From Seattle to Atlanta, new social housing programs seek to make homes permanently affordable for a range of incomes

Seattle astounded housing advocates around the country in February 2025, when roughly two-thirds of voters approved a ballot initiative proposing a new 5% payroll tax on salaries in excess of US$1 million.

The expected revenue – estimated to amount to $52 million dollars annually – would go toward funding a public development authority named Seattle Social Housing, which would then build and maintain permanently affordable homes.

The city has experienced record high rents and home prices over the past two decades, attributed in part to the high incomes and relatively low taxes paid by tech firms like Amazon. Prior attempts to make these companies do their part to keep the city affordable have had mixed results.

So despite nationwide, bipartisan skepticism of government and tax increases, Seattle’s voters showed that in light of a severe affordability crisis, a new role for the public sector and a new, dedicated fiscal revenue stream for housing were not only necessary, but possible.

As a trained architect and urban historian, I study how capitalist societies have embraced – or rejected – housing that’s permanently shielded from market forces and what that means for architecture and urban design.

To me, Seattle’s social housing initiative shows that the country’s traditional, “either-or” housing model – of unregulated, market-rate housing versus tightly regulated, income-restricted affordable housing – has reached its limits.

Social housing promises a different path forward.

After World War I, amid a similarly dire housing crisis, journalist Catherine Bauer traveled to Europe and learned about the continent’s social housing programs.

She publicized her findings in the 1934 book “Modern Housing,” in which she advocated for housing that would be permanently shielded from the private real estate market. High-quality design was central to her argument. (The book was reissued in 2020, reflecting a renewed hunger for her ideas.)

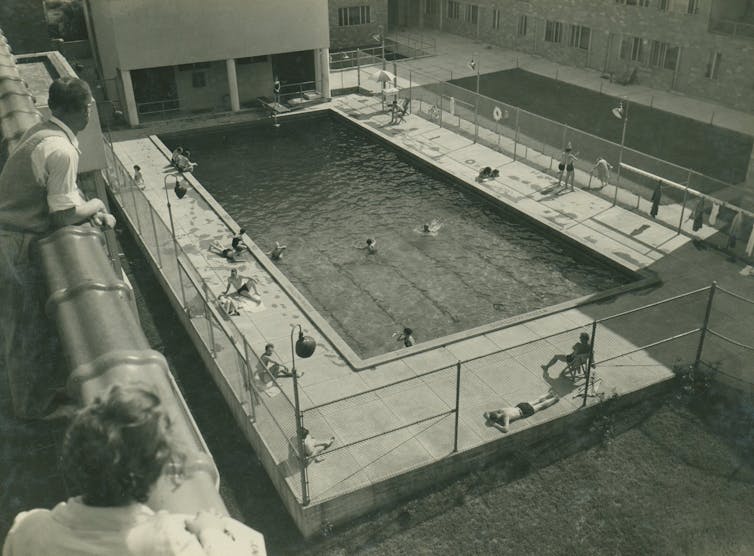

Early New Deal programs supported “limited-dividend,” or nonprofit, housing sponsored by civic organizations such as labor unions. The Carl Mackley Houses in Philadelphia exemplified this approach: The government provided low-interest loans to the American Federation of Full-Fashioned Hosiery Workers, which then constructed housing for its workers with rents set at affordable rates. The complex was built with community rooms and a swimming pool for its residents.

However, the 1937 U.S. Housing Act omitted this form of middle-income housing. Instead, the federal government chose to support public rental housing for low-income Americans and private homeownership, with little in between.

Historian Gail Radford has aptly termed this a “two-tiered system,” and it was problematic from the start.

Funding for public housing in the U.S. – as well as for its successor, private-sector-built affordable housing – has always been capped in ways that fall far short of demand, with access to the homes largely restricted to households with the lowest incomes. Private-sector-built affordable housing depends on dangling tax credits for private investors, and rent restrictions can expire.

While the U.S. promoted this two-tiered system, cities like Vienna pursued a different path.

In Austria’s culturally vibrant capital, today half of all dwellings are permanently removed from the private market. Roughly 80% of households qualify to live in them. The buildings take a range of forms, are located in all neighborhoods, and are built and operated as rental or cooperative housing either by the city or by nonprofit developers.

