Some Day We'll Look Back on This and It Will All Seem Funny

Tomorrow, Bruce Springsteen is releasing TRACKS II: THE LOST ALBUMS, a collection of seven previously unreleased albums recorded between 1983 and 2018. If this were an earlier time in my life, you’d find me anxiously waiting outside the record store, eager to get my hands on Bruce’s new album the moment the store opened. I can still remember where I bought every Bruce record from Darkness on the Edge of Town to The Rising. Rushing home. Dropping the needle (or inserting the CD). Studying the lyrics and cover art. And playing the albums over and over till they etched a groove in my soul.

Where did this devotion come from? It all started with a blank cassette tape that I popped into my portable Panasonic AM/FM recorder one Tuesday night in September, 1978. I positioned the tape player atop an Adidas shoebox on the floor of my Long Island bedroom, and tuned the dial and antenna to WNEW-FM (102.7—“Where Rock Lives!”) to record Bruce’s concert from the Capitol Theatre in Passaic, New Jersey.

When he and the E Street Band took the stage, I pressed the Play/Record buttons, and over the next three and a half hours (and two additional cassettes), the tape player arranged magnetic particles on those blank tapes to capture the blueprint for my teenage identity.

My first introduction to Bruce had been two years earlier, at 13, when I was gifted Born to Run as a bar-mitzvah present from a high school girl who used to babysit me. “It’s this new guy, Bruce Springsteen,” she said. But this radio broadcast was my first time hearing him play live.

