The Sound of Young Queer Scotland: An Interview with Carrie Marshall

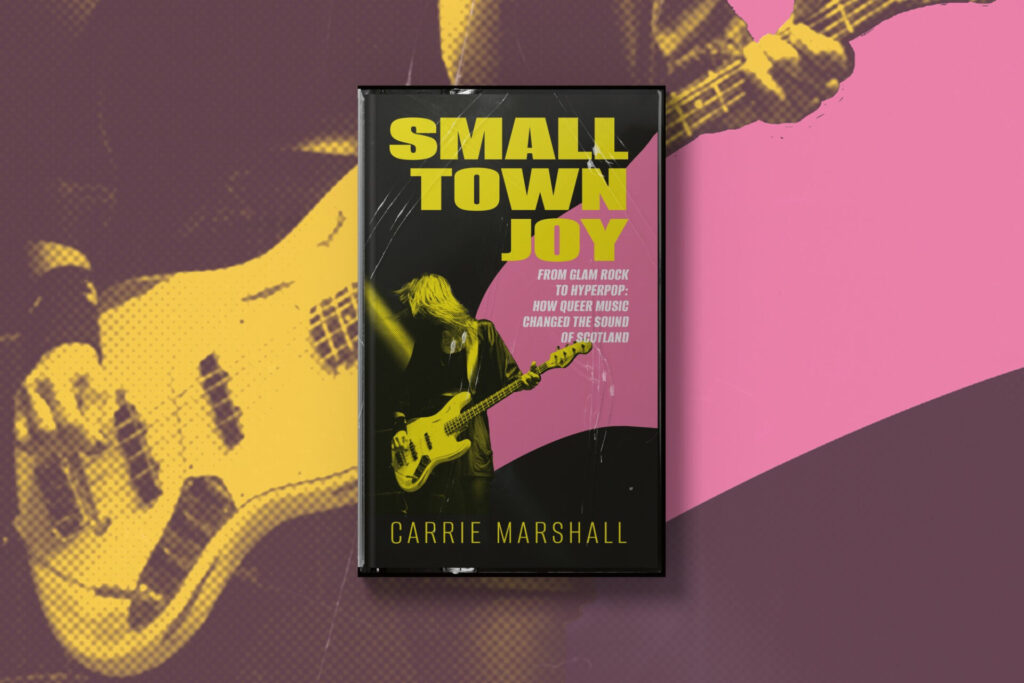

With the release of her new book Small Town Joy: From glam rock to hyperpop: how queer music changed the sound of Scotland, author Carrie Marshall talks to Claire Sawers about growing up in 1970s Lanark, clubbing at Edinburgh's Fire Island and the "seismic" influence of Jimmy Somerville

Carrie Marshall could see dark clouds on the horizon. Three years ago, she was promoting her new book Carrie Kills A Man, her memoir of coming out as a trans woman at the age of 44, and looking for her next writing project. Her autobiography described “throwing a hand grenade into a perfect life,” metaphorically killing off a depressed suburban dad. She wrote about the subsequent highs and lows of being a tattooed, middle-aged rock singer, now navigating fashion disasters, bigotry and being a trans co-parent.

“I decided I didn’t want to write a book about trans rights or anything like that,” she tells me over Zoom from her home in Glasgow. She’s wearing a grungy check shirt with a black Chvrches t-shirt underneath. We’re chatting a few weeks before her new book Small Town Joy is published. Its release happens to fall the week after the crushing UK Supreme Court decision on transgender people, part of the alarming roll back on protections for trans people around the world.

“Back then I could see a backlash coming, for trans and LGBTQ+ people in general. I wanted to write a book about joy. It was very deliberate – I wanted to talk about queer artists as the positive forces that they are. This music has made your life better! Even if you weren’t aware those musicians were queer, or their influences were queer, it is there in the music’s DNA. I wasn’t writing purely about the music either; I wanted to write about wider queer culture and the impact it can have on social change. We need that music to do that again as the dark clouds are gathering once more.”

