By the end of 1995, the web moved outward and into the hands of everyone.

This is the final post in a sort of series about 1995. Part 1 dealt with the ideological split that occurred that year. Part 2 discussed that year’s innovative design work. This installment is about the way the web spread outward, and into the hands of everyday people.

It’s not necessarily easy to create a website. It requires, at the bare minimum, a knowledge of the HTML markup language, and the ability to host these HTML files in such a way that they can be read by web browsers. It takes a bit of work. But anyone with the tools and some time can do it. In 1995, the web was flooded with new websites. Remember, there were hundreds going up every day. Some of these were large commercial endeavors. Others were the creative brainchildren of wildly unique creators like Jamie Levy. Most of them were built by ordinary people. They were basic and loosely connected and sometimes about TV shows or movies or nothing at all. Maybe even you built one of these.

The web wasn’t under lock and key. No one dictated what populated it (though it may feel like that given the homogeneous and largely commercial experience of browsing the modern web). If you had an idea for a website, you tossed it up on a server and sure, maybe nobody would see it, but at least it was there and it was yours. There were all sorts of websites. Big ones, small ones, fan pages dedicated to B and C-List celebrities, personal diaries and long, rambling thesis’ about everything. Purple.com was a website that was just a blank, purple page. That’s all there was too it and it was wildly popular. Sites like these were a large percentage of actual websites, the long tail of the web. We don’t think about it much, but even with the billions of Facebook profiles, they still kind of are.

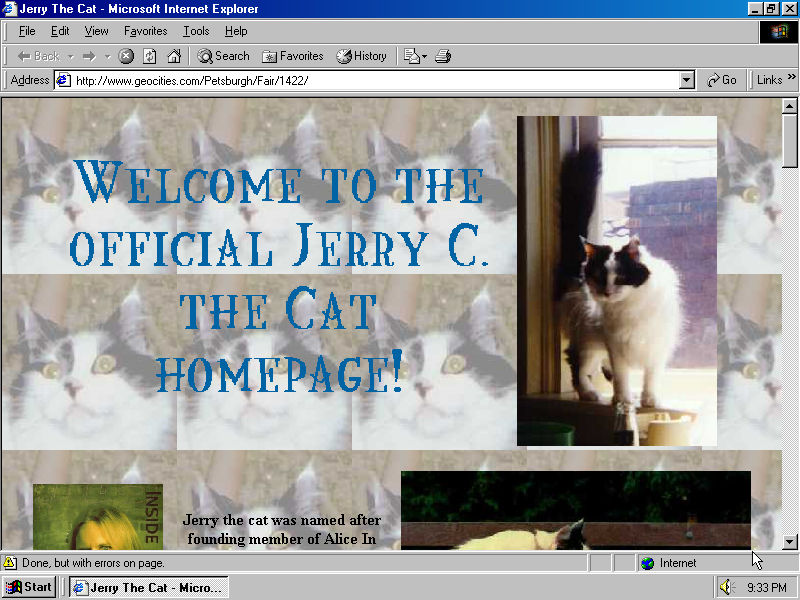

There were lots of weird little experiments that gave rise to these websites too. Geocities popped up at the end of 1994, originally under the moniker Beverley Hills Internet. It was one of a number of other sites that came for it, like Myspace and Neopets, that empowered users to use code to create something on the web without having to know too much about how it all worked. Geocities hooked users in with a simple gimmick. The site was divided into several different virtual “neighborhoods,” named for actual, IRL neighborhoods, like Beverley Hills, or more abstract concepts like the science fiction themed Area51. As a user, you could set up your own site in any of these neighborhoods. You didn’t have to stick to the theme of the neighborhood, but it was a pretty neat entry point.

The level of creativity and versatility on display on your average Geocities site is hard to understate. Most were a cross between amateur experiments and love letters to this or that piece of pop culture. They were plastered with recipes, vacation photos, esoteric images, and tidbits of slash fiction. Getting up and going on Geocities required a bit of HTML, but once you played around a bit, it was easy enough to build just about whatever you wanted.

Look at how developer Benj Edwards recalls building his own site in 1995:

At that time, Netscape 1.0 did not support background images (all pages had a grey background), did not display JPEG images at all, or allow HTML-selectable font faces–among other limitations. But we liked it anyway.

It did, however, support displaying GIF files inline with text. So to make a snazzy logo for my new website, I fired up Microsoft Paintbrush and sketched out a geometrical wonder… After that, it was time to add the image tag to my HTML file, then upload it to my web space and check it out online for the first time.

Little by little, these small clusters of writers and artists and web folk began to spring up. Webgrrls was founded in 1995 too, and it gave women interested in the web a platform and a community to get started. It was the springboard for more than a few careers. Newgrounds, launched that summer, offered up an entirely different scene of aspiring animators and game designers who used the web to share their work without the need for a publisher or a means of distribution. The work was occasionally rough around the edges, but buried within were some true gems.

What’s a bit hard to see these days is how uncertain the future of the web was. No one really knew what we were going to do with this massive global network of digital identities held together with little more than spit and glue. Some were figuring it out on the ground, building sites in their spare time to figure out how it all worked. Others were trying to take it to take that to the next level.

