There is no evidence that AI causes brain damage. (Not yet anyway.)

There’s a new (unreviewed draft of a) scientific article out, examining the relationship between Large Language Model (LLM) use and brain functionality, which many reporters are incorrectly claiming shows proof that ChatGPT is damaging people’s brains.

As an educator and writer, I am concerned by the growing popularity of so-called AI writing programs like ChatGPT, Claude, and Google Gemini, which when used injudiciously can take all of the struggle and reward out of writing, and lead to carefully written work becoming undervalued. But as a psychologist and lifelong skeptic, I am forever dismayed by sloppy, sensationalistic reporting on neuroscience, and how eager the public is to believe any claim that sounds scary or comes paired with a grainy image of a brain scan.

So I wanted to take a moment today to unpack exactly what the study authors did, what they actually found, and what the results of their work might mean for anyone concerned about the rise of AI — or the ongoing problem of irresponsible science reporting.

If you don’t have time for 4,000 lovingly crafted words, here’s the tl;dr.

If you have the brain space for the full write-up, follow along:

Head author Nataliya Kosmyna and her colleagues at the MIT Media Lab set out to study how the use of large language models (LLMs) like ChatGPT affects students’ critical engagement with writing tasks, using electroencephalogram scans to monitor their brains’ electrical activity as they were writing. They also evaluated the quality of participants’ papers on several dimensions, and questioned them after the fact about what they remembered of their essays.

Each of the study’s 54 research subjects were brought in for four separate writing sessions over a period of four months. It was only during these writing tasks that students’ brain activity was monitored.

Prior research has shown that when individuals rely upon an LLM to complete a cognitively demanding task, they devote fewer of their own cognitive resources to that task, and use less critical thinking in their approach to that task. Researchers call this process of handing over the burden of intellectually demanding activities to a large language model cognitive offloading, and there is a concern voiced frequently in the literature that repeated cognitive offloading could diminish a person’s actual cognitive abilities over time or create AI dependence.

Now, , particularly since the tasks that people tend to offload to LLMs are repetitive, tedious, or unfulfilling ones that they’re required to complete for work and school and don’t otherwise value for themselves. It would be foolhardy to assume that simply because a person uses ChatGPT to summarize an assigned reading for a class that they have lost the ability to read, just as it would be wrong to assume that a person can’t add or subtract because they have used a calculator.

However, it’s unquestionable that LLM use has exploded across college campuses in recent years and rendered a great many introductory writing assignments irrelevant, and that educators are feeling the dread that their profession is no longer seen as important. I have written about this dread before — though I trace it back to government disinvestment in higher education and commodification of university degrees that dates back to Reagan, not to ChatGPT.

College educators have been treated like underpaid quiz-graders and degrees have been sold with very low barriers to completion for decades now, I have argued, and the rise of students submitting ChatGPT-written essays to be graded using ChatGPT-generated rubrics is really just a logical consequence of the profit motive that has already ravaged higher education. But I can’t say any of these longstanding economic developments have been positive for the quality of the education that we professors give out (or that it’s helped students remain motivated in their own learning process), so I do think it is fair that so many academics are concerned that widespread LLM use could lead to some kind of mental atrophy over time.

Rather, Kosmyna and colleagues brought their 54 study participants into the lab four separate times, and assigned them SAT-style essays to write, in exchange for a $100 stipend. The study participants did not earn any grade, and having a high-quality essay did not earn them any additional compensation. There was, therefore, very little personal incentive to try very hard at the essay-writing task, beyond whatever the participant already found gratifying about it.

At the outset of the study, participants were randomly assigned to one of three conditions, which they remained in for the first three writing periods of the study (at the fourth and final writing period, the “brain” and “LLM” groups were switched):

I think it’s important to highlight that last detail: subjects in the LLM group could not search for information to support their essays on their own; they had to rely upon OpenAI if they wanted to look up any information.

Whether it was possible for members of the LLM group to refuse to use OpenAI and write the essay entirely on their own, as the members of “brain only” group did, is unclear in the study protocol. As a researcher myself, I will point out that the silent pressure of demand characteristics within a study are nearly always there, so members of the LLM group probably guessed that they were expected to use AI to write their papers regardless. But when we think about how well Kosmyna et. al’s findings extend to real life, we do have to keep the artificiality of this in mind.

I will also point out that because this is an experimental study, Kosmyna and her colleagues are attempting to isolate the effect of using an LLM from any other variables that might influence essay quality or brain functioning.

It would require an extensive, highly expensive longitudinal design with data collection at far more time points to even begin to study larger questions like that. And that’s simply not what the research team is setting out to do here. And that’s fine! It’s important to have well-controlled laboratory studies that look into highly specific, short-term effects of using an LLM! The problem is that many reporters don’t seem to be aware of this, and are misreporting the study as being one on the long-term effects of using AI. It’s not.

