BMC Gastroenterology volume 25, Article number: 453 (2025) Cite this article

To examine the progression-free survival from disease worsening after the implementation of routine screening for psychological problems in hospitalized patients with inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) during a long-term follow-up.

The retrospective cohort study enrolled 1265 patients with active IBDs. Their records were stratified into screening cohort (n = 827), receiving screening for psychological problems within 48 h after admission, and a 2:1 propensity score matching was utilized to match cases without screening as controls (n = 438). Primary endpoint was the progression-free survival from disease worsening defined as any IBDs-related emergency room visit, hospitalization or surgery during 12 months post-discharge. Secondary outcomes included quality of life (QoL) using quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) and adverse events.

The rate of progression-free survival from IBDs worsening was observed in 73.2% of patients in screening cohort, while 53.4% of cases in control cohort (odds ratio (OR) = 2.376 (95%CI: 1.864, 3.028), p < 0.001). Compared with controls, cases in screening cohort showed a superior mean of progression-free survival (log-rank p < 0.001) and a greater QALYs during the 12-month follow-up (p < 0.001). Patients in screening cohort were more likely to have hospital-acquired venous thromboembolism and pneumonia due to a longer hospital stay. No severe adverse events were observed.

There was evidence that patients in screening cohort had a better progression-free survival from IBDs worsening than those without these conditions, and also exhibited a better QoL during 12-month follow-up. It should be encouraged that hospitalized IBDs in active phase should be routinely screened for psychological problems that could influence disease course.

Inflammatory bowel diseases (IBDs) including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis is a chronic immune-mediated disorder of the gastrointestinal tract, which is characterized by a fluctuate through periods of inflammation and remission [1]. Age-standardized incidence was reported from 1.47 to 3.01 per 100,000 people in China from 1990 to 2019, and steadily increased with future prevalence likely to be considerably greater than at present by 2050 [2]. Besides the clinical symptoms of abdominal pain, bloody diarrhoea, nutritional failure and weight loss, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis revealed that approximately 25–32% IBD population experienced psychological symptoms such as anxiety and depression, which increased to 39–58% of cases during periods of active disease [3]. These highly co-morbidities further negatively affected patients’ quality of life (QoL) and increased the likelihood of poor outcomes in IBDs including flare, escalation of treatment, hospitalization, emergency department attendance or surgery [4, 5]. Although managing anxiety and depression might improve outcomes in IBDs patients via improving treatment adherence and reducing the need for expensive care, current approaches to psychosocial support showed that clinicians were intervening too late [6]. As to these patients, screening for psychological comorbidities risk and reducing these symptoms should be encouraged based on the results of previous studies [7].

To the best of our knowledge, there were no large sample survey data on the implementation of routine psychological issues screening and its effectiveness about the prognosis of IBDs in China. Therefore, we aimed to investigate whether the psychological distress screening had the ability to identify risk of anxiety and/or depression by gastroenterologists in hospitalized patients with active IBDs using validated disease-specific screening tools, and if necessary, to provide a referral for psychological intervention for the incorporated management. To accomplish this goal, we conducted a case-control retrospective study to collect data on the long-term clinical outcomes including a progression-free survival from IBDs worsening and quality-adjusted life years (QALYs) over 12-month follow-up period after discharge.

The approval was approved by the institutional Ethics Examining Committee of Human Research (TZRMH-KY-20241128) according to the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. The case-control retrospective cohort study was conducted in accordance with the Strengthening the Reporting of Observational Studies in Epidemiology (STROBE) guidelines [8]. All participants signed informed consent after enrollment.

Consecutive patients admitting to the biggest IBD-center in our city for the treatment of IBDs from January 1, 2023 to January 31, 2024 were reviewed from the electronic medical system. Inclusion criteria were as follows: ⑴ diagnosis of IBDs based on a combination of clinical, endoscopic and histopathologic findings based on the American College of Gastroenterology clinical guideline [9]; ⑵ at least a 3-month history of IBDs; ⑶ aged ≥ 18 years old at admission; ⑷ follow-up information available for ≥ 12 months. Exclusion criteria included an unspecified type of IBDs, severe cardiovascular/hepatic/renal dysfunction, infectious disease, malignant tumors, a history of alcohol or drug abuse, pregnancy and/or lactation, length of hospital stay less than 72 h and incomplete medical data.

