France and Africa adjust to new relationships

Franco-African relations have long been framed from the French perspective. However, as new nationalist sentiments sweep Francophone Africa, African countries are asserting their own priorities and renegotiating economic deals with their former coloniser from the perspective of how they will benefit.

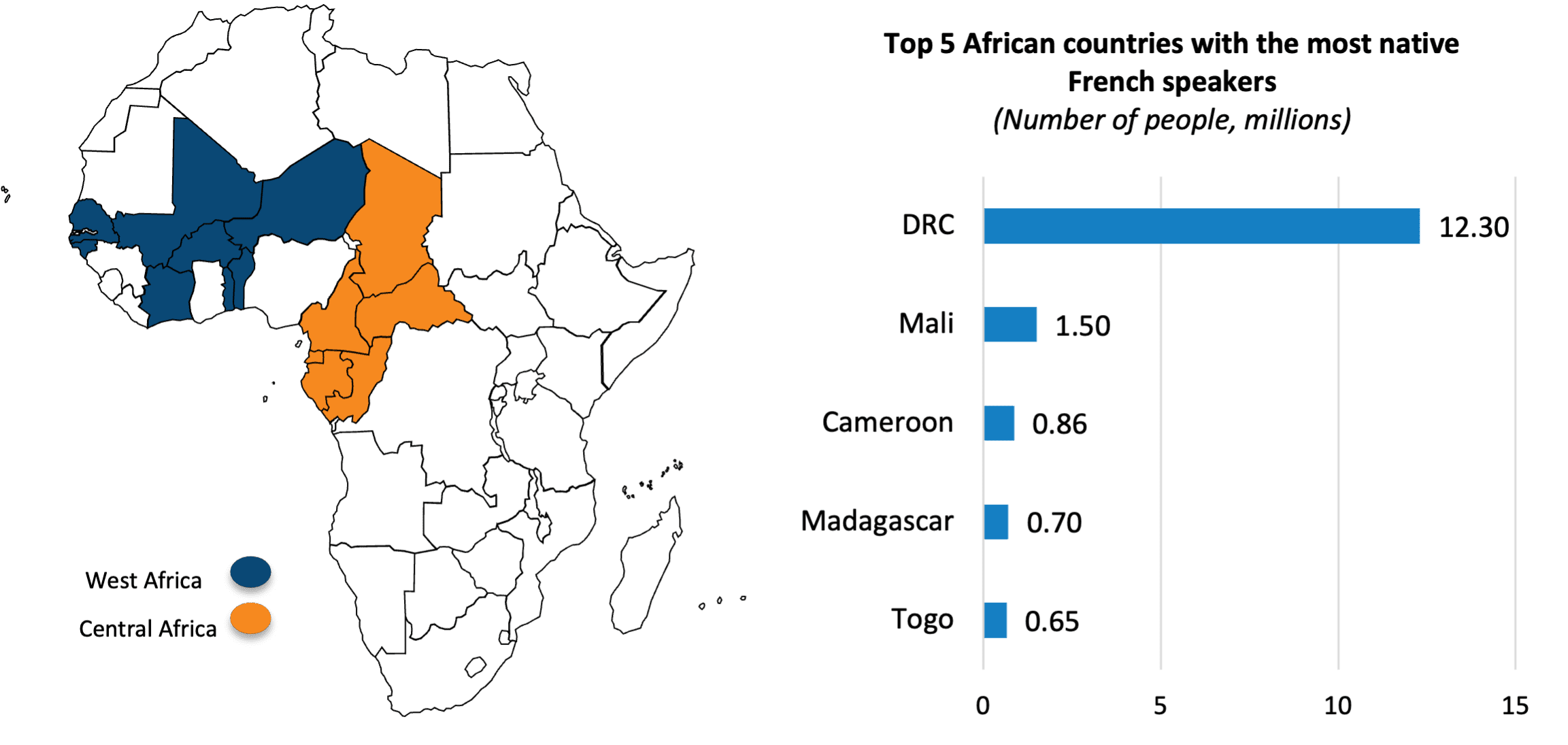

There is great symbolism in the way that Senegal’s President Bassirou Diomaye Faye is delivering speeches. He speaks in the local Wolof language and French. Faye has been in office for one year, elected in April 2024 on the explicit promise to lessen the nation’s dependency on its former coloniser, France. Half of the world’s 300 million French speakers live in Africa, where French is the official language of dozens of countries. However, after military coups overthrew governments in Francophone Burkina Faso, Chad and Mali, their juntas cut military ties with France and downgraded the official position of the French language in their countries. Less dramatically, economic and military ties are being refashioned on a basis more equitable to African partners.

