Breast Cancer Research volume 27, Article number: 117 (2025) Cite this article

Weight gain during chemotherapy is frequently reported in breast cancer patients and adversely impacts survival and quality of life. However, weight change over the long term and its determinants in breast cancer patients who received chemotherapy remain unclear. This study aimed to characterize weight change over 13 years among French breast cancer patients diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer who received adjuvant chemotherapy.

We examined weight change over 13 years in a cohort of 267 early breast cancer patients diagnosed between 2004 and 2006 and treated with adjuvant chemotherapy. Yearly weight measures were obtained from medical records, or from questionnaires when not available from medical records. We compared weight at each time using analysis of variance for repeated data based on mixed-effect models, and examined clinical and individual factors as potential determinants of weight change over the study period.

More than one third of women experienced weight gain > 5% of their initial body weight following initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy (34.6%, 36.0%, 41.6%, and 37.4% at years 1, 5, 10, 13, respectively). A statistically significant weight gain occurred during the first year after initiation of chemotherapy (estimated mean gain: 1.80 kg; 95% confidence interval (0.52–3.1) kg) and was maintained for up to 13 years (P-value for overall effect of time on weight < 0.001). This weight gain was observed only for women with an initial BMI < 25 kg/m². Type of chemotherapy, use of hormone therapy, age at inclusion, menopausal status, or physical activity level at initial visit did not show statistically significant association with weight change.

These results emphasize the need to improve our understanding of weight change and its determinants and to develop effective intervention strategies to prevent weight gain for breast cancer patients during the first year of treatment.

Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women worldwide, with almost 2.3 million new cases in 2022 [1]. Although 5-year net survival rates reach 90% in high-income countries [2], prognosis varies according to individual and clinical characteristics, such as age, stage, grade, molecular subtypes, and treatments. Obesity and postdiagnosis weight gain also impact prognosis and have been consistently associated with lower overall and breast cancer-specific survival [3, 4], with emerging evidence towards an increased risk of cardiovascular diseases as well [5]. Besides, weight gain perceived as a side effect of treatment impacts quality of life [6] and could lead to decreased therapeutic adherence [7, 8]. Therefore, there is a strong need to prevent postdiagnosis weight gain in the growing population of breast cancer patients.

Weight gain is a common issue experienced by 50–96% of breast cancer patients who received chemotherapy, although this proportion tends to decrease with current treatments [6, 9]. Indeed, evidence is particularly consistent towards chemotherapy-associated weight gain, with early-stage breast cancer patients experiencing an average 2.7 kg weight gain during chemotherapy [9], despite heterogeneity between studies. Given that up to half of early-stage breast cancer patients are treated with chemotherapy [10, 11], the identification of women at high risk of weight gain is crucial to provide appropriate management and improve tertiary prevention strategies.

However, some methodological challenges have limited our understanding of chemotherapy-associated weight gain so far. Most studies have used weight measurements at two or few time points only [12,13,14] rather than providing a longitudinal repeated follow-up of weight that can help identify critical periods of weight change trajectories [13, 15, 16]. Also, the time frame of interest varied considerably between studies, and was most often limited to a maximum of 5 years after diagnosis [12, 13, 15], which does not allow the examination of weight changes that may persist after the end of cancer treatments, including endocrine therapy that may also impact weight change [17].

Additional factors could modulate chemotherapy-associated weight gain. In addition to treatment type, a younger age [15, 18,19,20,21,22] or premenopausal status [6, 23,24,25] at diagnosis have been associated with a greater weight gain in breast cancer patients in several studies, but not all [9, 26]. Postdiagnosis weight change may also differ according to body mass index (BMI) at diagnosis, although studies have reported either non-significant [23, 25, 26] or inconsistent associations, with greater weight gain observed either for lower [15, 19, 24, 27, 28] or higher [16, 21] BMI ranges at diagnosis. Besides, other energy balance-related factors such as diet and physical activity have been investigated in a limited number of studies [6, 29], showing for instance a greater weight gain among breast cancer patients who decreased their level of physical activity after cancer diagnosis [28, 30]. Overall, determinants of postdiagnosis weight gain in breast cancer patients remain debated, especially over the long term.

Hence, this study aimed to describe weight change over 13 years among French breast cancer patients diagnosed with early-stage breast cancer who received adjuvant chemotherapy, and to investigate potential determinants of long-term weight changes in this population.