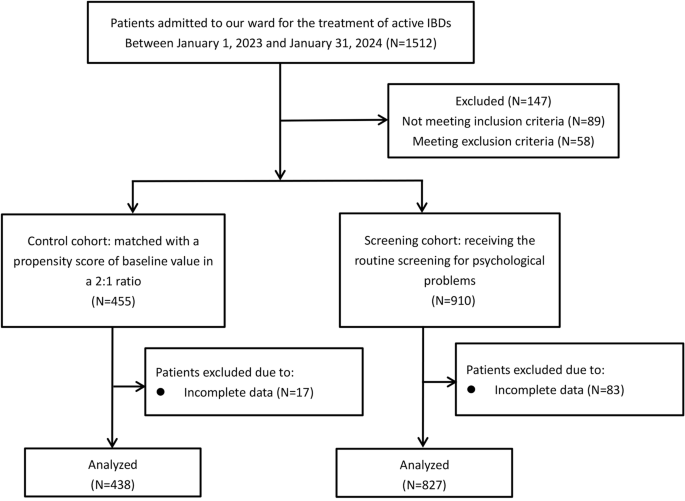

Given that screening for psychological disorders among hospitalized IBDs was not a routine procedure, the patients were engaged to selecting the option most closely aligned with his/her values and preferences after consultation by their doctor. The final cohort consisted of 827 patients receiving the psychological problems screening (screening cohort), whereas 438 cases were classified as controls if they did not receive any screening for psychological problems, and then a propensity score matching by the baseline value via the nearest-neighbor method with a caliper of 0.2: ⑴ age; ⑵ gender; ⑶ race; ⑷ disease type of CD or UC; ⑸ disease duration; ⑹ disease activity by Harvey-Bradshaw Index (HBI) score or partial Mayo (pMayo) score; ⑺ presence of diarrhea, hematochezia, abdominal pain, extraintestinal manifestation; ⑻ history of previous surgery or hospitalization during last 12 months; ⑼ type of medication; and ⑽ comorbidities, in a ratio of 2:1 was performed between exposed and unexposed cases (Fig. 1).

Based on recommendations on psychosocial issues in IBDs from the Association of Crohn’s Disease and ulcerative Colitis Patients (ACCU) and expert review, IBD-patient should be screened for psychological problems, and we encouraged screening for psychological distress within the first 48 h of admission by specially trained nurse staffs.

The 8-item version of the Patient Health Questionnaire (PHQ-8) for the self-reported depressive symptoms was used to identify at-risk groups and assess the severity of depression in clinical settings. It consisted of 8 items with a 4-point Likert-scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day), referring to the symptoms during the previous two weeks. Each item was in accordance with the first 8 symptoms for major depressive disorder of the 4th edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorder (DSM-IV). The total score summed all item scores and rescaled from 0 to 24, with a higher score indicating a higher level of depression, and categorically for major depression if scores > 6 (Supplemental Table 1) [10]. The brief self-administered Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 items (GAD-7) scale was used to screen and assess the severity of anxiety symptoms during the previous two weeks in primary care settings, which composed of 7 items scored using a 4-piont Likert-scale from 0 (not at all) to 3 (nearly every day). Each item corresponds to the symptom criteria of general anxiety disorder of the DSM-IV, by adding the score for which, the total score ranged from 0 to 21. A higher score indicates more severe anxiety and scores > 6 represented positive anxiety (Supplemental Table 2) [11]. Psychological interventions for patients referred to specific psychiatrists after screening in the clinical management of their psychological problems included pharmacological treatment, cognitive behavioral therapy, counseling, and other psychological support. Length of hospital stay was defined as a sum of the consecutive days spent in hospital after admission until discharge occurred. Disease worsening was defined as requires for acute care during 12 months follow-up period after discharge, such as emergency visits, re-hospitalization and surgery associated with IBDs. The health-related quality of life (HR-QoL) was calculated by the quality-adjusted life years (QALYs), which was a composite score of the European quality of life five-dimensional (EQ-5D-5 L) utility values over time using the area under the curve (AUC) method. The EQ-5D-5 L questionnaire contained five domains: mobility, self-care, usual activity, pain or discomfort and anxiety or depression, each of which was rated on a 5-points Likert scale, depending on whether the respondent has no, slight, moderate, severe or extreme problems. Utility scores were calculated by the Euro-QoL crosswalk set of utility index values to their EQ-5D-SL health states [12]. Adverse events were also recorded. The primary endpoint of the study was to estimate the mean of progression-free survival from IBDs worsening that required acute care during 12-month follow-up, defining as IBDs-related emergency visits, readmitted hospitalizations and surgeries.

Data on demographic and other clinical data were retrieved from the electronic medical records (EMRs), while follow-up data were collected through telephone interview by two investigators based on our clinical protocol.