Image courtesy: French Army/ Wikipedia Commons

Two differing approaches to redefining relations with France as a Francophone African nation are exemplified by Senegal and Rwanda. Both approaches involve amicable diplomacy, equality of partnerships and national self-interest. Senegal is one of West Africa’s most politically stable countries, and the government’s linguistic national assertiveness illustrates how sentiments towards France’s influence on Africa is changing. French troops have been in Senegal for 150 years, but Faye asserts the last ones are scheduled to depart by the end of 2025 as part of a West African trend that equates the presence of foreign troops on national soil with the compromising of national integrity. “Senegal is an independent country. It is a sovereign country, and sovereignty does not accommodate the presence of military bases in a sovereign country,” Faye said, indicating that the troop withdrawal was not an anti-France action, rather emphasising that the foreign troops happened to be French.

This change is not a rejection but a modification for self-interest, nor is it nationalism as much as it is an assertion of Senegalese independence. Business and development deals are no longer automatically going to France. The deals are being made with partners who offer packages that best benefit the country. This may be France or China, whichever the country considers their best option. For example, when France declined to finance a new rail system in Tanzania, even though the deal would bolster its presence in West Africa in a non-Francophone country, Dodoma turned to Beijing and struck a deal.

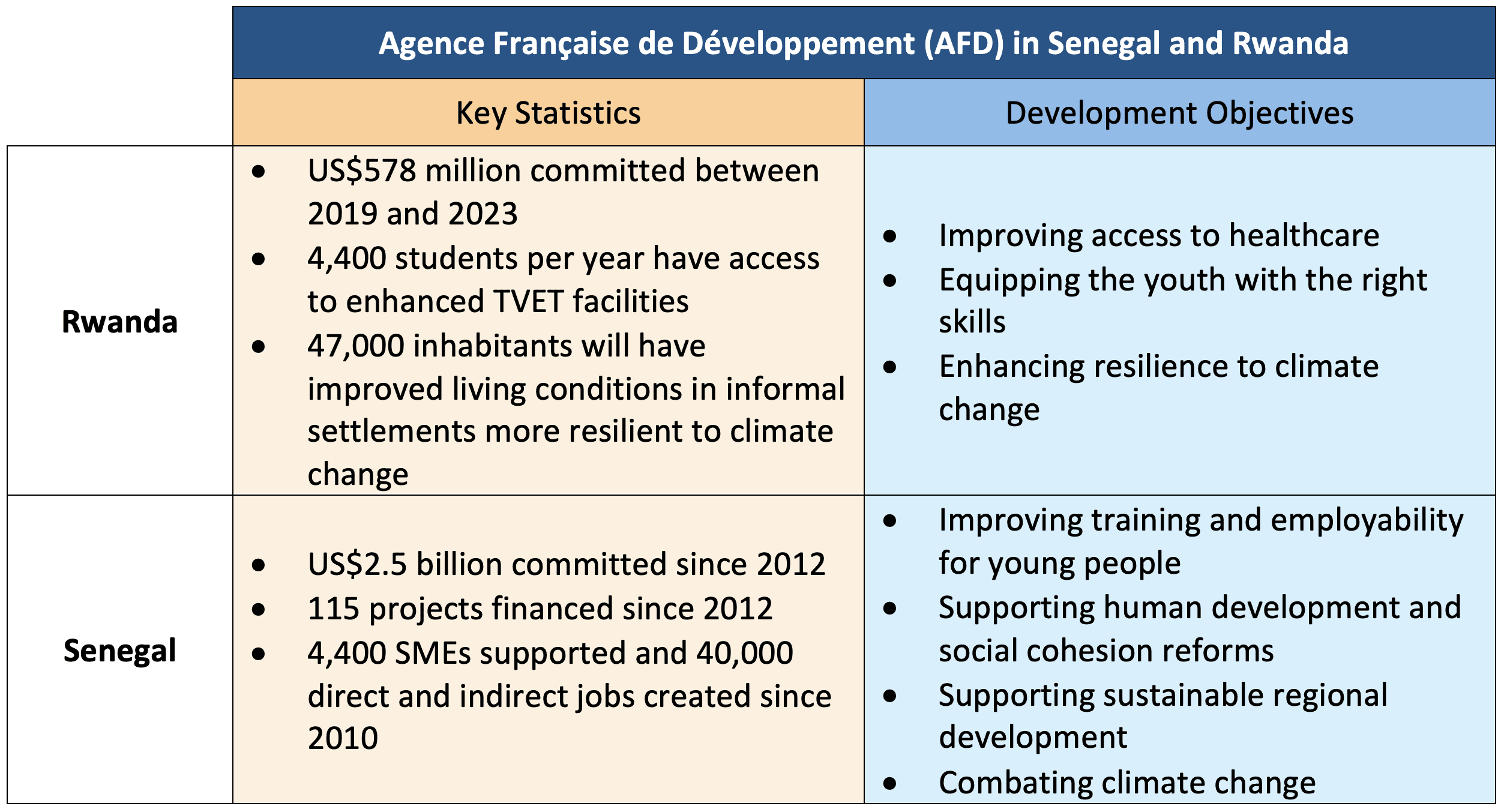

Source: Agence Française de Développement, 2025

On the other hand, France may yet establish a presence in East Africa as a result of its strengthening relations with Rwanda. President Paul Kagame has notably softened his stance towards France, despite long-standing tensions dating back to accusations that he should be prosecuted over his involvement in the 1994 Rwanda genocide. In 2007, Kagame severed diplomatic relations with Paris after a French judge ruled that he must stand trial. However, in 2021, French President Emmanuel Macron formally asked Rwanda to forgive France for its role in the genocide.

