Inside Nigeria's booming wildlife trade: Harrowing ordeal of zoonotic disease survivor | TheCable

What started as a mild fever just weeks before Christmas Day, quickly spiraled out of control leading to kidney failure, blurry vision and months of dialysis.

Despite being given a cocktail of typhoid and malaria drugs, his condition only worsened until he was finally rushed to a hospital.

Olanrewaju, a native of Osun, had lived all his life in North Bank, a sparsely populated community in Markurdi, Benue state, known as Nigeria’s food basket due to its vast farmlands and agricultural bounty.

When he eventually got to the hospital, doctors continued treating him for malaria — till the night he vomited blood. That moment changed everything.

Olanrewaju’s blood sample was quickly sent to Abuja for testing, and it was there that the true cause of his illness was finally uncovered. It was indeed Lassa fever.

With the diagnosis confirmed, he was instantly transferred to the in Abakaliki, Ebonyi state, one of the few specialised centers equipped to handle such cases in Nigeria.

There, his condition remained critical, and he required over 10 pints of blood, weeks of dialysis, and intensive care just to stay alive.

“I treated typhoid for about a month and a half. Each time I took the drugs, I’d feel strong for a while. But every night, my temperature would rise,” Olanrewaju recounted.

“The night I vomited blood at the hospital, the doctor asked if I was a smoker; I said no. That was when they took a blood sample and sent it to Abuja for testing. It came back positive for Lassa fever.”

In the white isolation room echoing with beeping machines, Olanrewaju recalled the chilling sight of a fellow patient convulsing as blood streamed down his eyes till he gave up the ghost — the harrowing final stage of Lassa Fever.

Lassa fever symptoms usually start gradually, with fever, weakness, sore throat, and stomach issues that mimic malaria or typhoid.

While many recover without diagnosis, about 1 in 5 become severe, leading to bleeding, breathing problems, confusion, and organ failure. In the worst cases, patients go into shock and, without urgent treatment, may die.

Amid the endless medications and the discomfort of tubes and machines, the once vibrant teenager found himself cut off from the world, entirely at the mercy of doctors and nurses cloaked head to toe like astronauts on a mission to the moon.

Their faces hidden behind shields, and their movements were very clinical and precise, as the medical officials hovered around him, trying to keep him alive.

“I was completely cut off. No family, no familiar faces. I didn’t even know who was treating me,” Olanrewaju said.

“In that isolation ward in Abakaliki, I watched a man bleed from his eyes and die. That was when I knew this thing was real.”

At the isolation center, time lost meaning. There were no phones, no family visits, nor comforting voices — only the steady beep of machines and the muffled footsteps of people he could not recognise.

Olanrewaju had made it past the 10-day treatment threshold, the critical period where many victims don’t.

But that was only the beginning of his trauma, distrust, as he was greeted soon enough with the aching news of the demise of his uncle who had taken him to the hospital that night.

While Olanrewaju believes he may have contracted the virus through contaminated garri, the scars of the disease still lies within him.

“The infection had already contaminated my blood, and then it started affecting my organs. My kidney failed,” he said.

“I had to undergo dialysis, and they had to change my blood. I received a lot of transfusions — over 10 pints of blood. At some point, I couldn’t walk and I was in a wheelchair all through my stay at the hospital.”

Now 18, Olanrewaju studies Political Science at Benue State University, but his eyes carry the weight of someone who has stood at the edge of life.

The trauma lingers, not just from the illness itself, but from the isolation that followed, the friends who deserted him during his darkest hours, and even now, a quiet stigma of being a survivor trails behind him.

Olanrewaju’s case reflects a wider public health challenge in Nigeria, where zoonotic diseases like Lassa fever are often due to a health system geared toward more familiar illnesses like malaria.

Zoonotic diseases (Zoonoses) are infectious illnesses transmitted from animals to humans, usually caused by a variety of pathogens, including viruses, bacteria, and parasites.

They are transmitted to humans either through direct contact with animals, consumption of contaminated food and water.

According to the (WHO), about 60 percent of known infectious diseases in humans are zoonotic, and up to 75 percent of emerging infectious diseases have an animal origin.

