Sorry, Baby Review - A New Seminal Work in the Trauma Recovery Canon

We don’t talk enough about trauma.

Or, rather, we don’t talk enough about trauma’s complexities. It’s difficult to capture the nuances, contradictions, and absurdities that accompany a violent, disruptive act in everyday life, let alone a two-hour film that must also consider plot, setting, characters, history, and other storytelling conventions. So, when we do talk about trauma in a storytelling context, we tend to shortchange its journey. We condense the fits and starts, highs and lows, into an easily digestible format that, despite even the best of intentions, can feel at least incomplete, if not outright dishonest.

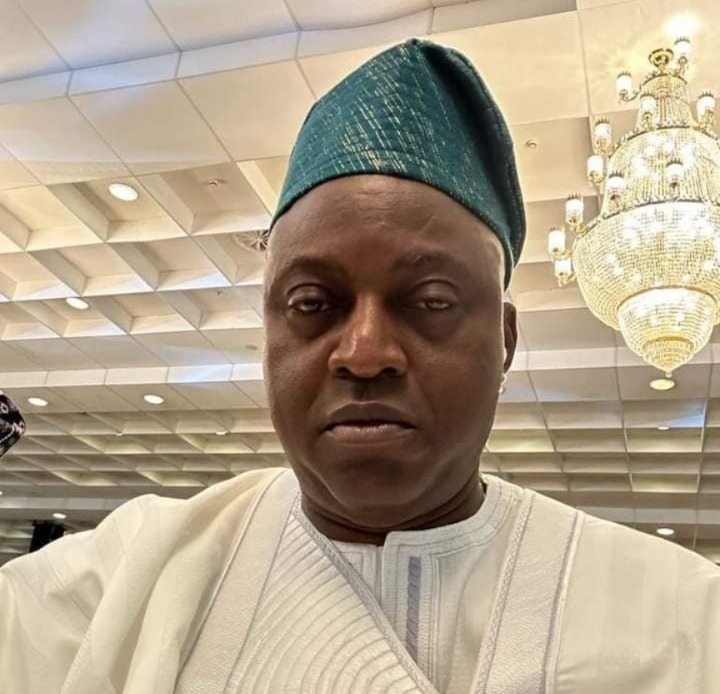

Eva Victor appears in Sorry, Baby by Eva Victor, an official selection of the 2025 Sundance Film Festival. Courtesy of Sundance Institute | photo by Mia Cioffy Henry.

⛶

⛶

⛶

It isn’t fair to ask someone to correct nearly a century of cinematic precedent, but that doesn’t mean Eva Victor can’t try. In Sorry, Baby, her first feature film, she plays Agnes, an English professor at a Northeast college who is visited by her best friend Liddy (Naomi Ackie). It’d been some time since they’d last seen each other, and Liddy is excited to reconnect with her best friend over exciting developments in her life, like her pregnancy.

Even with their easy rapport grounded in dry, awkward humor, Victor hints that Agnes herself is in some sort of suspended animation. Their laughter is intercut with moments of foreboding stillness, and despite their physical closeness, Victor frames them from a distance, surrounding them with empty space. Agnes may not be outwardly unhappy, but something painful is in the periphery, just out of sight, hanging over her and our heads.

An awkward reunion with Agnes and Liddy’s graduate classmates all but confirms it when a jealous colleague not-so-casually mentions their thesis advisor, Preston Decker (Louis Cancelmi). Decker is also the man who sexually assaulted Agnes, a devastating incident that has dimmed her light enough for Liddy to beg her to “please don’t die.”

Agnes insists that she won’t, joking that if she wanted to die, she would’ve died the year it happened, or the year after it happened, or the year after that year. It’s a heartbreaking moment, but, as Victor will demonstrate through the rest of the film, it still hits several grace notes of levity without feeling disrespectful or off-putting. It also reflects how trauma recovery is a process that you can’t necessarily trust; it will ebb and flow of its own accord, surprising in how, where, and when it’ll manifest.