An observational cohort of French breast cancer patients treated at the Léon Bérard Cancer Center (Lyon, France) was followed up for 13 years [14]. Inclusion criteria were: age ≥ 18 years, having undergone surgery for a histologically confirmed localized breast cancer between 2004 and 2006, and being a suitable candidate for adjuvant chemotherapy. Patients were ineligible if they had distant metastases or prior history of cancer, or if they were unable to understand the information provided. Data collection was performed in accordance with the French National Committee on Informatics and Privacy (CNIL) regulations. Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

At inclusion, participants completed a baseline visit before initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy. Weight (in kg) and height (in cm) were measured by trained staff and were used to derive baseline BMI in kg/m². Clinical information on tumor type (lymph node invasion, tumor size, hormone receptor status) and treatment (type of chemotherapy, endocrine therapy) was extracted from medical records. Menopausal status was assessed clinically (12 months with no menstrual flow at all) at baseline and updated in 2012, which allowed to distinguish between women who were postmenopausal before initiation of chemotherapy, women whose menopause was induced by chemotherapy (defined as 12 months without menstrual bleeding or spotting after end of chemotherapy), and women who remained premenopausal after end of chemotherapy.

A questionnaire was administered by a dietician to collect information on physical activity, personal history of diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, hypertriglyceridemia, and menopausal status. Level of physical activity was considered high if the patient performed the equivalent of at least half an hour of brisk walk per day and daily life or professional activities, medium for less than half an hour of brisk walk per day and/or taking care of house chores, or low otherwise if the patient was autonomous at home without any physical activity [14].

During follow-up, weight was updated from three sources of information. When available, weight was abstracted from patients’ medical records. Incomplete data were updated on two occasions. In 2012, patients with missing follow-up data received a questionnaire, followed by a standardized phone interview administered by two dieticians and a medical resident to update patients’ weight and menopausal status. In 2019, a self-administered questionnaire was sent to women asking them to recall their weights each year from 2011 to 2019.

Patients’ characteristics were described using means and standard deviations for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables.

Weight (in kg) was analyzed as a continuous variable, and relative weight change compared to initial weight (assessed at baseline visit) was estimated and expressed as a percentage. Relative weight change of less than 5% of initial weight was categorized as stable weight. An increase of 5% or more of initial weight was considered a clinically relevant weight gain, with 5–10% gain considered as moderate and > 10% considered as severe, while a decrease of 5% or more was defined as weight loss [3, 4, 6, 22, 31].

We first conducted exploratory descriptive analyses of weight and relative weight change (using means and standard deviations) and relative weight change categories (using frequencies) at years 1, 5, 10, and 13 of follow-up.

To estimate the effect of time on weight, analysis of variance for repeated data was performed. Mixed-effect linear models were built with weight as the dependent variable and a random intercept for each subject. Time was included in the model as a categorical variable (Year 0 to Year 13) to better capture the evolution of weight over time allowing for non-linear associations. Analysis of variance using Wald F-test was performed to evaluate the overall effect of the time variable in the model. Adjusted means were estimated at each time with their 95% confidence interval, and post-hoc pairwise comparisons were performed to estimate weight difference (in kg) across different times with Tukey adjustment of P-values. Type of chemotherapy (anthracyclines only or taxanes alone/combined with anthracyclines), use of endocrine therapy (yes/no), age at inclusion (≤ 55 years/>55 years), menopausal status (postmenopausal/ chemotherapy-induced menopause/ premenopausal), BMI at initial visit (< 25 kg/m², 25–29.9 kg/m², ≥ 30 kg/m²) and physical activity level at initial visit (low, medium, high) were examined as potential determinants of weight change. These categorical variables were studied in separate models by adding an interaction term between time and each variable and obtaining the P-value corresponding to this term. Initial mean weight (kg) in each category of the investigated factor was estimated with its 95% confidence interval, and mean absolute differences between weights at year 1, year 5, year 10 and initial weight were estimated in each category of the investigated factor. When a significant interaction between the studied factor and time was detected, intra-group analysis was performed to evaluate the effect of time in each group, and mean weight and 95% confidence interval was estimated at each time for each category of the variable. All models were adjusted for age at inclusion (continuous) and disease severity with tumor size (< 20 mm/20–50 mm/>50 mm) and lymph node involvement (yes/no), as potential confounders.