This data underscores the ongoing risk zoonoses pose to global health — especially as human activities increasingly encroach on wildlife habitats, disrupting natural ecosystems and creating more opportunities for spillover events.

The consequences of zoonotic diseases have been both deadly and disruptive in Nigeria.

In 2014, the country was rocked by an outbreak said to be caused by fruit bats, after an infected Liberian man arrived in Lagos — Africa’s most populous city.

The was swiftly contained within 93 days, resulting in only 20 confirmed cases and 8 deaths.

Lassa fever, another zoonotic disease caused by the Lassa virus and transmitted primarily through contact with food, household items contaminated by the urine or feces of infected multimammate rats — a common rodent in West Africa — remains a persistent and far more complex threat in the country.

This viral hemorrhagic illness was first in Nigeria in 1969.

While it is endemic in the country (reoccuring), it typically during the dry season (November to April). However, in severe cases, it can to multi-organ failure, internal bleeding, and death.

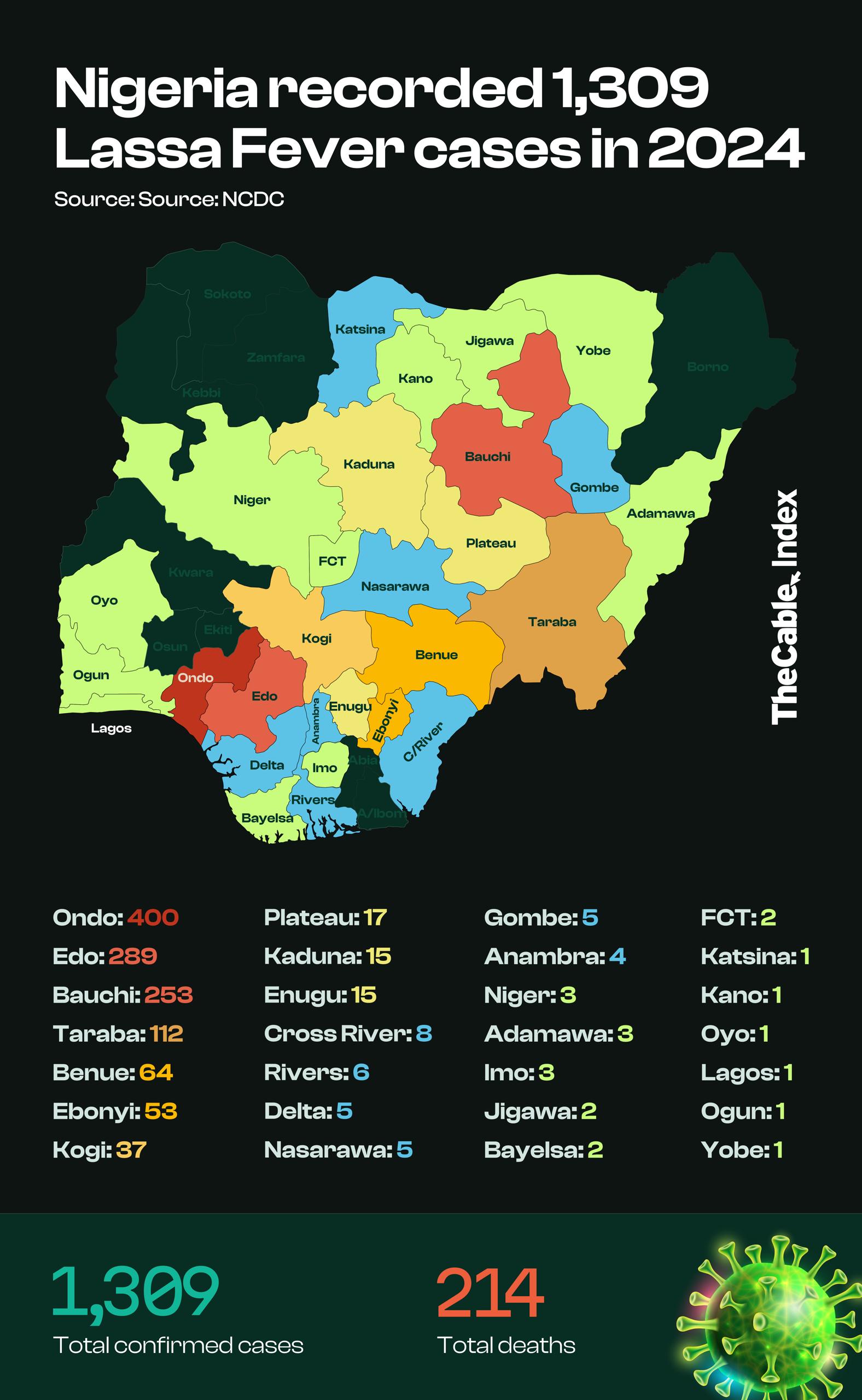

According to the (NCDC), the country recorded 1,309 confirmed cases of Lassa fever and 214 deaths in 2024, with a fatality rate of 16.4 percent.

Ondo state led with 400 and 27 deaths, followed by Edo with 289 cases and 30 deaths.

Another re-emerging zoonotic threat in Nigeria is Mpox, formerly known as monkeypox.

Caused by the monkeypox virus, the disease is from animals such as rodents or monkeys to humans, and also spreads between people through close physical contact.

Nigeria experienced a of Mpox in 2017, nearly four decades after its last reported case in 1971.

Since then, the country has hundreds of infections with symptoms such as fever, swollen lymph nodes, and painful skin lesions.

Globally, the most devastating zoonotic event in recent history was the COVID-19 pandemic, by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), believed to have originated from a zoonotic spillover from an animal market in Wuhan, China.

In Nigeria, the pandemic left a heavy toll, with over 250,000 cases and more than 3,000 deaths recorded so far. In 2024 alone, there were 804 confirmed COVID-19 cases with one death.

The outbreak of the virus disrupted nearly every aspect of life in Nigeria and across the world for more than two years, from healthcare and education to the economy and travel.