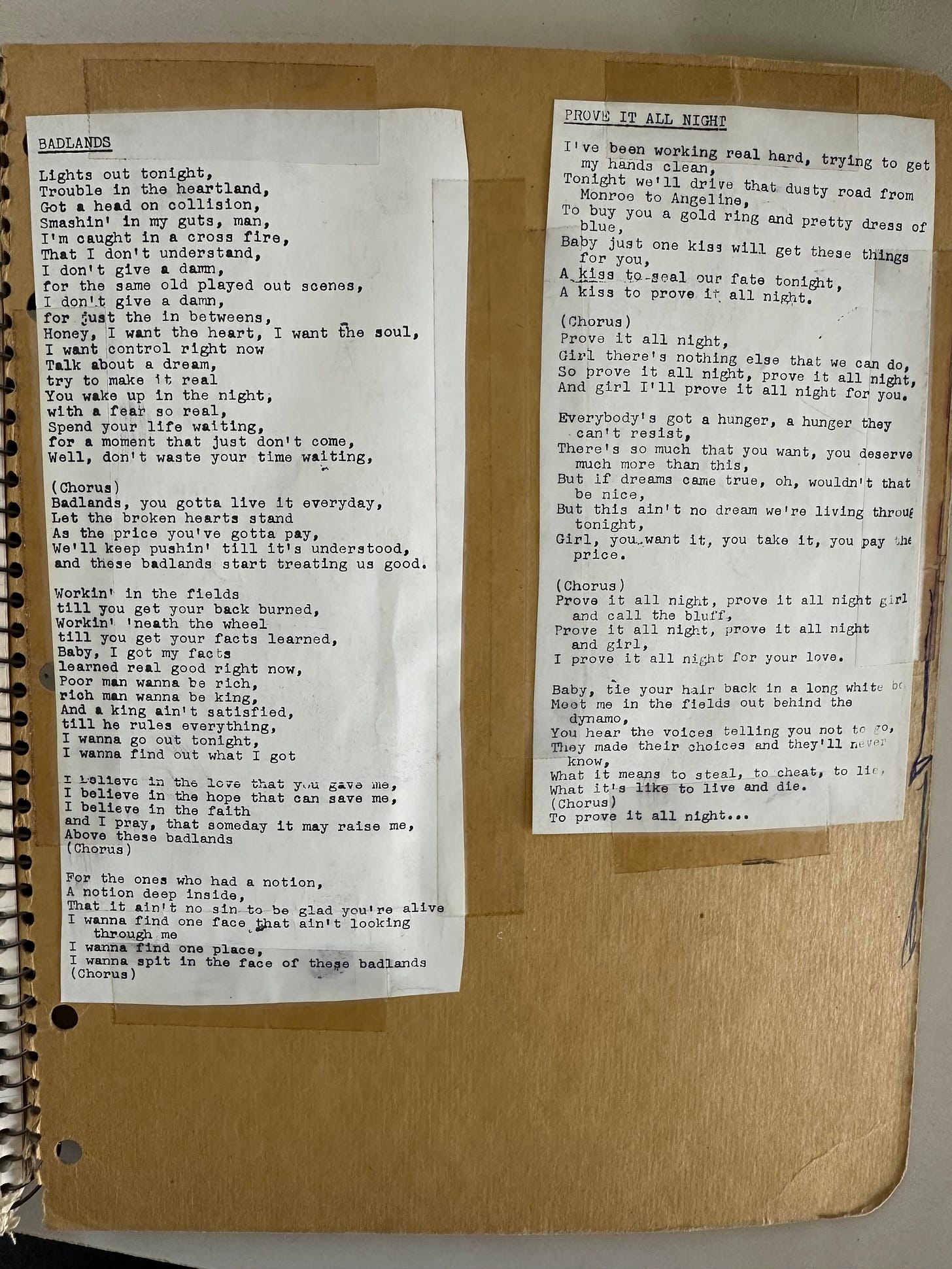

Three sustained opening chords, and then Bruce asked, “Are you ready?” The crowd roared, and the band launched into “Badlands.” I could feel his presence coming through the tiny speaker—a raw, evocative voice singing with lay-it-all-on-the-line conviction, bringing new depth to songs I had only heard on the studio albums. Listening to that show blasted open my adolescent heart chakra, igniting a hunger for a life of intense feeling, unbridled freedom, wild romance, and unbreakable bonds. Visions of driving down a highway, best girl by my side, danced in my head.

But it wasn’t just the music. It was the way he owned the crowd. The spoken introductions and dedications. His ability to express the darkness and despair of a world gone wrong—and the joy of transcending it. There was a spiritual revival happening in Passaic, and I desperately wanted to be under that tent. Around the 45-minute mark, I crouched like a cat, ready to pounce as the cassette’s first side ended, flipping it over in seconds so I wouldn’t miss a single note.

By the last encore, Bruce had become my de facto cooler older brother. I wanted to feel as alive as he sounded. I wanted to be that cool, confident, and commanding.