Victor leans into this idea more explicitly by framing Sorry, Baby as a series of vignettes to detail Agnes’s journey. We see Agnes in the hours before the assault, where we get to see who she was before Decker violently upended her life. It’s a relatively short collection of scenes, but Victor crafts a complex portrait of a young woman whose dry humor and subtle charm suggest a confidence she doesn’t quite possess.

With us knowing that an assault is about to take place, Victor succeeds in depicting the sickening circumstances (such as Decker’s subtle efforts to make Agnes feel seen) while also showing how Agnes could have missed those signals as she established a fruitful mentorship with someone she thought she could trust. It makes the assault itself — only depicted by a series of time-elapsed wide shots of Decker’s house — all the more devastating.

Victor achieves something even trickier in the assault’s immediate aftermath: reclaiming the levity. She achieves this by leaning into Agnes’s dry humor and the absurd failures of the systems meant to hold sex criminals accountable. We get glimpses of Agnes’s deadpan personality peeking through her brutal recount of her assault to Liddy in the bathtub, grounded in her trying to determine the assault’s extent and validity.

Even with those glimpses, Victor ensures that Liddy affirms Agnes’s trauma at every step. That affirmation is critical when Agnes pursues medical support and legal consequences. She gets genuine laughs out of Liddy’s disgust at a male doctor’s insensitive bedside manner and the college’s inability to punish Decker for his crime. (The college representative can only offer a painfully awkward “We are women” statement of solidarity.) What’s key to the film’s humor is that it’s never at the expense of Agnes or the assault. While the systemic responses to her assault are worthy of scrutiny and ridicule, Victor regards Agnes’s attack with deep, genuine care.

That care extends to Agnes’s recovery, which encompasses the film’s remaining vignettes. Victor keenly understands that recovery isn’t a straight path, and she brilliantly taps into its inconsistencies through Agnes’s multi-year journey. It can be hilarious, like when Agnes’s cat brings a rat into her bed and she bashes its head in, which somehow manages to unlock her ability to enjoy sex with her neighbor, Gavin (Lucas Hedges).

It can also be gutting, like Agnes explaining during jury duty selection for another case that she doesn’t want Decker prosecuted because of his daughter. Whichever way Agnes’s triggers swing, deep authenticity and honesty accompany them, bolstered by Victor’s confident direction, staggering for a first-time feature. She handles her story’s tonal shifts beautifully and ensures that, even in the hyper-specificity of Agnes’s experience, the audience can connect with it.

Victor rounds out her renaissance in filmmaking with a funny, sensitive, and deeply felt performance. She has a quiet but affecting screen presence, communicated through subtle glances and expressions in the background of her charming line deliveries. She doesn’t quite wear her heart on her sleeve, nor does she need to, but her sleeve is opaque enough that you never lose sight of it. When Victor lays Agnes’s pain bare, it is soul-crushing.

Her blank, exposed stare on Agnes’s drive home from Decker’s house is one of the year’s most haunted, devastating scenes, and a hallmark amongst this year’s most vulnerable work. Naomi Ackie is a brilliant complement as Liddy, bursting with joy when she first arrives on screen and providing a steady beat of tender care and ferocious support as Agnes grapples with the short- and long-term effects of her assault.

While the last quarter-century has spurred more artistic explorations of trauma, they tend to be restricted and limited in scope. Sorry, Baby is a powerful and successful expansion effort, helmed by an artist whose storytelling command is remarkable for any filmmaker, let alone a first-timer. Hers is a powerful affirmation that recovering from debilitating trauma has no proper timeline or checklist to complete.

It will likely be messy, counterintuitive, and even inappropriate for traditional definitions of taste. However, that doesn’t mean you stop trying. Trying is a win in its own right, and the one that ultimately matters most. That takeaway is more than enough to qualify Sorry, Baby as a new seminal work in the trauma recovery canon.