By 2024, relations between the two countries had begun to thaw after nearly three decades of hostility. France offered a US$455 million development partnership agreement, increasing its total official development assistance to US$3.75 billion. Kagame, however, still wants more; specifically, he wants improved access for Rwandan exports to the French market and military assistance to support Rwandan peacekeeping efforts in Mozambique. This seems likely due to French energy giant TotalEnergies’ investment in Mozambique’s gas sector of US$20 billion.

France counters claims that its declining military and diplomatic presence in Africa, particularly in West Africa, signals a broader retreat from influence by pointing to the continued strength of its soft power. This influence is reflected in the enduring hold of the French language and culture across Africa, symbolised by the ubiquity of baguettes in Senegalese bakeries. However, the French language represents more than a historic link to France. It also serves as a practical bridge between African countries themselves enabling smoother commerce and tourism.

The second pillar of France’s soft power in Africa, the Communauté Financière Africaine (CFA) franc, is a more complex situation and, for African nations seeking economic independence, a more wearisome problem. With a combined population of 210 million, six Central African countries use the CFA franc, while eight West African countries use the West African CFA franc. These nations enjoy a fixed exchange rate with the euro, and the French Treasury guarantees advances to their central banks to cover temporary shortfalls in foreign reserves, thereby averting balance of payment crises. France also partners with CFA countries on anti-money laundering and anti-terrorist financing initiatives, which are easier to co ordinate under a shared currency. However, the Economic Community of West African States continues to pursue the creation of a common regional currency, modelled after the European Union’s euro. The CFA franc presents a barrier to this goal, causing frustration and rising nationalist sentiments in non-CFA countries like Ghana and Nigeria.

Franco-African relations in 2025 are fluid but increasingly conducted on a more equal footing. This new status quo is driven in part by a rising sense of African patriotism and a desire to finally move beyond the colonial past, but also in part by the realisation that in 2025, as in 1885, Africa remains a continent rich in resources and of strategic importance for France.

Sources: Central Bank of West African States, African Business Insider, 2024