A major shift in food regulation is coming. The Non-GMO Project has announced the introduction of a label for foods without ultra-processed ingredients. Meanwhile, the FDA has proposed mandating standardised front-of-pack (FOP) nutrition labelling that calls out saturated fat, sodium and added sugars.

The Non-GMO Project has announced a new Non-UPF Verified certification, rolling out as a pilot in spring 2025. This initiative will help consumers differentiate between ultra-processed and minimally processed foods, much like the Non-GMO label influenced purchasing habits. The goal? To reshape consumer choices and encourage healthier eating.

Research links ultra-processed foods (UPFs) to serious health concerns, including depression, disrupted sleep, hormonal imbalances and increased risks of heart disease, obesity, diabetes and cancer. According to the Non-GMO Project’s 2024 research with Linkage, 85% of shoppers want to avoid UPFs.

However, research from Innova Market Insights shows consumers do not have a precise definition of what they consider ultra-processed food, with 44% limiting their perception to fast food.

“Even the most informed consumers struggle to identify ultra-processed foods consistently,” said Megan Westgate, founder and CEO of the Non-GMO Project and the Food Integrity Collective. “When we tackled GMOs in 2007, we saw that genetic engineering was just one way industrial food production distanced us from natural ingredients. Today’s ultra-processed foods take that even further, transforming familiar ingredients so much that our bodies no longer recognise them as food.”

Building on this concern, California Governor Gavin Newsom’s January 3 executive order directs state agencies to explore actions to mitigate the harms associated with UPFs. His order defines UPFs as “industrial formulations of chemically modified substances extracted from foods, along with additives to enhance taste, texture, appearance and durability, with minimal to no inclusion of whole foods”.

Meanwhile, the FDA has proposed a new front-of-package (FOP) nutrition labelling system, categorising the per-serving percent Daily Value (DV) of saturated fat, sodium and added sugars. These nutrients will be labelled as Low (5% DV or less), Medium (6% to 19% DV) or High (20% DV or more). The label will also include a reference to ‘FDA.gov’ to bolster consumer trust and credibility.

If approved, large manufacturers will have three years to comply, while smaller businesses will receive an additional year. Calories won’t be mandatory on the label, though companies can opt to include them under existing FDA regulations.

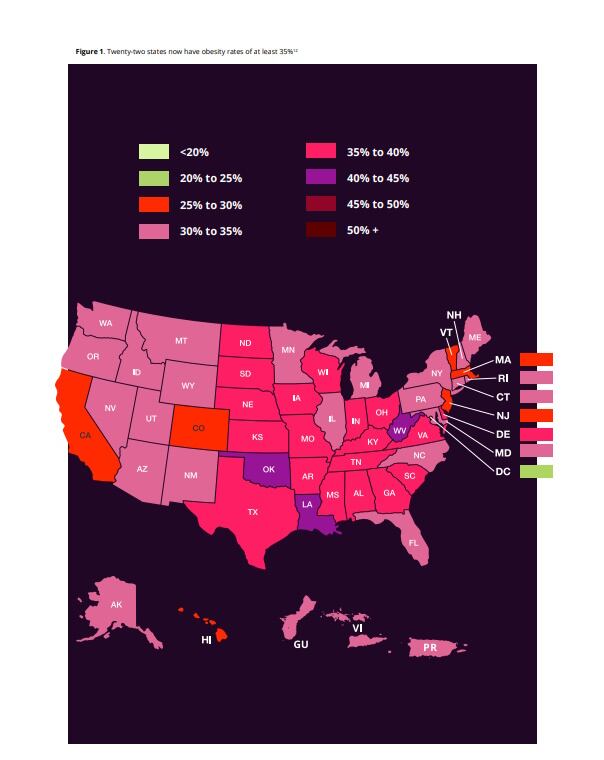

Globally, FOP labelling has gained traction, with mixed results. Countries like Chile and Mexico have implemented aggressive warning labels, leading to a decline in sales of high-sugar, high-sodium and high-fat foods.

In Chile, sales of sugary drinks fell by 23% within the first year of implementation. However, obesity rates have continued to rise, suggesting a possible substitution effect. On the other hand, Canada’s Health Star Rating system has had a more limited impact, with studies showing minimal shifts in consumer purchasing patterns. In the UK, the traffic light system has shown some success in encouraging healthier choices, but long-term effects on obesity rates remain unclear.

While FOP labelling may help some consumers make healthier choices, evidence suggests that it’s not a silver bullet for reducing obesity rates. Policymakers may need to consider complementary strategies, such as education campaigns and reformulation incentives, to achieve meaningful public health outcomes.

The war on UPFs is escalating, with food companies facing increasing legal scrutiny over their products’ addictive qualities and potential health impacts.

