Tana Delta farmers fear for future harvests as saltwater creeps inland

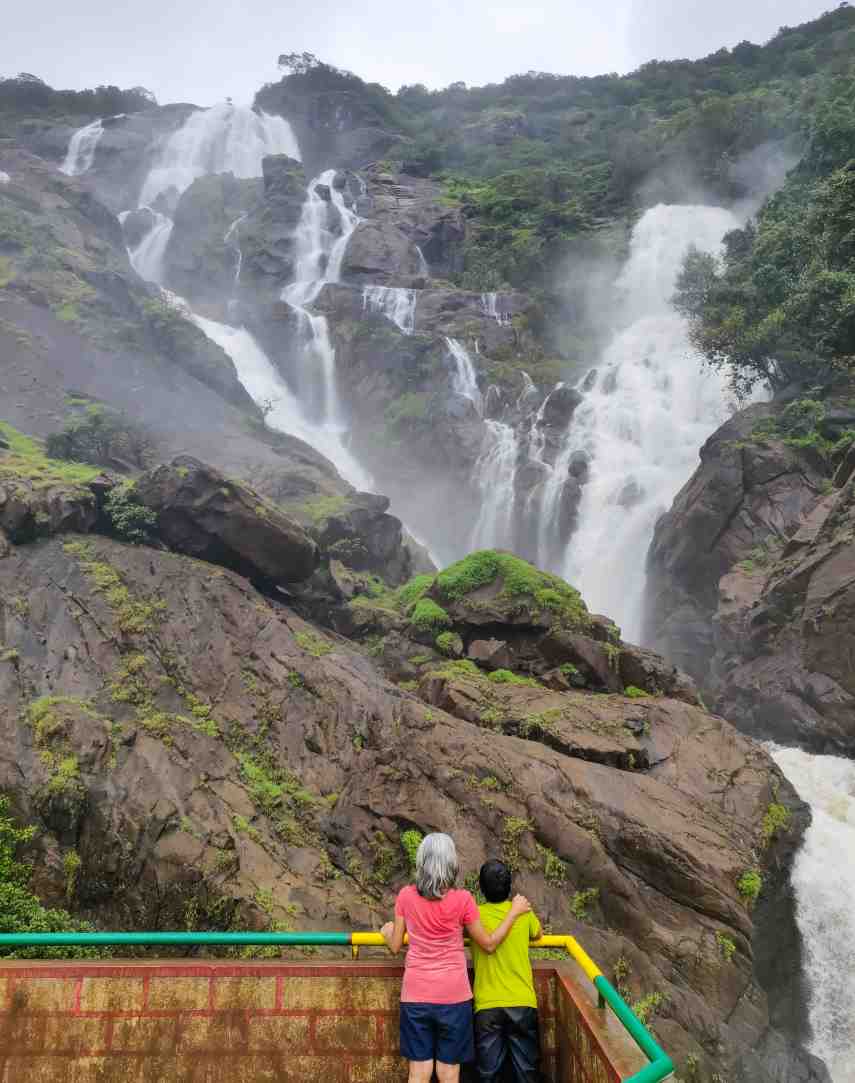

In an ordinary July, the air in Tana River County’s Ozi area is thick and humid, with rice paddies swaying to the breeze from the Indian Ocean.

The wind carries a subtle salty tang that settles at the back of the throat, a taste farmers like Asha Katana know all too well.

In her early 30s, Katana understands the delicate balance between the ocean’s salty water and fresh water, a balance that shapes the agricultural productivity of the villages along the coastline.

“It’s the rainy season now, and water from the Tana River stays fresh all the way to its mouth, where it meets the Indian Ocean at Kipini.

Other times, when the river’s volume drops, the water turns salty because the ocean starts pushing inland,” Katana explains. This phenomenon, known as seawater intrusion, is increasingly becoming a silent threat to communities living along the coast.

