'Ron Delsener Presents' Review: Affectionate Music Promoter Doc

For music-loving New Yorkers who grew up in the pre-digital age, the title of Jake Sumner’s first feature-length film needs no explanation. Beginning in the 1960s, countless newspaper ads announcing the rock and pop concerts that were reshaping showbiz began with three words: “Ron Delsener Presents.”

What Sumner presents is an exuberant look at some of those shows and artists, and a chance to spend quality time with Delsener himself, who turns 89 this year. He officially retired in 2022, but, at least as of the 2023 completion date of the documentary, was still spry, in constant motion, and making deals. Like the impresario Sol Hurok, who was his inspiration — and whom he met, as it turned out, just in the nick of time — Delsener sees no reason to stop doing what he loves.

The Bottom Line A fine mix of biography, pop culture and local history.

Friday, May 30

Patti Smith, Lenny Kaye, Bette Midler, Paul Stanley, Gene Simmons, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, Bruce Springsteen, Steven Van Zandt, Billy Joel, Jon Bon Jovi, Verdine White

Jake Sumner

1 hour 39 minutes

Delsener has done his share of networking and schmoozing, and his business acumen would ultimately have global reverberations. But Ron Delsener Presents is very much a New York story. Born in Astoria, Queens, Delsener now divides his time between Manhattan and East Hampton, and during the months when Sumner was shadowing him, he was still making nightly rounds of the NYC clubs and suburban arenas hosting his shows. For his interviews with musicians, Sumner wisely focuses on people who, like Delsener, grew up in the city or the tristate area, among them Patti Smith, Lenny Kaye, Paul Stanley, Gene Simmons, Paul Simon, Art Garfunkel, Bruce Springsteen, Steven Van Zandt, Billy Joel and Jon Bon Jovi. Bette Midler, who contributes a few fond recollections, isn’t a native of New York but made her name there.

Delsener’s unmatched longevity in the industry stretches “from mom-and-pop to giant global corporations,” music promoter Peter Shapiro, a friend and admirer, points out. A people person who briefly made a living as a door-to-door salesman, Delsener entered the music business with a love of the performers and a knack for cutting deals with municipal leaders as well as managers and agents. He also brought a wild (some would use other words) inventiveness to money-making schemes, notably when he bought up all the detritus from the Beatles’ final hotel stay on their 1964 U.S. tour — the used linens, towels and dinnerware, the ashtrays full of butts — and auctioned them off to rabid fans.

Sponsorship for music events was his idea, too, and whatever the lasting effects of that sea change, the results for a decade beginning in 1966 were an immense gift to New Yorkers. During the summer-long festivals sponsored by a couple of local beer companies, first Rheingold and then Schaefer, an astounding assortment of acts performed at a relatively intimate outdoor venue, Wollman Rink in Central Park. Tickets were $1. As Kiss frontman Stanley puts it, “It was a bargain even then.” Smith, interviewed for the film alongside her longtime collaborator Kaye, calls the festivals “part of what summer was in New York City.”

It wasn’t merely that Delsener backed a staggering who’s who of performers, but that in several notable cases he was presenting their New York debuts: David Bowie’s 1972 show at Carnegie Hall, for one, and the Clash’s 1979 bow at the Palladium, which Delsener had transformed from the run-down Academy of Music into an important showcase for new wave and punk. Speaking of her and Kaye’s band, Smith points to the Palladium as the setting for “probably some of our greatest concerts” (to which I can personally attest, although the extraordinary New Year’s Eve 1976 lineup of the Patti Smith Group, Television and John Cale goes unmentioned here).

Delsener’s skills reached their apex, in many people’s estimation, when he pulled off the 1981 reunion of Simon and Garfunkel for a free Central Park concert. The tiptoeing and patience and maneuvering involved in this coup are relayed with humor thanks to the sharp editing of several interviews. And however cool everyone might be about it from this four-decade remove, footage of the duo’s performance captures their amazed delight as they look out at half a million people on the Great Lawn.

This is also the story of the inevitable meeting (or collision) of Wall Street and rock ’n’ roll. In what Delsener calls a “gambler’s business” because it requires the promoter’s financial investment up front, he ultimately opted to hand that risk to someone with deeper pockets. At the end of a series of mergers and buyouts, consolidation and vertical integration, he maintained his role as promotion maestro, but under the multinational aegis of Live Nation. Delsener has no regrets or apologies. Smith voices a more idealistic perspective when she declares that “rock ’n’ roll should’ve stayed in the hands of the people, and so should’ve the ticket prices.”

The cutthroat aspects of the business are alluded to without delving into gory details. A number of agents and managers (Tom Ross, Al DeMarino, Doc McGhee, Dennis Arfa) weigh in, particularly regarding the clout of powerful agent Frank Barsalona, who divvied up territories for promoters, and who once, in classic mob-godfather fashion, summoned Delsener to a meeting in the Bahamas to give him some news regarding the territorial map that was good for Delsener and not so good for a rival.

