Health trends in the ASEAN region | Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation

: Welcome to Global Health Insights, a podcast from IHME, the Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation. I’m Rhonda Stewart.

In this episode, we’ll hear from IHME Affiliate Associate Professor Marie Ng as she discusses a series that’s the first of its kind focused on health in the ASEAN region, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations. The 10 countries in the region are Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam.

The region is the world’s fifth largest economy and one of the fastest developing regions in the world. ASEAN has a population of 676 million, which is one and a half times larger than that of the European Union and comprises almost 9% of the world’s population.

The 10 countries in the ASEAN region face a range of health challenges. The new series of studies published in The Lancet focuses on four of those: mental disorders, cardiovascular diseases, smoking, and injuries.

In the ASEAN region, more than 80 million people suffer from mental disorders, which is a 70% increase since 1990. 37 million people in the region suffer from cardiovascular disease and 1.7 million die from it, making it one of the fastest growing non-communicable diseases and the leading cause of death. The number of smokers has increased in every ASEAN country and by 63% to 137 million regionally, which is 12% of the total number of global smokers. Some 35 million people across the region are injured every year from various kinds of accidents and incidents, and road injuries is the top cause of death in this category, making it a public health priority.

Given ASEAN’s aging population and rapid economic growth, understanding these trends and their policy implications is essential to improve health and well-being in the region and globally.

Welcome, Marie, and thanks so much for being on the podcast.

So the countries that make up the ASEAN region are Brunei, Cambodia, Indonesia, Laos, Malaysia, Myanmar, the Philippines, Singapore, Thailand, and Vietnam. What makes it useful to study health in these countries as a group?

: Yeah, the Association of Southeast Asian Nations, which is also known as ASEAN, is a geopolitical network that was established in 1967 in the wake of Cold War to promote peace and socioeconomic cooperation among countries in the region. ASEAN is home to 676 million people, a population size that is one and a half times larger than that of the European Union.

Studying health in these countries as a group is helpful for several reasons. At a local level, it helps propel the public health agenda and inform policy transformation. And at a regional level, there is a lot the 10 member states can do together to improve the health of their citizens.

And globally, the socioeconomic characteristics of these regions are extremely diverse, ranging from low-middle-income countries such as Laos and Myanmar to high-income countries such as Brunei and Singapore. It has been noted before that ASEAN is a microcosm of global health. The epidemiological landscape reflects the breadth and heterogeneity we see worldwide. So what we can learn here can potentially have implications for other countries around the world.

: There are four papers in the series. They cover mental health disorders, cardiovascular diseases, smoking, and injuries. Why did you and the team focus on these four conditions?

: We chose these four topics to highlight some of the ongoing and emerging population health challenges faced by the region in recent years. Especially with COVID-19 pandemic, there has been quite a lot of discussion on infectious disease and pandemic emergency preparedness. However, there are other important health priorities that we believe the region could focus on. Further, cardiovascular disease is the leading cause of disease burden and death in all ASEAN countries. So our hope is to provide an overview of the current situation and offer insights into potential areas for policy intervention.

Mental disorders is a topic less explored in this region. There is a lot of stigma around mental health in many countries. Although things have begun to improve in recent years, we hope that our study on mental health and mental disorders can further raise awareness of the important issue.

Smoking has long been a significant problem in this region and is a leading risk factor for many non-communicable diseases. ASEAN accounts for 12% of the global smoking population, and tobacco production is a major industry in some member states. So it is important to track progress on this issue.

And finally, injury has been a concern in this region. In particular, road injuries have been a longstanding public health issue in several countries. The goal of the injury paper is to assess how countries have performed in the last 30 years and also to broaden the scope of injury so it’s not just about road injuries, but also to raise awareness regarding falls, self-harm, and other types of injury causes.

: Okay, great. And let’s start with the study on mental disorders. How did these rank in terms of disease burden across the region? Were there specific disorders that were most prevalent?