It was a muggy Monday morning in , one of the largest bush meat hubs in Nigeria, tucked away in the Lekki-Epe corridor of Lagos.

Cradled by the waters of the , the market is situated on Ajilogbo street, off the main road in Epe area of the state.

Boats ferrying goods and passengers from Ijebu Ode in Ogun state, and other riverine communities along the shoreline, were hastily unloading wares before sunrise. One wouldn’t help but notice a marine police post which stood quietly nearby, watching over the activities of the area like a sentinel.

Despite the official signpost that reads ‘Oluwo Modern Fish Market: Epe Terrestrial and Aquatic Hub‘, this open-air market thrives on something far more primal than fish — bush meat.

There were no men selling the commodity. Every stall was run by women who were all busy gutting, skinning, smoking, or slicing their catch which ranged from crocodile, grasscutter, tortoise, snakes, and even monitor lizards.

Suliyat Salaudeen was seated at her wooden stall, strategically de-feathering a freshly hunted porcupine as her hands moved with practised ease, unfazed by the spines.

She looked up at intervals, with sweat streaking down her brow, as she responded to this reporter’s unending questions.

The air in her stall hung thick with the smell of firewood and smoked animal fur. With a confident smile, Salaudeen said she has been selling bush meat in the market for more than 14 years.

“It’s been more than 14 years since I’ve been selling here. It’s like a family business; it was handed down to me. I sell grasscutters, porcupines, bush pigs, and snakes,” Salaudeen told TheCable.

Around her, slabs of bush meats hung from hooks while some rested on wooden tables stained with years of smoke, waiting for the next buyer.

She acknowledged that she no longer sells pangolins, following the government’s ban on the species due to its protected status.

Despite growing awareness about zoonotic risks and conservation laws, the trade remains brisk and largely unregulated.

“We no longer sell pangolins. Now it’s grasscutters, porcupines, antelopes, and snakes we sell,” she added.

“Our mothers handed us this work. They trained us through bush meat. Now I’m training my own children with it.

“It would be very painful for the government to ask us to stop selling bush meats. I’m feeding my children, paying school fees through this business. If they ban it, will they give us N500,000 every day to survive? Instead of banning it, they should help us advertise so we can sell faster.”

