BMC Complementary Medicine and Therapies volume 25, Article number: 214 (2025) Cite this article

Thai traditional medical postpartum care (TMPC) has been an integral part of traditional practices in Thailand for centuries, offering benefits such as bodily restoration and alleviation of postpartum symptoms. Despite its recognized advantages, the utilization of TMPC has currently declined. This study aimed to investigate the factors influencing the intention to use TMPC among pregnant and postpartum women in Bangkok.

A cross-sectional study utilizing a self-administered questionnaire was conducted between September and December 2023 across four hospitals. The data were analyzed using multivariable logistic regression to identify factors associated with the intention to use TMPC.

Among 485 participants, 55.9% expressed an intention to use TMPC (95%CI: 51.3-60.2%). A secondary education or a vocational certificate (AOR = 3.21, CI 1.30–7.95), a bachelor’s degree or higher (AOR = 4.00, CI 1.51–10.58), sufficient income and savings (AOR = 2.11, CI 1.05–4.23), having used TMPC (AOR = 2.88, CI 1.51–5.49), subjective norm scores greater than the 50th percentile (AOR = 1.98, CI 1.17–3.36), and perceived behavioral control scores greater than the 50th percentile (AOR = 4.04, CI 2.44–6.69) were positive factors associated with the intention to use TMPC.

The significant factors of intention to use TMPC were education level, financial situation, prior experience with TMPC, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. Our findings provide the Thai government with important information that they may use to further their campaigns to encourage usage, such as incorporating services of TMPC, like breast massage and herbal compress, into their usual procedures for postpartum women before discharging hospitals so that they can gain a pleasant experience with Thai traditional medicine.

Not applicable.

Postpartum women can face a variety of challenges that impact their physical and emotional well-being. Approximately half of them reported having low back pain, affecting the woman’s quality of life after childbirth. It was also found more in those who had a caesarean section than in those who gave birth via vaginal delivery [1, 2]. Furthermore, about one in four of them had pelvic girdle pain in week 14 after giving birth [3]. Around 65–75% of them reported breast engorgement between 2 and 5 days after the delivery, peaking on the fifth day [4, 5]. Moreover, about 2.5–20% of lactating mothers experienced mastitis during the first to third months of postpartum, while blocked milk ducts were more common in the first month [6, 7]. These breast problems may lead to stop breastfeeding in postpartum women [8,9,10]. Therefore, the postpartum period is a critical phase for maternal recovery and overall well-being.

In Thai traditional medicine, giving birth leads to an imbalance of the four elements (including earth, water, wind, and fire), especially the fire element. The principles of Thai traditional medical postpartum care (TMPC) are to keep the body warm, balance the elements, and restore the body. Traditionally, TMPC comprises laying on a board with hot coals placed next to it, eating hot-taste food, and drinking hot water [11, 12]. Additional treatments are also implemented, such as Thai traditional massage and a hot herbal compress which help stimulate blood circulation, relax muscles, and relieve aching pain [11,12,13,14]; a hot salt-pot compress which helps reduce the uterine level, reduce waist size, relieve uterine pain, and normalize amniotic fluid [11, 15,16,17]; a herbal steam bath which helps stimulate blood circulation, reduce stress, relieve muscular aches, cleanse the skin, clear the airway throughout the respiratory system, and remove extraneous materials through sweating [11, 18, 19]; a breast massage which helps stimulate blood flow to the mammary glands, increase breast milk, prevent mastitis, and treat breast engorgement and blocked milk ducts [7, 9, 20]; and a hot herbal charcoal seat that helps the perineal wound heal [12, 17]. Nowadays, the laying on a board with hot coals and the hot herbal charcoal seat are not used widely anymore. These methods, such as laying by the fire, postpartum massage, and herbal steam bath, are also similar to those used in Cambodia, Laos, Vietnam, Indonesia, Malaysia, and Singapore [19, 21].

Thai traditional medical care emphasizes holistic methods, which focus on restoring balance and harmony in the body, while modern medical practices typically involve clinical assessments, monitoring for potential complications, and evidence-based interventions to promote recovery. Regardless of the difference, both share common purposes, including supporting maternal health and facilitating a smooth recovery after childbirth [17, 22].

