A siege mentality had taken hold in Flagstaff House. More than 500 persons were being held in detention as the police continued to search for the terrorist group. The government ordered all foreign consulates outside Accra to be closed immediately. The embassy reported that Nkrumah was now "pathologically obsessed" with the CIA and was passing out copies of Andrew Tully's expose, CIA: The Inside Story, on an indiscriminate basis.

On December 7, Ghana openly threatened Togo, warning that if the Togolese government did not repatriate Ghanaian dissidents, "the Government of Ghana will have no alternative but to institute such measures as may be found necessary to protect the safety and security of the State of Ghana and its citizens."

AE