Participants were given 20 minutes to write each of their essays, during which time they were hooked up to an electroencephalogram (or EEG) headset, which tracked electrical activity throughout the brain, in areas associated with word searching, word retrieval, creative demand, use of memory, executive functioning, cognitive engagement, and even motor engagement (because hey, typing up an essay requires more use of your hands that having OpenAI write it does!).

What’s been far less reported on is that the essays themselves were heavily analyzed for content, structure, and other markers of writing quality, and participants were asked to discuss their writing process and quizzed on how much they remembered about their essays. These measures make up a huge bulk of the study’s outcomes and conclusions, which gets a bit lost when the reporting is all about how AI use impacts subjects brain functioning.

A lot of the meatier conclusions in this study are rooted in regular-old human analysis of written content, and verbal feedback from participants; it’s a bit ironic that all the fear-mongering reporting about the dangers of AI falls back on shiny, impressive-looking brain imaging technology to back up its argument when the study itself treats qualitative human feedback as just as important. The public has always found studies more persuasive if they include brain imaging, even when the brain imaging data is highly tentative and flawed. It apparently looks more “sciencey” to people. It’s just a bit…odd to overly rely upon brain imaging data to report on a study that’s all about the pitfalls of falling for over-hyped tech.

So what did the researchers find? Here’s a summary of what the performance from the LLM group looked like, over the course of the four trials:

As you can see, the quality of essays written by the LLM group declined over time, as did the apparent amount of effort they placed into the process of writing. The first LLM-assisted essays had very little in the way of a unique voice, but participants did put some attention into using the OpenAI tool to translate information and augment their writing process. Overall though, they did not feel a strong sense of ownership of their essays and could not quote from their own papers when asked.

The amount of effort that participants placed into their essays declined over time. By the third time the LLM participants came into the laboratory, they essentially relied on the tool to write their essay entirely, and copy-pasted whatever it spit out into their submission. They did not appear to edit their work thoroughly, and what they submitted resembled what ChatGPT would put together by default on its own.

There was a great deal of homogeneity between the essays that LLM participants wrote. In the fourth trial, when they were now asked to write essays using only their brains, members of the LLM group suddenly performed far better, integrating content into their essays more and scoring above average, though they still underperformed compared to the subjects who had been writing the essays with only their brains in the other trials.

Participants in the LLM group were contrasted with both the Google group and the “brain only” group, whose essays on average were better quality. Generally speaking, the participants who were assigned to use only their brains to write their essays wrote more unique essays that could be distinguished from one another readily and actually varied in quality from writer to writer; they could also remember what they had written about and quote from it in detail, and when they switched to using OpenAI in the fourth and final trial of the study, they continued to use a bit more effort. They felt a stronger sense of ownership in their work than the LLM-using group did. (Members of the Google-using group generally fell in the middle, showing more engagement and investment in their essay writing than the OpenAI users, but less than the brain-only group).

I should point out here that the researchers analyzed participants’ essays and their interview feedback using AI, which might really shock the most vociferous of anti-AI alarmists who gravitated to this study as proof of ChatGPT’s ultimate evil. One of the primary analysis techniques in the study was NLP, or Natural Language Processing, and the team created a specially-trained AI model in order to perform it on their data:

Though the researchers’ overall wariness about LLMs being used within the classroom is evident in their article, their analytic techniques reveal that similar technology can be useful when applied to a specific task correctly, and cross-checked against human eyes. Numerous social science researchers now utilize AI to compile their datasets, clean out missing values and errors, perform basic analyses, organize findings into tables, place citations into a proper reference format, and even to generate their initial literature review — including some of the very researchers most concerned about AI! As we read through this work, we ought to bear this in mind.

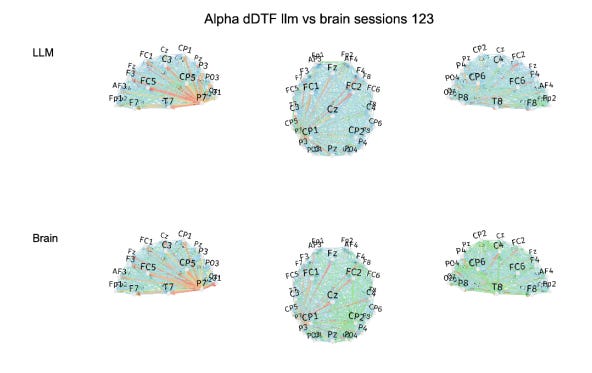

Let’s take a quick look at what the EEG data from the study shows:

Don’t these brain imaging results look rigorous and scientific? And they’re so difficult for a non-expert to read any results from, particularly when you take into account that most brain imaging studies rely upon heavy filtering and mathematical correction in order to isolate any significant effects because the data collection is so filled with noise and artifacts. Here’s what the same brain region looked like, when results are isolated only to the statistically significant effects (the more red the connectivity line shown is, the more significant the association found):

