'Spitfires' is a soaring look at female flyers, including a legend from LI

Former Newsday journalist Becky Aikman’s new book deals with aviation, but its tales are of brave women pilots are no flights of fancy. In (Bloomsbury, $31.99), Aikman uncovers the hidden history of female aviators who flew perilous missions in Europe.

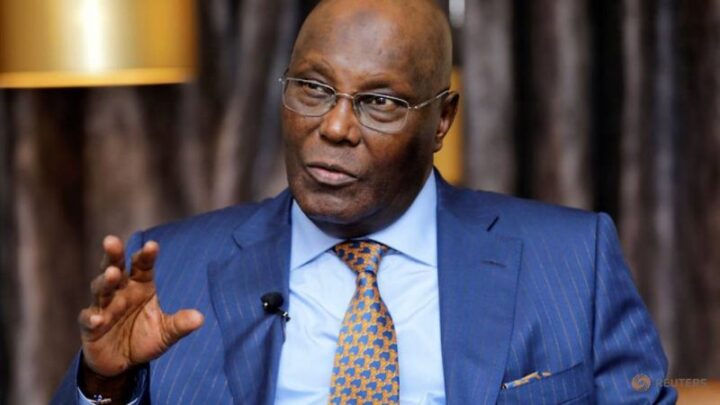

Former Newsday reporter Becky Aikman is the author of “Spitfires.” Credit: Elena Seibert

The acclaimed author spoke by phone from her New York apartment about Long Island’s aviation history, the freedom of flight and the delight of reading old diaries.

I found this story thanks to my mother. I was talking to her about how I would like to write a book about people who did something extraordinary and yet unknown to the public. Without a pause, she told me to look into the American women who flew for England’s Air Transport Auxiliary in World War II. These women were completely forgotten by history even though they were well known at the time. The more I learned, the more excited I became about the project. At one point, an elderly gentleman helping me at a museum said, “I hope you don’t plan to fictionalize this, because nothing could be as glamorous as the reality.” He was so right.

These 25 American women did some of the most dangerous flying work of the war. They were pilots before World War II and wanted to serve, but the U.S. would not accept women to fly. Great Britain, meanwhile, was under constant attack and desperate for help, so they formed a unit made up of injured Brits, men from foreign countries and even women. This group transferred aircraft between bases. They often had to fly untested aircraft rolling off manufacturing lines that frequently failed in the air.

These women were also transporting badly damaged aircraft riddled with bullet holes from the front lines to be repaired and these often crashed. In addition, the pilots faced the English weather, which was quite variable. They flew without using instruments and often could not see because of fog or storms. They had to be extremely skillful to get out of these situations.

"Spitfires: The American Women Who Flew in the Face of Danger During World War II" is a new book by Becky Aikman. Credit: Bloomsbury Publishing

Several of the women used Roosevelt Airfield as their homebase before the war. Some flew for pleasure and others worked there as flight instructors. Jackie Cochran was a famous aviator who flew out of the Aviation Country Club of Long Island, which was for very tony people. She never fit in because she came from a poor background, but she was driven. Winnie Pierce was a salesperson and took people up to demonstrate the aircraft. Once, she spotted a house fire on Long Island while flying and she famously dove repeatedly over the house to guide the firetrucks toward the fire.

I had to track down the families of the women in order to learn about them. For example, I tracked down Winnie Pierce’s son, who was thrilled to talk about his mother. He’d saved his mother’s diaries in his attic because he always wanted her to be recognized for this. He sent me her diaries and they were stunning, so full of emotion and excitement, so candid. I was able to find quite a few diaries and they gave me information about piloting planes as well as their inner lives.

The pilots came from all parts of American society. Some were crop dusters, some were debutantes, but it didn't matter who they were before. Far from home in the middle of a war, they got to reinvent themselves. A debutante who was expected to marry a wealthy man got to live the life she preferred. And some of the pilots from the least privileged backgrounds made their way into British society.

Newsday: What freedoms did flight afford these women that readers in 2025 might not understand?

Aikman: It was very unusual for a woman to have her pilot's license back then; many women did not even have a driver’s license for a car. People were often drawn to flying for the freedom it afforded — the freedom to be who they wanted to be, up in the air alone, having an adventure and not being restricted by any of the rules and traditions of society that told them what to do.

Newsday: How does this work differ from the work you did as a Newsday journalist?

Aikman: A lot of the work is similar, just more detailed and a lot more to keep in my head. As a reporter, I’m accustomed to picking up the phone and talking to people. With this book, many people are no longer alive, so I needed to use secondary sources, archives, and secondhand accounts. This kind of research takes much longer. The book took five years to write, from start to finish.

Newsday: Do you fly?

Aikman: No, I do not. And the fact is, I am not a brave person and I can’t imagine that I could’ve done what they did.

Newsday: Do you have a favorite character?

Aikman: I can’t! Honestly, I knew them all so well by the time I was finished writing. I had empathy for everyone. Readers have told me how attached they become to these characters and I felt the same. When I wrote the last page, I just thought: I am going to miss them so much.