Although the Thai government supports TMPC by covering the services under universal health coverage [17, 23], the number of mothers using TMPC at the hospitals was low [24]. A previous study in Taiwan showed that education, occupation, pregnancy-related illness, parity, type of delivery, and breastfeeding had significant effects on using traditional Chinese herbal medicines in postpartum [25]. Moreover, findings in Hong Kong revealed that attitude, subjective norms, and perceived behavioral control positively impacted the desire to utilize traditional Chinese medicine [26]. These factors align with the theory of planned behavior, suggesting that favorable attitudes, positive subjective norms, and higher perceived behavioral control strengthen an individual’s intention to engage in a particular behavior [27]. Other factors can also have an influence on traditional and complementary medicine (TCM) uses. For instance, a study in Macau found that employment status, monthly family income, and breastfeeding-related health problems affected the use of this [28]. In Turkey, a study also discovered that having knowledge about TCM was one of the variables that positively correlated with using it [29]. Therefore, it is important to study whether these factors have any impact on the intention to use TMPC of women. So that the Thai government, related organizations, and health professionals can use the information to promote the uses of the services. Moreover, understanding these factors is not only vital for improving maternal health outcomes but also for preserving and promoting cultural practices that have been part of Thai healthcare for generations.

This study aimed to investigate prevalence and factors influencing the intention to use TMPC among pregnant and postpartum women in Bangkok.

A cross-sectional study using a self-administered questionnaire was conducted between September and December 2023 in the antenatal and postnatal wards of four hospitals in Bangkok, Thailand that provided TMPC, including Siriraj hospital, Klang hospital, Taksin hospital, and Sirindhorn hospital. The participants (1) were ≥ 18 years old, (2) were pregnant women who had a gestational age of 14 weeks or more, or postpartum women who received general postnatal services before discharging from the hospital, (3) were Thai citizens, (4) had no history of serious illness, and (5) had no serious obstetric complications. They were recruited for this study using a purposive sampling technique. The required sample size was calculated using Cochran’s formula [30]. We assumed the proportion of women who use TMPC after giving birth was 12% (p = 0.12) [31], level of significance 5% (α = 0.05), Zα/2 = 1.96, and absolute precision or margin of error 3% (𝑑 = 0.03). Based on a prediction of the number of participants who may answer the questionnaire incompletely, the sample size was increased by 10%.

The outcome variable was the intention to use TMPC, measured as a binary response (yes/no). Independent variables included socio-demographic factors (age, marital status, pregnancy-related illness, education level, occupation, financial status, and health security system); obstetric factors (current maternal status, number of pregnancies, history of caesarean section, and breastfeeding experience); and service-related experiences (previous awareness of TMPC and prior use of TMPC), as well as knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. All independent variables were treated as categorical variables in the analysis.

A structured questionnaire that was specifically developed for this study was employed to gather data, as can be seen in Supplement 1. Four specialists with backgrounds in Thai traditional medicine, obstetric nursing, or public health evaluated its content validity. Subsequently, the questionnaire was tried out with 30 samples to ensure its reliability before being utilized. The reliability coefficients for the part of knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control were 0.811, 0.827, 0.953, and 0.809, respectively. The questionnaire included five parts. The first part gathered socio-demographic data and obstetric history, comprising 10 questions designed to collect relevant background information. The second part explored participants’ experiences with TMPC. There were 2 questions on whether the participants had heard of TMPC or had utilized it. The third part evaluated participants’ knowledge of TMPC through 15 questions, including the principle of TMPC (1 item), general knowledge (5 items), treatment methods (2 items), effectiveness (2 items), common concerns (4 items), and recommendations (1 item). The options for answers included “True”, “False”, or “Do not know”. One point was given for a correct answer, while zero points were given for an incorrect one or “do not know”. The fourth part, which consisted of 15 questions, examined attitude (4 items), subjective norm (6 items), and perceived behavioral control (5 items) using the questionnaire adapted from previous literature [26]. In this part, the answers were scored on a 5-point Likert scale from 1 (very strongly disagree) to 5 (very strongly agree). The scores of knowledge, attitude, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control were categorized into two groups by the 50th percentile. The last part explored participants’ intentions to use TMPC, the reasons for choosing not to use it, and their awareness of their rights to access TMPC.