: Yeah, mental disorders have become one of the top 10 causes of disease burden in all ASEAN countries except Myanmar, where it ranked the 11th. This means that relative to other causes of disease, mental disorders are increasingly contributing to health loss among the ASEAN population.

We observe some association in the disease burden and mental health issues with respect to economic development. For example, mental disorders are ranked fourth in Singapore and Malaysia and ranked fifth in Brunei and Singapore. Malaysia and Brunei are the high-income and upper-middle-income countries in this region.

And the burden of mental disorders is higher and similar to global trend. In terms of the specific disorder that was more prevalent, anxiety disorder and depression are the most common, with higher rates observed in women than men.

: And the team found that more than 80 million people suffer from one of the 10 disorders studied, which is a 70% increase since 1990. What’s driving that increase? You did also refer to the impact of stigma when it comes to discussing mental disorders, right?

: One of the major drivers of the increase is demographic changes. The age-standardized prevalence of mental disorders has only increased by 6.5% since 1990. But as you noted, the number of people experiencing mental disorders has increased by 70%. So the contrast between prevalence and number is quite big. And this is partly due to an aging population. The number of individuals over the age of 70 with mental disorders actually has increased by 182% in the past 30 years.

And beyond these demographic changes, there are different types of stressors that are increasing the risk of mental disorders. Some of them are more commonly discussed, for example the influence of social media. But then within the ASEAN region, there are also other social environmental issues that many people are facing, including poverty, low education attainment, food insecurity, natural disasters – for example, the recent earthquake in Myanmar – and also climate events. These factors all increase the vulnerability to poor mental well-being.

: Wow, those numbers are really striking. And in terms of demographics, who’s most impacted by mental disorders in the region?

: Yeah, the demographics of mental disorders in ASEAN resemble the global trends in terms of prevalence. Mental disorders begin to increase around the age of 10 and continue to peak into mid-adulthood. And females tend to have a higher prevalence than males. However, when we are considering the relative disease burden, that is comparing mental disorders with other diseases, the age group that experiences the highest burden is between the ages of 10 to 14 years old.

In countries such as Singapore, over a quarter of disease burden in the age group is caused by mental disorders. In other words, for those age 10 to 14, mental disorders are a key cause of health loss.

: Okay, so this is really something that’s seen quite commonly among young people, among males and females as well. So that’s really interesting to note.

Let’s talk about cardiovascular disease, which is the leading cause of mortality and morbidity in the region. Looking at the period of 1990 to 2021, it’s important to distinguish between the increase in the number of cases in ASEAN, which has gone up by 148%, and the increase in prevalence, which is just 3% – but that 3% increase regionally translates to 10% of the global burden of cardiovascular disease. Explain to us why it’s important to look at the numbers here and not just prevalence.

: Prevalence shows the proportion of people within the population experiencing a disease. So if prevalence is stable, it typically suggests that the spread of disease is under control. However, the number of cases reflects the actual number of people experiencing the condition, which has implications for resource allocation.

Although the proportion of people affected may be small, the actual number can be quite big. So for example, in 1990, we observed that 8% of individuals aged 50 to 54 in ASEAN experienced cardiovascular disease.

The prevalence in 2021 is actually similar. It’s also 8% in terms of cardiovascular disease prevalence among individuals aged 50 to 54. So there’s almost no change in the prevalence for this particular age group. However, if we look at the number of individuals in this age group affected by cardiovascular disease, it actually doubled. It changed from 1.3 million in 1990 to 3.2 million in 2021. The actual number here reflects the true health care service demands that need to be addressed.

: And which cardiovascular diseases had the highest rates of prevalence in the region?

: The top three cardiovascular diseases that have the highest prevalence in the region are first, ischemic heart disease, second, stroke, and third, lower extremity peripheral arterial disease. And this pattern is actually consistent with the global trends and what factors contributed to the rise in these diseases.

