The Israel-Gaza tragedy and Europe's responsibility

for the people living there, a moral and political disaster for Israel, the indirect, long-term result of past European barbarism and the subject of a damaging present European failure.

Hamas's terrorist attack on 7 October 2023 was a horrendous atrocity and Israel clearly had both the right and the duty to respond to it – as also to the way Hezbollah joined the attack from Lebanon the next day. An Israeli military response, wisely and proportionately conducted, could have met the criteria for a just war. But unless you think two former Israeli prime ministers, the president of the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC) and 828 British lawyers are all anti-semites and blood-libellers, you should probably accept that the way the government of Benjamin Netanyahu has subsequently conducted this war has violated international humanitarian law and involved the commission of war crimes. 'Yes, Israel is committing war crimes,' concluded Ehud Olmert, prime minister from 2006-09, in an article in Haaretz.

Another former prime minister, Ehud Barak, says Netanyahu 'is not acting in the national interest; he is acting purely for self-preservation. Every other argument is a smokescreen.' Recall that one of the criteria for a just war is 'right intention'. It would be beyond naive to attribute that to the current Israeli prime minister. One can go down the list of conditions for a just war, both for going to war (ius ad bellum) and for how you wage it (ius in bello), and see how many are now being violated. Proportionality? No. Reasonable chance of success? No. Distinguishing between combatants and innocent civilians? No.

Mirjana Spoljaric, president of the scrupulously neutral ICRC, the custodian of the Geneva Conventions, recently told the BBC's Jeremy Bowen that what's happening in Gaza is now 'worse' than her previous description of it as 'hell on earth'. It surpasses 'any acceptable legal, moral and humane standard'. Addressing both Hamas and Israel, she said 'There's no excuse for hostage-taking. There is no excuse to (sic) depriving children from their access to food, health and security. There are rules in the conduct of hostilities that every party to every conflict has to respect.'

An open letter to British prime minister Keir Starmer from 828 UK-based or UK-qualified lawyers, legal scholars and former judges is particularly useful because it's accompanied by a 'legal memorandum' which musters in detail the evidence for the claims. It cites a UN estimate that as of 22 March 2025 at least 53,000 Palestinians had died and more than 121,000 been injured since the beginning of the Israeli military operation in Gaza. An estimated 70% of verified fatalities were women and children. It also quotes a Save the Children Fund report that Gaza now has the highest proportion of child amputees anywhere in the world (with many of the amputations being carried out without anaesthetic). The memorandum focuses sharply on Israel's blockade of humanitarian aid to the people of Gaza for more than two months after 2 March 2025, which according to UN sources has now resulted in widespread starvation, and the unilateral resumption of hostilities by the Netanyahu government last month. It spells out the legal grounds on which the letter concludes that Israel is committing 'war crimes, crimes against humanity and serious violations of international humanitarian law'.

: I try to write about things I know about. I have no expert knowledge of the Middle East, nor anything to contribute from first-hand experience there. Yet the relentless daily scenes of innocent suffering, Palestinian and Jewish (in the case of the hostages and their relatives), have become so overwhelmingly oppressive to the spirit and conscience that in the end I feel compelled to do so. As Bertolt Brecht wrote, there are times when 'a conversation about trees is almost a crime/ because it involves being silent about so many misdeeds'.

I do worry about the danger of purely performative virtue-signalling. (A recent protest letter signed by a long list of writers contains the portentously self-important formulation 'this is about our moral fitness as the writers of our time'.) I've no illusion that what I say will change anything, except perhaps to a tiny degree in some corner of the European debate. But through the personal, informal format of a Substack newsletter – not a final, finished article – I can try to think aloud about one aspect of this tragedy close to both my personal and professional concerns: Europe's responsibility.

