Tunnel of No return - The Times of India

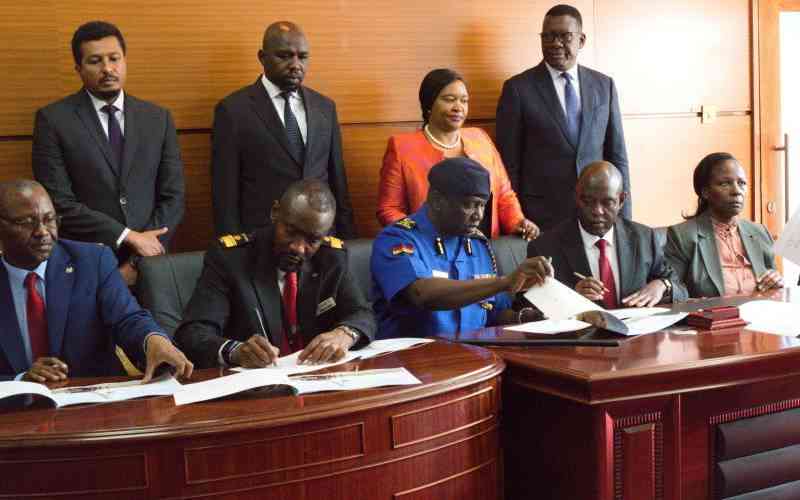

The

Wayanad twin tunnel project

, granted

environmental clearance

by the Kerala State Environmental Appraisal Committee (SEAC) on March 1, 2025, has sparked widespread concern over the future of

sustainable development

in the state. While the 8.75-km tunnel is touted as essential infrastructure to improve connectivity between Kerala and Karnataka, a closer examination reveals alarming ecological, geological, and social risks. Despite acknowledging these dangers, SEAC’s approval, accompanied by 25 conditions, fails to address the project’s core threats.

The proposed tunnel, connecting Anakkampoyil in Kozhikode to Kalladi in Wayanad, cuts through an ecologically sensitive area (ESA) rich in biodiversity. The region is home to schedule I and II species under the Wildlife Protection Act, including endangered birds like the Banasura Chilappan and Nilgiri Sholakili. It also serves as a critical elephant corridor, vital for the movement of wildlife. The project will fragment 17.26 hectares of forest, exacerbating habitat loss and increasing human-wildlife conflicts—a problem already rampant in Wayanad.

Moreover, the tunnel threatens four tribal hamlets, further marginalizing vulnerable communities. SEAC’s own report highlights these risks, yet the committee has chosen to overlook them, prioritizing infrastructure over ecological and social well-being.

Wayanad’s fragile terrain, prone to landslides, adds another layer of risk. The region witnessed devastating landslides in 2019 and 2024, yet the tunnel is planned through highly unstable ground. SEAC admits that blasting, tunneling, and seismic activity could trigger landslides, and unanticipated water ingress during construction could destabilize the landscape further. Shockingly, key geological and hydrological studies remain incomplete, leaving critical questions unanswered. Despite these glaring red flags, SEAC approved the project, with 25 conditions that fail to address any of these core issues.

The 25 conditions attached to the clearance are riddled with impracticalities and contradictions. For instance, one directive calls for ‘micro-scale mapping of landslide-prone zones’ in an area already classified as high-risk. Another mandates that ‘blasting should not cause surface vibration,’ a scientifically impossible requirement given that all tunneling methods generate vibrations capable of destabilizing the terrain.

Equally baffling is the condition to monitor the Banasura Chilappan bird population for genetic vulnerability. This is a meaningless gesture, as the project itself endangers the species and its habitat. Similarly, the recommendation to create an Appankappu elephant corridor is non-binding and hinges on additional land acquisition, which is unlikely to materialize. By the time such a corridor is established, the tunnel’s construction will have already fragmented habitats and intensified human-wildlife conflicts.

The budgetary allocations for environmental and social impact management further underscore the project’s lack of seriousness. Initially, a mere Rs 1.02 crore was set aside, a paltry sum that was later revised to Rs 15.04 crore—still only 0.7% of the total project cost. This amount is grossly insufficient to implement an effective environment management plan (EMP), raising doubts about SEAC’s commitment to genuine mitigation efforts.

SEAC’s approval process reveals a troubling pattern of negligence. The committee acknowledges the absence of essential geological and hydrological studies but does not require them as prerequisites for clearance. Instead, it asks the project proponent to submit a revised EMP within three months, with no consequences for non-compliance. This lack of accountability exemplifies a system where environmental clearances are reduced to bureaucratic smokescreens, devoid of genuine safeguards.

SEAC’s decision represents a profound institutional failure. The purpose of environmental clearance is to protect public safety and fragile ecosystems, not to facilitate their destruction. By approving a project, it admits is fundamentally unsafe, SEAC has failed its fundamental duty to uphold environmental integrity.

This approval, clearly granted under pressure and lacking sound reasoning, must be revoked. The Kerala State Environmental Impact Assessment Authority (SEIAA) must intervene and revoke SEAC’s approval. This is not just an environmental issue; it is a question of public safety. Legal action is imperative to halt this breach of environmental laws and ESA regulations.

The people of Wayanad and Kerala must hold the govt and regulatory bodies accountable, demanding transparency and sustainable development. Strong public resistance is essential to stop this project from turning into another environmental catastrophe.

The Wayanad twin tunnel project is not a symbol of progress but a potential engineered catastrophe. True development cannot be built on deceit, negligence, and the sacrifice of lives, livelihoods, and biodiversity. If this project proceeds, it will set a dangerous precedent where environmental clearances are reduced to mere formalities, regulatory bodies serve as facilitators of destruction, and irreversible damage is justified under the guise of progress. The question is not whether Kerala needs this tunnel, but whether it is willing to risk irreversible harm for a project even its approving committee deems unsafe.

The writer is an observer of sustainable development and policy-related issues