Modern venture capital traces its roots to the post-WWII era. In 1946, was founded by Georges Doriot as one of the first venture firms. ARDC was a publicly traded vehicle that raised capital from outside the traditional wealthy-family circles (including institutional money) – a revolutionary idea at the time. ARDC’s landmark success came with its 1957 investment of $70,000 in Digital Equipment Corporation (DEC) (for 70 % ownership) plus a $2 million loan, which turned into many times that value after DEC’s IPO in 1966. This demonstrated the venture model’s potential: high-risk equity investment in technology startups could yield outsized returns.

Yet, ARDC was not a “fund” in today’s sense; it operated more as an evergreen investment company and even took majority stakes (e.g., 77 % of DEC). The true emerged in 1958–59, when ARDC alumni and others set up the first limited partnerships. Notably, formed a – structured as a 10-year limited partnership with a 2.5 % annual management fee and 20 % carried interest for the GPs. This became the blueprint for virtually all VC funds thereafter. The alignment of incentives was clear: GPs (general partners) only profit significantly if investments succeed (via carry), aligning them with LPs (limited partners). DGA’s success inspired others: in 1961 Arthur Rock co-founded , another 2 & 20 fund that, among other deals, invested in Fairchild Semiconductor and later Intel. followed in 1965, founded by ARDC veterans and likewise adopting the limited-partnership format. By the late 1960s, the basic and of venture investing were in place.

Early Silicon Valley received critical DNA from these proto-VC efforts. For example, when helped eight defectors from Shockley Labs (the “Traitorous Eight”) form in 1957, a key condition was equity ownership for the technical founders – a sharp break from the norm of large corporations. This ethos of giving founders and early employees substantial stock (and later, stock options) became a governance norm transferred to Silicon Valley startups. It aligned talent with investors, mirroring the GP/LP alignment at the fund level. Additionally, early venture deals established that VCs would often take board seats and actively mentor companies – a practice Doriot himself espoused, as he taught entrepreneurship at Harvard. of gains was also present: ARDC, as a public VC, could reinvest its profits continuously, whereas the new LP funds wrote provisions to reinvest early returns into new deals within the fund’s life. These practices – active governance, equity incentives, and long-term commitment of capital – formed the cultural and structural bedrock for venture capital. All these would prove prescient for the crypto era, which would grapple with aligning decentralized project teams with investors in new ways.

By the late 1960s, venture capital was still a relatively small, clubby industry, but it was about to scale massively. Key policy shifts in the 1970s unlocked institutional money, transforming VC into a mainstream asset class. A pivotal change came with the 1978 US Revenue Act, which , dramatically increasing the after-tax returns from successful venture investments. Almost immediately, capital flowed in: new commitments to VC funds jumped from a mere $68 million in 1977 to nearly $1 billion in 1978. Then in 1979, the Department of Labor clarified the , explicitly . This was a game-changer – vast pools of capital that had been off-limits (pensions, insurance) could now seek the higher returns of VC. By 1983, annual new commitments to venture funds exceeded $5 billion, up more than 50 × from the mid-1970s. In short, : the twin boosts of a friendly tax regime and pension-fund participation gave the industry a long-term capital base it never had before. (For context, many of the LPs now allocating to crypto funds – endowments, family offices, etc. – first entered venture in this era of newfound legitimacy and attractive returns.)

The saw venture capital mature alongside the computer and internet industries. The further spurred innovation (and indirectly VC deal flow) by allowing universities and small businesses to , leading to a wave of (particularly in biotech and computer science). Venture firms eagerly backed these tech-transfer companies, bridging lab innovations to market – a precedent for how crypto VC would later fund open-source protocol developers spinning out of research labs and hacker communities.

