Archives of Public Health volume 83, Article number: 171 (2025) Cite this article

Longitudinal reciprocity between gastrointestinal disease (GID) and depression has not been explored among middle-aged and older adults.

This study included 12,366 participants aged 45 and above from the 2015, 2018 and 2020 survey waves of the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS) conducted in China. Depression was defined as a score of 10 or higher on the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10). The GID was identified on the basis of the presence of physician-diagnosed stomach or other digestive diseases, excluding tumors or cancers. Cox proportional hazards models were used to explore the longitudinal relationship between baseline GID and subsequent depression onset, as well as the association between baseline depression and newly reported GID. To assess bidirectional associations and the strength of different directional associations simultaneously, cross-lagged panel models (CLPMs) were also employed. Stratification analyses were performed to identify vulnerable populations for each directional path.

The baseline prevalence rates of GID and depression were 24.6% and 32.8%, respectively. Cox models revealed significant associations between baseline GID and new-onset depression (HR = 1.36, 95% CI: 1.25, 1.48) and between baseline depression and newly reported GID (HR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.41, 1.84). After controlling for both confounders and interwave correlations, the CLPM demonstrated longitudinal bidirectional associations between GID and depression across three survey waves (P value < 0.001 for all cross-lagged coefficients) and revealed that gastrointestinal health was the stronger driving force in its dynamic interaction with depression. Females and urban residents are more susceptible to the impact of GID on depression onset, with females also being more vulnerable to depression influencing GID onset.

GID may stem from worsening depression, whereas GID itself contributes to the aggravation of depression among middle-aged and older adults, suggesting that targeted interventions for either gastrointestinal health or depression may yield reciprocal benefits over time.

Text box 1. Contributions to the literature |

|---|

• Provides longitudinal evidence suggesting bidirectional associations between gastrointestinal diseases and depression in Chinese elderly, addressing critical knowledge gaps in aging populations. |

• Application of cross-lagged modeling reveals gastrointestinal health as the stronger driver in this dynamic interplay, advancing methodological approaches for comorbidity studies. |

• Identification of vulnerable subgroups (females and urban residents) enables prioritized resource allocation for socioeconomic-status-sensitive health interventions. |

Gastrointestinal diseases, encompassing gastritis, irritable bowel syndrome(IBS), functional dyspepsia(FD), peptic ulcer disease (PUD), gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), pose a significant health burden worldwide [1]adversely affecting quality of life and imposing considerable economic strain on the healthcare system. In 2019, there were estimated to be 2.86 billion cases of digestive system diseases, leading to 8 million deaths and 277 million disability-adjusted life years (DALYs) lost [2]. This can be attributed to a variety of factors, such as physiological changes related to aging, lifestyle factors, dietary patterns, and the cumulative effect of long-term exposure to environmental and genetic risk factors [2]. The impact of gastrointestinal diseases on elderly individuals is multifaceted. From the perspective of public health, GID has a significant effect on the utilization of medical care, including frequent hospitalization, outpatient services and long-term medication [3]. In addition, the social impact should not be underestimated. GID leads to social isolation, reduced work efficiency and increased dependence on nursing staff, all of which increase the psychological burden on patients [3].

Depression is recognized as a major mental health disorder that is strongly related to increased disability rates and mortality, especially among elderly individuals. Globally, depression affects more than 300 million people, with the highest prevalence in the 55–74 age group, where the prevalence is 7.5% for women and 5.5% for men [4]. In China, owing to rapid population aging, the elderly population is estimated to reach 440 million by 2050 [5]. This demographic change has significant public health implications, particularly in exacerbating the growing burden of depression among the elderly [4]. Previous studies have reported that the increasing incidence of depression among middle-aged and older adults in China is posing an immediate threat to the national health system [6].