The largest contributors to cardiovascular diseases in ASEAN include high systolic blood pressure, which accounts for more than 50% of the disease burden. Then it’s followed by dietary risks such as high sodium consumption, low fruit consumption, and low whole grain intake. The third risk factor is actually air pollution, followed by tobacco use, high cholesterol, and then high body mass index, which essentially is referring to obesity and overweight.

Over the past 30 years, we have observed some improvement in the control of certain risk factors. Especially air pollution is one that we are observing a substantial decline in what we call the attributable fraction. That means air pollution is contributing to less of the cardiovascular disease burden. However, two factors that are steadily increasing are overweight and obesity as well as high fasting plasma glucose, basically referring to high blood sugar.

: And were there any country-specific findings that stood out with cardiovascular disease?

: This reflects disparity in access to lifesaving interventions. For example, implantable devices are not readily available in many parts of the region. And cath lab access is very limited as well. Specialists are lacking. The density of cardiothoracic surgeons is below 0.01 surgeon per 100,000 population in Cambodia and Myanmar, which means that for every 100,000 people, there’s less than one surgeon serving the population. There’s a need to scale health care service capacity and ensure universal access to these lifesaving interventions.

: And so, in addition to scaling up health service capacity, as you mentioned, what are some effective strategies to improve access to cardiovascular treatments in underserved regions?

: Now, first, there is a need for infrastructural investment, specifically investment in hospitals, surgical theaters, and relevant equipment to establish the physical space or physical needs to conduct these critical care interventions.

Now second, there is a need for workforce training. As noted, there is a significant shortage of specialists in this region. There’s actually a multilateral collaboration set up in ASEAN in 2009 which is called the Mutual Recognition Arrangement on Medical Practitioners, which aims to enhance mobility and capacity building and information exchange.

This agreement can actually be further leveraged to strengthen specialized health care workforce, and it would be beneficial to see this arrangement utilized more effectively to increase workforce capacity.

And third, financial coverage is essential to enable access. In many countries, advanced interventions are predominantly provided in private institutions. There’s a need for better public-private coordination to ensure equitable access to these treatments, as well as provision of financial support for the underserved population to avoid catastrophic health expenses.

And finally, while there’s a lot of discussion focusing on access to treatment, it is important to emphasize that the most cost-effective approach to reducing the burden of cardiovascular disease is actually prevention. Tobacco control, prevention and management of overweight and obesity, effective management of blood pressure, cholesterol, and blood glucose can be low-cost and effective strategies for preventing cardiovascular diseases.

: That’s fascinating stuff. And let’s move on and talk about smoking. What were some of the key findings there?

: Smoking prevalence in the region is still very high, especially among men. There’s an estimated 48.4% smoking prevalence among men in 2021. In Indonesia, smoking prevalence is as high as 58%, and in Vietnam it’s estimated to be 47%, although prevalence itself has decreased by 12% compared to 1990. But the total number of smokers has actually increased by 63%.

So there’s an estimated 137 million smokers in ASEAN in 2021. This is a very alarming number, and there has been no significant reduction in smoking prevalence among those between 10 to 14 years old. In ASEAN, the prevalence of youth smoking in the age group was estimated at 11% among males. At the regional level, however, in Malaysia, for example, the smoking prevalence among boys age 10 to 14 is as high as 20%. In Myanmar and Philippines and Thailand, Indonesia, the rate is all about 10%. This situation is quite concerning.

: Absolutely. Just tell us a bit more about the findings by age and gender.

: Sure, smoking prevalence among youth has not changed much, as I mentioned, in the past 30 years. And the prevalence is at 11% for that age group and as high as 20% in Malaysia, with many countries also above 10%. And as noted earlier, males in general have a much higher smoking preference than females. Smoking prevalence among men in ASEAN is estimated at 48% at the regional level, while the smoking prevalence among females is actually only 4.4%, much lower.

However, there are some variations. In Myanmar and Philippines, female smoking prevalence is roughly around 8%, which is twice the regional average. It is interesting to note that in Singapore, smoking prevalence among males is the lowest in the region, measured at only 20%. But female smoking prevalence in Singapore actually ranks fourth in the region.

