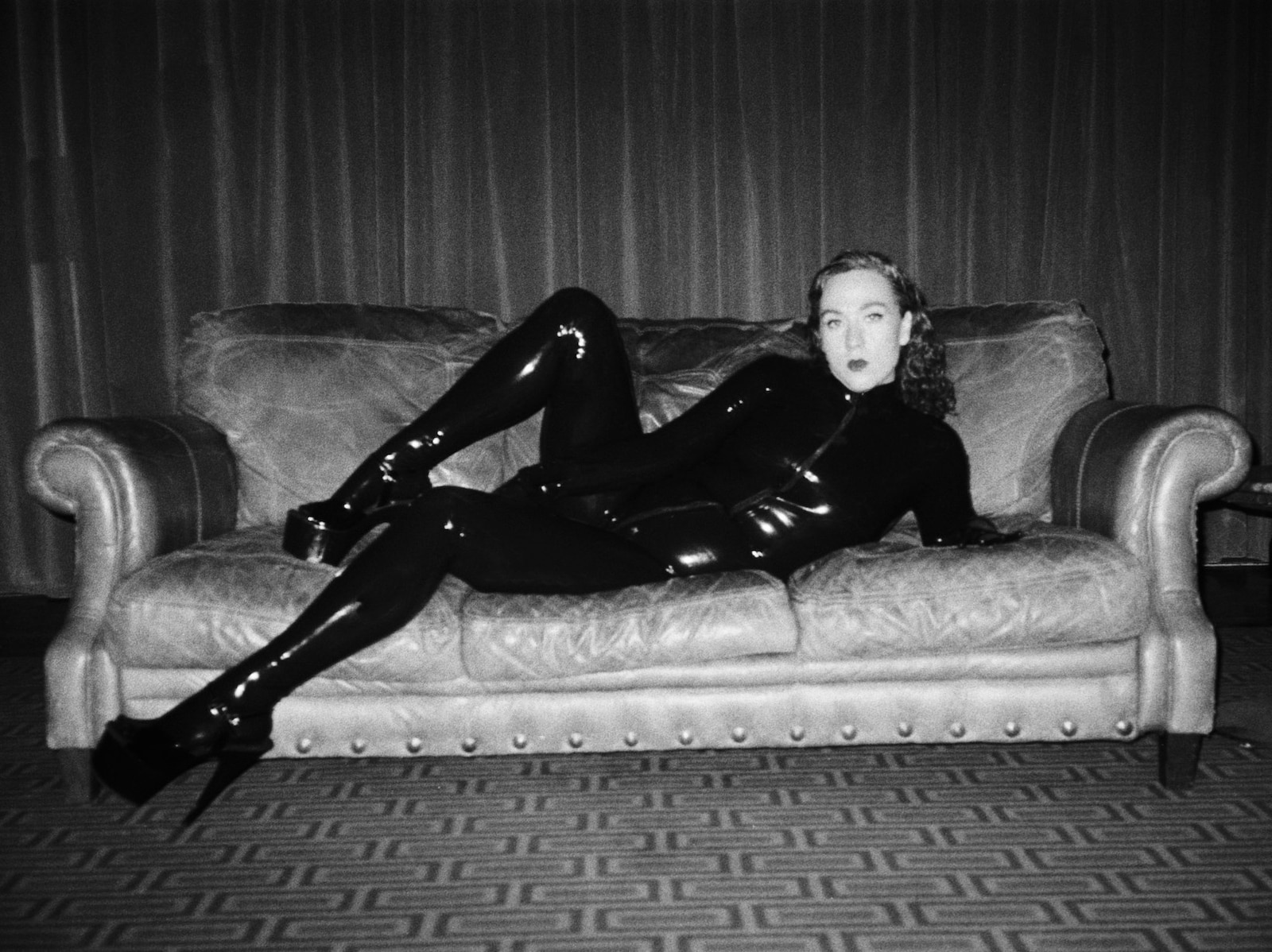

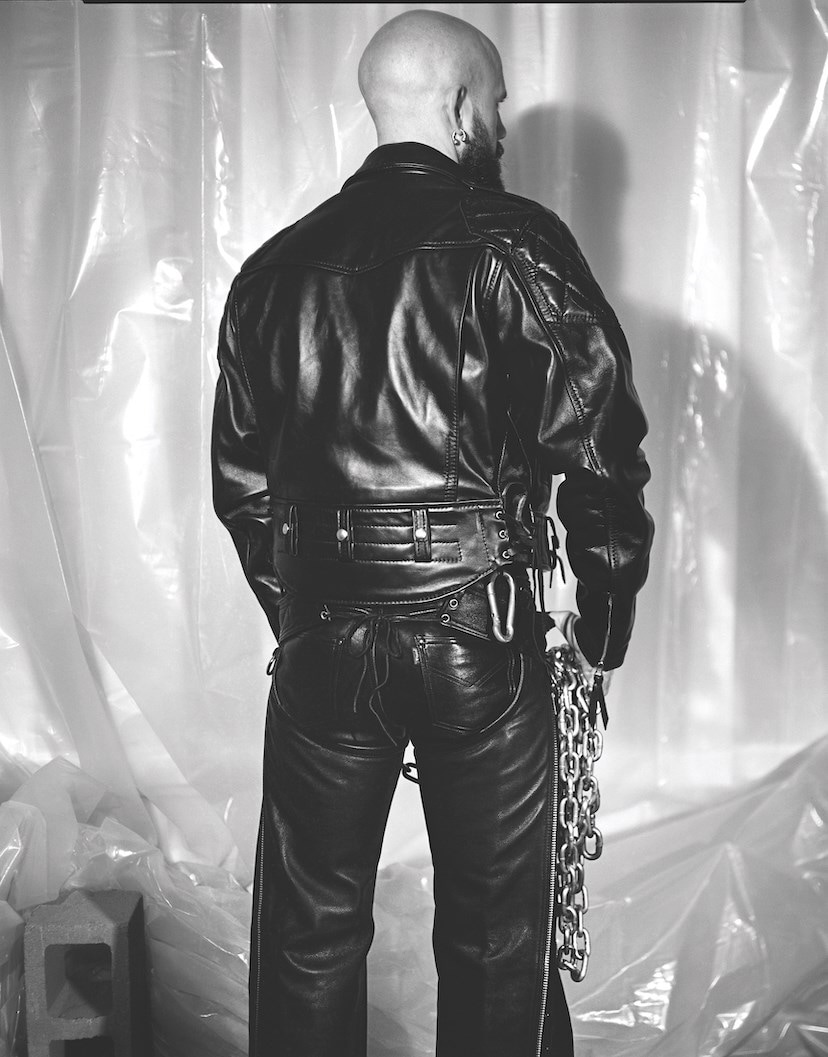

Lead ImageASMRPhotography by Bart Seng Wen Long

is a writer, curator and fetishist. While perhaps somewhat unconventional, this bio line is an important statement both of intent and inspiration behind the journey of the London-based author’s debut book. charts Fedorova’s journey into the worlds of fetish, kink and deviant desire; Alice falling down the rabbit hole, one illicit purchase or experience at a time. But, like Alice, Fedorova ensures to keep her eyes open, contemplating and documenting all she learns, feels and sees through the looking glass.

Writing with keen sensitivity and authentic interest, the writer interviews other fetishists for their thoughts and perspectives; artist Jenkin van Zyl, writer and dominatrix Reba Maybury, designer Harri and mistress, artist and archivist Lady Hinako, and more. Second Skin unpacks the materials – latex, leather – objects (think medical gloves, cars and feet, as well as references to that Prada handbag we all want, the fake Versace trousers she coveted as a child growing up in post-Soviet Russia), as well as the power dynamics that are found within fetish culture. With anecdotes and archival research shaping the narrative, Fedorova explores the meanings and messaging within fetish clubs and the world of dominatrixes and gimps. The approach in the book thinks as much about language – old and new – as the imagery that presents these worlds.

Fedorova traverses the personal and the professional, writing candidly about her journey into fetish, weaving intimate stories of her own sex life into a truly contemporary documentation of what kink means to its communities today. “The more I taught myself how to write openly, politically and directly about sex, the more I realised that I was trying to write myself into existence,” she explains.

Here, the author speaks about the themes and learnings in Second Skin.

Anastasiia Fedorova: Working in fashion was a big part of my personal journey – writing about fashion was my first job at 19, even before I moved to the UK. I was really into semiotics because we had a semantics course in university. I read The Fashion System by Roland Barthes, which talks about the signs and the symbols in fashion and that had a really big impact on me. And then obviously, when you work in fashion, you’re surrounded by brands and beautiful things and all kinds of objects which are beautifully narrated in the fashion world, by designers and writers. I was really interested in how certain things signify beauty or success or a number of other things we chase a lot in our lives. That idea – that you can change, transform yourself depending on what you own and what you wear – was always really important to me.