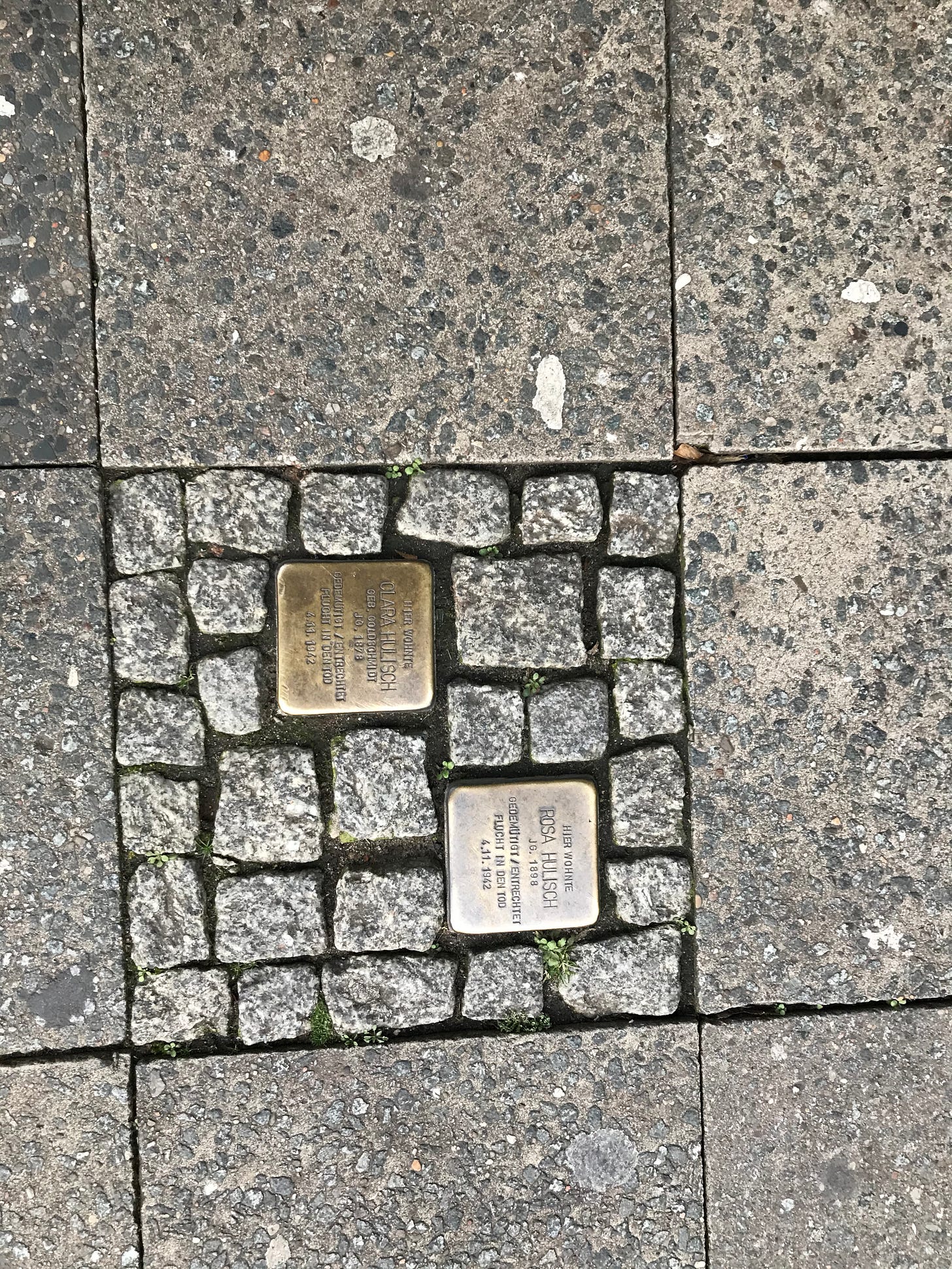

It was the pogroms of the late 19th and early 20th century, mainly on the territory of the Russian Empire, that kickstarted the waves of Jewish emigration to Palestine. The Zionists shared with many others in central and eastern Europe at that time the conviction that only having your own sovereign state would secure your people's safety, freedom and collective future. It was then Nazi Germany's attempt to exterminate all the Jews of Europe, now widely known as the Holocaust or Shoah, that gave the decisive push for both the creation of the state of Israel and widespread international acceptance of its legitimacy. In that sense, the innocent Palestinians who were driven out of their homes and off their family lands in 1948 – and since – have been paying the price for European barbarism.

This historic responsibility has led many Europeans, and especially Germans, to feel a very special sympathy for and responsibility towards the Jewish state. I feel it very strongly myself. Ever since I started studying the history of Nazi Germany some 50 years ago, the Holocaust has been central to the way I think not just about Europe, and what we are trying to do on our own continent, but also about how Europeans should speak and act in the world. If I'm honest, I hate to think, and even in my heart of hearts find it difficult to accept, that a Jewish state can behave in this way.

So, obviously, do some Israelis. This is surely how we must understand the agonised comment by opposition politician Yair Golan – son of a refugee from Nazi Germany and a former deputy chief of staff of the Israel Defence Forces (IDF) who personally dashed to rescue several Israelis threatened by the Hamas massacre on 7 October – that 'a sane country doesn't wage war against civilians, doesn't kill babies as a hobby and doesn't set for itself the goal of expelling a population'.

As Nathalie Tocci points out in the Guardian, the positions taken by individual European countries have been very different. But overall – not least because the EU has to seek consensus positions between 27 member states – Europe has been painfully slow to speak out against the Netanyahu government's violations of the international norms that Europe always claims to uphold.

Understandably, given Germany's unique historical responsibility for the Holocaust, German intellectuals and politicians have agonised about this. But over the months since October 2023, I have watched many of them go through intellectual contortions, diplomatic evasions and manifestations of deep psychological denial to avoid following the simple injunction attributed to John Maynard Keynes: 'When the facts change, I change my mind. What do you do?'.