And so it was that Marshall embarked upon a two and a half year project to research queer music in Scotland. Small Town Joy: From glam rock to hyperpop: how queer music changed the sound of Scotland is her wonderful, trivia packed, often fascinating and fangirling look at the LGBTQ+ artists that have shaped Scotland’s cultural landscape. She’s deliberately not aiming solely for a nostalgic, retromania style read either. After tracing historic lines, the second half of the book is a rich collection of her interviews and essays exploring current queer scenes, sometimes ones thriving in places where she least expects. (See her interviews with queer Scots trad folk musicians for example, or conversely, a notable lack of interviews with gay male rappers.)

Marshall’s timeline begins, not in Scotland, but in Harlem with the blues-singing lesbian ‘bulldaggers’ in the 1920s, and travels through the flamboyant cabaret artist Esquerita that inspired Little Richard, via the Beatles, the Bay City Rollers, Wendy Carlos, Siouxsie Sioux, Judas Priest, Buzzcocks, The Slits, The Associates, Sylvester, Orange Juice, The Pastels, the B-52s, Garbage, Optimo (Espacio), The Shamen, Finitribe, Derrick May, SOPHIE, TAALIAH, Lil Nas X and too many others to mention. Nope, not all those artists identify as queer or Scottish, but bear with her. Marshall didn’t want to write a “trainspottery book, gummed up with minutiae”. This isn’t meant to be an exhaustive list of queer Scottish musicians; rather “a story: one of music loved by LGBTQ+ Scots that queered the mainstream, influencing generations of musicians.” It’s that two-way osmosis that interests her: Scotland queering others and being queered.

Growing up in Scotland, Marshall devoured pop music, from deep inside the closet. “The early to mid 80s, that was my musical key period. Look how many absolute bangers came out in that short period of time!” We detour briefly into discussing Ian Wade’s book, 1984: The Year Pop Went Queer and I proudly flash my Pits and Perverts t-shirt, commemorating the fundraiser ball organised by Lesbians and Gays Support the Miners (LGSM) that same year, headlined by Bronski Beat.

“I was a pop kid. I got a lot of stick for liking ‘gay music’ like Erasure,” she remembers. “Others thought I should have been into rock by burly men with guitars. I was the only one of my social group that was really digging Pet Shop Boys, as one great example. Hearing songs like ‘It’s A Sin’, I was connecting with it in ways I didn’t understand at the time. Do you know that social media meme, ‘This better not awaken something in me?’ Back then, there were a lot of things going on – but if you’re in the closet you don’t necessarily want to put them all together because of what it might mean. Sometimes things are really obvious in the rear-view mirror though, later on when you understand your sexuality or gender identity better.”

Arguably one of the best chapters in the book is ‘I Feel Love’, Marshall’s ode to the glorious 1984 single ‘Smalltown Boy’ and the synth-pop icon, socialist and activist, Jimmy Somerville. Although Somerville prefers not to do interviews anymore, Marshall still manages to nail the enduring appeal of his music and his legacy in queer culture. Glasgow-born Somerville came of age in the context of Stonewall, the assassination of Harvey Milk, the AIDS epidemic and anti-gay panic in the UK, choosing to use his voice (an especially stunning one at that) to not only thrill, but to protest. To normalise gay existence and pushback against contemptuous attitudes towards the LGBTQ+ community. When The Age of Consent was released in 1984, Bronski Beat listed the gay age of consent for countries around the world on the album’s inner sleeve, with a phone number offering legal advice. That info was deleted before the American release, for fear of ruffling feathers.

Somerville still won’t be policed into silence – last year he took to his Facebook page, despairing at society’s regressions in many areas, and a real surge in homophobia, aggression and discrimination. “You know what?”, he typed. “Piss off! Just get on with your own life and let everyone else live theirs.” Marshall applauds Somerville’s blend of political dissent with timeless pop. “[Bronski Beat’s] effect, especially on LGBTQ+ listeners, was seismic.”