Depression is related not only to psychological distress but also to physiological changes that may affect gastrointestinal function. Several studies have demonstrated a higher prevalence of gastrointestinal symptoms and disorders, including irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) [7]peptic ulcer (PUD) [8] and functional dyspepsia (FD) [9]among individuals with depression. Conversely, individuals with chronic gastrointestinal diseases frequently experience depression [10]highlighting the potential interplay between mental health and gut health through shared physiological and behavioral mechanisms. Emerging evidence suggests the gut-brain axis serves as a key mediator of bidirectional communication between the gastrointestinal tract and central nervous system [11]. This neuroendocrine-immune network enables top-down effects where psychological distress alters gut motility, permeability and microbiota composition through hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis activation and vagal nerve modulation [12]. Conversely, bottom-up pathways allow gut-derived inflammatory cytokines, microbial metabolites, and afferent vagal signals to influence neuroinflammation and neurotransmitter synthesis [12]. Such bidirectional crosstalk provides a plausible biological foundation for the observed comorbidity. Building upon these observations, we hypothesize that depression and gastrointestinal diseases are not only common comorbidities but also risk factors for each other. If this bidirectional association holds, it implies that interventions targeting one condition could confer protective effects on the other, offering a promising approach for integrated prevention and treatment. However, while several cross-sectional studies have reported associations between GID and depression, the temporal precedence and directional nature of this relationship remain unexamined, particularly within China’s rapidly aging population where the interplay between physical and mental health may be exacerbated by demographic shifts.

In this study, we utilized data from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), a nationally representative cohort, to investigate the longitudinal bidirectional association between the GID and depression in middle-aged and older Chinese adults. Stratification analyses were also conducted to determine the vulnerable subgroup for each potential directional relationship, providing insights into population-specific and modifiable risk factors.

This study was based on data from participants in CHARLS, a nationally representative aging cohort in China (https://charls.pku.edu.cn/en/) [13]. Briefly, the CHARLS is a population-based, ongoing longitudinal cohort study targeting Chinese adults aged 45 years and older. The CHARLS included participants from 450 rural villages and urban communities across 150 counties/districts in 28 provinces. In CHARLS, Participants were followed every two or three years, with a small cohort of new participants added in each survey wave. To date, CHARLS has data covering five waves. The CHARLS obtained ethical approval from the Biomedical Ethics Review Committee of Peking University (IRB00001052–11015), and all participants provided informed written consent.

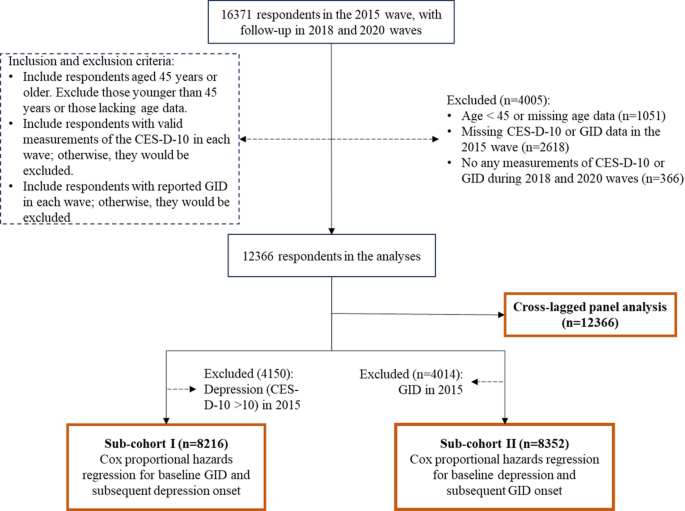

This study used the latest three waves of CHARLS data (i.e., the 2015, 2018, and 2020 waves), which ensured a relatively stable cohort population for longitudinal analysis and reduced the influence of unmeasured time-varying confounders. Initially, this study included 16,371 participants who were in the 2015 survey wave and were followed up across the 2018 and 2020 survey waves. Then, we excluded 1005 participants who were younger than 45 years or had missing age data, 2618 participants who lacked measurements of the CES-D-10 score and GID at baseline, and 366 participants who had no CES-D-10 or GID measurements during the follow-up period. Ultimately, 12,366 participants were included in the final analyses. Figure 1 provides an overview of the participant selection process.

