Healthcare in Crisis: Long waits, overworked doctors as medical professionals flee

Josephine Awode’s 15-year-old son began panting and wheezing. With each breath, his chest expanded and contracted visibly underneath his t-shirt.

It was an asthma crisis. Awode reached for her son’s ferinol tablets. He used the medication, but the wheezing did not stop. Awode hopped into a commercial tricycle and rushed her son to a government-owned hospital in Ijebu-Ode and proceeded to the emergency ward.

The nurses checked his vitals, ran tests on him, and asked Awode and her son to wait to be attended to. There was a long queue waiting to be attended to.

“They told us to wait, and we would go in according to how we came. Unfortunately, if one patient goes in, it would take them more than one hour to call another patient in. I felt like crying. I was so furious,” she recounted.

Frantically, she barged into a doctor’s office to find out what the delay was about. However, the doctors told her that if she could not exercise patience, she should go to a private hospital to seek medical attention for her son.

This was after waiting at the hospital for eight hours to be attended to.

“We got to the hospital around 9 am and left the hospital past 5 in the evening. We spent 8 hours waiting at the hospital.

Awode’s experience mirrors the harsh reality of many Nigerians seeking medical attention in government hospitals — long wait hours and frustration.

Why Nigerians spend long waiting hours at hospitals

With one doctor attending to 10,000 patients, Nigeria has one of the lowest doctor-patient ratios in the world. A figure far below the World Health Organisation (WHO)’s benchmark of one doctor for every 600 patients.

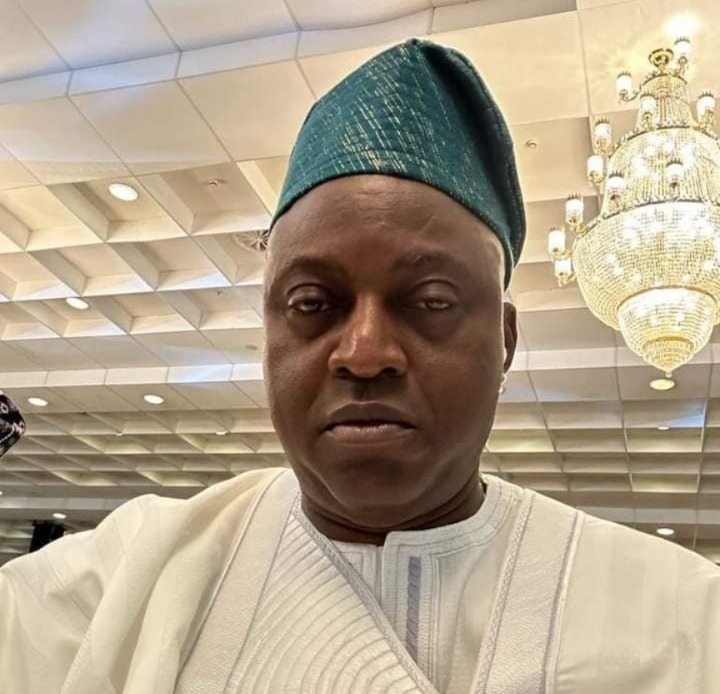

According to the President of the Nigerian Medical Association (NMA), Prof. Bala Audu, the ratio is approximately 1000% below the WHO’s recommendations.

Audu attributed the low patient-doctor ratio to the mass migration of Nigerian healthcare workers abroad.

“The doctor-patient ratio is about 1,000% less than what the WHO recommended. This deficit is primarily driven by the brain drain of healthcare workers, commonly referred to as the ‘Japa Syndrome,’” he said.

Nearly 19,000 Nigerian doctors have migrated in the past seven years. The migrating doctors are motivated by the search for greener pastures, leaving behind a healthcare system they have deemed unfavourable.

For many years, Nigerian doctors under the umbrella of various healthcare professional associations have protested low pay, unpaid salaries, poor welfare packages, and have embarked on industrial actions.

As more doctors emigrate, many Nigerians, like Awode, bear the brunt of a healthcare system with thinning medical professionals.