After describing Somerville’s sublime, soaring countertenor and, for its time, the groundbreaking social realism in the video for ‘Smalltown Boy’, Marshall writes: “The video for ‘Smalltown Boy’ was revolutionary in another key way: the band looked absolutely unremarkable. They weren’t Elton Johns or karma chameleons; they were just ordinary, the Bronksi boys next door. I don’t think you can overstate the importance of that. If you’re a smalltown boy, girl or nonbinary person it can perhaps be hard to see yourself in the more fabulous aspects of queer celebrity. I know I didn’t recognise myself in any of the very limited trans representation of the time.”

Although Somerville wasn’t available, Marshall does manage to chat with many of her heroes and key players in the queer community, whether or not they identify as queer. The reader can feel Marshall’s palpably enthusiastic connection with, say, the nonbinary, lesbian, soulful singer-songwriter Horse McDonald, who she goes to see perform “a passionate and ecstatic show” at Glasgow’s King’s Theatre Royal. Later she chats with her about growing up in 1970s Lanark. Horse shares that she was chased, harassed and attacked after coming out, but feels grateful to have given visibility to others in the closet. She talks about a woman who was at high school with her but chose not to come out at the time. The woman watched Horse’s career evolve from afar, and later, as an out gay woman, wrote Horse a letter saying that “knowing there were other people like her was life-changing.”

“There were no phones,” McDonald recalls. “There was no internet. I had no awareness of gay performers.” When Marshall asks them if things might have been different with more representation of queer artists, Horse agrees, “I think that makes a big difference. If we think we’re not alone, that we’re not carving this path ourselves, [that] someone else is going through what you’re going through, it’s a great comfort.”

Shirley Manson from Garbage talks with Marshall about allyship and the ongoing fight for LGBTQ+ rights, while reflecting on how things once used to be. “Back then, when we released ‘Androgyny’ and ‘Cherry Lips’ and ‘Queer’, there was no language in common for us to discuss, to explain, to describe, to glorify gender fluidity and the breaking of the binary. We just didn’t have that language and now we really do.”

Elsewhere, Keith McIvor – better known as JD Twitch, one half of Optimo (Espacio) – reminisces about the legendary gay nightclub, Fire Island, which ran in Edinburgh between 1978 and 1988. It was part of the inspiration for James Ley’s 2017 play Love Song to Lavender Menace. Fire Island was not only a mecca for dancers, it was pioneering; a portal through which house music first entered Scotland. “The gay DJs in Glasgow and Edinburgh were really leading the way,” says McIvor. I was straight, but I’d go to Fire Island because it was so welcoming.” Fire Island’s inclusive atmosphere undeniably influenced Optimo’s famously eclectic music policy and warm dancefloor vibes – plus McIvor remembers how the rise of ecstasy in clubs allowed the scene to evolve further.

“The whole dynamic changed,” he recalls, despite not dabbling in drugs himself. “Previously you’d go to mainstream clubs and guys would dance with their girlfriends or with other girls, and nobody else. Then the minute people started taking X, everyone’s dancing with everyone. Whatever you think about drugs, it was a positive thing that opened up a lot of people’s minds. They were a lot more open to being with people from different backgrounds, from different sexualities. It really did knock down a lot of barriers.”

Describing being a member of the queer community as “playing life on hard mode,” particularly in the current climate, Marshall hopes Small Town Joy will beam an affectionate spotlight on past and present queer scenes and encourage folks to get out and see more queer artists performing.

“What I’m hoping is that people will read my book and go, ‘What else is there out there?’”

“Music has given me moments of absolute euphoria – being dragged up to dance to Robyn recently by a good friend – or a sense that I wasn’t alone. My book is not only a celebration but sometimes a provocation. Queer music can shift culture.”

“When you’re young, we probably all feel that music really speaks to you. But there’s this extra strong connection with queer artists; you’re yearning to be told everything’s ok and to find people like you. When you find that, it can be enormously powerful.”

Small Town Joy: From glam rock to hyperpop: how queer music changed the sound of Scotland by Carrie Marshall is published by 404 Ink