In productive villages like Ozi, where most residents are farmers who depend on the Tana River for fresh water, climate change has made access to this vital resource even harder. Although farmers like Katana work relentlessly on their once thriving rice fields irrigated by the river, each harvest has continued to shrink as salty water from the sea keeps pushing inland.

“A lot of changes are happening at the Coast. With the frequent droughts we have seen in recent years, communities living downstream and depending on Tana River are the hardest hit,” said Nyara, a resident.

Nyara explains that when the water turns salty, livestock cannot drink it, freshwater fish die and crops fail.

Salty water intrusion happens when water levels in the Tana River drop too low to push back the ocean’s salty water, which then flows inland through the riverbed. Current studies show that seawater intrusion has been recorded up to 30 kilometres inland.

Each year, communities living downstream along the Tana River continue to face salty water moving further inland, especially during frequent and severe droughts. “We travel many kilometres in search of fresh water, yet we’re surrounded by so much water,” says Nyara.

It’s not only farming communities who are battling the changing environment, marked by rising sea levels and saltwater intrusion. Pastoralists and fishermen living within the Tana Delta are also struggling to cope.

Moses Jaoko, a fisherman, says that whenever the water turns salty, many fish die along the Tana River.

“Fishing is becoming unsustainable, especially if big developments are built upstream without considering how freshwater fish will survive. It’s worrying when fish die like that,” Jaoko said.

In 2020, more than 1,000 fish of different species died along the Tana River within the Tana Delta due to seawater intrusion. The incident happened after communities tried to block salty water from flowing inland at Matomba Brook.

Stay informed. Subscribe to our newsletter

For years, the Tana River has been the backbone of the country’s largest delta, supporting agriculture and thousands of people who depend on its fresh water.

