OBITUARY: Jibril Aminu, ex-petroleum minister who cracked open oil sector for Nigerian investors | TheCable

Before him, the oil sector was largely dominated by foreign players, with local investors reduced to bit-part roles. Aminu broke the wheel and reinvented a new one that continues to direct the industry to date.

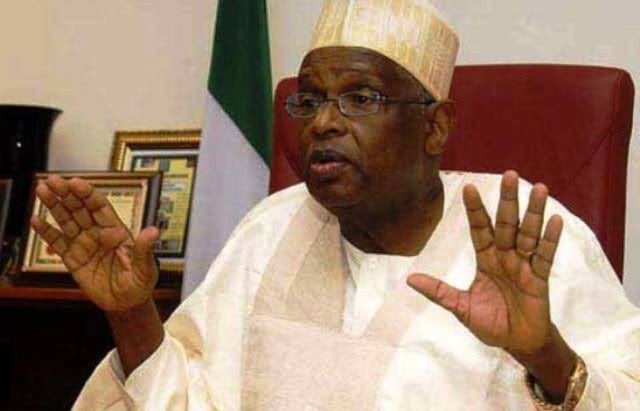

Aminu died on Thursday at 85. The devout Muslim passed on the day of Arafat, one of the holiest in the Islamic calendar.

As his family and loved ones gathered around his remains for Janazah prayer at the national mosque in Abuja, tributes poured in for Aminu amid tears.

President Bola Tinubu said Aminu “epitomised statesmanship and was committed to building a greater Nigeria”. Vice-President Kashim Shetimma called the deceased “the last of the great titans” and “irreplaceable”. Atiku Abubakar, former vice-president, who was present at the final prayer, said Aminu left an “indelible mark on our nation” as a “man of remarkable intellect and dedication”.

Aminu’s best quality was his intellectual versatility. He was a trained cardiologist, an academic of global repute, a two-time minister, a two-term legislator and a revered diplomat. He was brilliant and was never too shy to leave the ivory tower for new challenges. Consequently, he made an impact across every field of endeavour he dabbled in.

As minister for education, Aminu introduced nomadic education for Fulani students and children from other migrant ethnic groups. He was an ex-president of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) during the Gulf War and held his own despite the rift within the organisation. He was a former vice-chancellor of the University of Maiduguri (UNIMAID), where his name and accomplishments remain blazoned in gold.

But there would be no versatile adult called Jibril Aminu without a brilliant boy named Aminu Song.

Aminu was born on August 25, 1939, in Song town in present-day Adamawa state. Like several northern kids born during the colonial era, he adopted the name of his hometown as his surname.

His father died before he was five, and Aminu was raised by his single mother and an uncle who was described “like a big umbrella” to him.

Even at an early age, Aminu’s brilliance was apparent. At his local primary school, he was appointed as rain gauge monitor, and that simple task kindled an interest in science in the young boy’s mind.

“It was the first job I did. Every time it rained, I would run and measure the rain,” he said in a chat with the in 2016.

In 1950, Aminu was admitted to a middle school in Yola before proceeding to Barewa College in Zaria, where he was a classmate with Murtala Mohammed, a former head of state; Aliyu Mohammed, a former chief of army staff; and Mohammed Uwais, a retired supreme court justice.

At Barewa College, Aminu’s retentive brain earned him a very peculiar nickname.

“They said I could not recite the names of students in the register, and I said I could do it,” he recalled.

“They brought a register and I recited it from beginning to end, and they started calling me ‘Roll Call’.”

When Aminu wrote his West African School Certificate Examination (WASSCE) in 1957, he had distinction in six of the subjects he sat for. He was the second northern Nigerian candidate to score distinction (A1) in the English Language WASSCE.

His performance made him eligible for a scholarship to study abroad, but he claimed he missed out due to “politics”.

“They didn’t take me although I was the first to be called for the interview,” Aminu said.

“The Sardauna was the minister of works then. They selected somebody from Bauchi, where the prime minister came from, then Kano and Zaria. I am glad I didn’t go. It was politics. It doesn’t matter whether you are small, big or old, they would still play politics on you.”

Aminu proceeded to the University of Ibadan (UI) to pursue a degree in medicine and dropped Song as his surname. He was decorated with multiple academic awards as an undergraduate. In 1963, he won the Kingsway-sponsored national essay writing competition. He was the top graduating student of the Bachelor of Medicine, Bachelor of Surgery (MBBS) programme during his cohort. He won the Sir Kofo Abayomi Prize and Medal for Community Health.