: And how do the numbers that you found for smoking in the ASEAN region compare to global figures on smoking?

: The number of smokers In ASEAN constitutes 12% of the global smoking population, even though the total population of ASEAN is only 8% of the global population. So this suggests that ASEAN contributes a disproportionate number of smokers. And in terms of death, there were over half a million deaths attributable to smoking in 2021, which is roughly 8% of the global deaths attributable to smoking.

Okay, so clearly there is still more to be done to address smoking in the region. And let’s talk about the final paper in the series, on injuries. What are some of the most common types of injuries found in the region?

: The top causes of injuries in ASEAN are road injuries, falls, self-harm, drowning, and interpersonal violence. Road injuries are the leading cause of injury burden in all ASEAN countries except Philippines and Singapore. In the Philippines, the number one cause of injury burden is interpersonal violence, while in Singapore the leading cause of injury is falls.

In 2021, there were an estimated 120,000 deaths resulting from road injuries. Falls resulted in approximately 56,000 deaths in the region, whereas self-harm and drowning each resulted in about 30,000 deaths in the region.

: And which findings stood out in terms of age and gender?

: There are some fairly consistent age patterns in terms of the types of injuries affecting the different age groups. Below the age of 9, drowning is the most common cause of injury-related burden. Road injury burden is the highest among 15 to 19 age group. In Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and Vietnam, around the age of 20 to 24, there’s a rise in the burden of self-harm, and as people age, the burden of falls gradually increases. And in general, the burden of injuries is higher among males than females.

: And what stood out to you in terms of findings at the country level?

: We observed the highest road injury mortality rate in Thailand and Malaysia. In Thailand, the age-standardized mortality rate associated with road injuries was estimated at 30 per 100,000. In Malaysia it is estimated at 24 per 100,000. Both of these numbers are much higher than the global average, which is 15 per 100,000. And in Thailand, the most common type of road injury is motorcycle accidents. In contrast, in Malaysia it is actually motor vehicle accidents.

Falls are a growing issue in many countries, although the overall prevalence of falls has been declining – but the absolute number has not, and falls now result in the highest disease burden. In countries such as Singapore, self-harm is also a substantial issue in several countries. It is one of the top three causes of injury disease burden in Thailand, Malaysia, Singapore, and Brunei. While the incidence of self-harm tends to be higher among females, the actual disease burden or deaths are higher among males.

And finally, drowning. Drowning among young children is an important issue in Thailand, Cambodia, and Myanmar. In Thailand, drowning constitutes 12% of the disease burden among children between the ages of 5 to 9.

: Wow. Marie, what’s the main thing that people should take away from this comprehensive study of the ASEAN region?

: We have discussed quite a bit about the current disease burden, epidemiological landscape of various conditions, and trying to bring attention to the topics that have high disparity, for example in cardiovascular disease mortality, high smoking prevalence, the growing number of mental disorders, and the persistent burden of road injuries in certain countries. I do want to note that despite these challenges, the region has made remarkable progress. If you do look through the time trend in many areas, prevalence and mortality rates are declining, indicating improvement in health care and also broader socioeconomic factors.

One thing I do want to highlight is that there are quite a bit of challenges in our analysis, one of which is data sparsity. Many countries in this region are still in the early stage of establishing comprehensive health information systems, and health data are not readily available for mental disorders. This is a topic that has not been well studied: research is sparse, and regular surveillance and monitoring are not common. The same applies to injury. Data on self-harm are rarely recorded properly. As the region continues to advance socially and economically, I would urge for further investment in strengthening health monitoring and surveillance systems and to build the evidence base that is essential for assessing existing programs and for informing future policy transformation.

: And speaking of policy, let’s talk about some of those implications. You mentioned the need to invest in strengthening health monitoring surveillance systems, also expanding health services throughout the region. How can policymakers and other decision-makers use these findings?