The data were analyzed using SPSS version 28. Frequency and percentage were used to describe the characteristics of the participants. The association between factors and intention to use TMPC was assessed using binary logistic regression analysis. The assumptions for multivariable logistic regression were checked prior to analysis. The Variance Inflation Factor (VIF) for all independent variables was below 1.8 and all tolerance values were above 0.1, indicating no multicollinearity. The assessment of multicollinearity is shown in Supplement 2. Additionally, the data was reviewed for duplicate responses and clustering, and no issues were found, confirming the independence of observations. Subsequently, we generated a multivariable logistic regression model using variables with a p-value of less than 0.2 from bivariable analysis. The adjusted odds ratio (AOR) was calculated using a 95% confidence interval (CI). The value of statistical significance was set at p-value less than 0.05.

This study included 485 participants. Demographic characteristics of participants are summarized in Table 1. The average age was 28.85 ± 6.46 years. Pregnancy-related diseases affected around a fifth of the participants (21.6%), with gestational diabetes accounting for over half (64.8%) of these cases. Interestingly, although most participants (83.9%) had heard about TMPC before, but only 15.9% had ever used it.

The knowledge score ranged from 0 to 15. The average score was 5.24 ± 3.17. More than half (54.4%) of the participants had a knowledge score less than or equal to the 50th percentile. This reflected that most participants had limited knowledge about TMPC. A summary of participants’ responses to questions regarding knowledge of TMPC is presented in Supplement 3. The average of the attitude scores was 3.94 ± 0.71. Nearly two-thirds (64.9%) had an attitude score less than or equal to the 50th percentile. The mean of the subjective norm scores was 3.84 ± 0.73. About half (51.8%) had a subjective norm score less than or equal to the 50th percentile. In terms of perceived behavioral control, around three-fifths (58.4%) had a score less than or equal to the 50th percentile, and 3.42 ± 0.69 was the average score.

There were eleven factors significantly associated with the intention to use TMPC, as shown in Table 2. However, in the multivariable logistic regression analysis, only five factors were statistically significant. Participants who had “a secondary education or a vocational certificate” and “a bachelor’s degree or higher” were 3.21 (AOR = 3.21, CI 1.30–7.95) and 4.00 (AOR = 4.00, CI 1.51–10.58) times more likely to intend to use TMPC than those who had a primary education or lower, respectively. Those who had sufficient income and savings were 2.11 times more likely to intend to use TMPC as compared to those who had no sufficiency (AOR = 2.11, CI 1.05–4.23). Moreover, those who had used TMPC were 2.88 times more likely to intend to use it again (AOR = 2.88, CI 1.51–5.49). Participants who had subjective norm scores and perceived behavioral control scores greater than the 50th percentile were 1.98 (AOR = 1.98, CI 1.17–3.36) and 4.04 (AOR = 4.04, CI 2.44–6.69) times, respectively, more likely to intend to use TMPC as compared to those who had the scores less than or equal to the 50th percentile, as presented in Table 3 (Model 1). Each odds ratio was adjusted for education level, financial status, ever used TMPC, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control. These factors were statistically significant, as shown in Table 3 (Model 2).