As a sensitivity analysis, self-reported weight one year before diagnosis was used as baseline weight instead of measured weight at diagnosis, to examine the effect of potential pre-diagnosis weight changes.

All statistical tests were two-sided. All statistical analyses were performed using R 4.2.2.

A total of 267 women were included in our analysis. Patients were on average 51.0 years old at inclusion; 60.4% were postmenopausal before initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy while menopause was induced by chemotherapy in 25.5% (Table 1). Lymph node invasion was reported in 67.6% of patients, with 74.2% of tumors being estrogen receptor-positive and 62.5% progesterone receptor-positive. Most patients (78.2%) received endocrine therapy and more than half (51.5%) received taxane-based chemotherapy in combination with anthracyclines. The majority of patients (58.8%) had a normal BMI at inclusion, and one third (33.0%) had a low level of physical activity. Weights were mostly obtained from medical records up to the Year 7 (Supplementary Table 1, Additional File 1).

At baseline, mean weight was 66.0 kg (SD: 12.6 kg) (Table 1). After one year (Table 2), mean weight increased to 67.9 (± 13.9) kg, corresponding to a relative weight change of + 2.4 (± 7.0) % on average, with 34.5% of women experiencing weight gain greater than 5% of their initial weight. The average weights were 67.4 (± 13.3) kg, 66.2 (± 11.9) kg, and 65.9 (± 11.1) kg at 5, 10, and 13 years of follow-up, respectively, with an average relative weight gain of 2.4 to 3.1% of initial weight. Of note, among the 107 patients included at both year 0 and year 13, mean weight at baseline was 64.6 kg (not tabulated). The proportion of women who maintained a stable weight decreased from 55.1% at one year, to 46.7% at five years and 40.0% at ten years, and was 45.8% at year 13. Weight gain (moderate and severe) was more prevalent (34.6%, 37.1%, 41.6%, and 37.4% at years 1, 5, 10, 13, respectively) than weight loss at all times (10.3%, 17.6%, 18.4%, 16.8% at years 1, 5, 10, 13, respectively). After one year, moderate weight gain (5–10%) was overall more frequent than severe weight gain (moderate: 23.8%, severe 10.7%), except among women with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m² (moderate 12.1%, severe 18.2%). At year five, the prevalence of severe weight gain almost doubled overall (reaching 19.8%) and in women with a BMI < 25 kg/m² (reaching 20.5%) and 25–30 kg/m² (reaching 17.3%). Women with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m² experienced an average relative weight loss from year 5 (year 5: -0.5%, year 10: -0.7%, year 13: -3.1%), although number of patients in this category was limited.

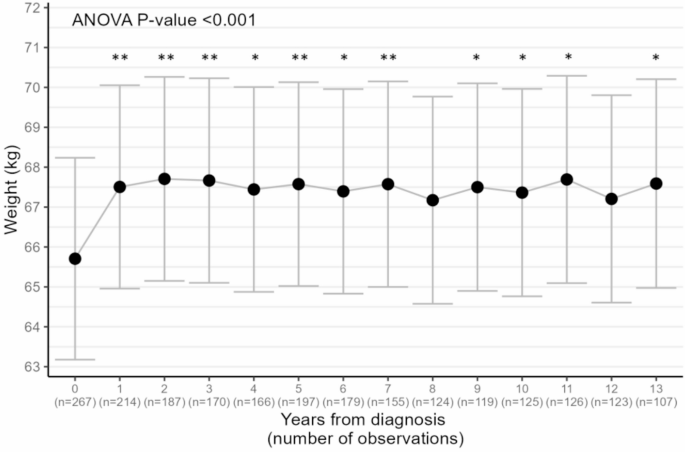

Based on analysis of variance (Fig. 1), weight change was statistically significant over time (P-value < 0.001), with an estimated increase in weight during the first year of 1.80 (0.52–3.1) kg. Pairwise comparisons of estimated means across times showed statistically significant differences between all times (except year 12 and year 8) and initial weight, while other pairwise comparisons of estimated mean weights did not highlight differences between specific times.

