Name a Stephen King character, without checking a bookshelf or Google. Perhaps Jack Torrance springs to mind, if you also happen to be a blocked writer, or the eponymous Carrie—although, can you remember her last name? For all his stature as a beloved bestselling novelist, King doesn’t have a Humbert Humbert or a Hercule Poirot, a Huckleberry Finn or a Captain Ahab—an iconic character, the kind who becomes a byword for a type or personality or dysfunction. Not, that is, until Holly Gibney came along. If Holly isn’t in Captain Ahab’s rank yet, give her time. Only a fool would count her out.

Holly entered the King multiverse in 2014, with the publication of King’s first straightforward crime novel, Mr. Mercedes. That book is the story of a retired police detective named Bill Hodges, who’s harassed by the perpetrator of the worst case he ever failed to solve: the random mass killing of a crowd of job seekers, mowed down by the titular automobile. Bill Hodges may be the main character in Mr. Mercedes and the two novels that followed it, but as King himself told Terry Gross of Fresh Air, Holly Gibney “just walked on” in Mr. Mercedes and “more or less stole the book. And she stole my heart.” With the publication of Never Flinch, King’s latest novel, the amount of bookshelf space the author has devoted to Holly has rivaled that of Roland Deschain of the 8-volume Dark Tower series, an archetypal gunslinger who pursues the equally archetypal Man in Black across the perilous wastelands of an epic fantasy world.

Holly is no archetype, however. She is the flower of King’s late career and his forays into crime fiction. Occasionally, she reckons with an otherworldly evil, as she does in 2018’s The Outsider, but she’s more likely to find herself tracking down merely human monsters, as she did in 2023’s Holly, in which a client whose daughter has gone missing contacts Holly’s private detective agency, Finders Keepers, for help. True, Bonnie Dahl’s fate is remarkably grisly, even for a Stephen King character’s; she is captured and devoured by a pair of cannibal college professors who have convinced themselves that human flesh will fend off old age. But the novel makes it pretty clear that the couple is deluding themselves about the salutary effects of their horrific version of keto. Similarly, while Never Flinch features not one but two homicidal lunatics, neither of them possesses (or is possessed by) forces beyond our ken.

When Holly first walked into Bill Hodges’ life, she was a meek and rather peculiar woman in her 40s and completely under the thumb of Charlotte, her controlling and critical mother. In Holly, she learns that her mother has concealed an inheritance from her that would have made the rocky early years of the Finders Keepers agency much more stable. Charlotte did this presumably in the hope that Holly’s bid for independence would fail. Destructive parenting has been a King theme going all the way back to his first novel, the aforementioned Carrie, published in 1974. In Never Flinch, both Holly and one of the novel’s two villains hear the judgmental voice of a dead parent at moments of stress. The difference between good and evil is learning how not to listen to it. The bad guy in Never Flinch even goes full Gollum at the novel’s climax, arguing with himself by alternating between mimicry of his own voice as a child and that of his abusive father. “You aren’t doing anything,” the internalized father tells him, calling him “Mr. Useless” and a “worthless fucking flincher.” (The novel’s title comes from a demand the killer’s father made while flicking hockey pucks at his son.)

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

Charlotte insisted that Holly’s obsessive-compulsive disorder made her too emotionally fragile to live on her own. Bill Hodges, who becomes a surrogate parent to her, initially writes off the tremulous, mumbling Holly as someone who “doesn’t have a damn thing going for her … not a single scrap of wit, not a single wile,” although King adds that Bill “will come to regret this misperception.” When he sees mother and daughter together, they look to him less like a parent and child than “like a matron escorting a prisoner—probably a drug addict—into county lockup.” When Bill’s client, who is Holly’s cousin, is killed by a car bomb intended for Bill, she becomes drawn into Bill’s investigation of the crime, revealing an expertise with computers that proves invaluable. By the end of the novel, Holly is clubbing the bad guy on the head with Bill’s “Happy Slapper”—a sock filled with ball bearings—to protect her friends.

In the books that followed, first as Bill’s sidekick, then later—after Bill’s death—on her own as the head of Finders Keepers, Holly blossoms, sort of. She remains mousy in appearance, which suits her just fine. Now in her 50s, Holly is, according to Never Flinch, “small and graying, rather plain in the face but well-groomed,” and with “a talent for being slightly dim”—that is, able to go unnoticed. She achieves this even in her fictional hometown of Buckeye City, Ohio—i.e., Cleveland, as Derry, Maine, is King’s version of Bangor—where she has figured in several spectacularly gruesome cases.