In December, law firm Morgan & Morgan filed a lawsuit in the Philadelphia Court of Common Pleas against 11 majors, including Mondelez, Kellanova, Nestlé, Kraft Heinz and Coca-Cola. The suit alleges these corporations intentionally designed and marketed UPFs to be addictive, leading to a rise in chronic illnesses like diabetes and heart disease. The plaintiff, Bryce Martinez, claims he developed type 2 diabetes and fatty liver disease by age 16 due to consuming these products.

The lawsuit draws direct parallels to the tobacco industry, arguing that food companies used a “1980s cigarette playbook” to hook consumers, particularly children. Historical references in the filing suggest that Big Tobacco leveraged its expertise in addiction science when it acquired major food brands. If successful, this case could set a precedent for future litigation against the UPF industry.

Separately, law firm Hilliard Law is gathering plaintiffs for a potential lawsuit against the FDA. Rather than targeting manufacturers, this case focuses on the GRAS (Generally Recognised as Safe) designation, which allows companies to self-certify novel additives without requiring FDA approval. The firm argues the FDA has failed to properly regulate these substances, harming public health.

Across the Atlantic, the UK’s House of Lords Food, Diet and Obesity Committee released its Recipe for Health report in October, advocating for mandatory health targets to reduce fat, salt and sugar in processed foods. Recommendations include expanding reformulation programmes, imposing additional health taxes and holding the food industry accountable for its role in the obesity crisis. The UK government has committed to developing a National Food Strategy in 2025, with a focus on food security, health, the environment and the economy.

Also read → Should bread be tarnished with the derogatory UPF brush?Back in the US, Mass General Brigham in Boston has launched Truefoods.com, a free database that helps consumers identify and avoid UPFs. Developed by researchers using advanced algorithms, the database assigns a processing score to over 50,000 food items from major grocery retailers like Target, Whole Foods and Walmart. The initiative aims to simplify healthy eating decisions by providing transparency on food processing levels.

And there’s more.

The movement against UPFs is expected to gain further traction with Robert F Kennedy Jr’s appointment as Secretary of Health and Human Services. A vocal advocate for diet over medication (and interestingly, counsel to the above mentioned law firm Morgan & Morgan), RFK Jr is aligning with Agriculture Secretary Brooke Rollins to propose banning food stamp recipients from purchasing sugary drinks and so-called ‘junk food’. This initiative - developed in collaboration with Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency - aims to push healthier choices onto low-income consumers.

With all these regulations taking shape, one question remains: Will front-of-package labels and certifications actually change consumer behaviour?

A 2024 Georgetown University white paper - led by food policy expert Hank Cardello and nutrition expert and adjunct professor Dr Richard Black - examined existing global policies. Chile, for example, introduced aggressive black warning labels in 2016 to curb consumption of high-sugar, high-sodium and high-fat foods. While sales of targeted products fell, obesity rates continued to rise, suggesting these measures alone may not be enough.

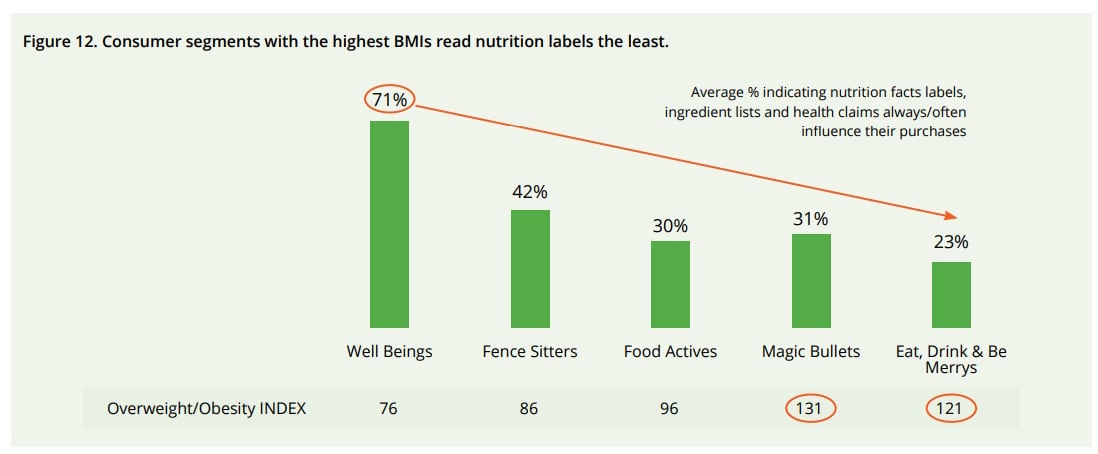

The study also found that consumers with the highest BMIs are the least likely to read nutrition labels. This raises concerns about whether labelling regulations will truly impact obesity rates or simply shift consumer purchases toward different processed foods. The authors suggest a more effective approach could involve positive reinforcement strategies, like Ahold Delhaize USA’s Guiding Stars system, which ranks foods as ‘good, better or best’.

