Hurricane season 2025: Trump's NOAA expects more tropical storms than average | Vox

Hurricane season in the Atlantic has officially begun.

And while this year will likely be less extreme than in 2024 — one of the most destructive seasons ever, with the earliest Category 5 hurricane on record — it’s still shaping up to be a doozy.

Forecasters at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) predict “above-average” activity this season, with six to 10 hurricanes. The season runs from June 1 to November 30.

Chance of an above-normal hurricane season.

Hurricanes expected this season, meaning tropical storms with wind speeds reaching at least 74 mph.

Major hurricanes, or storms with wind speeds reaching 111 mph or higher.

Named storms, referring to tropical systems with wind speeds of at least 39 mph.

NOAA says it will update its forecast in early August.

At least three of those storms will be category 3 or higher, the forecasters project, meaning they will have gusts reaching at least 111 miles per hour. Other reputable forecasts predict a similarly active 2025 season with around nine hurricanes. Last year, there were 11 Atlantic hurricanes, whereas the average for 1991 to 2020 was just over 7, according to hurricane researchers at Colorado State University.

A highly active hurricane season is obviously never a good thing, especially for people living in places like Florida, Louisiana, and, apparently, North Carolina (see: Hurricane Helene, the deadliest inland hurricane on record). Even when government agencies that forecast and respond to severe storms — namely, NOAA and the Federal Emergency Management Agency, or FEMA — are fully staffed and funded, big hurricanes inflict billions of dollars of damage, and they cost lives.

Under the Trump administration, however, these agencies are not well staffed and face steep budget cuts. Hundreds of government employees across these agencies have been fired or left, including those involved in hurricane forecasting. What could go wrong?

The primary reason is that Caribbean waters are unusually warm right now, Brian McNoldy, a hurricane expert at the University of Miami, told Vox. Warm water provides fuel for hurricanes, and waters in and around the Caribbean tend to be where hurricanes form early in the season.

If this sounds familiar, that’s because the Caribbean has been unusually warm for a while now. That was a key reason why the 2024 and 2023 hurricane seasons were so active. Warm ocean water, and its ability to help form and then intensify hurricanes, is one of the clearest signals — and consequences — of climate change. Data indicates that climate change has made current temperatures in parts of the Caribbean and near Florida several (and in some cases 30 to 60) times more likely.

The Atlantic has cooled some since hitting extremely high temperatures over the last two summers, yet “the overall long-term trend is to warm,” said McNoldy, a senior research associate at the Rosenstiel School of Marine, Atmospheric, and Earth Science.

The other key reason why forecasters expect an ample number of hurricanes this year has to do with a complicated climate phenomenon known as the ENSO cycle. ENSO has three phases — El Niño, La Niña, and neutral — that are determined by ocean temperatures and wind patterns. And each phase means something slightly different for hurricane season.

Put simply, El Niño tends to suppress hurricanes because it causes an increase in wind shear — the abrupt changes in wind speed and direction. And wind shear can disrupt hurricanes. In La Niña years, meanwhile, there’s little wind shear, allowing hurricanes to form, and they’re often accompanied by higher sea surface temperatures in the Atlantic.

Right now the ENSO phase is, rather unexcitedly, neutral. That means there won’t be the high, hurricane-blocking wind shear of El Niño, but the conditions won’t be as favorable as they are in La Niña. This all leads to more unpredictability, according to climate scientists.

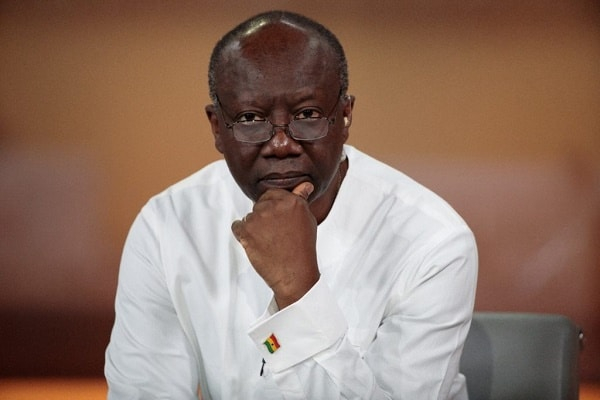

When publishing the NOAA hurricane forecast last month, Commerce Secretary Howard Lutnick, who oversees NOAA, said “we have never been more prepared for hurricane season.”

Climate scientists have challenged that claim.

They point out that, under the Trump administration, hundreds of workers at NOAA have been fired or otherwise pushed out, which threatens the accuracy of weather forecasts that can help save lives. FEMA has also lost employees, denied requests for hurricane relief, and is reportedly ending door-to-door canvassing in disaster regions designed to help survivors access government aid.

“Secretary Lutnick’s claim is the sort of lie that endangers the lives of people living along the Gulf and Atlantic coasts, and even those further inland unable to escape the extensive reach of associated torrential rains and flooding,” Marc Alessi, an atmospheric scientist at the Union of Concerned Scientists, an environmental advocacy group, told Vox. “Notwithstanding the valiant efforts of dedicated career staff, this administration has taken to actively thwarting the vital scientific work at agencies including NOAA that communities rely on to stay safe throughout hurricane season.”

According to Alessi, a handful of National Weather Service offices along the Gulf Coast — which is often hit by hurricanes — currently lack lead meteorologists.

“Missing this sort of expertise in the face of a projected above-average hurricane season could lead to a breakdown in proper warning and evacuation in vulnerable communities should a storm strike, potentially leading to more deaths that could have otherwise been avoided,” Alessi said.

As my colleague Umair Irfan has reported, the National Weather Service is also launching weather balloons less frequently, due to staffing cuts. Those balloons measure temperature, humidity, and windspeed, providing data that feeds into forecasts.

“They’ve been short-staffed for a long time, but the recent spate of people retiring or being let go have led some stations now to the point where they do not have enough folks to go out and launch those balloons,” Pamela Knox, an agricultural climatologist at the University of Georgia extension and director of the UGA weather network, told Irfan in May. “We’re becoming more blind because we are not having access to that data anymore. A bigger issue is when you have extreme events, because extreme events have a tendency to happen very quickly. You have to have real-time data.”

The White House is also trying to dramatically shrink NOAA’s funding, proposing a budget cut of roughly $2 billion. In response to the proposed cuts, five former directors of the National Weather Service signed an open letter that raises alarm about what funding and staffing losses mean for all Americans.

“Our worst nightmare is that weather forecast offices will be so understaffed that there will be needless loss of life,” the former directors wrote in the letter. “We know that’s a nightmare shared by those on the forecasting front lines — and by the people who depend on their efforts.”