A frustrating search for specialists

In May, Awode and her siblings were seeking medical attention for their brother, who was diagnosed with hepatitis.

The Ogun State resident told The Guardian that she took her brother to a private hospital, but he was later referred to the Ogun State University Teaching Hospital (OSUTH).

On getting to OSUTH, Awode was informed there was no specialist available to attend to him.

“They told us there was no specialist available and they could not attend to him. The nurses were advising us to take him to Babcock Specialist Hospital for prompt attention. We eventually took him to the Federal Medical Centre (FMC) in Abeokuta.”

A public relations specialist who resides in Lagos State, Omolewa Adeoye, narrated a similar experience to The Guardian.

Adeoye, who has a neurological condition, recently had a health scare which led her to the Lagos State University Teaching Hospital (LASUTH). The public relations specialist, who frequents private hospitals, said her experience at LASUTH was an eye-opener as it made her realise how difficult it is for average Nigerians to access proper medical care, especially when they are in dire need.

That day, Adeoye left her home in the Ikeja axis of Lagos for LASUTH around 6 am. She told The Guardian that she was asked to wait almost two hours for the doctors to start attending to patients. She also waited an extra seven hours before it got to her turn.

While describing the sight she met at the hospital, Adeoye said the waiting area was packed with many patients and there was only one consultant available to attend to over 30 patients, some of whom had been coming back for days without any luck.

“I waited several hours. What made it worse was seeing people slip money to nurses to get their hospital files pushed up to the pile of files. It felt unfair,” she lamented.

“You are sitting there sick, tired, and anxious and you realise it is not just about arriving there early, but who you can pay more. It was heartbreaking to watch sick people, some elderly people, just sitting and waiting, hour after hour.

“I was emotionally drained. The fear of not knowing what was wrong with me, combined with the endless waiting, made it one of the most difficult days I have had.”

Adeoye was eventually attended to, but she said the experience left her shaken and realised that even when help is available, it can feel painfully out of reach.

“Finding a specialist in this country, especially a neurologist or endocrinologist, can feel like a full-time job. Either the few available ones are overbooked, or they are in another state and when you do find one, you either have to wait weeks for an appointment or pay through the nose at a private hospital,” she added.

The mass migration of doctors from Nigeria has left behind a trail of stress and burnout for those who remain. With many of their colleagues seeking better opportunities abroad, the workload for the remaining doctors, who are forced to bear the burden of caring for a large patient population, has increased significantly.

According to a report published in 2024, the former chairman of the NMA in Kwara State, Ola Ahmed, revealed that the state has only 650 doctors attending to the state’s 3.6 million population.

Babatunde (not real name), a doctor in the University of Ilorin Teaching Hospital (UITH), told The Guardian that the hospital loses at least one doctor to migration almost every month, adding that the hospital, which used to have about 600 medical professionals over the years, has now reduced to about 400.

According to him, this has put a strain on the doctors left behind and has increased the number of times they are on call, with doctors working about 15 call duties in a week, as opposed to the eight call duties outlined in their terms of agreement.

“The migration has been happening over time, and because of that, the workload has changed. We are expected to do two call duties in a week. Call duties mean apart from your regular 8 am to 4 pm shift, you stay beyond your closing time to attend to patients.

“Instead of two in a week, most departments are running alternative day calls. That means in a month, instead of two in a week, you are doing 15,” Babatunde told The Guardian.

He added that the junior doctors bear the brunt of the workload most times. The doctor said that the work has become mentally and physically taxing as doctors experience burnout and medical conditions as a result.

“One of my seniors had immunosuppression as a result of the stress and had shingles. Shingles is a condition that happens when the chickenpox virus is reactivated in the system of someone who once had chickenpox. It only gets to be reactivated when someone is immunosuppressed.”

Babatunde also attributed the increased workload to the low number of new recruits.

“The workload is not just terrible because people have left, it is because people are not there. My department needed four doctors but I was the only one who applied. Another time, they put out an advert and only one person applied again. People are not even applying. So, how do you even want to get new people?” he added.