Throughout the ’80s, VC grew steadily, then exuberantly in the ’90s. The IPO (e.g., in biotech, in personal computing) provided successful exits that proved the VC model at scale. In 1980 alone, 88 VC-backed companies went public. The subsequent stock-market crash of 1987 caused a brief dip, but by the was underway. Venture investment exploded in the latter half of the ’90s, peaking in 1999 – the year of – when U.S. VC investment across all sectors hit an unprecedented ~$105 billion (in 2021 dollars). Venture capital had gone from a cottage industry to a driving force of the economy, and Silicon Valley became synonymous with high-growth startups. Crucially, the : even as fund sizes grew (from tens of millions in the ’60s to hundreds of millions by the ’90s), the 2 % / 20 % fee-carry model and ~10-year life remained standard, aligning big rewards for GPs with big outcomes for companies. Funds launched in this era (Sequoia, Kleiner Perkins, Accel, NEA, etc.) institutionalized investment committees, rigorous due-diligence processes, and (like reserving capital for follow-ons) that would later be adopted by crypto funds seeking similar professionalization.

One specific structural innovation was the . In 1980s Silicon Valley, it became standard that ~10 – 20 % of a startup’s equity be set aside as options to attract and retain talent. This practice originated from success stories like Apple and Microsoft, which minted millionaire employees and thus drew waves of skilled labor into startups. It ingrained the idea of in tech companies, aligning employees with investors and founders. Later, crypto projects would emulate this through mechanisms like token allocations for core contributors – effectively, token options. The DNA of incentive alignment runs straight from the Fairchild/HP era of stock options to modern token-vesting schedules.

also evolved: VCs in the ’80s and ’90s became deeply involved in company strategy, often taking board seats commensurate with their ownership. They emphasized milestones, professional management (sometimes even ousting founders in favor of seasoned CEOs), and staged financing (tranches released as KPIs hit). While some of these hands-on practices clash with the decentralized, founder-centric ethos of crypto, the underlying principle of carried forward. Even crypto funds today often use SAFEs/SAFTs with board-observer rights or on-chain governance participation, reflecting the idea that capital comes with guidance and accountability – a norm set in this institutional VC age.

The institutionalization era taught that venture capital is highly cyclical and sensitive to policy and macro shifts. The late ’90s dot-com underscored that soaring investment volumes can presage painful corrections – 2000 was a “high-water mark… not again replicated until 2020” for overall venture funding. When the bubble burst, many VC funds and LPs saw negative returns, leading to a pullback in the early 2000s. This memory echoed in crypto: 20 years later, the ICO boom and 2021 boom would follow a similar boom-bust-investor-exodus pattern. The lesson for long-term LPs was to commit to the asset class through cycles and be wary of hype phases – wisdom equally applicable to crypto VC allocation now. Crucially, the regulatory and structural innovations (prudent-man rule, capital-gains tax rates, university tech-transfer policies) set precedents for how external factors can unlock new capital for venture – analogous to how clear crypto regulation or new financial instruments (ETFs, etc.) could unlock fresh capital for crypto markets. In essence, by 1999 the venture industry’s had branches around the world, robust best practices, and a track record that would soon inspire the first funds dedicated to an emerging technology called cryptocurrency.

The turn of the millennium brought the , a major inflection point. After 2000, venture capital sharply contracted as the and startup failures triggered a funding drought from 2001–2003. VC investment plunged ~80% from 2000 to 2002, and many late-90s funds delivered poor returns. This painful reset parallels crypto’s 2018 "crypto winter" and 2022 downturn—markets that surge can crash, with rewards often coming in the next cycle. Indeed, venture capital recovered gradually in the mid-2000s, driven by (social media, SaaS) and later the (smartphones, apps). By 2007–2008, companies like Facebook and YouTube emerged, and Apple's 2007 iPhone unlocked a new app economy. However, total VC funding didn’t surpass the 2000 peak again until 2020, underscoring the need for patience—a cautionary note for crypto investors after the 2021 highs and subsequent 2022–2023 slump.

A key 2000s shift was startups staying private longer. While IPOs typically occurred within 4–5 years in the 1990s, by the late 2000s, companies like Facebook took around 8 years (2004–2012), and Uber even longer. This was partly due to abundant late-stage capital and regulatory burdens like the 2002 Sarbanes-Oxley Act. Longer liquidity paths prompted the emergence of around 2007–2009, with platforms like (founded by Barry Silbert) and facilitating trading in pre-IPO shares of companies such as Facebook, LinkedIn, and Twitter, especially after the 2008 crisis stalled IPOs.