The inclusion and exclusion criteria and workflow of this study. Abbreviations: GID, gastrointestinal disease; CES-D-10, scores on the 10-item Centre for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale

In CHARLS, respondents were asked to complete the 10-item Center for Epidemiological Studies Depression Scale (CES-D-10) at each survey wave. The CES-D-10 consists of ten questions, with each one specifically targeting different negative moods. Participants rated each question according to the frequency within the preceding week: 0 for less than one day, 1 for 1–2 days, 2 for 3–4 days, and 3 for 5–7 days. Thus, the total score of the CES-D-10 ranges from 0 to 30, and a higher score indicates more severe depression. The CES-D-10 has been widely recognized for its ability to identify individuals with depression [14]. Additionally, previous studies have demonstrated that the CES-D-10 has high sensitivity in elderly Chinese adults [15].

On the basis of prior research, a cutoff score of 10 has been identified as optimal for detecting participants’ depression status in the CHARLS [16]. Hence, we defined depression as a CES-D-10 score ≥ 10 and non-depression as < 10. For all analyses, we used this binary classification (depression vs. non-depression) for modeling.

The determination of the GID was based on responses to the health status and functioning questionnaire administered during the 2015 and 2018 survey waves. The participants were asked questions such as “Have you been diagnosed with a gastrointestinal disease (The CHARLS questionnaire specified digestive diseases as chronic conditions requiring medical management, including but not limited to gastritis, gastric/duodenal ulcers, inflammatory bowel disease, liver cirrhosis, and functional gastrointestinal disorders excluding tumors or cancer) by a doctor?” Respondents who answered “Yes” were classified as having gastrointestinal diseases. The surveys were conducted by trained interviewers via standardized questionnaires harmonizing with international aging studies. This self-report method with standardized questionnaires serves as an effective tool for evaluating the prevalence of chronic diseases, including GID, among middle-aged and older people and has been widely used in large-scale epidemiological studies [17]. We used this binary classification of GID status (yes vs. no) for analyses in this study.

Potential covariates considered in the analysis included age (in years), sex (male, or female), education level (illiterate, less than high school, or high school and above), residence (rural, or urban), marital status (married, or other categories such as partnered, separated, divorced, widowed, or never married), body mass index (BMI, kg/m²), alcohol consumption (never, occasional [fewer than three times per week], or regular [more than three times per week]), smoking history (never, or ever), participation in social activities (yes, or no), household cooking fuel (classified as clean, including gas, liquefied petroleum gas, biogas, electricity, or solar energy, or solid, including wood, coal, or crop residues), personal earnings after tax (positive, or nonpositive), and self-reported physician diagnoses of hypertension, diabetes, and dyslipidemia. Apart from age and BMI as continuous variables, other covariates were modeled as categorical variables in our analyses.

Baseline demographic characteristics were summarized for participants, stratified by GID status (yes or no) and depression status (yes or no). Continuous variables are reported as the means with standard deviations (SDs) and were compared across groups via the parametric t test. Categorical variables are presented as counts and percentages, with group comparisons conducted via the chi-square test.

As shown in Fig. 1, two distinct subcohorts were established for directional analysis. In the subcohort for the GID→depression analysis, we excluded 4,150 participants with baseline depression (CES-D-10 ≥ 10) in the 2015 wave, resulting in 8,216 depression-free individuals. Cox proportional hazards (PH) regression models were used to assess the association between baseline GID status and incident depression during follow-up. In the subcohort for the depression→GID analysis, we excluded 4,014 participants with baseline GID in the 2015 wave, retaining 8,352 GID-free individuals. Cox PH regression models were used to evaluate the effect of baseline depression status on subsequent GID diagnosis. Hazard ratios (HRs) were estimated from five models with various adjustments for potential confounders: Model 1 was the unadjusted model; Model 2 included adjustments for demographic factors, including age, sex, BMI, residence, education level, and marital status; Model 3 was adjusted as Model 2 with further adjustments for lifestyle factors, including alcohol consumption, smoking status, and engagement in social activities; Model 4 was adjusted as Model 3 with further adjustments for proxies of income levels, including household cooking fuel and personal earnings after tax; Model 5 (fully adjusted model) was adjusted as Model 4 with further adjustments for hypertension and diabetes. Missing covariate data were addressed via multiple imputation by chained equations (MICEs).