In April, the Kwara State Government lamented the need to recruit more medical doctors in the state. The Executive Secretary, Kwara State Hospital Management Board, Dr AbdulRaheem AbdulMalik, said the state government had only 89 doctors on its payroll, instead of about 200 that were needed.

In an interview with The Guardian, an Ogun State-based surgeon who pleaded anonymity also said that some of her colleagues have migrated in search of greener pastures, and the hospital lacks an adequate number of surgeons required for seamless healthcare delivery.

Speaking on the impacts of the migration on her and the other colleagues left behind, she said the workload has increased for them.

“I attend to roughly 180 patients monthly. There are times that we are forced to reschedule cases because we can’t attend to everyone,” she said.

While lamenting the working conditions the doctors left behind are forced to work in, Babatunde said they are not compensated well enough for the extra workload they now have to shoulder, adding that doctors have many responsibilities and relatives perceive them as wealthy people.

“You work around the clock and don’t have time to bond with your family. Relatives plead for your assistance and you can’t chase them away because they are your kith and kin.

“You don’t have money to spend and can’t even afford to go for vacations when you are less busy or on leave to de-stress. You are still within this, permit me to say, insane country.

“Like my colleague would say, a doctor is one sickness away from poverty. God forbid if anyone gets to have a serious health condition. It can drain all that you have saved in the past year because healthcare is getting really expensive.”

He added that he has considered migrating like many of his colleagues, but is not actively working towards it.

The Ogun-based surgeon shared similar thoughts.

“I have considered seeking greener pastures but I have stayed back because of my family and aged parents,” the surgeon said.

As the workload increases and burnout intensifies, the government offers doctors no support. To fill this void, doctors like Babatunde turn to family and friends for mental and emotional support.

“There is no support system anywhere. If there is anyone anywhere perhaps, it is the one that you as a doctor develop for yourself and the primary one is your family.

In 2023, the National Assembly introduced a bill to curb the mass migration of doctors. The bill, called “A Bill for an Act to amend the Medical and Dental Practitioners Act, Cap. M379, Laws of the Federation of Nigeria, 2004,” sought to mandate any Nigeria-trained medical or dental practitioner to practise in Nigeria for a minimum of five years before being granted a full licence by the council.

It was, however, objected to by the Nigerian Association of Resident Doctors (NARD), which vowed that it would resist any attempt to enslave Nigerian medical doctors under any guise. The Federal Government kicked against it.