The sample size was calculated using PASS statistical software, version 19.0 (NCSS, LLC. Kaysville, Utah, USA). Based on consensus after a series of expert discussion based on our clinical experience, we supposed the hazard rate for disease worsening when the psychological problems screening was not used for hospitalized IBDs patients was 2. The researchers wanted to show that the psychological problems screening for IBDs clinically better, the hazard rate decreased by at least 50%. We would like to compare sample sizes by a clinical superiority margin of 0.5, when the difference was between − 0.8 and − 0.3 to reach a power of 90% and two-side type I error was 5% with a case/control ratio of 1:2. Taking account of a 20% loss of data, the final sample size was 1512 with 504 cases in control group and 1008 cases in screening group.

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS software version 22.0 (SPSS Inc, Chicago, IL). P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Kolmogorov-Smirnov Z test was performed for normality. Nominal distributed data, non-normally distributed data and categorical data were recorded as mean ± standard deviation (SD), median ± inter quartile range (IQR) and percentage, compared using the Student t test, Mann-Whitney U test and Chi-squared test. The repeated measures mixed-design analysis of variance (ANOVA) was used in-between groups for repeated measurement data, taking the baseline value as covariate. Post-hoc comparison was conducted within group at an adjusted significance level of 0.05/3 = 0.017. The probability of survival from disease worsening was evaluated by the Kaplan-Meier method, with differences among groups assessed by log-rank analysis with 95% confidence interval (CI). The censored point was defined as remission at the last follow-up assessment.

Figure 1 showed the participant flow, attrition and reasons for data loss. From the original patient population of 1512 patients who were hospitalized for the treatment of IBDs, data of 827patients in screening cohort and 438 cases in control cohort were available for final analysis. Due to the 16.3% of loss to data, the reduced sample size still provided sufficient statistical power. Table 1 showed the demographic data and clinical characteristic of patients at baseline; there were no significant differences in the matched variables between two groups.

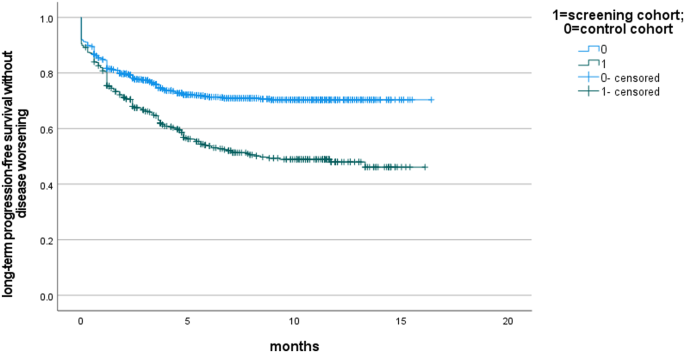

Of cases who screened positive for depression and/or anxiety and accepted referral to a psychiatrist, 25.8% of patients with positive PHQ-9 scores had a confirmed diagnosis of depression, 30.4% of cases with positive GAD-7 scores had a confirmed diagnosis of anxiety, and 21.2% of cases with both positive PHQ-9 scores and positive GAD-7 scores had a confirmed diagnosis of depression and anxiety by psychiatrist. Among these, 14.7% (37/251) received psychological counseling, while 52.5% (132/251), 27.1% (68/251) and 5.6% (14/251) got cognitive behavioral therapy, pharmacological treatment and other psychological support. Compared to controls, cases in screening cohort had a longer length of hospital stay (15.93 ± 2.34 vs. 7.23 ± 1.50, p < 0.001). After performing a subgroup analysis within the screening cohort, patients diagnosed with a psychological disorder also showed a significantly longer length of hospital stay when compared with those without (15.36 ± 6.04 vs. 7.15 ± 1.52, p < 0.001), which might attribute to the argument that the psychological distress contributed to the prolonged hospitalization. Based on Kaplan-Meier curves showed in Figs. 2 and 73.2% of patients in screening cohort, while 53.4% of cases in control cohort was observed without IBDs worsening during a 12-month follow-up period (odds ratio (OR) = 2.376 (95%CI: 1.864, 3.028), p < 0.001). As a matter of fact, the mean of progression-free survival from IBDs worsening was significantly longer in patients receiving psychological issues screening than those as controls (12.03 (95%CI: 11.54, 12.52) vs. 9.01 (95%CI: 8.31, 9.71), log-rank p < 0.001). There was only 1 patient in screening cohort during the 12-month follow-up due to ischemic heart disease, while no death was observed in control cohort. Therefore, we could not evaluate the effectiveness of screening for psychological problems on the mortality rate of IBDs over a 12-month period.