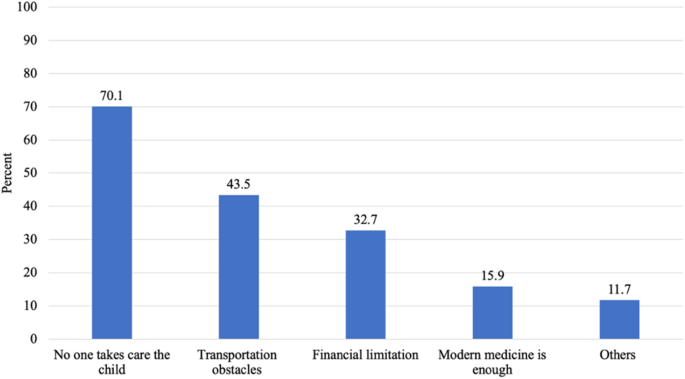

This study found that the intention to use TMPC was 55.9% (95%CI: 51.3-60.2%), while 214 (44.1%) of all participants indicated no intention to use it after giving birth (95%CI: 39.8-48.7%). There were many reasons for not intending to use TMPC, as shown in Fig. 1. The leading reason was that no one would look after the child while the mother had to receive TMPC. One-third of those who intended to not use TMPC cited financial problems as the reason. Other reasons included the absence of information about TMPC, misunderstanding that women who had a caesarean section or sterilization surgery could not use TMPC after giving birth, and returning to work.

Interestingly, only 102 (21.0%) of all participants knew that women who have universal coverage can get the services to rehabilitate the body after giving birth free of charge when queried about their awareness of this right.

TMPC is beneficial to a woman’s health after giving birth. However, it has been shown that there remain few uses. Therefore, this study was designed to survey the prevalence and factors associated with the intention to use TMPC among pregnant and postpartum women in Bangkok. The prevalence of intention to use TMPC found in our study (55.9%) was lower than previous studies from Malaysia (66.2–85.7%) [32, 33], where a higher proportion of women actually used TCM during the postpartum period. Similarly, a study from Taiwan [25] found that 87.7% of postpartum women used at least one form of Chinese herbal medicine, suggesting a strong preference for traditional healing practices. The differences in prevalence rates between the studies may reflect variations in belief, societal norms, and the level of integration of traditional practices within the healthcare system. Additionally, the generational health advice of TCM contributes to its enduring prominence in certain countries. While the intention to use TMPC in our study is substantial, it is important to consider that intention does not always translate into actual use, which may be influenced by factors such as availability, accessibility, and affordability, as well as healthcare provider recommendations [32, 34].

There was an association between education levels and the intention to use TMPC. The education level of higher than or equal to secondary or vocational had a greater effect on the intention to use the services. This might be because people with higher education were more aware of the importance of taking care of their health. This result is in line with findings from several studies. It is possible that women who had higher education were better in making informed decisions and searching for health information, which in turn led to a rise in the number of health-seeking behaviors [25, 29, 35,36,37].

Women with sufficient income and savings were more likely to use TMPC than those with insufficient income. Moreover, our study showed that the third most common reason for not obtaining TMPC was financial issues, which accounted for 32.7% of those who expected not to utilize the services. This was consistent with a study in Myanmar [35] and China [38] that one of the main obstacles to utilizing postpartum care services was financial difficulty. Furthermore, income levels have been shown in various studies to impact women’s autonomy in making decisions on health care [37]. Since our findings indicated only one in five participants knew that women with universal coverage can receive the services to rehabilitate the body after giving birth free of charge at the healthcare setting according to their rights. Therefore, providing this information to postpartum women may encourage their intention to use TMPC.

We found that there was a statistically significant relationship between experience in using TMPC and intention to use. It might be because they knew information about the benefits, procedures of the services, and places. These give them enough information to use TMPC again. This outcome was in accordance with a Korean study showing that 98.5% of women who had previously received the herbal decoction for postpartum care expressed a desire to use it once more [39]. Similarly, a study in Saudi Arabia found a significant relationship between previous usage of herbal medication and usage during pregnancy. In addition, it was found that using herbal medication during pregnancy led to increased uses after the delivery. The prevalence of using herbs during pregnancy, during labor, and after delivery was 25.3%, 33.7%, and 48.9%, respectively [40].

This study indicated that recommendations and support from family, friends, and public health personnel had a great positive effect on the intention to use TMPC. It was in line with previous studies in Hong Kong [26], Malaysia [33], and Cambodia [41]. This might be attributed to the influence of subjective norms or social factors, which are deeply embedded in daily life and significantly impact individual behavior. In the context of health-related decisions, individuals frequently seek guidance from trusted sources such as parents and healthcare professionals. These individuals are regarded as credible due to their expertise and experience. In situations characterized by uncertainty, individuals are especially inclined to follow the advice or behavior demonstrated by those they trust. Moreover, positive reinforcement from social factors regarding the importance or efficacy of service care can strengthen one’s intention to use [27, 42].