Rents do not rise and fall according to household income, but are instead set to cover capital and operation expenses. These are kept low thanks to long-term, low-interest loans. These loans are funded through a nationwide 1% payroll tax, split evenly between employers and employees. Renters also make a down payment, priced in relation to the size and age of the apartment, which keeps monthly rents down. To guarantee access to low-cost land, the municipality has pursued an active land acquisition policy since the 1980s.

The inequities created by the two-tiered system – along with the absence of viable options for moderate- and middle-income households – are what social housing advocates in the U.S. are trying to address today.

In 2018, the think tank People’s Policy Project published what was likely the first 21st-century report advocating for social housing in the U.S., citing Vienna as a model.

Across the U.S., social housing is being used to describe a range of programs, from limited equity cooperatives and community land trusts to public housing.

They all share a few underlying principles, however.

First and foremost, social housing calls for permanently shielding homes from the private real estate market, often referred to as “permanent affordability.” This usually means public investment in housing and public ownership of it. Second, unlike the ways in which public housing has traditionally operated in the U.S., most social housing programs aim to serve households across a broader range of incomes. The goal is to create housing that is both financially sustainable and appealing to broad swaths of the electorate. Third, social housing aspires to give residents more control over the governance of their homes.

Social housing doesn’t all look the same. But thoughtful design is key to its success. It’s built to be owned and operated in the long-term, not for short-term financial gain. Construction quality matters, and developers realize it needs to be appealing to a range of tenants with different needs.

In recent years, there have been significant wins for the social housing movement at the state and local levels.

In 2023, Atlanta created a new quasi-public entity to co-develop mixed-income housing on city-owned land. In 2024, Rhode Island voters and the Massachusetts legislature funded pilot projects to test public investment in social housing. And 2025 has seen the the passage of Chicago’s Green Social Housing ordinance.

Many of these programs were directly inspired by affordable housing initiatives in Montgomery County, Maryland.

Since 2021, the county’s housing authority has used a $100 million housing fund to invest in new mixed-income developments. Through these investments, the county retains co-ownership and has been able to bring down the cost of development enough to offer 30% of homes at significantly below market rents, in perpetuity. If Vienna is the global paragon for social housing, Montgomery County has become its domestic counterpart.

In Seattle, social housing will mean homes delivered and permanently owned by Seattle Social Housing, which is funded through the payroll tax on high incomes. The initiative envisions developments featuring a range of apartment sizes to meet the needs of different family sizes, built to high energy-efficiency standards. Homes will be available to households earning up to 120% of area median income, with residents paying no more than 30% of their income on rent. In Seattle, that means that a single-person household making up to $120,000 will qualify.

Despite these successes, many Americans remain skeptical of social housing.

Sign up for a webinar on the topic, and you’ll hear participants question the term itself. Isn’t it far too “socialist” to be broadly adopted in the U.S.? And isn’t this just “old wine in new bottles”?

Join a housing task force, and established nonprofits will be the ones to push back, arguing that they already know how to build and manage housing, and that all they need is money.

Some housing activists also question whether using scarce public dollars to pay for mixed-income housing will yet again shortchange those who most need governmental assistance – namely, the poor. Others point to the need to provide more ways to build intergenerational wealth, especially for racial minorities, who have historically faced barriers to homeownership.

Urban planner Jonathan Tarleton has highlighted another important issue: the danger of social housing reverting over time to private ownership, as has been the case with some cooperatives in New York City. Tarleton stresses the need for “social maintenance” – the importance of telling and retelling the story of whom social housing is meant to serve.

These debates raise important questions. Social housing may be a confusing term and an aspirational concept. But it is here to stay: It has galvanized organizers and policymakers around a new approach to the design, development and maintenance of housing.

Social housing keeps prices down through long-term public investment, ensuring that future generations will still benefit. Developers can design and provide homes that respond to how people want to live. And in an increasingly polarized country, social housing will allow people of various backgrounds, incomes and ideological persuasions to live together again, rather than apart.

Whether it’s the kind found in Seattle, in Maryland or somewhere in between, I believe social housing is needed more than ever before to address the country’s twin problems of affordability and a lack of political imagination.

This article is part of a series centered on envisioning ways to deal with the housing crisis.

_1751880097.jpeg)