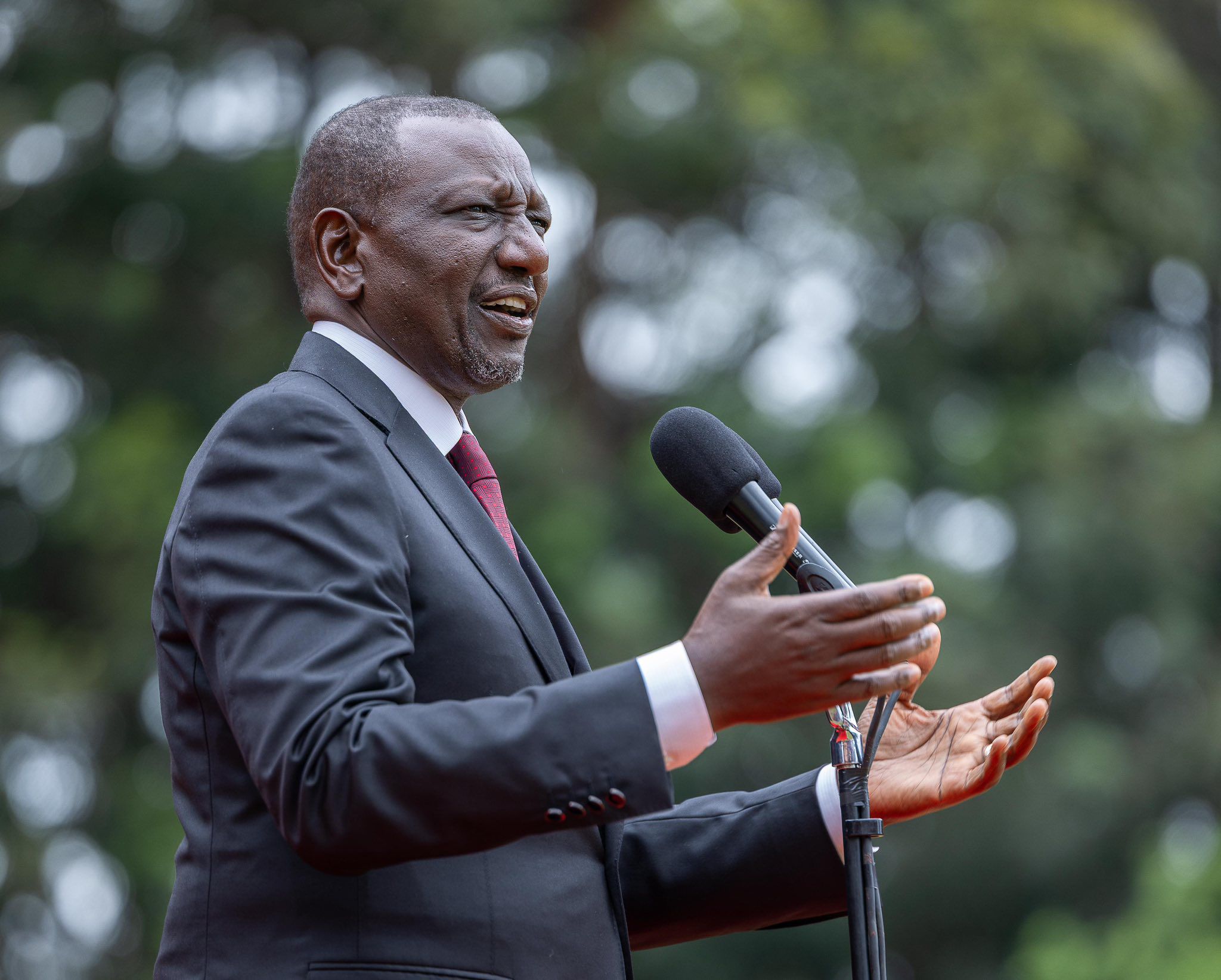

The Tana River is also a lifeline to the Seven Forks Hydro Scheme, a series of five hydroelectric power stations that include Masinga, Kamburu, Gitaru, Kindaruma and Kiambere.It also supports large irrigation schemes, such as the Tana and Athi River Development Authority (TARDA). Several Vision 2030 flagship projects, including the Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport Corridor (LAPSSET), the Tana Delta Irrigation project and the High Grand Falls Dam, are also in the pipeline.

The High Grand Falls is projected to generate 700 megawatts of hydro power while irrigating more than 250,000 hectares of farmland.

According to GlobalData, which tracks and profiles power plants worldwide, the project is currently at the permitting stage.

It will be developed in multiple phases and is projected to commence in 2028 and enter into commercial operation in 2031.

The dam is a flagship project under Kenya Vision 2030, supported by the UK’s Partnership for Accelerated Climate Transition (UK PACT).

But communities living downstream, along with local leaders, policymakers and environmental experts, now worry that the many developments planned along the Tana River will put even more pressure on an already strained resource.

In his late 70s, Abdallah Islam is one such concerned resident. He has been at the forefront of raising awareness, seeking meetings and writing letters to policymakers about their plight.

“The Tana Delta is changing. It’s no longer the delta we knew. The seawater is pushing upstream so fast. These are new changes that never existed before, and we need to talk about them,” Islam said. Islam is part of the Tana Delta Conservation Network, an umbrella body representing 106 environmental conservation groups across the Tana Delta.

The network has written to the Tana River County Government, expressing concern that the proposed dam will heavily impact their activities, including farming, grazing and fishing.“We did not attend any public participation forum. If we keep quiet and allow development projects to continue without considering downstream communities, the Tana Delta will eventually choke from uncontrolled upstream activities,” Islam warned.

Experts are also worried that the massive developments coming up along the Tana River could worsen an already dire situation.

“If these big developments continue without strong environmental safeguards, what will happen to communities already suffering from salty water intrusion? What will happen to the Tana Delta, which is a breadbasket for thousands?” asks Dr Paul Matiku, Director of Nature Kenya.

Dr Caroline Ng’weno, a policy expert, also stressed the need to revise the Environmental and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) to include input from downstream communities and to implement a fair, balanced water management plan.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1285617372-abe7aa8ae9e4436a9a0d12393ff7aa52.jpg)