Kaplan-Meier survival curves for patients receiving routine screening for psychological stress for hospitalized IBDs as opposed to the matched control cohort without screening during a 12-month follow-up time. The mean of progression-free survival from IBDs worsening was significantly longer in screening cohort than those in control cohort (log-rank test: p < 0.001)

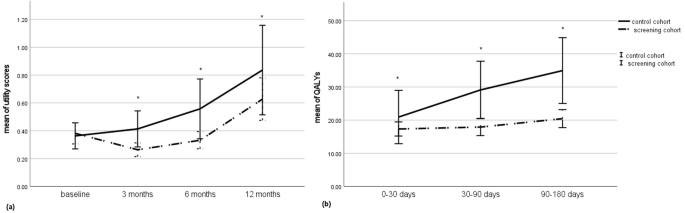

In addition, the mean of EQ–5D-5 L utility scores was significantly lower in screening cohort as opposed to control cohort at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up; and the mean of QALYs calculated by area under the curve in screening cohort was significantly lower than that in control cohort across all time points during the 12 months follow-up (20.94 ± 12.64 vs. 17.33 ± 3.18, p = 0.021 at 3-month; 29.13 ± 13.64 vs. 17.91 ± 3.86, p < 0.001; 34.95 ± 15.59 vs. 20.45 ± 4.05, p = 0.001) (Fig. 3).

Changes in health-related QoL from baseline to 12-month follow-up. (a) the mean of EQ-5D-5 L utility scores was significantly lower in screening cohort as opposed to control cohort without screening at 3-, 6- and 12-month follow-up; and (b) the mean of QALYs calculated by area under the curve in screening cohort was significantly lower than that in control cohort across all time points during the 12 months follow-up. QoL = quality of life; EQ-5D-5 L = European quality of life five-dimension five-level version; QALYs = quality-adjusted life year

No severe complications associated with psychological interventions such as suicidal ideation/behavior, interactions with the criminal justice system, harm to/from others and substance misuse were observed. There were 15.4% of cases experiencing venous thromboembolism in screening cohort, as well as 9.8% in control cohort (p = 0.006). The incidence of difficile infection was also higher in screening cohort as opposed to controls, however, the difference between two cohorts did not reach statistical significance (4.2% vs. 5.1%, p = 0.772).

To our knowledge, this study firstly investigated the effectiveness of routine screening IBDs-patients for psychological distress on the course of IBDs in a large center for the management of IBDs. Our findings demonstrated a significant disparity in psychological problems screening, particular for those with active disease, hospitalized IBDs with routine screening reported a better outcome of progression-free survival without disease worsening during a 12-month follow-up.

The aetiology, severity and progression of such IBDs disorder are thought to be influenced by multiple factors, among which, psychological factors are identified as one of the major contributing factors based on the available evidence [13]. Based on data covering the UK primary care, which included 28,352 with UC and 20,447 with CD, patients with IBDs were more likely to develop anxiety (HR = 1.17 (95%CI: 1.11–1.24)) and depression (HR = 1.36 (95%CI: 1.31, 1.42)) as opposed to controls [14]. According to recent systematic review and meta-analysis, there was evidences for a significant association between symptoms of depression, anxiety and the risk of disease activity flare in IBDs during longitudinal follow-up, with an odds ratio of 1.69 (95%CI: 1.34, 2.13) [15]. In recent years, the brain-gut axis enabling the cross-talk between the nervous system, such as the central nervous system, autonomic nervous system and enteric nervous system, the endocrine system and the immune system was proposed to explain the above-mentioned observations. According to the preliminary study, psychological problems is involved in the permeability, motility, sensitivity and secretion of the intestine system, and then impacts neuroendocrine immune regulation and damages the intestinal immune function and microbiota homeostasis to promote the development and reactivation of intestinal inflammation in animal models [16, 17]. In turn, disordered gut homeostasis in IBD was responsible for driving the brain pathology, exacerbating inflammatory response in the central nerve system, and resulting in anxiety- and depression-like behavior [18]. Besides the gut-brain axis mechanism, chronic psychological problems could also activate inflammatory response through the sympathetic and parasympathetic nervous system, and a certain degree of inflammatory cytokines in the serum of depression and anxiety disorder patients were revealed in a systematic review published amongst 1718 studies [19]. Also, several results suggest that chronic psychological problems lead to activation of Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Stress axis and increased glucocorticoid release failing to modulate inflammatory activity. The form of chronic inflammation will support the pathophysiologic cycle of neurotoxicity, structural neural damage, and diminish the activity and level of brain-derived neurotrophic factors leading to a significant decrease of the therapeutic factors in clinical depression [20]. As a result, identifying the temporal trajectory of psychological disturbances may allow greater insight into understanding the progression of subclinical events as potential ground for disease severity in IBDs. Furthermore, help better interventions in controlling disease to reduce burden of illness and improve quality of life.