SecondMarket initially traded illiquid assets but found its niche in private tech stocks by 2009, notably Facebook shares. By 2010–2011, SecondMarket and SharesPost regularly enabled secondary trading, foreshadowing crypto token liquidity dynamics. These platforms demonstrated appetite for liquidity before traditional exits and provided price discovery for private assets-proto-exchanges for venture assets, akin to modern crypto exchanges.

Significantly, secondary markets broadened investor participation (hedge funds, pre-IPO funds, wealthy individuals) into late-stage companies, analogous to ICOs and token offerings enabling broader, faster global investment in early-stage tech projects. ICOs can be seen as extending this secondary-market trend, offering direct, immediate liquidity by issuing tokens instead of shares.

Secondary markets introduced friction, prompting firms like Facebook to impose transfer restrictions. This mirrors crypto debates on token float control. Regulators also intervened, with SEC rules (500-shareholder-rule modifications, Reg A+ and CF expansions) modernizing private-share trading, paralleling today’s regulatory efforts for token markets.

The wider 2000s venture scene saw other innovations and challenges. Post-dot-com bust scrutiny questioned the traditional VC model, prompting experiments with corporate venture arms and venture debt. Global VC expanded rapidly, particularly in Europe and Asia, supported by government initiatives, ending Silicon Valley’s monopoly. Crypto’s inherently global nature amplified this trend, with early global developer communities and ICO activity. By 2010, venture capital had a playbook for global scale that crypto funds later adopted.

The 2000s taught VC vital lessons in liquidity management and adaptability, prefiguring crypto’s innovations. Secondary markets anticipated token vesting and early liquidity-both serving investors seeking quicker exits than traditional timelines. The decade’s innovations (secondary exchanges, private-stock trading frameworks) laid foundations turbo-charged by crypto’s 24/7 global trading. Limited partners examining the 2000s recognize cyclical patterns and early-liquidity mechanisms essential for assessing crypto VC today.

The launch of – amid the Great Recession – introduced a radically new concept: a decentralized, digital form of money and store of value, powered by blockchain technology. Yet in these formative years, institutional venture capital paid scant attention. Bitcoin’s emergence was driven by cypherpunks, cryptographers, and hobbyists on forums, not the halls of Sand Hill Road. Funding for Bitcoin-related endeavors came mostly from personal passion (early miners reinvesting their coins) and a few who were true believers. For example, Roger Ver (often called “Bitcoin Jesus”) funded several Bitcoin startups early on, and Jed McCaleb created and sold the Mt. Gox exchange largely self-funded. But the . In fact, in all of 2012, Bitcoin startups raised only about in venture capital combined – essentially a rounding error in global VC statistics. By comparison, that same year saw overall VC investment around $50 billion globally. Bitcoin was invisible in portfolios.

Several factors were significant:

Despite mainstream hesitation, specialized investors emerged. In 2012, Barry Silbert founded , an early angel fund for Bitcoin startups (later becoming Digital Currency Group). Additionally, Adam Draper’s Silicon Valley incubator launched a Bitcoin-focused accelerator in 2013, providing crucial early support. These entities operated at the fringes until Bitcoin’s price surge to $1,000 in 2013 finally drew mainstream VC attention.

The situation resembled the pre-venture era of early tech - like how in the 1930s and early ’40s, innovative projects were funded by government grants or hobbyists because formal venture capital didn’t exist until after WWII. Bitcoin in 2009–2012 was nurtured by its community and a libertarian/open-source ethos rather than VC money, highlighting that transformational innovations can gestate outside conventional funding channels. For LPs and observers, this era is a reminder that ; sometimes the opportunity needs to ripen. By 2013, as we’ll see, that ripening occurred and the First Crypto VC Wave began – marking the true start of venture capital genealogy branching into blockchain.

was a breakout year for crypto venture. Bitcoin’s price surged (from ~$13 in Jan to over $1,000 by Dec), grabbing headlines and forcing tech investors to pay attention. More importantly, real startups formed around Bitcoin and other nascent cryptocurrencies, providing investable equity for VCs. The result: venture capital investment in crypto jumped dramatically. In 2013, blockchain/Bitcoin startups raised on the order of in VC – up from virtually $0 the year before. It was still tiny by VC standards, but the trajectory had changed.