The Cox PH models used the follow-up year as the time scale, with the date of the 2015 wave as the original time. Follow-up years were calculated from the date 2015 wave to the date of GID events (when participants reported GID) or censoring events including loss to follow-up (when participants couldn’t be reached for subsequent waves), death (if it occurred during the follow-up period), and the end of the last available wave in 2020. It should be noted that due to the nature of our longitudinal survey with wave-based follow-up, the event times are interval-censored. Hence, the HRs obtained from the Cox PH models are approximations, which should be interpreted with caution.

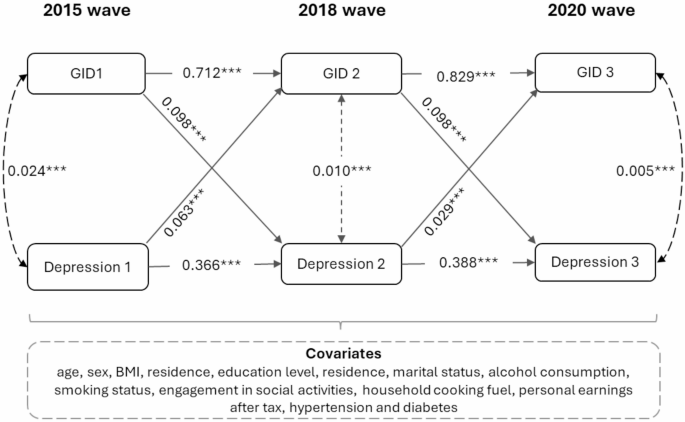

To investigate the longitudinal bidirectional relationship between GID and depression simultaneously, we further constructed a cross-lagged panel model for all 12,366 study subjects (Fig. 1). CLPM allowed us to examine the reciprocal relationship between GID and depression over time while accounting for their temporal intercorrelations as well as potential confounders [18, 19]. Moreover, the CLPM can also compare the strengths of different directional associations via standardized weighted coefficients, thereby identifying the predominant drivers of the bidirectional dynamic interplay. We constructed a fully adjusted CLPM, accounting for age, sex, BMI, education level, residence, marital status, alcohol consumption, smoking status, engagement in social activities, household cooking fuel, personal earnings after tax, hypertension and diabetes. Full information maximum likelihood (FIML) estimation was used to handle missing covariate data in the CLPM. FIML is a single-step maximum likelihood approach for missing data that has been widely used in structural equation modeling, like CLPM [20, 21]. CLPM estimated the standard coefficients that represent the strength and direction of relationships between variables over time, both within a variable (autoregressive effects) and between different variables (cross-lagged effects); specifically, they indicate how much a change in one variable at one time point predicts a change in another variable (or the same variable) at a later time point, while controlling for interwave correlations (i.e., correlation between two study variables at the same time point) and confounders in the model.

Given the estimated standardized coefficients of the bidirectional relationship between depression and GID from CLPM, we used a two-sample z-test to compare the strength of different directional associations. Here, the formula of z-test is \(\:({\beta\:}_{1}-{\beta\:}_{2})\pm\:1.96\sqrt{{se}_{1}^{2}+{se}_{2}^{2}}\), where \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\) represent the standardized coefficients for different cross-lag paths from the CLPM, and \(\:{se}_{1}^{2}\) and \(\:{se}_{2}^{2}\) are standard errors (s.e.) of \(\:{\beta\:}_{1}\) and \(\:{\beta\:}_{2}\), respectively.