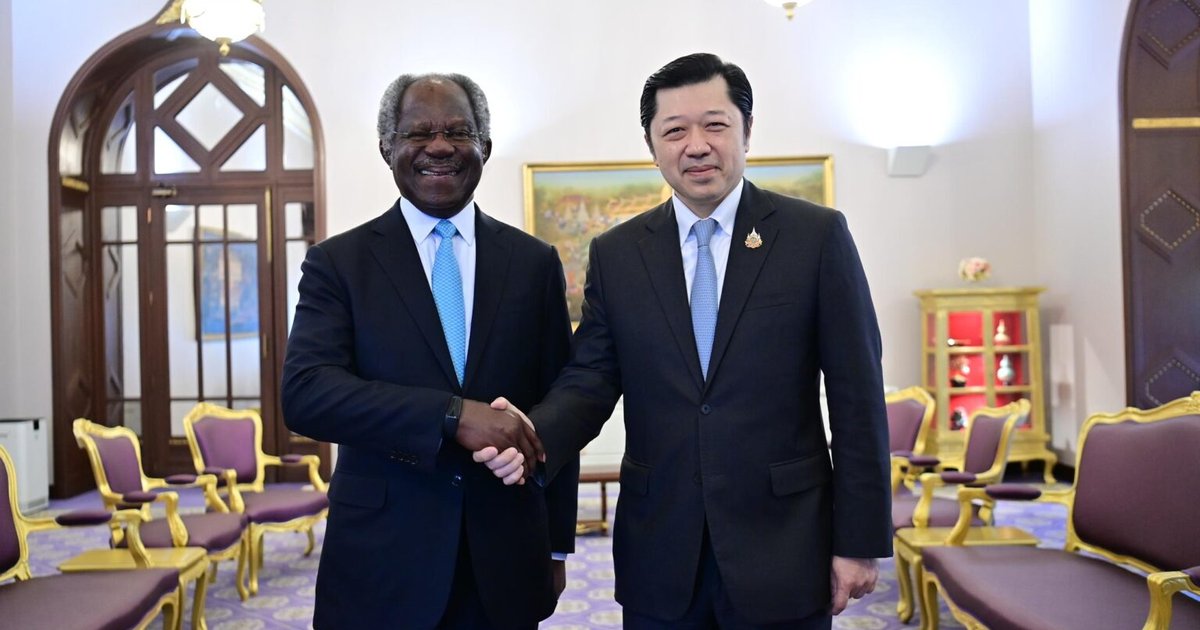

: Yeah, as the ASEAN health sector is going to meet late June for the 19th ASEAN Senior Officials Meeting on Health Development and to discuss the Post-2025 agenda, this is a great opportunity where our evidence can be leveraged, especially to consider how this can be used in reprioritizing resources.

I’ll also encourage senior officials and minister and stakeholders to think about how to use the Multilateral Public Health Framework initiative that was developed in the wake of COVID-19 to foster multilateral collaboration. Some of the framework that was developed during the COVID period includes the ASEAN Public Health Emergency Coordination System, the Risk Assessment and Risk Communication Center, and also Drug Security and Self-Reliance framework. I believe that a similar collaborative framework can play a role not only in infectious disease, but also for tackling the rising cardiovascular disease and other non-communicable disease burden, which actually causes more deaths than COVID-19 – and some of our evidence here can serve the purpose.

In the upcoming discussion I do want to reemphasize the importance of accumulating data for continuous monitoring and also for policy evaluation. Data are crucial also for negotiation between the Ministry of Health and Ministry of Finance to secure resources and also create policy that balances economic development and public health. So beyond individual countries’ efforts, there’s a lot the region can do together to achieve, and our hope is that these data will serve as a starting point for discussion.

: Great. Well Marie, thank you so much for taking time to tell us about this fascinating and important study.

: Thank you, Rhonda.

: Details about the ASEAN studies can be found at healthdata.org.