I won’t be overly glib here, because the overall work being done in this study is sound — the major bone that I have to pick is with science writers who seem to have no idea how easily neuroimaging results can be fabricated, and seem to not care to know. Overall, Kosmyna and her team did find significant differences in the cognitive engagement of participants while they were writing their essays, in several key areas of the brain:

All of these findings line up with the researchers’ overall expectations, and make conceptual sense. When people have the help of OpenAI to write essays (in a completely contrived laboratory setting where the quality of the essay literally does not matter to them at all), they put less attention into the task, try less, don’t bother searching their own memories for relevant words or facts, don’t exert a ton of self-control into making sure that they are writing at a high caliber, and eventually, after repeated writing exercises, they start just copying and pasting from the AI chat window into the submission box.

My question, though, is so what?

So what if a person who has no personal or external incentive to write an goddamned SAT essay well kinda dials it in?

So what if a person who is told by the researchers to use AI to write a paper winds up using AI, and cares less about the final product as a result?

So what if a person who uses AI to write a paper (again, because they were assigned to do so) reads it less carefully, remembers less of it, and feels like the essay is less “theirs”, compared to a person who…actually wrote the essay?

So what if a person who has been brought into a lab to make OpenAI write an essay three times really stops giving a shit by the third time, and puts even less attention into the (boring, unrewarding) task than they did before?

Is this not all a completely rational response to the situation these subjects have been put in? What person would continue to remain cognitively engaged and motivated by a task that has been designed to be both pointless and unenriching for them to take part in? Why would we ever expect a participant to write a beautiful, personalized essay when everything about the assignment pointed them toward doing as efficient and sloppy a job as possible?

These findings do not provide us with any evidence of long-term cognitive decline. Rather, what the study shows is that people do not try very hard when we give them no reason to try very hard. When there is no social recognition for a task, financial reward, professional reward, or enjoyment to be found in it, people do not care about it. That’s not brain damage or idiocracy, or even the devaluation of writing. It’s a rational choice. When a person does not try at a task that they do not care about, it isn’t laziness. It’s a logical use of resources. We might disagree with another person’s priorities, but what they’ve done makes perfect sense from where they are sitting.

And we can understand the growing use of Large Language Models in the classroom from this same perspective. Today’s generation of college students were told they had to go tens of thousands of dollars into debt to earn a college degree, not because it would provide personal enrichment or particularly help their career, but because holding that credential is pretty much mandatory to find employment in a lot of fields. In 70% of entry-level positions, a bachelor’s degree is now required. Students enter the academy out of desperation and economic coercion, and they are not trained to value the struggle of deep learning. And they, quite logically, approach the academic enterprise as a means to an end.

When they arrive on campus, these same jaded students are met with a teaching force that is predominately inexperienced graduate students and underpaid part-timers who are themselves being sorely exploited by a university system that loses more funding and cuts more teaching positions with each passing year.

These instructors who have been given very few resources to support their teaching and will receive no benefit for a stellar performance show the signs of their incentive structure in everything they do. And so they re-use reading lists they haven’t had the time to update since 1980. They “ungrade” and give everybody A’s because the students are just there for the piece of paper, and the administrators only care about keeping the enrollment numbers high, so it really doesn’t matter anyway. And yes, sometimes they write their exams and grade their papers using ChatGPT. Why shouldn’t they? Their luckier colleagues with tenure-track positions are using AI to analyze their data and write their emails, too; in a competitive publish-or-perish environment, each new piece of technology only increases the pressure to streamline, extends the necessity of doing ever more with even less.

So what if a student decides that their class papers do not matter in this environment? What reason does someone have to pour their heart and soul and brain capacity into choosing unique turns of phrase and researching novel examples? Who is going to read their paper? Who is going to care? And what value has been given to writing in such a disposable world?

Participants in the brain-only group had to use more of their working memory and cognitive resources to pen their essays. They had literally no other choice, and no other resources provided to them. And they produced more unique, memorable essays, and felt more invested in their work as a result. Circumstances motivated them to look inward and find out what memories and creative capacities were inside them. And if we want the next generation of writers to emerge with a real investment in the craft of writing and an ability to find the joy in it, we will have to give them reason to look, slowly, and carefully inward.

It is foolish, and defeatist, to say that today’s students have brain damage from using ChatGPT. What’s damaging are our incentive structures, which point at every moment toward carelessness and speed. But we can set things right at any time, and repair all of the damage that capitalism has done to us. We need only to create real challenges for ourselves that engage our wonderfully whole brains, and reason to believe that our efforts matter.

You can read the full paper (which I highly encourage!) for free here.