Just beside her stall, Idowu Oyedele, another seasoned trader, was busy fanning a charcoal pit where hunks of meat smoked slowly over low flames as she rearranged a pile of slightly burnt grasscutters.

Her stall, like many others, had no refrigerator, just plastic drums for storing water and baskets.

Oyedele said she is training a child in the university through her bush meat trade, adding that a grasscutter — which is her best seller — could go as low as N20,000 each.

She said although the traders lack water in the market, she tries her best to maintain high level of hygiene while preparing the meat.

According to her, the market is largely dominated by women because the demanding task of gutting and cleaning the animals is considered a domestic chore, often seen by men as a woman’s responsibility.

“Hunters usually bring the meat for us to sell. A grasscutter goes for ₦20,000, and a porcupine is ₦15,000,” Oyedele said.

“They can’t say we should not sell bush meat. This is what we use to feed our children. We’re not careless. We wash our hands and we use hand gloves.”

According to a by WildAid, about 51 percent of urban bushmeat consumption is influenced by taste and flavour. This craving, however, comes with hidden risks — especially in regions where zoonotic diseases like Lassa fever and mpox are on the rise.

Notably, none of the women in the market acknowledged the possibility of contracting infections from handling or consuming bush meat.

Instead, they defended the trade passionately, citing generational survival and their good health as proof that the meat was safe.

“Bush meat is good meat. There’s no sickness in bush meat. Look at us. We’ve been doing this since we were small. My body is still fresh,” Oyedele noted.

Beyond the clatter of machetes and the crackling of roasting fur, deeper challenges simmer beneath the surface of Oluwo Market.

At the edge of the market, traders had turned a section of the river into a makeshift holding pond, with baskets of live fish tied to an abandoned boat swaying gently on the murky water. It was a creative yet desperate attempt to keep their stock alive without refrigeration.

Sunday Adeeko, the general youth coordinator of the market, decried the lack of basic infrastructure.

He said traders spend thousands of naira daily just to purchase clean water for essential activities, from washing meat to using the toilet.

“There’s no water here, even to flush the toilet,” Adeeko told TheCable.

Adeeko noted that if the market had a reliable water supply, solar panels, and a functional generator, it would drastically reduce health risks and help modernise the place.

He called on relevant stakeholders to provide a cold room, solar electricity, and a dedicated generator to meet the market’s growing needs.

“We need solar, a cold room, and a generator set, to properly preserve our fresh meat and fish,” he added.

Nigeria has taken decisive steps to protect its biodiversity, from international treaties to launching national action plans against illegal wildlife trade.

The country boasts of extensive that serve as habitats to diverse species of wildlife, fauna and floras.

Global agreements like Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species of Wild Fauna and Flora (CITES), and National Biodiversity Strategy and Action Plan (NBSAP), which Nigeria is a , mandates the country to protect its endangered species — including pangolins, Cross River gorilla, and African grey parrot — from illegal trade and habitat loss.

These laws fall under the oversight of agencies like the Nigeria Customs Service, National Environmental Standards and Regulations Enforcement Agency (NESREA), park rangers, and non-governmental organisation’s (NGOs) including Nigeria Conservation Foundation (NCF) and the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS), which work to curb bush meat dependency and promote sustainable livelihoods.

Recently, the passed its third and final reading in the house of representatives.

If passed into law, the bill will strengthen Nigeria’s response to serious and organised wildlife trafficking and introduce stricter penalties for wildlife crimes.

Stella Egbe, senior conservation manager at the Nigerian Conservation Foundation (NCF), said one of the root causes of zoonotic disease outbreaks is the increasing encroachment into natural habitats.

Egbe noted that factors such as habitat destruction, wildlife exploitation, and the loss of key species like vultures are major contributors to the increased risk of zoonotic disease transmission.

“For zoonotic transmission to occur, humans and wildlife must come into contact — something that should rarely happen if wildlife remained in their natural spaces and populations were kept at healthy levels,” Egbe said.