As a result, there is a need for psychological distress screening in IBDs care settings. Whereas, the current approach to psychosocial intervention suggests that clinicians are intervening too late during patient care [6]. In order to address these gaps, we addressed mental-health disorders in time during busy clinical appointments and provided available resources for appropriate screening and treatment referrals to psychological doctors. According to our results, chose to 30.4% of cases were identified to be at risk of anxiety and 25.8% of depression in the screening group, which was consistent with previous researches [21], demonstrating that the implementation of routine psychological problems screening for hospitalized IBDs could effectively detect alterations in psychological status and distinguish cases presenting with risk of psychological problems hospitalized IBDs population to overlook patients who need and could benefit from early psychological interventions.

According to our results, patients in screening cohort were more likely to report a longer length of hospital stay, reflecting the fact that depression and/or anxiety disorder could contribute to exacerbating symptoms to prolong the hospital stay in hospitalized IBDs, which was consistent with previous research reporting the OR for hospital length-of-stay in cohort with anxiety and depression disorders amongst 1,718,736 IBDs were 0.05 (95%CI: 0.03, 0.07), p < 0.00122. As a result, the significantly longer hospital stay due to psychiatric comorbidities might also lead to a higher rate of hospital-acquired conditions including venous thromboembolism and difficile infection, which was observed in screening cohort than controls. Furter more, IBDs related psychological disorders were able to reduce medication adherence, which was considered as both an outcome and a risk factor of this vicious circle, and then result in worsening management and prognoses of disease [23]. Consequently, screening and managing psychological comorbidities in IBDs patients during the hospitalization could effectively reduce flare-ups, decrease non-adherence to medications and increase adherence for outpatient follow up, thus potentially improve clinical outcomes [22, 24]. Relaxation, IBD psychoeducation, cognitive restructuring, distraction and social skills were reported as the most utilized interventions for depression and anxiety in IBDs in systematic review, and have shown efficacy in decreasing psychological stress levels and effectively improves inflammatory biomarkers in IBDs [25, 26]. In accordance with the above-mentioned evidences, our findings also proved a wide impact in terms of long-term progression-free survival without IBDs-related emergency visits, readmission and surgeries after integrating screening and referral to treatment for psychological stress.

The previous nomogram model constructed based on the factors influencing the HR-QoL of early patients with IBDs showed that disease activity and psychological distress were the most significant factors affecting the QoL of cases with IBDs, with the highest proportions in the model [27]. On basis of current evidence from systematic review of prospective cohort studies, appropriate intervention for patients identified with psychological factors would reduce IBDs symptom exacerbation, and therefore improve patients’ quality of life [28]. Our results found that patients in screening group revealed a greater HR-QoL during a 12-month follow-up as compared to controls, which provided the evidence that patients with IBDs and anxiety and/or depression might benefit from certain routine screening for psychological issues and referral to effective interventions.

This study has several limitations. First, investigators responsible for outcome assessment failed to keep blind due to the nature of the retrospective study. Second, we did not enroll a healthy control. Third, we did not record the other confounders and infer causality for the described association. In the future, a well-designed, randomized, controlled study with a large sample was needed to verify the findings of the present study.

In conclusion, patients in screening cohort had a better progression-free survival from IBDs-related emergency visits, readmission and surgeries after discharge than those without these conditions, and also exhibited a better QoL during a 12-month follow-up period. It should be encouraged that hospitalized IBDs in active phase should be routinely screened for psychological problems that could influence disease course.

The data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

- IBDs:

-

Inflammatory bowel diseases

- CD:

-

Crohn disease

- UC:

-

Ulcerative colitis

- EMRs:

-

Electronic medical records

- PHQ:

-

Patient Health Questionnaire

- GAD-7:

-

Generalised Anxiety Disorder-7 items

- LOS:

-

Length of hospital stay

- QALYs:

-

Quality-adjusted life years

- AUC:

-

Under the curve

- SD:

-

Standard deviation

- IQR:

-

Inter quartile range

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

The ethics was approved by the Ethics Examining Committee of Human Research of the Affiliated Taizhou People’s Hospital of Nanjing Medical University (approval number: TZRMH-KY-20241128). Written informed consent was obtained from all patients.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Cao, W., Chen, S., Sun, Q. et al. Routine psychological problems screening in hospitalized inflammatory bowel diseases and its effect for progression-free survival from disease worsening. BMC Gastroenterol 25, 453 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12876-025-03889-w