Several sensitivity analyses were conducted in this study. First, in each longitudinal unidirectional analysis, we performed stratification analyses by age, sex, BMI category, education level, marital status, residence, alcohol consumption, and smoking history to determine vulnerable subgroups, all of which were based on the fully adjusted Cox PH model (Model 5). A two-sample z-test was conducted to assess whether there were significant differences in the estimated effects across different stratifications [22, 23]; here, the formula of z-test is \(\:({Q}_{1}-{Q}_{2})\pm\:1.96\sqrt{{se}_{1}^{2}+{se}_{2}^{2}}\), where \(\:{Q}_{1}\) and \(\:{Q}_{2}\) represent the regression coefficients for the respective stratification, and \(\:{se}_{1}^{2}\) and \(\:{se}_{2}^{2}\) are their standard errors. Second, in the lagged cross-panel model, we repeated the analysis via MICE to address missing covariate data. Additionally, both the longitudinal unidirectional analyses and cross-lagged panel analyses were repeated among 10,568 participants with complete CES-D-10 and GID measurements across all survey waves to mitigate potential bias from unmeasured outcomes.

All the statistical analyses were conducted via R software (version 4.3.1), and a two-tailed P value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

There were 12,366 participants included in this study, with a mean (SD) baseline age of 60.5 ± 8.7 years; among them, 5779 (46.7%) were male, 1469 (11.9%) had an education level of high school and above, and 4363 (35.3%) were urban residents. As summarized in Table 1, at baseline, 4014 (32.5%) participants had GID, and 4150 (33.6%) participants had depression. Compared with those without a GID, participants with a baseline GID were more likely to be female, illiterate, unmarried, and reside in rural areas (all P values < 0.05); participants with a GID also tended to have a lower BMI, a history of smoking, no engagement in social activities, lower personal earnings, reliance on solid cooking fuels, and a higher prevalence of diabetes (all P values < 0.05). The baseline prevalence of depression was significantly greater among females, individuals with low education levels, rural residents, those who were unmarried, those with a lower BMI, and those without a history of alcohol consumption or smoking (all P values < 0.05); depression was also more common among individuals who did not engage in social activities, had nonpositive personal earnings after taxes, relied on solid household cooking fuels, or had a history of hypertension and diabetes (all P values < 0.05).

As shown in Table 2, all five Cox PH models consistently demonstrated an increased risk of new-onset depression associated with the baseline GID. According to the fully adjusted Model 5, participants with GID had a 36% higher risk of developing depression (HR = 1.365, 95% CI: 1.25–1.48, P value < 0.001).

All five Cox PH models consistently suggested that baseline depression was associated with an increased risk of newly reported GID. According to the fully adjusted Model 5, baseline depression conferred 61% increased risk of incident GID (HR = 1.61, 95% CI: 1.41–1.84, P value < 0.001).

Figure 2 shows the standardized coefficients of the three-wave CLPM after controlling for interwave correlations and potential confounders. Baseline GID status in 2015 was significantly associated with subsequent depression onset in the 2018 wave (β = 0.098, P value < 0.001), and GID status in 2018 remained significantly associated with depression risk in the 2020 wave (β = 0.098, P value < 0.001). Similarly, there was a significant association between depression in 2015 and newly reported GID in the 2018 wave (β = 0.063, P value < 0.001) and between depression in 2018 and newly reported GID in the 2020 wave (β = 0.029, P value < 0.001). Moreover, both depression and GID status were significantly temporally correlated across adjacent survey waves, which were adjusted in the CLPM. A comparison of the standardized coefficients by z-test revealed that the baseline GID had a more pronounced effect on subsequent depression onset that of baseline depression on later GID onset, with standardized coefficients (s.e.) of 0.098 (0.007) vs. 0.063 (0.007) (P for z-test < 0.001) from 2015 to 2018 waves and standardized coefficients (s.e.) of 0.098 (0.007) vs. 0.029 (0.006) (P for z-test < 0.001) from 2018 to 2020 waves.