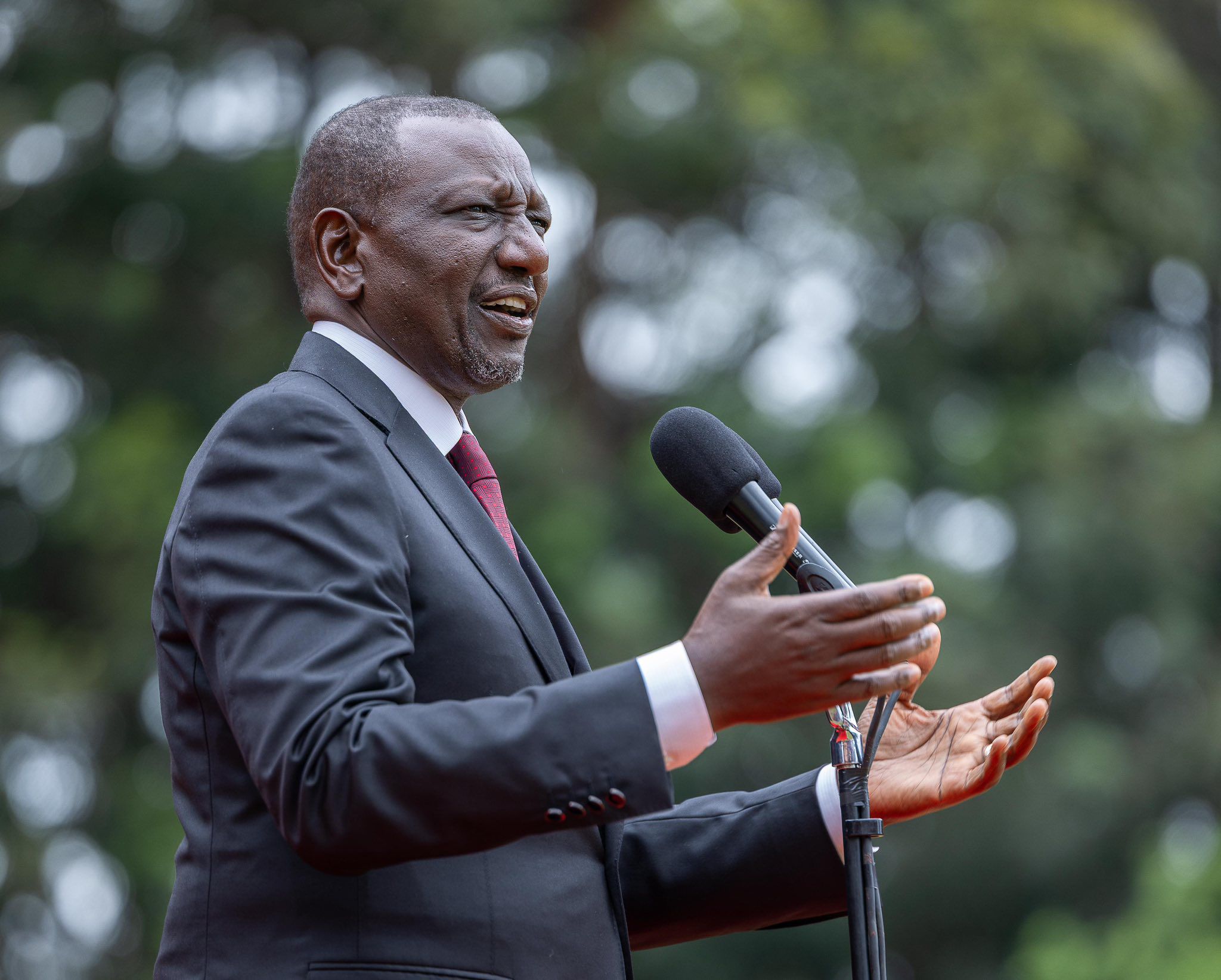

Nigeria’s President Bola Ahmed Tinubu, in 2024, approved the National Policy on Health Workforce Migration to address the continued exodus of Nigerian doctors abroad. The policy aimed to woo an estimated 12,400 Nigerian-trained doctors practising abroad.

While Nigeria’s health sector grapples with this mass migration among other challenges, Tinubu recently signed an agreement with Saint Lucia to send Nigerian doctors to the Caribbean country.

The NMA slammed the President for this move, describing it as morally unjustifiable.

“We consider this move a deeply troubling contradiction and an attempt to bolster Nigeria’s international image while failing to meet the basic obligations owed to doctors at home who are toiling hard to serve Nigeria,” the NMA noted in a circular.

To curb the mass migration of doctors, Babatunde implored the government to provide better wages for doctors, improve healthcare facilities, improve security, and address the issue of kidnapping and assaults on doctors.

“Doctors get kidnapped and are beaten up inside the hospitals. How do we expect them to stay when they experience violence in hospitals? Make doctors do the work of doctors. We should only be worried about caring for patients; we should not be worried about the unavailability of medicine in the pharmacy. We should not be worried about poor electricity in the hospital. We should not be worried about the water that we use to scrub when he wants to do surgery, the bed space, and where we will put our patients.”

While other doctors are working towards achieving their migration plans, Babatunde, who has considered migrating like them, said he has remained behind because of a sense of responsibility and a divine calling.

“Some of my colleagues are in the process, and it is only a matter of time before they leave because they are already doing the exams and qualifications required to leave.

The reason I am still here is because of a sense of responsibility and because God wants me to stay. Even though there may be challenges here, it is just a matter of time; God will work things out for us. If all of us leave, who will take care of the people we are leaving behind?” Babatunde asked.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/GettyImages-1285617372-abe7aa8ae9e4436a9a0d12393ff7aa52.jpg)