Holly loves coffee, enjoys Colleen Hoover novels, and hates insurance companies, even though they often hire her. She wears “stylish” but “sensible” shoes. To her delight, she has a cozy little apartment of her own and no desire to leave flyover country, which King depicts with a loving familiarity, as he does so many nondescript and unglamorous working-class haunts. King’s crime fiction may lack the clockwork construction and procedural exactitude of the great detective novelists—Holly’s friends compare her to Sherlock Holmes, but most of her solves come from flashes of intuition, and in Never Flinch it takes her far too long to make a significant connection—but he has no rival when it comes to evoking a sense of place. He may not do misdirection, but no one can capture a church-basement AA meeting, or two drunks hanging out behind a laundromat enjoying the warmth of the heating vent, with more genuine, uncondescending affection.

The pandemic, and the OCD anxieties it activated, made Holly’s P.I. work more challenging—Holly features scene after scene of its heroine assessing the potential contagions in every encounter. It also claimed the life of her anti-vaxxer mother. Yet by Never Flinch, Holly has become more than competent, agreeing to a bodyguard gig with a firebrand feminist on a lecture tour while, on the side, helping a friend in the Buckeye City police track down a serial killer.

Holly is, in a way, the quintessential King protagonist: an ordinary (albeit quirky), unprepossessing person who, in the clutch, discovers untapped reserves of smarts and, most important of all, courage. Her antagonists in each book may be florid madmen and malevolent spirits, but in the overarching narrative of her series, the real Big Bad is the self-doubt instilled in her by her mother. At 5-foot-3, Holly makes for an unlikely bodyguard for Kate McKay and her assistant in Never Flinch, although Holly does manage to save Kate’s life on more than one occasion. Nevertheless, she still dreams of her mother whispering, “The idea that you can protect those women is ridiculous. You couldn’t even remember your library book when you got off the bus”—a rare incident of forgetfulness from Holly’s childhood that comes up over and over again. Defeating an evil clown who lives in the sewer system is a piece of cake compared to erasing the insecurities written onto us in our early years.

King’s fiction is, of course, full of darkness, whether it’s the nihilistic narcissism of Mr. Mercedes or the grotesque selfishness of those demented college professors in Holly. In Never Flinch, the ultimate culprits are two old King boogeymen: religious fanaticism and addiction. One of the novel’s maniacs is hell-bent on assassinating Kate for her pro-choice rabble-rousing, and the other, while claiming to be a pursuer of justice, simply discovers that he gets a kick out of killing random victims. In King’s earlier works, individual fortitude was enough to defeat such forces, but a key distinction of the Holly Gibney series is that its heroine inevitably requires a little help from her friends.

Foremost among these are Jerome and Barbara Robinson, the son and daughter of Bill’s Black neighbors and in time Holly’s own surrogate niece and nephew. The siblings are kids when first introduced in Mr. Mercedes, and by Never Flinch are in their 20s. Much of Holly and Never Flinch is taken up with developments in Jerome and Barbara’s lives that feel tangential to the main plot, even if they do tie into it eventually. There’s an avuncular fondness to these passages. Truth be told, Barbara and Jerome aren’t very convincing as 21st-century zoomers, but what they do resemble is the rosy vision of a young person as seen by a doting older relative or mentor. Somehow this works. Holly’s pleasure at seeing Jerome publish a book and Barbara get the chance to join the backup singers for an Aretha Franklin–like soul legend is infectious. In turn, they regard Holly and her many eccentricities as very dear.