Cross-lagged analysis for gastrointestinal disease (GID) and depression among middle-aged and elderly adults (aged ≥ 45 years) from the China Health and Retirement Longitudinal Study (CHARLS), 2015–2010. Standardized coefficients were reported. Single-headed arrows represented regression paths. Double-headed arrows represented cross-sectional correlations. Symbol * indicates 0.01 ≤ P < 0.05; Symbol ** indicates 0.001 ≤ P < 0.01; Symbol *** indicates P < 0.001

The results of stratification analysis for different unidirectional associations are shown in Table 3. In the stratification analysis for the unidirectional association of the baseline GID and subsequent depression onset, the estimated effects were stronger in females (HR = 1.46) than males (HR = 1.24) (P for effect modification = 0.011), and stronger in urban residents (HR = 1.51) than rural residents (HR = 1.30) (P for effect modification = 0.036); a modification effect by education was also observed when comparing the HRs between illiterate education (HR = 1.41) and high school and above education(HR = 1.88) (P for effect modification = 0.018). In the stratification for a unidirectional relationship between baseline depression and newly reported GID, the estimated effects were more pronounced among females (HR = 1.74) than males (HR = 1.42) (P for effect modification = 0.028), and were stronger in those with a high school and above education (HR = 2.21) compared those without formal education (HR = 1.43) (P for effect modification = 0.007).

When the CLPM with MICE was constructed to handle missing covariate data, the estimated standardized coefficients were strongly consistent with the primary findings (Figure S1). Moreover, when analyses among participants without missing values for the CES-D-10 and GID across the three survey waves were restricted, the results from the longitudinal unidirectional and cross-lagged panel analyses remained consistent, further confirming the robustness of the results (Table S1 and Figure S2).

This study provides longitudinal evidence suggesting bidirectional associations between gastrointestinal diseases (GID) and depression among middle-aged and older Chinese adults, aligning with previous unidirectional research while corroborating the yet-to-be-fully explored reciprocal relationships. Both the unidirectional Cox PH model and the bidirectional CLPM consistently revealed a significant association between baseline GID and an elevated risk of subsequent depression onset, thereby substantiating the hypothesis that GID serves as a risk factor for the development of depression. Conversely, when examining the impact of depression on gastrointestinal health, our unidirectional Cox PH model and bidirectional CLPM analyses consistently demonstrated that baseline depression significantly increased the newly reported GID. Therefore, our findings revealed a longitudinal bidirectional relationship between GID and depression among middle-aged and older adults. Additionally, the standardized cross-lagged path coefficients revealed that although the bidirectional associations were statistically significant, GID status served as a stronger driving force than depression in their dynamic interplay.

The results of this study not only align with previous unidirectional research but also corroborate the yet-to-be-fully explored bidirectional relationships. On the one hand, consistent with our use of the GID as an outcome pathway, prior studies have demonstrated a unidirectional positive correlation between episodic or chronic depression and various GID indicators [24]. On the other hand, while not comprehensively investigated, published longitudinal survey findings lend support to the perspective of the GID as a risk factor for depression. For example, a previous study used a two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) design to evaluate the potential causal relationship between depression and four gastrointestinal diseases; the results revealed that depression predicted by genetics may increase the risk of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), IBS, PUD and nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) [25]. Moreover, through reverse MR, genetically predicted GERD or IBS may increase the risk of depression. Ruan et al. systematically explored the association with depression in a wider range of patients with GID and reported that genetic susceptibility to depression was associated with an increased risk of 12 gastrointestinal diseases [26]. These previous results jointly support the view that depression may be risk factors for the development of GID and that symptoms of GID may also lead to depression onset.