Estimated mean weights and 95% confidence interval during 13 years after diagnosis (N = 267). Adjusted means and global ANOVA P-value for time were obtained from mixed-effect linear models with weight as the dependent variable, random intercept for each subject, and fixed effects for time and age (continuous), maximum tumor size (< 20 mm/20–50 mm/>50 mm), and lymph node involvement (yes/no). Stars indicate statistically significant difference from initial weight after Tukey adjustment of P-values in pairwise comparisons (*<0.05; **<0.001)

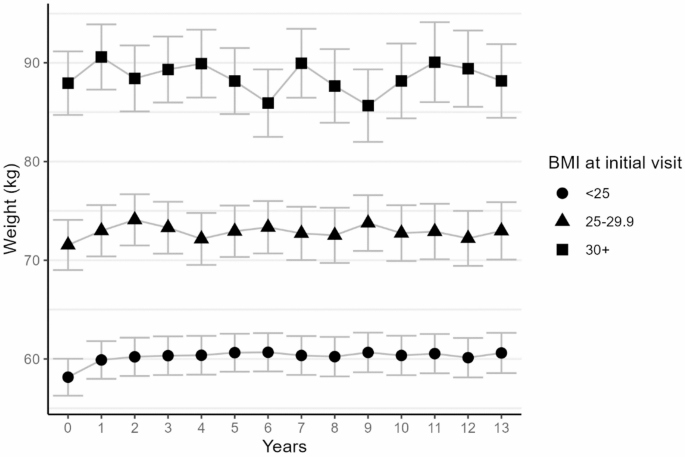

Initial body mass index was the only variable showing a statistically significant association with weight change over time (P-valueBMI*time interaction=0.007, Table 3). Estimated absolute weight gains of 1.75 95% CI (-0.18–3.67) kg, 2.48 (0.51–4.46) kg, and 2.20 (-0.03–4.43) kg at years 1, 5, and 10 were observed for women with an initial BMI < 25 kg/m², that was lower in those with a BMI between 25 and 30 kg/m² (1 year: 1.44 (-1.46–4.34), 5 years: 1.39 (-1.54–4.33), 10 years: 1.20 (-2.46–4.86)) and in those with a BMI ≥ 30 kg/m² (1 year: 2.65 (-1.21–6.51), 5 years: 0.21 (-3.81–4.22), 10 years: 0.22 (-5.16-5.59)), as shown also on Fig. 2. Intra-group analysis of variance indicated a statistically significant association between weight and time among normal weight women only (BMI < 25 kg/m²: P-value < 0.001; 25–30 kg/m²: P-value = 0.23; ≥30 kg/m²: P-value = 0.29; not tabulated). Weight change over time did not significantly differ according to type of chemotherapy, use of endocrine therapy, age at diagnosis, menopausal status, or physical activity level at initial visit (all P-values for interactions with time ≥ 0.31, Table 3).

Estimated weights over time by initial BMI category (adjusted means and 95% confidence intervals). Adjusted means were obtained from mixed-effect linear models with weight as the dependent variable, random intercept for each subject, and fixed effects for time and age at inclusion (continuous), maximum tumor size (< 20 mm/20–50 mm/>50 mm), and lymph node involvement (yes/no)

When considering self-reported weight one year prior to diagnosis as baseline weight in the analysis of variance, results remained unchanged with an estimated gain of 1.70 (0.36–3.03) kg gain at year 1.

In this cohort of early breast cancer patients who underwent adjuvant chemotherapy, more than one third of women experienced weight gain following initiation of chemotherapy. Thanks to the long follow-up, we observed that a significant weight gain occurred during the first year after initiation of chemotherapy and was maintained for up to 13 years. A statistically significant weight gain was observed only for women with an initial BMI < 25 kg/m², but remained non statistically significant for other BMI categories. Type of adjuvant chemotherapy, use of endocrine therapy, age at diagnosis, menopausal status, or physical activity level at initial visit were not associated with weight change.