Much too often the reaction has been 'you can't say that!', when the 'that' in question was a critique that should be debated, not silenced. In 2023, the city of Bremen and the Heinrich Böll Foundation withdrew their co-hosting of the Hannah Arendt Prize for Masha Gessen in response to a New Yorker essay in which the Jewish-Russian-American writer compared Gaza to a Jewish ghetto in Nazi-occupied eastern Europe. If you read the essay, you see that it is a long, thoughtful, complex engagement with the use and abuse of the memory of the Holocaust in countries including Germany, Poland and Ukraine. You can agree or disagree, but it's a text worthy of serious engagement, not cancelling. When the prize ceremony finally went ahead in a much smaller space, Gessen made what should be an obvious point: to compare is not to equate.

Another intellectual who was criticised for thinking critically about Israel's response to the Hamas atrocity was the Jewish-American-German philosopher Susan Neiman. Neiman, who in 2019 published a whole book arguing that we can learn from the Germans how to deal with difficult pasts, now concluded that they didn't know how to deal with a difficult present.

The German government's representative for combating anti-Semitism, Felix Klein, said a description of Israeli policy as apartheid oversteps the line from legitimate criticism of Israel to anti-Semitism – thus effectively characterising the UN’s highest court, the International Court of Justice, which has made the apartheid comparison, as anti-Semitic. In a TV interview last month, the mayor of Hamburg, Peter Tschentscher, continued to put all the blame for everything that is happening in Gaza on Hamas, helpfully explaining that Israel needs 'Lebensraum'.

One can perhaps understand how in late October 2023, just a few weeks after the Hamas atrocity, then German chancellor Olaf Scholz might insist he had 'no doubt' that the IDF would abide by international law. But as recently as mid-May 2025, when Israel had already blocked all humanitarian aid to Gaza for more than two months, the new German foreign minister Johann Wadephul, on a visit to Israel, said of the widely criticised and patently inadequate alternative aid mechanism just proposed by the Israeli government: 'Inasmuch as the Israeli side now takes this step it's clear that one can't accuse Israel of conduct incompatible with international law' (my italics). In face of all the evidence from the last 20 months, this amounts to little more than the famous 'Weil nicht sein kann was nicht sein darf' (because what may not be cannot be) of a German nonsense poet.

is the claim, made by then Chancellor Angela Merkel in the Knesset in 2008 and often repeated since, that the security of the state of Israel is part of the Staatsräson, the raison d'état, of the Federal Republic of Germany. There are at least three problems with this fine-sounding declaration. First, the very notion of raison d'état harks back to an older European tradition of giving absolute priority to the vital interests of a state. This is hard to reconcile with the post-1945 idea of rules-based international order, tirelessly endorsed by German leaders. As Roger Scruton explains in his excellent Dictionary of Political Thought, the invocation of raison d'état implies that the vital interests of the state 'override all countervailing considerations, in particular those of an international character'.

Second, even if you think the vital interests of Israel are the vital interests of Germany, it is increasingly clear that what Netanyahu is doing will be immensely damaging in the longer term to the vital interests of Israel. A true friend would point this out, not abet him in his self-serving folly. (Recent remarks by the new German Chancellor, Friedrich Merz, following strongly worded criticism from Canada, Britain and France, suggest that this message may finally be getting through.) Misusing the charge of anti-Semitism and instrumentalising the memory of the Holocaust, as Netanyahu does, to disqualify any criticism of his government's conduct of war, will likely end up stoking anti-Semitism and weakening the deterrent effect of the memory of the Holocaust.

Finally, not one but two imperatives follow from the unique German responsibility for the Holocaust: a particular imperative, always to stand by the state of Israel, and a universal imperative, always to stand up for human dignity and human rights wherever these are violated. In Gaza, the two imperatives clash. It's simply not good enough to put the telescope to your blind eye, like the British admiral Lord Nelson, and say 'I see no clash'. You might think that the land of Immanuel Kant, of all places, would understand that when a particular imperative stands in tension with a universal one, the universal must never be sacrificed to the particular.

, contemplate these muddled, hesitant and sometimes outright denialist European reactions and cry 'double standards!'. This gravely damages our credibility when denouncing violations of international humanitarian law elsewhere, for example in Ukraine. The problem of double standards is an old one. In the 18th-century, the countries in which Enlightenment universalism was first proclaimed only offered equal dignity and rights to a small minority of propertied men; not to slaves, not to poorer men, not to women, and not to the rest of humankind. But gradually, haltingly, over the centuries, we tried to bring the reality of our own societies, and even of our international policies, closer to the ideal. Always imperfectly, always inadequately, always with a large remaining dose of hypocrisy – but nonetheless trying to move in that direction.