Our results suggest a bidirectional longitudinal association between depression and GID among middle-aged and older adults. Several potential biological mechanisms support that GID are risk factors for depression. First, GID can affect mental health through cellular and molecular pathways, such as oxidative stress, mitochondrial dysfunction, inflammation [27, 28]and HPA axis disorders in the endocrine system [27, 29]and a decrease in neurogenesis and BDNF levels in the nervous system directly affects the psychological process leading to depression [27]. Second, GID can induce changes in intestinal microorganisms, known as ecological disorders, and promote the onset and progression of depression by regulating the brain-gut axis [30, 31]. In addition, chronic visceral pain caused by inflammatory bowel disease and brain‒gut interactions might impose a heavy psychological burden on patients and lead to the occurrence of depression [32]. Moreover, several potential mechanisms have been proposed to support our findings that GID are related to depression. First, people with mental disorders often have poor health behaviors, such as smoking, a lack of physical activity and social participation, and unhealthy eating habits [33, 34]. These adverse factors may jointly promote the occurrence of GID. Second, depression and obesity are interdependent pathological diseases, and obesity changes the composition and metabolic activities of the intestinal microbiota [30, 33]. Changes in the intestinal microbiota are closely related to the occurrence of GID, especially inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) [35]. Third, the expression of the bacterial translocation marker 16 S rDNA in depression patients is greater than that in normal people, which induces endotoxin translocation and increases intestinal permeability [29]. Fourth, depression is associated with stressful experiences such as bad childhood experiences [36]. Physiological and psychological stressors may increase the levels of inflammatory biomarkers and stress hormones, which may act as a bridge between depression and gastrointestinal-related diseases [37].

By performing a three-wave cross-lagged analysis, we not only revealed the longitudinal bidirectional relationship between depression and GID among middle-aged and older adults but also revealed that GID status might play a greater role in driving their interactions. Although no prior research has directly assessed this bidirectionality and the relative strength of different directional pathways, existing studies offer supportive evidence for our findings. Specifically, earlier research suggested that physical health may be the primary driving force in the interaction between physiological function and brain health among middle-aged and older adults. For example, one study emphasized that slower gait speed could play a dominant role in the bidirectional gait-cognition relationship [38].

The hazard ratios obtained from Cox models carry notable clinical and public health implications. A 36% increased depression risk among middle-aged and older adults with GID suggests that improving gastrointestinal health management in this population could substantially reduce the population attributable fraction of depression. Assuming a causal relationship, effective management of GID in the 24.6% baseline prevalent cases could theoretically prevent approximately 9.6% of new depression cases based on population attributable risk calculations. Similarly, the stronger association between depression and newly reported GID highlights the importance of integrating mental health screening into routine gastroenterological care. These findings highlight the potential clinical relevance of monitoring mental health in gastroenterological settings and vice versa, though further intervention studies are needed to confirm the feasibility of such integrated approaches. At the policy level, this evidence supports the development of dual-prevention strategies under China’s National Elderly Health Promotion Guidelines, potentially reducing the compound disease burden through synergistic interventions.

Additionally, the stratified analyses and modification effect evaluation demonstrated significant heterogeneity in the bidirectional GID-depression associations across subgroups, with notable effect modification by sex and education level. Females exhibited consistently stronger bidirectional risks than males showed the most pronounced risks in both directions. Women are vulnerable to GID and depression, and their vulnerability may stem from factors such asneuroendocrine interactions between estrogen fluctuations and gut-brain axis regulation [39, 40]. Estradiol modulates both intestinal permeability through claudin protein expression and serotonin synthesis via tryptophan hydroxylase activation, potentially creating cyclical vulnerability during perimenopausal transitions [41]. Furthermore, gender-based caregiving burdens in Chinese households may compound chronic stress, exacerbating HPA axis dysregulation and systemic inflammation [42]. Individuals with higher educational attainment exhibited stronger bidirectional associations compared to those with lower educational attainment. While education typically confers protective health behaviors, heightened symptom awareness may increase somatic attribution of psychological distress. White-collar professionals also experience greater work-related stress than manual laborers [43]this elevated stress load suppresses vagal nerve activity, a key modulator of gut motility and inflammation [44]. Notably, Urban residents also had a significantly elevated risk of developing depression after GID compared to rural counterparts.and this difference may be attributed to the mediating role of social stressors in the process of urbanization. These findings offer a new foundation for targeted prevention and intervention strategies for these specific vulnerable groups.