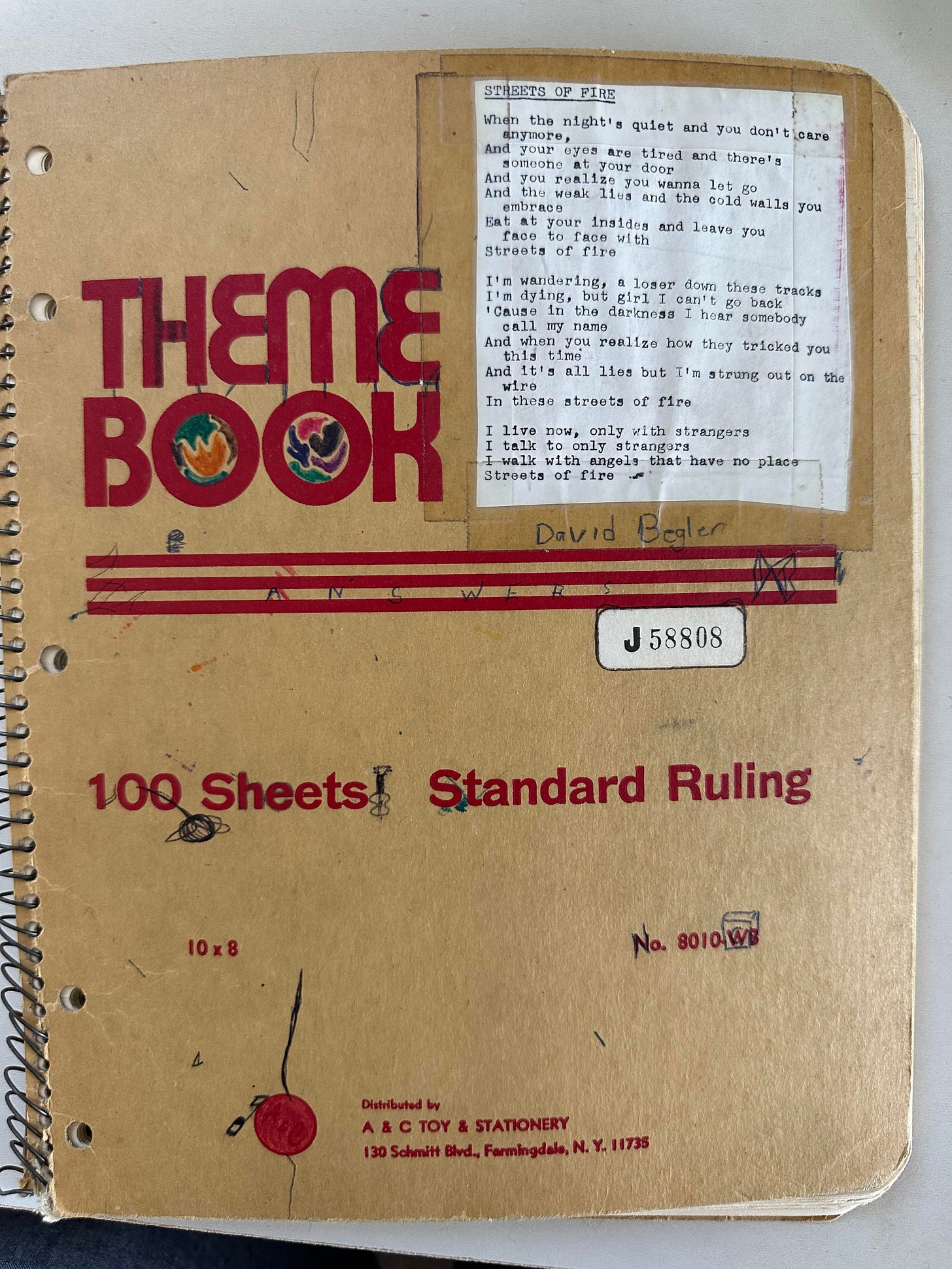

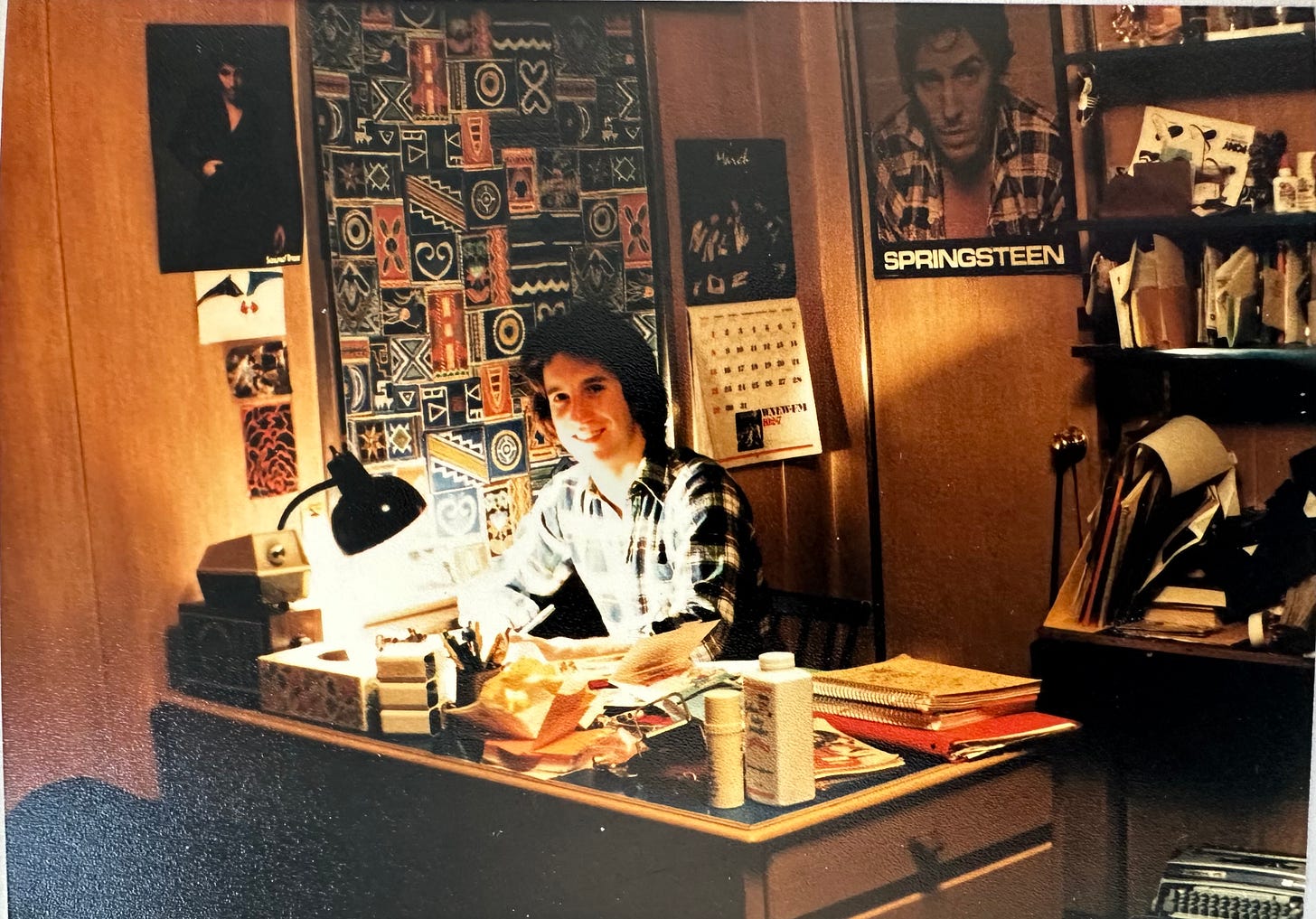

So I plastered Bruce posters across my bedroom walls. I cut up the lyrics insert from Darkness on the Edge of Town and taped the songs into my journal. I etched the words “Thunder Road”—the opening track to his 1975 record, Born to Run—on my high school locker. And even wrote out the song’s lyrics on a sheet of loose-leaf paper, folded it into quarters, and tucked it in my wallet—like carrying it on my person might somehow shape me into the person I dreamed of becoming. But what I really craved was to hear more live Springsteen, where the songs took on a deeper resonance.

Then I found out there were these things called “bootlegs.” A friend lent me an illicit album called “You Can Trust Your Car To The Man Who Wears the Star”—a 1975 recording from the Main Point in Pennsylvania. The cover showed a crude sketch of Bruce with a shit-eating grin, wearing a Texaco cap. One track, “Wings for Wheels,” was an early version of “Thunder Road”—but it was Angelina’s dress that swayed, not Mary’s. Different lyrics. New clues. More revelations.

The hunt for more bootlegs began. My friend Matt and I took the LIRR into Manhattan, then the subway down to Sullivan Street Records in the Village. Ask the guy at the register about bootlegs and he’d flat out deny they had any. They were illegal to sell. But in the back of the shop was an unlabeled bin of hidden contraband. I laid down twenty bucks like it was a street drug deal and bought a red vinyl bootleg called Fire on the Fingertips.