Several in this first crypto-VC wave illustrate how classical VCs adapted to this new domain:

By 2016, the concept of or convertible notes that might convert into tokens was emerging in legal circles, anticipating the ICO wave. Traditional VC agreements began sprinkling in clauses about tokens. For example, an investment in a protocol startup might say: if the company ever issues a utility token, investors either get a certain allotment or the option to acquire tokens at a discount. This was a direct adaptation to crypto risk – namely, the risk that value would shift from equity to a token not originally contemplated. These contract tweaks were still evolving and not widely standardized until the SAFT in late 2017, but their roots lie in these 2013–2016 deals as pioneers felt out the new territory.

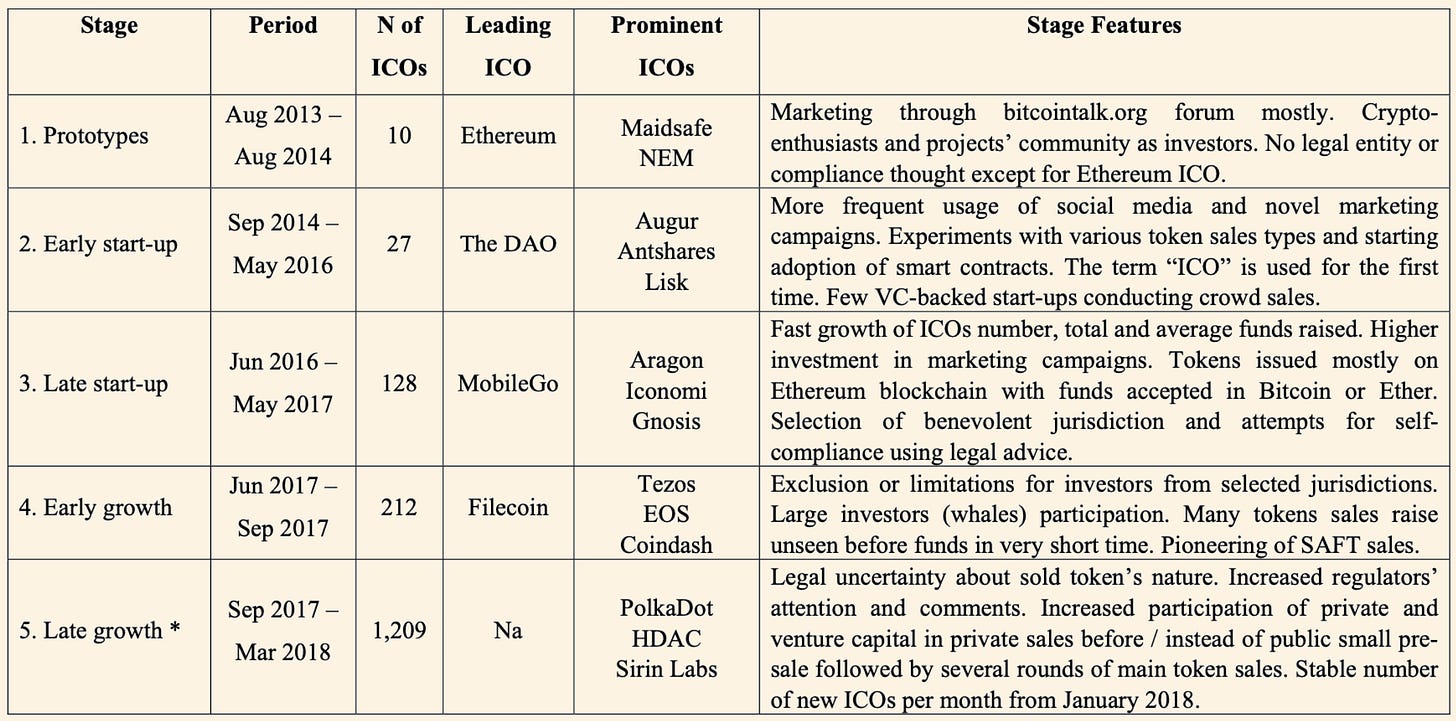

In 2017, crypto funding underwent a paradigm shift with the explosion of . What had been a VC-driven niche industry transformed as startups discovered they could raise millions from a global crowd by issuing tokens, often with only a whitepaper. The scale was unprecedented and marked a major inflection point in venture genealogy – akin to an evolutionary branch splitting off.