AF: There are three different things to fetish in my mind: the aesthetics, the embodied experience and sexual culture, and then the politics of it all. I wanted to look at all of that because the fetish aesthetic has existed in fashion for such a long time. A lot of designers and photographers, for example, use it as a tool to talk about the body and sexuality and erotic charge and femininity. Steven Meisel, for example, there’s no question [that] it’s not just a trope he borrows. Robert Mapplethorpe also had such a big influence [on fashion], and his work also came from an authentic place of exploring the sculptures. But then we also do have a short-term approach, when brands basically seek the subversive or the ‘edgy’ to appear novel.

“Empathy is really important. Deep down, we all have desires and thoughts” – Anastasiia Fedorova

AF: I’ve always been interested in using quite simple but evocative language. I wanted [the book] to feel accessible, as if it were an experience. We have sensory and sensual experiences all the time, like, if you jump in cold water … they don’t necessarily have to be sexual. Having an impactful, embodied experience, we all have had it. But do we recognise it, and do we have a desire to write about it? I wanted to write about sex in a similar way to feeling overwhelmed, happy, or having all these different sensations happen.

AF: I feel good about it. I feel like kink and fetish are a bit of a paradox in terms of visibility or exposure these days. Because now, on social media, you have latex influencers (they mostly try on latex). A lot of dominatrixes are working in the educator / influencer space, too. I had a conversation with friends recently; we talked about how fetish and kink actually can become something that brings you a certain amount of social capital these days, which is the absolute opposite of how it used to be. The trade-off is that there’s only certain things you can share … this then changes the meaning of the practice itself. If you only talk about the look, the aesthetic, the most palatable parts of fetish, it takes away from the actual native truth about that.

AF: That’s nice to hear – empathy is really important. Deep down, we all have desires and thoughts, which, especially when it comes to the sexual and the erotic, we are uncomfortable about, or ashamed to share. Whatever sexuality you have, I feel like you always have something you wish you were more free to try, or you wish that you were not so judged about, that you could share with a partner or someone close to you. We all could do with a little bit more empathy towards each other for sharing these things. Think about how close it makes you feel to someone when they share precious, vulnerable things with you. That is, I think, actually a great feeling. If we had more of that, it could create a kinder environment where we could be ourselves more.

Second Skin by Anastasiia Fedorova is published by Granta, and is out now.