I got my hands on more bootlegged shows from legendary venues. The Winterland. The Roxy. The Bottom Line. They were treasure maps to a mythical place I formed in my mind: an emotionally intense, high-stakes world of adulthood where dreams were found and lost.

As a 15-year-old middle-class kid from Long Island, I had zero experience with working-class struggles, street hustlers, fast cars, or the mysteries of the night. I wasn’t from the Jersey Shore or a blue-collar family, but I was close enough—Long Island had boardwalks and beaches. New York City was a train ride away. Bruce’s music told me there was some promised land waiting for me beyond the confines of my suburban bedroom. A place where all my self-doubt would disappear and I’d exist comfortably in my own skin.

My brother thinks Bruce did us a disservice with his “It’s a town full of losers, we’re pulling out of here to win” narrative—that it encouraged us to turn our backs on a hometown and a loving household we were actually lucky to have. But I think that restless urge to escape where you’re from is a natural part of adolescence. Bruce didn’t create that feeling; he just gave it a soundtrack.

***

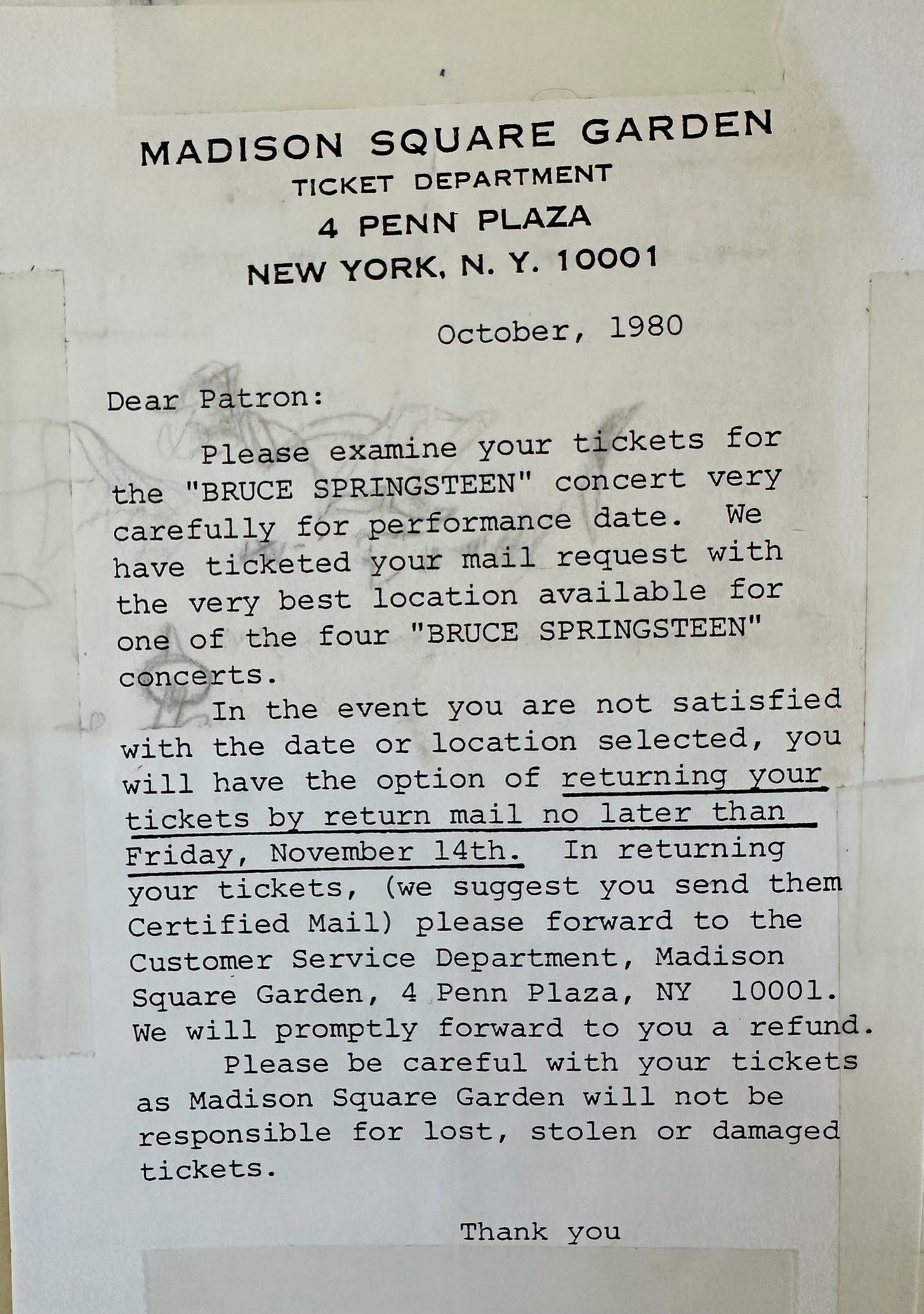

Two years into my obsession, I had listened to a lot of bootlegs, but I had yet to go to an actual Springsteen concert. That changed in my senior year of high school when a friend at the University of Michigan scored two tickets to the opening night of The River tour. I told my parents I wanted to apply to the college and visit the campus for an interview. (Can’t remember if I omitted the concert part.) A few weeks later, I was on a plane to Detroit, then a bus to Ann Arbor, where I somehow located my friend on a campus of 30,000 students without the help of a smartphone.