The numbers tell the story. In , nearly 800 ICOs collectively raised about , an impressive figure given that —a through token sales. This trend intensified in , with ICO fundraising reaching , even amid a crypto downturn. By contrast, total venture investment into blockchain companies was roughly $4 billion. Entrepreneurs recognized they could bypass traditional gatekeepers (VCs) to access crypto-enthusiast capital directly.

Structurally, tokens . Traditionally, VC funds deploy capital over ~3 years and await exits ~5–7 years later, resulting in initial negative returns that later turn positive—the J-curve. ICO-era funds saw , not years. For instance, a fund buying tokens at pre-sale often sold on exchanges shortly after launch (3–6 months). During 2017’s bull market, tokens frequently appreciated rapidly, allowing NAV spikes and , flattening the J-curve. Conversely, liquid tokens could quickly lose value during downturns, unlike relatively stable illiquid equity. Essentially, . Some crypto funds actively managed profits, resembling , while others adhered to venture-style holding strategies, sometimes adversely affected in 2018’s bear market.

The ICO surge introduced , notably (open-ended, quarterly liquidity) rather than traditional 10-year closed funds. Examples include , founded by Olaf Carlson-Wee in 2016 with VC backing and hedge fund fee structures (2% management, 30% performance). , co-founded by Naval Ravikant, was similar. They bypassed lengthy diligence, evaluating code, token economics, and community traction, using instead of traditional term sheets. Their approach merged , departing significantly from classic fund structures. Traditional LPs faced challenges adapting to this model, yet attractive early returns (often 10×+ annually) encouraged adoption, foreshadowing today's blended VC and hedge fund LP bases.

Late 2017 saw securities law concerns addressed by introducing the , inspired by Y Combinator’s SAFE equity notes. SAFTs allowed accredited investor participation in private pre-sales, complying with U.S. securities regulations by initially treating these contracts as securities. using a SAFT raised ~$257 million, becoming standard practice for token sales in 2017–2018. For VCs, SAFTs provided familiar private-funding structures, although legal clarity remains debated, especially after the SEC’s 2019 actions against issuers like Telegram. Nevertheless, , akin to Series A financing but with much earlier liquidity.

The ICO era reshaped venture norms:

The on Ethereum, raising ~$150 million before a catastrophic hack, led to a hard fork and regulatory scrutiny. The SEC’s subsequent declared DAO tokens securities, prompting projects toward SAFTs and private sales. The event underscored the importance of smart-contract security and governance, making code audits and community involvement essential for crypto VCs.

By late 2018, the ICO bubble burst; Ethereum prices fell sharply, and many ICO startups failed. Equity-based crypto funding rebounded in response, emphasizing traditional VC strengths—due diligence, governance, and long-term support—as key to surviving downturns. ICOs tested but did not replace venture capital, underscoring the continued value of professional investment support.

After the frenzy of 2017–2018, the crypto sector entered a retrenchment known as “crypto winter.” As token prices languished through 2019, many hyped projects disappeared, and regulatory scrutiny (especially by the U.S. SEC) intensified. – it refocused on quality over quantity. Total blockchain-related VC funding in 2019 remained relatively robust (around $2.7 billion across 600+ deals globally), indicating continued serious investor interest, albeit at saner valuations, often returning to equity.

This period saw the , fostering hybrid funding models:

An interesting hybrid model emerged with and , acting as venture studios rather than traditional funds. By 2020, even these players sought outside investment, reinforcing the enduring relevance of the GP/LP model.

By late 2020, early crypto venture funds reported substantial paper gains (a16z crypto fund surpassed 10× returns post-Coinbase IPO). However, volatility meant varied IRRs depending on timing. LPs evaluated metrics like , with some funds making , prompting LPs to establish new policies for digital asset custody and liquidation.