A 2017 meta-analysis investigating weight change during chemotherapy in localized breast cancer patients [9] showed an average weight gain of 1.9 (95% CI: 1.3–2.5) kg in studies published after 2000, in line with the estimated mean gain of 1.8 kg we report during the first year of follow-up. Our results suggest that weight gained during the first year is maintained over the long term. While no previous study provided such a long follow-up, a cohort of breast cancer patients from Taiwan showed that 2 years after chemotherapy, patients had still not returned to their initial weight [32]. A similar trend was observed in two studies with a follow-up of five years - a Dutch study of breast cancer patients who underwent combined chemotherapy and endocrine therapy [13], and a large US-based study among women who underwent chemotherapy [15] - as well as among women of the Women’s Healthy Eating and Living (WHEL) study with a follow-up of up to 6 years [33]. Whether weight gain in breast cancer patients is greater than in women without breast cancer is not established. Indeed, weight gain is also commonly observed in midlife women [34]. After two years, women with early invasive breast cancer (n = 362) were more likely to gain weight after surgery than age-matched women without a history of breast cancer [35]. In addition, a study of women at familial risk of breast cancer indicated that over four years, breast cancer survivors (n = 303), especially those within five years of their diagnosis, tended to gain weight at a faster rate than cancer-free women [36]. In contrast, two older studies showed no statistically significant difference in weight gain at 6 months (n = 20 patients) [37] and 6 years (n = 305 patients) [38] in women with and without breast cancer. A specificity of chemotherapy-associated weight gain might be its rapid rate. Indeed, the magnitude of weight gain we report during the first year (2.4% on average) is similar to that reported over intervals of several years in cancer-free women [39, 40]. For instance, the Study of Women’s Health Across the Nation showed a linear increase in weight with an annual gain of 0.45–0.50% before menopause, that slowed after menopause, accompanied with rapid changes in body composition at the time of menopause [41]. Therefore, further research is needed to elucidate weight gain in breast cancer patients as compared to age-matched women without breast cancer, especially since rapid weight gain may be accompanied with greater negative metabolic alterations, and body composition changes may also differ between these women.

The prevalence of weight gain of 34.6% we report at one year is consistent with previous studies [9], such as a US-based study reporting a weight gain greater than 2 kg in 35% of patients after two years [23]. In contrast, in the Multi Ethnic Cohort (MEC), weight gain of more than 5 lbs (2.3 kg) affected at most 14% of patients who underwent surgery and chemotherapy [16]. In this population however, weight loss was more common than weight gain, which could be related to an average age at surgery of 71.0 years (versus 51.0 years in the present work). While it was earlier hypothesized that water retention during chemotherapy contributes to short-term weight change [12], the persistency of weight gain observed by us and others points more towards durable modifications of energy balance, that could be related to metabolic changes, increased fatigue, or taste change [42,43,44], resulting in reduced physical activity and/or changes in diet during chemotherapy. Changes in the gut microbiome occurring during chemotherapy could also contribute to such weight gain [45].

We did not observe any statistically significant difference between chemotherapy regimens used in our population– mainly anthracyclines alone or in combination with taxanes. Previous studies pointing at differences in weight gain by chemotherapy type have mostly focused on regimens based on cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil (CMF) versus others, showing an increased weight gain with CMF versus non-CMF regimens [9], with for instance an increased weight gain over 2 years in Taiwanese patients who received CMF regimens as compared with anthracyclines [32]. Fewer studies have distinguished between more recent chemotherapy regimens. In the study by Nyrop et al.., any type of chemotherapy was associated with an increased risk of weight gain [23], as in the WHEL study that included a control group without chemotherapy or endocrine therapy [33], in which risk of weight gain was increased for all types of chemotherapy regimens, combined or not with endocrine therapy.

In our population, endocrine therapy in addition to chemotherapy did not modify weight change. This could be related to limited statistical power to explore weight change in non-users of endocrine therapy, given the relatively low proportion of non-users, but the impact of endocrine therapy on weight gain remains overall unclear [12, 17]. In the WHEL study, endocrine therapy alone was not associated with an increased risk of weight gain [33], as outlined by a 2016 literature review [17], in line with results from the Young Women’s Breast Cancer Study [31]. In contrast, Nyrop et al.. reported a decreased weight gain for endocrine therapy use versus non-use, especially for aromatase inhibitors (AI) only [23]. Given changes in use of endocrine therapies over the last years [46], for instance ovarian suppression with AI for high-risk premenopausal women [47], a more detailed investigation of treatment types and combinations is needed.

We did not identify age or menopausal status as modifiers of weight change in our population. This result contrasts with most existing literature [6, 12, 15, 18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25], but the role of menopausal status as a predictor of weight gain remains unclear. Indeed, in a cohort of young breast cancer patients in the US [31], menopausal transition was not associated with weight gain. A 2018 study in women with hormone-receptor positive breast cancers showed that associations of premenopausal status with risk of weight gain disappeared after adjustment for tumor characteristics [26], suggesting that increased risk of weight gain for premenopausal women could be driven by greater breast cancer severity in these patients. Still, other large studies such as the one by Puklin et al. [15]. have highlighted differences by age group (with opposite weight change in extreme age groups) even after accounting for disease severity. A general hypothesis is that weight gain during chemotherapy could be mostly driven by chemotherapy-induced amenorrhea [6]. We were able to study women who experienced menopausal transition during chemotherapy as a separate group, as well as premenopausal women who remained premenopausal after chemotherapy, but we surprisingly did not observe any difference by group of menopausal status, nor by age. While limited statistical power cannot be ruled out, in particular among the group of premenopausal women, our results do not support the current hypothesis regarding a major role for chemotherapy-induced change in ovarian function in post-diagnosis weight gain, although this association remains complex.