Seeing Bruce in the flesh was transcendent. There he was! At one point, he asked, “Now who remembers what happens when I do this?” striking a mock rock star pose. I was the first one to scream out, recognizing the comedic bit from a bootleg—and he looked right at me in the third row. I was ecstatic.

After the show, we snuck backstage. Yes, that used to be possible. We waited in our seats as the arena emptied. When an usher tried to shoo us out, I pretended I was feeling nauseous and needed a few minutes. Then we casually slipped under a rope and grabbed beers at the hospitality table to blend in. Members of the E Street Band were everywhere. Saxophonist Clarence Clemons loomed like a mountain in a velour track suit. Decades before his turn as Silvio Dante in The Sopranos, Steve Van Zandt wore a beret and a long gunslinger coat. I went up to each of them and shook their hands. “Mr. Clemons.” “Mr. Van Zandt.” “Mr. Weinberg,” etc. My awkward attempt at showing respect.

When security started checking backstage passes, we ducked into a broom closet and waited. And waited. Until we heard a commotion outside. We peeked out and there he was—Bruce, just a few feet away. Black boots. Black jeans. Leather jacket over a hoodie.

“Hey Bruce, I need a ride back to New York,” I said, wanting him to know I’d traveled hundreds of miles to see him.

“Aw,” he said, “I’m not going that way, man.”