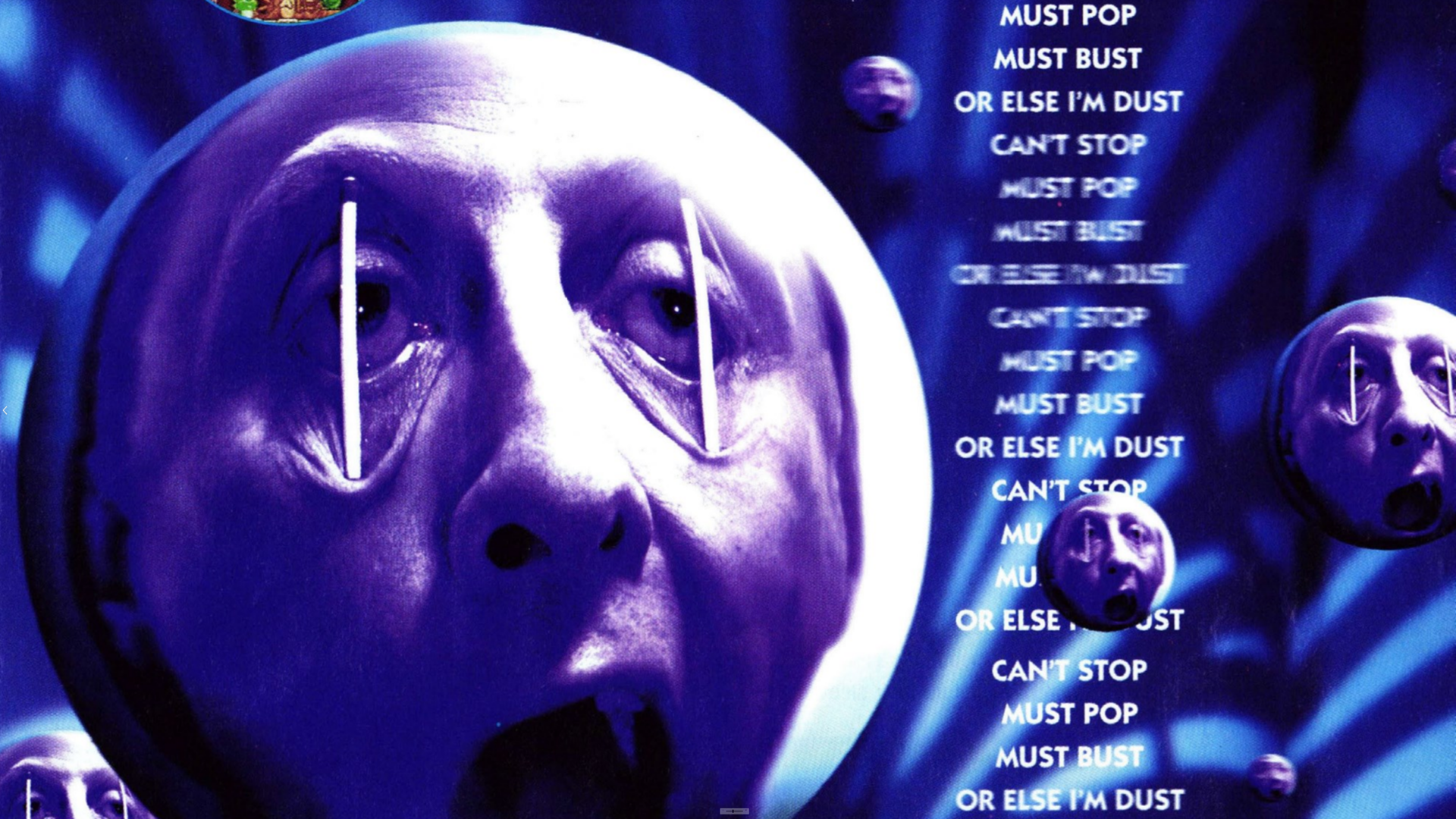

When he isn’t on the fleet heels of Delsener backstage at Madison Square Garden or partying with fans in the parking lot of the Jones Beach Theater, Sumner sits his subject down for a handsomely lighted interview at the Beacon Theatre, or rides shotgun with him while he reminisces from the wheel of his car. In addition to the superb mix of archival material, playful collage-style animation illustrates a few of the recollections. Delsener’s younger sister, Harriet (senior sales director of his business) and his wife and daughter offer illuminating observations. There’s a satisfying balance between biography and pop-culture history.

Those two elements meet most significantly in scenes exploring the memorabilia he’s incessantly collected over the years — newspaper clippings, backstage passes, ticket stubs and assorted tchotchkes — and which now occupies a significant portion of the Delseners’ Long Island house. For nearly anyone facing a lifetime’s worth of souvenirs, there’s an undeniable poignancy. When you’re nearing 90, that’s certainly the case. Whatever his sentimental attachment to all the stuff, he holds the emotions at a humorous, money-focused remove, although the ache is clear when he says, “It’s hard to find somebody to reminisce with.” (There’s an undertow, too — for the viewer, at least — in the moment when Jimmy Buffett, who died in 2023, excitedly tells Delsener backstage that he has an idea about what he wants to do next.)

The most stirring reminiscence, though, belongs to a beaming Jon Bon Jovi, whose anecdote about Delsener goes straight to the beating heart of the person-to-person business that he built, and how, depending on what you value, its success could only lead to its undoing.