The bakery and snacks sectors find themselves at the heart of this debate. From artisanal breads to mass-produced snack cakes, these products are scrutinised for their contributions to high sugar, fat and sodium consumption. According to Innova Market Insights, consumers associate certain categories more with ultra-processed foods than others. Ready-made meals are seen as the most ultra-processed category by 27% of consumers, followed by cakes, pastries, sweet goods and sugar confectionery. Interestingly, Boomers are found to be driving this consumer attitude, whereas Gen Z considers cookies and salty snacks as more ultra-processed.

Also read → ‘Industry’s latest bogeyman’: Does Superloaf prove that not all UPFs should be tarred with the same brush?The truth is there’s no universally accepted definition of what constitutes an ultra-processed product as yet. While the NOVA classification system is widely referenced, it lacks the precision needed for characterising or regulating individual foods.

According to the food classification system, UPFs are typically made from substances extracted from foods or derived from food constituents. They often contain numerous additives to enhance sensory appeal, making them highly convenient and attractive to consumers. However, they are also nutritionally unbalanced and prone to overconsumption, fuelling concerns over their health impact.

The Non-GMO Project’s Westgate shares this view. “The Standard American Diet has become one of the leading risk factors for death worldwide, yet navigating today’s food landscape can feel like an impossible task,” she said. “This isn’t by accident. When tobacco companies acquired major food manufacturers in the 1980s, they deliberately applied their expertise in addiction science to food engineering. The result was a new generation of ultra-processed foods designed with the same precision as cigarettes to trigger cravings and override our body’s natural satiety signals.”

Debate continues over whether NOVA categories should inform policymaking, with industry stakeholders cautioning against non-science-based decisions that lack clear, achievable health objectives. Critics warn of unintended consequences, such as food security risks, supply chain disruptions and rising costs.

Regulatory efforts have also led to initiatives like retail checkout bans and interpretive FOP labels. Some US cities – like Berkeley and Perris in California – banned candy and ‘junk food’ from checkout lanes in 2021. The Biden-Harris Administration’s 2022 National Strategy on Hunger, Nutrition and Health supported FOP labelling to ‘empower consumers’, a push expected to gain momentum under RJK Jr’s leadership.

However, past experience suggests limited success. In California, obesity continues to climb, and while Chile’s warning labels may have influenced purchasing behaviour, overall health outcomes did not improve—suggesting a substitution effect, where consumers may simply be shifting to other processed foods. The Pan American Journal of Public Health found that in Chile, childhood obesity initially declined following labelling reforms but later rebounded.

Then there’s the issue that the consumers most at risk are the least likely to read labels. Research from the Natural Marketing Institute (NMI) shows that people with the highest BMIs - who would benefit most from this information - are the least engaged with nutrition labels. Only 25-33% of high-BMI consumers read labels, compared to 71% of health-conscious individuals.

Taking it further, the Georgetown white paper argues that not all UPFs are nutritionally equal. Some, like mass-produced bread, serve as daily staples, while others, such as candy and sweet snacks, are consumed more occasionally. The study - funded by the National Confectioners Association (NCA) – suggests a differentiated approach rather than blanket regulations. “Consumers do not overconsume chocolate and candy, so targeting these foods will not impact obesity, write the authors. “An approach that focuses on product categories that consumers with the highest BMIs eat and drink the most will be more effective.”

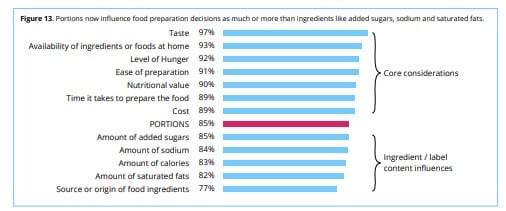

Rather than outright resistance, the food industry is pivoting toward portion control. The Georgetown report found that half of consumers actively seek smaller portion sizes, aligning with industry initiatives like the NCA’s ‘Always a Treat’ campaign, which advocates consumers enjoying indulgent foods in moderation.

As the debate over UPFs intensifies, the bakery and snacks sectors must find a middle ground between reformulation, transparency and consumer demand.

Retail bans and front-of-package warning labels may gain traction, but their long-term effectiveness is uncertain. A more strategic approach - differentiating UPFs by nutritional impact and promoting portion control - could provide a more sustainable solution. The industry’s future will depend on its ability to adapt, innovate and balance health concerns with consumer preferences for indulgence.

Studies:

S Dai, J Wellens, N Yang, et al. Ultra-processed foods and human health: An umbrella review and updated meta-analyses of observational evidence. Clinical Nutrition (2024) 43, 6, 1386-1394. doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2024.04.016

Von Hippel PT, Bogolasky Fliman F. Did child obesity decline after 2016 food regulations in Chile? Rev Panam Salud Publica. 2024 Mar 8;48:e16. doi: 10.26633/RPSP.2024.16