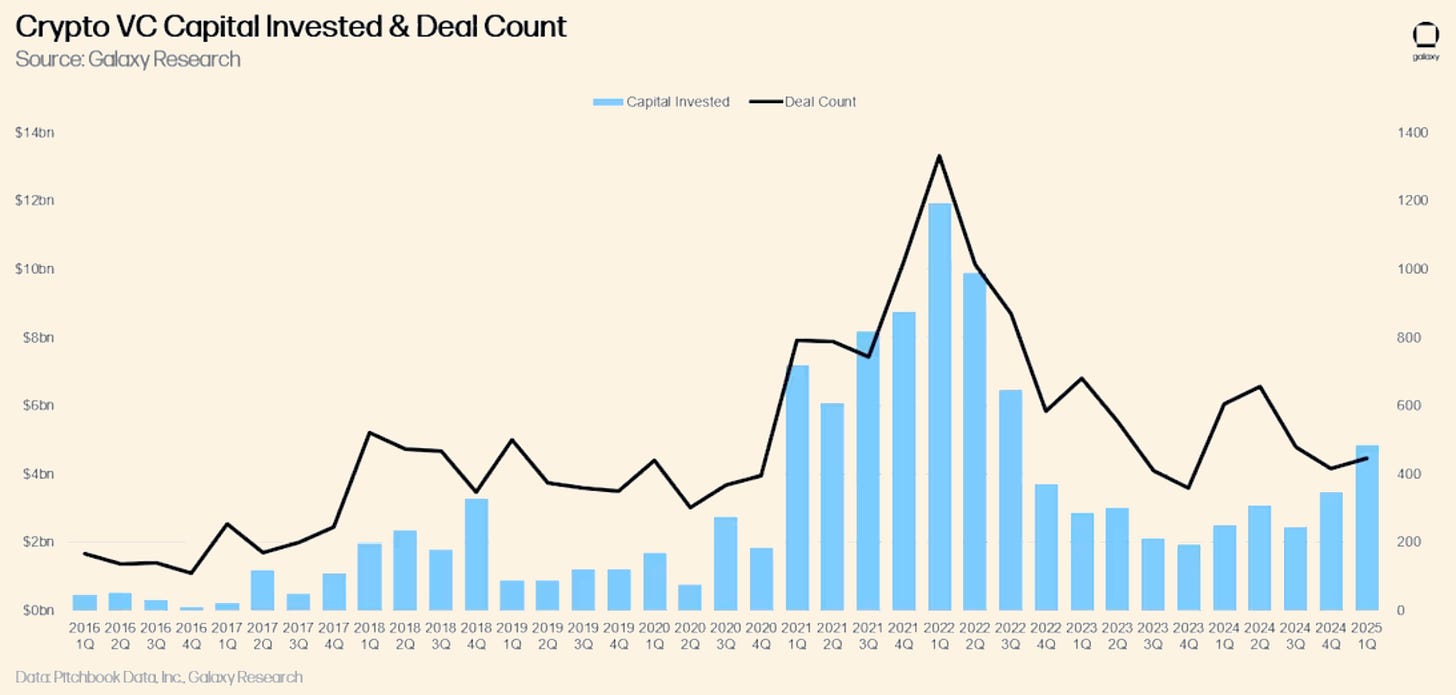

for crypto venture capital, marking crypto’s mainstream arrival in investors' eyes. Venture capitalists poured approximately , surpassing the total of all previous years combined. Remarkably, this was nearly 5% of global venture funding, extraordinary for a formerly niche sector. Deal volume also peaked, with over 2,000 rounds—double the 2020 count. This “Web3 boom” was driven by surging crypto markets (Bitcoin hitting $69k, Ethereum $4.8k), the rise of , and pandemic-era capital seeking high-growth returns. It attracted numerous , new entrants unfamiliar with crypto, significantly altering funding dynamics.

Crypto startups secured unprecedented multi-billion-dollar late-stage rounds. , established in 2019, raised a $900 million Series B at an $18 billion valuation in July, involving investors like Sequoia Capital, SoftBank, Tiger Global, Temasek, and BlackRock—then the largest private crypto round ever. Similar mega-rounds occurred for (lending), (NFTs), and (fantasy sports NFTs). Over 60 crypto unicorns emerged, up significantly from previous years, with median valuations soaring to $70 million, 141% higher than economy-wide VC deals.

Investors were motivated by FOMO, near-zero interest rates, strong crypto returns from 2020, and perceived unique Web3 upside. Prominent VC participation encouraged institutions, showcasing classic venture network-validation effects.