“In Nigeria, we’ve lost over 95 percent of our vulture population. Vultures play a critical role in controlling disease by disposing of animal carcasses. Without them, decaying bodies are left to contaminate water sources and spread pathogens.”

While enforcement efforts like increased border inspections, anti-poaching patrols, and seizures of illegal wildlife products continue. A suggests that without reversing destructive development policies, wildlife protection framework remains fragile.

Mark Ofua, a conservationist, wildlife veterinarian, and spokesperson for Wild Africa, told TheCable that zoonotic diseases are becoming more common than many Nigerians realise.

Ofua noted that while some zoonotic diseases like rabies or tuberculosis have become familiar and treatable, the real danger lies in novel pathogens — diseases that emerge for the first time in humans.

“The real challenge and danger lie in exposure to a zoonotic disease that is novel,” Ofua said.

“The COVID-19 pandemic that occurred around 2019–2020 was a zoonosis. It originated from animals. And because it was a novel zoonosis, you can recall the massive impact it had and how it shook the world.

“Now, imagine if COVID-19 had started in Nigeria or somewhere else in West Africa, it could have wiped out a significant portion of the population before the western world even began to develop a response. That’s exactly what we try to guard against.”

As a wildlife veterinarian, Ofua regularly handles species that carry high-risk pathogens, but he worries that with limited government support, poor infrastructure, and weak public awareness, the risks of zoonotic spillovers remain dangerously high.

He also expressed concern with the manner at which bushmeat traders handle wild animals in unsafe and unhygienic conditions.

Ofua warned that many supposed malaria cases in Nigeria may actually be misdiagnosed zoonotic infections like — a bacterial infection that spread through contact with infected animal urine, which mimics malaria symptoms and respond to the same drugs, delaying accurate diagnosis and public health response.

“Veterinarians are the guardians of human health, standing at the doorway between animal and human disease spillovers. Unfortunately, we’re often under-resourced and overlooked,” the veterinarian added.

On June 21, Akin Abayomi, Lagos commissioner for health, recent data shows that 95 out of every 100 cases of fever in the state are not caused by malaria.

Abayomi warned that self-medication fuels the misuse of antimalarials and antibiotics, which accelerates antimicrobial resistance — a condition where common infections become harder to treat.

Speaking further, Offua noted that zoonotic diseases are a real and present threat, especially as some are “becoming resistant to existing antibiotics”.

He warned that without careful attention, this could lead to outbreaks or pandemics that might be difficult to control.

He called for urgent collaboration between the government, private sector, and the public to prioritise this issue, noting that persistent diseases like Lassa fever continue to challenge Nigeria. He said efforts must be made to prevent new threats from emerging unnoticed.

Ofua added that the government must take stronger action by intensifying public education and enforcing stricter regulations.

“Zoonotic disease education should be part of school curriculums. People don’t know what they’re exposing themselves to,” he noted.

According to Egbe, addressing the booming bushmeat trade issue requires more than just raising awareness.

She said it demands sustainable, community-tailored alternatives developed with local input, as bushmeat remains a crucial source of protein for many rural communities.

“People come into direct contact with blood and saliva when they hunt or handle wildlife,” Egbe added.

“In the absence of proper regulation and awareness, this contact becomes a highway for diseases like Lassa fever and monkeypox.”

As Nigeria joins the rest of the world to mark Zoonoses Day, observed annually on July 6 to raise awareness of the risks of infectious diseases of animal origin, Egbe urges policymakers to focus more on prevention than reaction.

“Once an outbreak occurs, the cost — financially and in human lives — is enormous. That is why enforcing wildlife protection laws, restoring degraded ecosystems, and empowering communities with sustainable alternatives must be part of any national strategy,” she added.

Voices like Ofua and Egbe continue to echo the urgent need for preventive action, sustainable alternatives, and wildlife conservation before the next spillover triggers yet another crisis.

However, for survivors of zoonotic diseases like Olanrewaju, recovery goes beyond physical healing. It means carrying the weight of an illness that nearly took his life, and enduring the stigma that follows.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1285617372-abe7aa8ae9e4436a9a0d12393ff7aa52.jpg)