In our work, women with a BMI < 25 kg/m² experienced a significant absolute weight gain, while in patients with a BMI > 30 kg/m², there was a non-statistically significant trend towards a relative weight loss. Although it is not clear why women with a normal BMI are more likely to gain weight, these findings align with several previous studies in breast cancer patients [15, 19, 24, 27, 28, 31] and highlight the role of initial weight status as a potential predictor of weight gain during treatments, which could therefore help identify women with a higher risk of weight gain. Given the recent development in weight-loss medications, which may impact weight change trajectories among overweight and obese women, their use warrants further investigation in future studies.

In the present work, level of physical activity at initiation of chemotherapy was not associated with weight change over time. A recent study among US Black breast cancer survivors [28] highlighted that change in physical activity from 10 to 24 months after diagnosis was associated with weight change, supporting results from the early Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle (HEAL) study [30] that showed an association between decreased levels of sports/recreational physical activity from diagnosis to 3 years and weight gain. Consequently, change in physical activity that may occur during or after chemotherapy may be more important than initial level of physical activity. Besides, future research in overweight and obese patients should also consider changes in dietary habits at the time of chemotherapy.

A unique strength of our study is the follow-up over 13 years, which allows for the first time to our knowledge, the ability to examine long-term weight change years beyond the end of cancer treatment, including endocrine therapy. Besides, information available on a wide range of clinical and patients’ characteristics allowed us to examine whether weight change differed according to various factors, including menopausal status and type of menopause (chemotherapy-induced or not). A first limitation of this work was the use of multiple sources of information to collect weight at different times. Although the preferred and main source was medical records, self-recalled weight obtained from patients to complete data may have been biased related to memory or social desirability [48,49,50,51] and could have artificially limited or exaggerated weight variations. While information was collected at baseline on important variables such as physical activity, data were not regularly updated during follow-up which prevented us from accounting for changes in levels of physical activity frequently reported in breast cancer patients [52]. In addition, more than half of participants were missing at the last evaluation, which may have limited statistical power to detect associations over the long term, especially regarding potential determinants. Therefore, some subgroups of potential determinants were relatively small, and estimates of weight changes across categories should be interpreted with caution given their wide confidence intervals. Lastly, changes in body composition such as muscle loss may occur even for a relatively stable weight and could impact patients’ survival differently [53]. In this clinical cohort, no specific exams were performed to evaluate body composition, and although methods developed to automatically derive body composition from routinely performed exams such as CT-scans are being developed [54, 55], most patients in this cohort had a CT-scan performed at diagnosis only, which did not allow us to evaluate evolution of body composition.

In early breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy, a significant weight gain was observed during the first year following initiation of chemotherapy, which persisted over 13 years. This result emphasizes the need to monitor and limit weight change over the course of cancer treatments, and especially during chemotherapy, by developing effective prevention strategies for breast cancer patients.

The datasets used and/or analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

- BMI:

-

Body mass index

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- CMF:

-

Cyclophosphamide, methotrexate, and fluorouracil

- HEAL:

-

Health, Eating, Activity, and Lifestyle study\MEC Multi ethnic cohort

- MEC:

-

Multi ethnic cohort

- WHEL:

-

Women’s Healthy Eating and Living study

The authors wish to thank Aurélia Maire, Ariane Suc, and Marina Touillaud, as well as oncologists involved in patients’ follow-up, and patients, for their important contributions to this work.

None to be declared.

The database collected for this study was approved by the French National Committee on Informatics and Privacy (CNIL). Informed consent was obtained from each patient.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

His, M., Baggio, I., Chabaud, S. et al. Long-term weight change among breast cancer patients treated with chemotherapy: a longitudinal study over 13 years. Breast Cancer Res 27, 117 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-025-02079-6

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s13058-025-02079-6