By the end of 2021, crypto VC merged firmly with mainstream VC. The year’s successes (OpenSea, Dapper, Solana, FTX at the time) underscored crypto’s enterprise value potential, while the resulting excesses paved the way for a necessary 2022 correction.

In 2022, the crypto venture party hit a wall. Macro headwinds and crypto-specific disasters triggered a sharp funding contraction and a return to conservative terms—a classic post-mania hangover.

Surging inflation and aggressive rate hikes battered risk assets. Bitcoin and Ethereum dropped around 75% from all-time highs, shrinking the crypto market from $3 trillion to under $1 trillion. Despite a strong Q1, crypto VC investment plunged roughly 68% in 2023 to about $10.7 billion, significantly below 2021 peaks.

These events sparked a —investors prioritized clear-utility projects with solid teams and revenue, avoiding speculative or Ponzi-like ventures.

Despite the gloom, mid-2023 saw green shoots: narratives around AI-crypto convergence, institutional ETF adoption, and real-world-asset tokenization hinted at fresh catalysts. Historically, downturn vintages often yield superior returns, prompting sophisticated LPs to urge selective yet active engagement.

The downturn : many 2021 SAFEs were repriced or converted, vesting schedules extended, and tokenomics re-engineered sustainably. Funds developed deep , paralleling private-equity capital-structure rigor.

As we step into 2024–Q2 2025, crypto venture capital finds itself on the rebound, albeit in a different form than 2021’s free-for-all. The industry has matured through adversity. Traditional and crypto-native venture practices are increasingly integrated, and investors are positioning for what they believe is the next up-cycle – whether that’s driven by new technology convergence, macro recovery, or simply the rhythm of innovation.

Following the market shake-out, crypto venture activity has shifted significantly towards the earliest stages. By 2024, about , with even many Series B/C rounds essentially supporting companies founded within the last 3–5 years. This early-stage focus arises from fewer late-stage survivors—many startups from 2017 either succeeded or exited—and a strategic emphasis on long-term bets poised to mature alongside market recovery. Galaxy Digital’s Q1 2025 research confirmed early-stage companies received most capital, highlighting robust deal flow at pre-seed and seed stages. For LPs, this signals capital deployment into long-horizon bets aligning with classic VC timelines, and smaller valuations could amplify returns if the sector revives (the vintage effect).

Many crypto funds in 2024–2025 are adapting strategically to a shifting landscape:

On-Chain DAOs & Tokenized Funds: On-chain investment DAOs (e.g., The LAO, BitDAO) and tokenized fund interests are innovative but limited in scale. These models enhance liquidity and participation, potentially evolving toward disciplined, transparent on-chain venture funding.

LP Priorities – Risk vs. Reward:

Downside Protection: Post-bear market, LPs prioritize risk management, asset custody, profit-taking strategies, and protocol risk evaluation.

Managed Liquidity: While liquidity is valued, LPs prefer GPs to strategically time exits, avoiding premature sales. Options like secondary markets and stablecoin distributions balance flexibility and protection.

Convexity (Upside Potential): Despite risks, crypto’s potential for outsized returns remains a major attraction. LPs seek skill-driven, repeatable outcomes, favoring clearly articulated scenarios (bull, base, bear) and diversified thematic portfolios.

Allocating Across the Crypto Spectrum:

CIOs now choose from:

Traditional VCs with occasional crypto exposure.

Hybrid firms (e.g., a16z, Paradigm) balancing crypto and equity investments.

Crypto-native venture funds with varied stages and strategies.

Liquid crypto vehicles (ETFs, hedge funds).

Institutional investors increasingly see crypto as essential within alternative asset strategies, typically allocating cautiously (initially 1–2%), balancing exposure and uncertainty.

insights4.vc and its newsletter provide research and information for educational purposes only and should not be taken as any form of professional advice. We do not advocate for any investment actions, including buying, selling, or holding digital assets.

The content reflects only the writer's views and not financial advice. Please conduct your own due diligence before engaging with cryptocurrencies, DeFi, NFTs, Web 3 or related technologies, as they carry high risks and values can fluctuate significantly.

Note: This research paper is not sponsored by any of the mentioned companies.