This study has several strengths and novelties. First, the study filled the knowledge gap concerning the two-way longitudinal relationship between GID and depression in a specific group of middle-aged and older Chinese adults via a large-scale longitudinal cohort study design. Second, we used a Cox proportional hazards regression model to conduct two prospective unidirectional analyses for exploring different directional paths based on two subcohorts; at the same time, we also conducted cross-lagged analysis to further explore two-way relationships simultaneously. Although these two modeling strategies differ greatly in terms of design and bias sources, their consistent findings suggest the robustness of the bidirectional associations. In addition, our stratification analyses identified vulnerable populations for each directional pathway between depression and GID, which is crucial for informing preventive and interventional strategies.

However, several limitations of this study should be acknowledged. First, owing to unavailability of ICD code and GID subtype data, this study was unable to include all typical clinical data related to gastrointestinal diseases, including specific subtypes such as inflammatory bowel disease versus functional dyspepsia. While self-reported clinician diagnoses of GID in CHARLS have been validated in large-scale surveys [17]the lack of granularity in GID classification constrained our ability to explore heterogeneous associations between distinct pathologies and depression. Second, self-reported binary GID may also introduce misclassification bias. Underreporting could occur due to recall error or undiagnosed cases, while overreporting might arise from self-diagnosis without medical confirmation. Future studies are warranted to validate self-reported GID with medical records to mitigate these limitations. Third, despite employing longitudinal analysis to reduce unmeasured time-varying confounding, residual confounding persisted due to the observational study design. Fourth, although cross-lagged models identified bidirectional associations, causal inference remains limited-randomized controlled trials or advanced causal methods are needed to confirm the directionality of these relationships. Fifth, given that the event times in our study were interval-censored rather than exact, the interpretation of the hazard ratios from Cox PH models might not fully capture the precise effect estimates. Future research should explore more specialized models designed for interval-censored data. Finally, the exclusive inclusion of middle-aged and older Chinese adults restricts the generalizability of findings to other age groups and ethnic populations. These limitations highlight the need for future multiethnic cohorts with detailed GID subclassification to elucidate disease-specific mechanisms.

In summary, our findings indicate a longitudinal, bidirectional association between gastrointestinal disorders and depressive events among middle-aged and older individuals in China. This newly identified bidirectional association suggests that interventions targeting either gastrointestinal health or depression may offer reciprocal benefits over time, potentially promoting healthy aging. Furthermore, the cross-lagged path coefficients imply that gastrointestinal health could be the stronger driving force in its dynamic interaction with depression. Future research is needed to confirm this longitudinal bidirectionality and explore the potential biological and behavioral mechanisms involved.

No datasets were generated or analysed during the current study.

- GID:

-

Gastrointestinal disease

- CLPMs:

-

Cross-lagged panel models

- CHARLS:

-

The China longitudinal study of health and retirement

- IBS:

-

Irritable bowel syndrome

- PUD:

-

Peptic ulcer

- FD:

-

Functional dyspepsia

- IBD:

-

Inflammatory bowel disease

- GERD:

-

Gastroesophageal reflux disease

- NAFLD:

-

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease

We acknowledge the CHARLS for providing the data.

The CHARLS study received ethical approval from the Beijing University Biomedical Ethics Review Board (IRB00001052-11015), and all participants provided written informed consent. The study methodology was carried out in accordance with approved guidelines.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Guo, J., Su, M., Huang, J. et al. Longitudinal bidirectional association between gastrointestinal disease and depression symptoms among middle-aged and older adults in China. Arch Public Health 83, 171 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-025-01671-8

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13690-025-01671-8