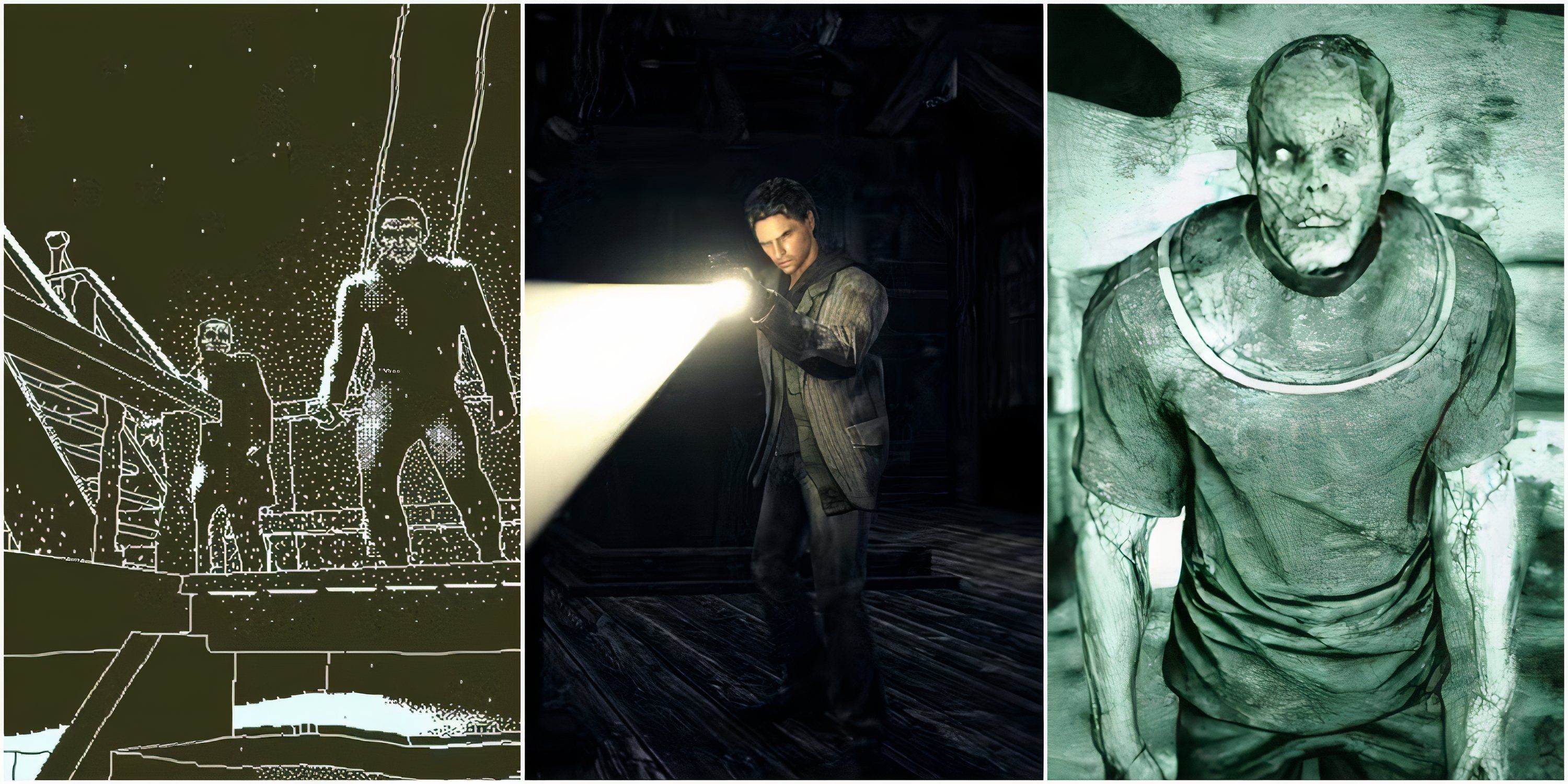

Holly has been depicted onscreen twice: In David E. Kelley’s series Mr. Mercedes by Justine Lupe (best known as Willa from Succession) and in The Outsider by a riveting Cynthia Erivo. The latter series, created for HBO by Richard Price, took many liberties with King’s novel, transforming Holly into a neurodivergent savant. It’s a superior work of art to Mr. Mercedes, one that captures the dread and sorrow of King’s fiction better than Kelley’s campier adaptation. Price’s Holly, however is a lonelier character than Kelley’s, and loneliness is not Holly’s problem.

Community is what makes King’s Holly Gibney novels a surprisingly sunny foray for the venerable horror master, despite the nightmarish opponents she confronts. Holly’s true opposite in Never Flinch is Kate McKay, who has charisma and the right politics but also the oblivious self-absorption of those who are famous and believe they deserve it. Holly knows that each of her triumphs is, at heart, a group effort. Her place in the world may be modest, but it is nonetheless enviably secure and nourishing. “I wish she were a real person and that she were my friend,” King told Terry Gross in that same interview. Give her a few more books, and millions of readers will agree with him.

Get the best of movies, TV, books, music, and more.