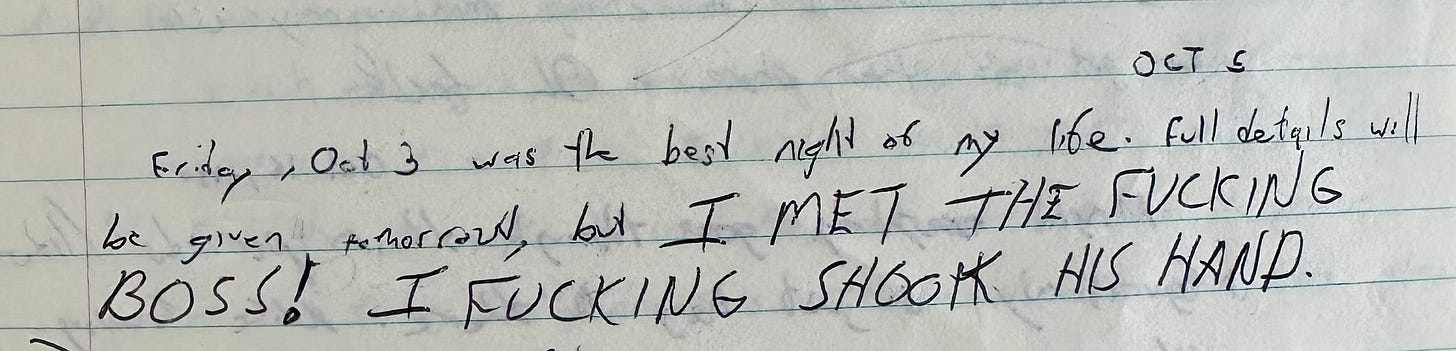

We shook hands. Then we followed him to the venue exit where a rope held back a small group of fans waiting for autographs. But we were standing right beside Bruce on his side of the rope. As if we were in his inner circle. I didn’t even want his autograph, because that would define me as fan, and I felt like I was something more. He was my big brother, after all. A few minutes later, he boarded the tour bus.

My friend and I ran through the streets of Ann Arbor at 1 a.m., stopping strangers to say, “Shake the hand that shook Bruce Springsteen’s!” It was the most magical night of my adolescent life. And the first of 30 or so Springsteen concerts I got to see in all the different phases of his career. In 2007, I even got to meet Bruce again, along with my 12-year-old son, courtesy of my friend

, who produced a Springsteen tribute show at Carnegie Hall. The two of us sat in the empty auditorium as Bruce played “The Promised Land” for the soundcheck, singing with as much conviction as if he were playing for 20,000 people.

***

All of this seems sweet and quaint now. As I type this on my laptop, I can instantly pull up hundreds of live Bruce performances on YouTube. Every holy-grail bootleg I once tracked down and overpaid for is on the Internet Archive. Hell, every time Bruce stops for a hot dog in New Jersey, there’s a video of it on Instagram.

And I wonder: what is it like for young music fans today, with unlimited access to their favorite artists? Part of the allure for me was the elusive hunt for the rare and unheard. Getting Bruce’s work in small, scattered doses made me savor every morsel. If you’re a kid in a candy store with no limits, how long before you’re sick of the candy?

For a long time, that Capitol Theatre cassette was my most treasured possession. It went with me everywhere. But somewhere along the way, we got separated—like Bilbo Baggins and his precious ring. It vanished, along with that era of my all-consuming fandom and so many artifacts and rituals of the analog music world: sleeping out all night for tickets, trading bootlegs, glove boxes full of mixtapes tapes, buying 45s just to hear the rare B-side, and saving ticket stubs as proof that I Was There. It all trails behind me like the tail of a comet—fragments of earlier versions of myself dissolving into nothingness—as I hurtle way too rapidly through time and space.

One of the last times I bought a Bruce record on the actual release day was in 1998, for the first volume of TRACKS. I took my three-year-old son to the now-defunct Tower Records in San Francisco to buy the 4-CD box set. It contained the songs I’d first heard clandestinely on “Fire on the Fingertips” remastered with much higher audio quality. I still have those compact discs in a box somewhere, but my CD player is long gone, another casualty of the streaming music era.

While I’ll always hold a place in my heart for what Bruce and his music gave me (including some lifelong friendships), that desperate need to consume every new song has faded. My world got bigger. And at some point, I realized I’d modeled my teenage self on a fictional character created and played by a very talented artist. So yes, I’ll get around to listening to these “lost albums.” But I won’t be dropping everything tomorrow to do it.

Though every now and then, I’ll stream one of those old Bruce shows and say a quiet hello to the wide-eyed, innocent kid I once was—the one who pressed “record” on a plastic cassette one night and found his first hero.