Following his stellar academic performance, Aminu got a Commonwealth scholarship to study in England. This time, no politics denied him the opportunity.

At the Royal College of Physicians in London, a prized membership typically takes average students four years; Aminu obtained his in a record 12 months. His stay in England was extended to pursue his PhD.

By 1971, Aminu earned his PhD from the University of London. His thesis was titled ” The Mechanisms of Hypertensive Action of Adrenergic Blocking Drugs in Hypertensive Man”.

After four years of holding academic and physician positions at the University of Ibadan and the University of Maiduguri, Aminu was literally called into politics.

As a student of UI, Aminu was one of the founding members of the Northern People’s Club. He said the student group was established because northerners were “isolated and ridiculed” in the campus political discourse.

The club endeared Aminu to a host of northern leaders and associates. The relationships bore fruit after he graduated, and Yakubu Gowon appointed him as the pioneering national secretary of the National Universities Commission (NUC).

“When I drove back to Ibadan, I got a phone call from General Gowon, telling me that I should work for him in the National Universities Commission (NUC),” Aminu said.

“I worked there, and after a few weeks, they announced the names of new universities, including the University of Calabar, University of Jos, University of Sokoto, and University of Maiduguri. Because of political pressure, they added the University of Port-Harcourt and the University of Ilorin. I worked at the NUC till 1979.”

After leaving NUC, Aminu became the vice-chancellor of the University of Maiduguri. He did not hold the position for long before receiving another important phone call, this time relaying a request from Ibrahim Babangida, then the head of state.

“I was in Yola one morning when I got a message from the then inspector-general of police, Gambo, that Babangida wanted me to be the minister of education,” Aminu said.

“Other people also sent messages that day that I was made minister. I feel happy when I see the list of boards we created in the education sector.”

Aminu oversaw the ministry of education from 1985 to 1989. His administration ensured the implementation of the 6-3-3-4 education system, which was operational until it was scrapped in 2025.

He also established the National Commission for Nomadic Education (NCNE) to address the educational needs of students from migrant ethnic groups.

After four years handling the country’s education sector, Aminu was given one of Nigeria’s most critical and consequential jobs: petroleum minister.

Aminu’s versatility was most evident during his tenure as petroleum minister. Previously a medical practitioner and an academic with little knowledge about the oil sector, he caught up with the expertise gap quicker. Early in his tenure, he identified a problem and committed to a solution.

“Long before I came here (to the ministry), I have been interested in Nigerians and oil,” he told the in 1991.

“There is a peculiar estrangement, a feeling that oil is too sophisticated for us to take part in.”

In 1989, Nigus Petroleum was the only indigenous company involved in oil exploration in Nigeria. Others, such as Ado Bayero Oil and Dubril Oil, were dependent on foreign corporations for their operations.

Aminu was frustrated by the “kind of paranoia” that the Nigerian economy suffered through overreliance on foreign actors.

He then began his mission “to make Nigerians understand the oil industry, domesticate it, accept it as something happening in their country, take part in it, learn the technology, learn the managerial aspect and develop the competence to be able to manage it”.

Within two years in office, Aminu allocated about “50 acreages to some Nigerians that we believe can do it”. Moshood Abiola’s Summit Oil and Wale Adenuga’s Consolidated Oil, now known as ConOil, were among the Nigerian entities that benefited from Aminu’s policy.

“We moved into the deep offshore and allocated the blocks there,” Aminu said.

“I decided that we must train our people to be able to produce their own oil. We told them that if one of them could produce petroleum and export it, our point would have been made, that Nigerians could produce petroleum and export it.”

According to , as of February 2025, indigenous oil firms are now responsible for 60 percent of Nigeria’s crude output.

Aminu also spearheaded the formation of the African Petroleum Producers Association (APPA) and served as its president in 1991. He was also elected the president of the Organisation of Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) from 1992 to 1993.

Aminu was Nigeria’s ambassador to the US from 1999 to 2003. Upon his return from diplomatic duties, he entered into active politics for eight years, representing Adamawa central in the senate.

According to Murtala, Aminu’s son, the electorate voted for him because of his erudition and virtue as a human being.

“Some called him ’Professor dukaduniya’ (professor worldwide in Hausa). If you heard him speak, you may likely have voted for him. He was a very convincing and valuable politician,” Murtala told in 2018.

In 2010, Aminu was conferred the chieftaincy title of “Bobaselu of The Source” by Oba Sijuade, the immediate past Ooni of Ile-Ife.

Aminu was survived by nine children and Ladi Ahmed, his wife.