When NSW Treasurer Daniel Mookhey came to office in 2023, his priorities were clear: clean up the mess, rein in debt and wrangle the state’s finances into shape.

The state’s books, laid bare on Tuesday, show that focus hasn’t changed. Mookhey has managed to pull a budget surplus back into view within the next three years, from what was previously a run of four deficits.

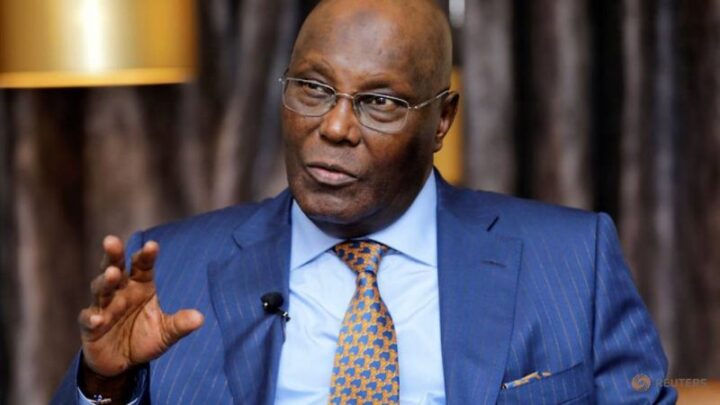

Treasurer of NSW Daniel Mookhey speaks about the budget on Tuesday.Credit: Dominic Lorrimer

There’s a $5.7 billion deficit this financial year, which is bigger than expected six months ago. But the red ink will apparently turn black by 2027-28: a $1.1 billion surplus followed by another $1 billion surplus the following year.

Mookhey insists those surpluses are thanks to his commitment to keeping the government’s belt tight.

Despite a $1.2 billion cash splash to boost child protection, failed attempts at reining in workers’ compensation costs (expected to worsen the budget by $2.6 billion in coming years) and an interest bill $280 million higher over the four years to 2027-28 than expected six months ago, Mookhey is expecting to cap annual spending growth at about 2.4 per cent over the next five years.

Loading

But the treasurer has also been hit with some good luck – including the state’s property prices, which continue to surge. While the number of property transactions has been weak amid high interest rates, the government expects further rate cuts to boost buyers’ confidence, helping to bring in more than $13 billion in revenue from transfer duties such as stamp duty this coming financial year.

The state’s overall revenue will hit a record $124 billion in 2025-26 – nearly $1 billion more than forecast six months ago. And over the next four years the state government expects to rake in $11 billion more than it forecast back in December. That’s also thanks to a higher GST carve-up for the state than expected, and stronger federal government funding for areas such as schools and transport infrastructure.

The state’s net debt will climb from $109 billion to nearly $134 billion by June 2029 – more than four times the amount spent every year on the state’s health system. As a share of the state’s economy, however, the government’s net debt will climb from 12.8 per cent this year to nearly 14 per cent in 2027, before tapering back to 13.1 per cent by June 2029.

While the state’s finances are broadly in shape, the outlook for the state’s economy is weaker than previously expected. Real gross state product – a measure of NSW’s economic growth – has been revised down to 1.75 per cent in the coming financial year, from the 2.5 per cent expected six months ago.

Mookhey blames this partly on geopolitical uncertainty, but that’s far from the full story.

The direct impact of the tariffs announced by US President Donald Trump are expected to be modest since the state’s exports to the US only make up 0.6 per cent of the NSW economy. “If tariffs result in reduced demand from the US, NSW exporters will likely find alternative markets for selling their products,” the budget explains.

The indirect effects are slightly more significant, with delayed business investment and consumer spending expected to slice half a per cent from the state’s economic growth over two years.

However, Mookhey expects a pick-up in consumer spending to lead a gradual recovery. He is banking on people spending more as income tax cuts and lower interest rates come into play, helping to shift growth from the public sector – which has dominated growth in the post-pandemic period – to the private sector.

The shift from public to private heavy lifting is also reflected in the government’s approach to housing. After throwing money into social housing, Mookhey’s big housing policy this year is about fast-tracking up to 15,000 extra homes over the next five years.

Developers typically must sell 25 per cent of off-the-plan homes before locking in a loan. Using the state’s balance sheet, the government will guarantee up to $1 billion worth of projects at a time to help developers secure loans more quickly and start building earlier.

Mookhey is also taking his foot off the pedal on shiny major infrastructure projects, focusing instead on laying out the tracks for housing by replacing the pipes and poles needed to make energy and water flow to homes. The government’s overall infrastructure investment is angling lower over the next few years, meaning the pressure on the state’s limited construction resources will probably come off.

There is, however, a lack of ambition. Federal Treasurer Jim Chalmers earlier this month put productivity squarely on the national agenda, opening the door to tax changes aimed at boosting the country’s living standards.

Mookhey’s budget makes no attempt at taking on tax reform. Perhaps the clearest opportunity – moving from stamp duty to a broad-based land tax – was scrapped by the Minns government when it came to power. There’s no sign of that – or any other tax – changing.

While curbing government spending growth is a smart move – especially after ratings agency S&P Global earlier this year put states on notice for their ballooning balance sheets – Mookhey must also take on productivity-boosting tax reform.

Without this the NSW economy is on track for continued lacklustre growth, and real wages will struggle to grow. Perhaps most importantly for Mookhey, it risks plunging the budget back into a position he has tried so hard to get it out of.