Finally, a positive self-perception had a greater impact on intention to use TMPC. Perceived behavioral control describes how easy or difficult a behavior is considered to be to do. It is believed to be affected by prior behavior, as well as predicted barriers and difficulties [27]. In addition, beliefs about control have been linked to health behavior, health outcomes, and health care. Generally, the greater one’s sense of control, the more likely one is to behave appropriately and achieve better results [43, 44]. This was consistent with several researches from Hong Kong [26] and Australia [45].

There were several strengths in our study. Firstly, our results were obtained from four hospitals that provide TMPC in various districts of Bangkok. So, it could represent pregnant and postpartum women in Bangkok. Secondly, the questionnaire was validated by four experts who covers all aspects related to this study. Nevertheless, since the study design was a cross-sectional study, therefore judgments about the causality of the association between influencing factors and the intention to use TMPC cannot be drawn.

Education level, financial status, experience in using TMPC, subjective norm, and perceived behavioral control were the statistically significant factors of intention to use TMPC in Bangkok. Our findings can be beneficial in planning strategies to promote postpartum care with Thai traditional medicine. The ministry of public health can launch a directive requiring hospitals that provide TMPC to display public notices on information boards or social media platforms, or to have ward nurses verbally inform women who have given birth that TMPC provided in public health facilities is covered by Thailand’s universal health coverage. This approach would address financial barriers that hinder access to the services. Moreover, the hospitals should provide basic information about TMPC, its benefits, and common misconceptions. For instance, women who have had a caesarean section or sterilization surgery can use TMPC one month after giving birth. Before being discharged, hospitals should incorporate a visit to a Thai traditional clinic into their regular schedule. This might provide the postpartum women and their family members experience and raise the subjective norm. Social campaigns and community-based health programs that involve influential community leaders or respected family members can also encourage the use of TMPC. As a result, this could help the country to reach its public health goals to promote the use of Thai traditional medicine, alternative medicine, Thai wisdom and herbs, and to increase the rate of access to Thai traditional medicine and alternative medicine services to 100% by the year 2036. Furthermore, our findings can be utilized to delve deeper into contextual factors that shape individuals’ intentions and behaviors regarding TMPC. For instance, longitudinal studies can track changes in intentions and actual usage over time.

All datasets supporting the outcomes of this investigation are reachable from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

- AOR:

-

Adjusted odds ratio

- CI:

-

Confidence interval

- TCM:

-

Traditional and complementary medicine

- TMPC:

-

Thai traditional medical postpartum care

The authors are deeply indebted to the hospital directors and staff at Siriraj hospital, Klang hospital, Taksin hospital, and Sirindhorn hospital for allowing data collection and providing a warm welcome. We would like to extend our sincere thanks to Dr. Natchagorn Lumlerdkij for suggestion in writing. Lastly, we would be remiss in not mentioning all the participants in this study.

This research was supported by the 90th Anniversary of Chulalongkorn University Fund (Ratchadaphiseksomphot Endowment Fund).

This study was implemented in accordance with the principles established in the Declaration of Helsinki. It was reviewed and approved by “Siriraj Institutional Review Board, Faculty of Medicine Siriraj Hospital, Mahidol University” with SIRB protocol No. 550/2566 (IRB1), “The Research Ethics Review Committee for Research Involving Human Research Participants, Group I, Chulalongkorn University” with COA No. 177/66, and “BMA Human Research Ethics Committee (BMAHREC)” with a reference number of U023hh/66_EXP. All participants in this study provided written informed consent.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Sirichai, L., Leenatom, K., Jiranorrawat, C. et al. Factors influencing the intention to use Thai traditional medical postpartum care among pregnant and postpartum women in Bangkok: a cross-sectional study. BMC Complement Med Ther 25, 214 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-025-04960-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12906-025-04960-5