For the last decade or so, we have been retreating rather than advancing in this endeavour (just think about European policy towards Turkey), especially under the pressure of the anti-liberal populist nationalists who are making the running in our politics. What might be called the Ukraine-Gaza Gap is a further blow to the credibility of liberal Europe, at home and abroad. Josep Borrell, the last EU high representative for foreign and security policy, expressed this powerfully in his 2024 Dahrendorf Lecture at the European Studies Centre at Oxford University. (Full disclosure: I was responsible for the event.) Having self-ironically reflected that he used to tell his ambassadors that 'diplomacy is the art of managing double standards', Borrell went on to explain how damaging to Europe's international credibility is 'the perception… that we value civilian lives in Ukraine more than we do in Gaza'. And, he insisted, 'if we call something a war crime in one place, we need to call it by the same name in any other'.

For the avoidance of doubt: this is not to suggest, in any way, shape or form, that what is happening in Gaza is the same as what is happening in Ukraine. The full-scale Russo-Ukrainian war did not begin with a bunch of Ukrainian terrorists murdering, torturing, raping and kidnapping innocent Russians. Russia is the sole aggressor in that case. To put the blame for this one exclusively on Israel is another kind of intellectual and moral failure – one also quite widely encountered in Europe. If Hamas released the remaining hostages, it would be difficult, if not impossible, for Netanyahu's government to continue prosecuting the war. Hundreds of thousands of Israelis have demonstrated against Netanyahu and for a peace deal to release the hostages. Israel's very existence is threatened by powerful neighbours such as Iran, so in that sense it’s more comparable to Ukraine.

But of course Israel is neither the Russia nor the Ukraine of the Middle East. To compare is not to equate. The point here is not to suggest any equivalence. It's simply about moral and political consistency in confronting war crimes and violations of international humanitarian law wherever they occur. One European country that has been admirably consistent in this respect is Norway, as the country's deputy foreign minister explained in a recent podcast with ECFR's Mark Leonard.

to respond adequately to the Israel-Gaza tragedy is so damaging. It's also in our own societies. The crisis has exacerbated tensions between Europe's Jewish and Muslim communities. Anti-Semitism has increased to an alarming degree, and anti-Muslim hatred has also been on the rise. For many young Europeans, as I know from talking to our students here at Oxford, Europe's response to Gaza has made the rhetoric of liberal European leaders seem even less convincing than they thought it already (because of liberal Europe's failure to deliver on other promises). I talk about Ukraine and they say 'what about Gaza?'.

'But,' some critics exclaim, 'the students' language on Gaza is extreme, hysterical, utterly one-sided!' Well, the old 68ers who solemnly rebuke today's students for their 'Stop Genocide in Palestine' campaigns might usefully remember the extreme rhetoric they themselves used back in their own student activist days, on which they now look back with self-indulgent nostalgia. Now as then, you need to separate the wheat from the chaff, the good impulses from the dangerous nonsense; encourage and support the former, expose and resist the latter. And yes, especially when outside extremist agitators become involved, this does sometimes spill over into vile anti-Semitism, which should be combated with all the legitimate means at our disposal.

If this essay were an op-ed, it might conclude with one of those generally powerless admonitions that governments 'must' take action X or Y. (I've done it myself all too often, and usually to no effect. 'We must stop saying "must'!' a Guardian editor recently quipped, as we discussed the headline for one of my columns.) Certainly I think that, at a minimum, Germany – by far the largest arms supplier to Israel after the US – and other European countries (including Britain) should supply no more weapons while Israel is preventing adequate food and medical supplies getting to starving people in Gaza. And I hope France, Britain and Germany will join other European countries in the diplomatic recognition of a Palestinian state. If we believe that the only way forward to a lasting peace remains a two-state-solution, let's start by recognising two states. But everybody knows the only outside power that can decisively change Netanyahu's course is the United States.

Anyway, this is not an op-ed, just a personal attempt to think aloud about an agonising subject, with special reference to our own European responsibility, past and present. Obviously the most important thing is that the suffering of so many innocent Palestinians and (in the case of the hostages, their relatives and those protesting for their negotiated release) innocent Israelis should cease as soon as possible. But we will also need to reflect on these 20 months of European hesitation, confusion, denial and double standards. This has helped no one. Not the Palestinians. Not Israel. Not Ukraine. Not Germany. Not Europe as a whole – neither at home or abroad.

This is one of a number of texts that I am writing exclusively for this Substack newsletter (as well as reproducing here articles published elsewhere). They take time to write. I’m still happy to offer these for free. If, however, you do choose to take a paid subscription, you will have access to the entire archive of this newsletter in which - as its name suggests - I have been chronicling the history of the present since 2022. For paid subscribers, there will also be special opportunities to make comments and pose questions to which I will respond directly.