Think back to the first website you ever saw. We all had very different entry points into the World Wide Web, but I’m guessing if you’re reading this newsletter, it was a transformative experience for you. If you were cool (or, let’s face it, geeky) enough to be surfing the web in 1995, that site might have been Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web.

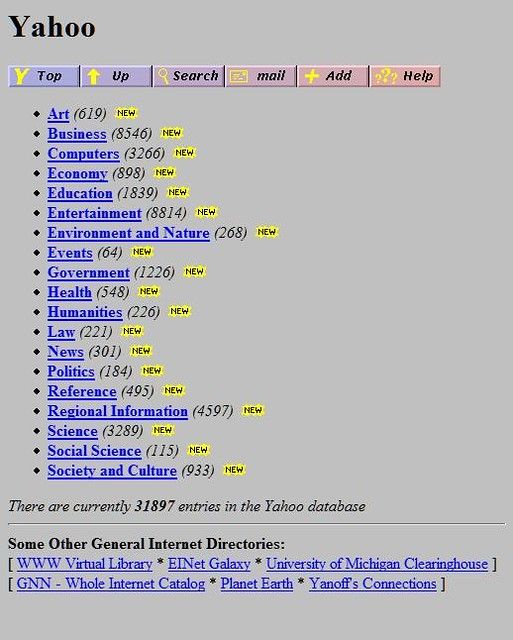

That particular’s website’s backstory starts in early 1994, when electrical engineering majors Jerry Yang and David Filo felt compelled to procrastinate on their latest research project on circuit designs. As students do. Instead of all that boring researching, they dived down a rabbit hole of hyperlinks on the World Wide Web and got themselves hooked, almost instantly. Pretty soon though, they lost their way and found it hard to find new sites without some serious digging through the interwebs. It was easy enough to jump from one site to the next, but there weren’t any collected lists that were particularly canonical or exhaustive. The two turned their attention to learning about the web, and in a few weeks they had assembled their very own website, one that was a simple list of links to other websites.

The site, Jerry and David’s Guide to the World Wide Web (named eponymously), was a massive collection of links organized into sometimes bizarre and eclectic categories. These categories made little sense outside of Jerry and David’s brains, but they clicked almost immediately with the offbeat attitude of early web adopters that managed to find the site. It became a point of discovery for many web users, a jumping off point into the endless abyss of the web, providing clarity where once there was only darkness. By January of 1995, they moved the site to the domain Yahoo.com, got featured inside of the Netscape browser, and became a portal to the web for millions of users.

Of course, that story’s not true, not all of it at least. It’s not fundamentally incorrect or disingenuous, but it leaves out some pretty important details. Here’s the truth. The first online directory of sites was actually the first website Berners-Lee ever created. It was hosted on CERN servers, and maintained and updated daily by Berners-Lee himself. It’s an idea that was later extended by Dougherty and his team at GNN. By the time Yang and Filo started tinkering around with a web directory of their own, GNN had been in business for over a year, had inked deals with the Netscape browser and lucrative ad partners, and had expanded their team inside of O’Reilly. Yahoo was a reimagining of the GNN concept, in methodology if not in all out practice. Yahoo was a bit more homegrown, maybe even more down to earth, with a rawer aesthetic than the more refined look GNN had settled on after years of experimentation. But it was fundamentally similar.

That’s not how they were sold though. Yang and Filo were stalwarts of a particular brand of Silicon Valley tech-genius lore. It’s not a mythology they invented, nor were they particularly responsible for spreading it. They did, however, embody that mythology as it manifested on the web. In a 1995 profile of the company for Rolling Stone, Amy Virshup articulates the way in which the story of Yahoo echoed that of virtually every other web startup.

Theirs is a fable becoming almost common in Silicon Valley in these days of overheated expectations for the Internet. A couple of guys with pocket protectors and a glint in their eyes invent some garage software, round up some venture-capital financing and go on not only to make millions but also to change the outlines of the world, at least technologically speaking.

Yahoo, which took off just before 1995 got started, laid down a foundation for other tech startups with the same kind of hyped expectations to burst on the scene. Each site that sprung up did so from its own mythic roots. It was that very year that Pierre Omidyar launched a makeshift auction site to help his girlfriend sell Pez Dispensers online and called it Ebay, a story that is somewhat grounded in truth. It was the year that, alone in his garage, Jeff Bezos made selling books online an overnight success, a story that leaves out the years of work and fortuitous connections that Bezos had developed.

Encouraged by the efforts of online shopping pioneers, Jeff Bezos tries his own hand at an online store, choosing Amazon.com for its early prominence in alphabetical directory listings.

If 1995 was a year of creative expression that begot sites like WORD and The Blue Dot, it was also the year the web found commercial viability. Forward thinking investors began to see the potential of the web, with its global reach and low startup costs, as a place to begin appealing to a mainstream audience. A lot of businesses that got started then still exist today. And 1995 was also the year of sites like Altavista and Lycos, which used automation to crawl and index sites on the Internet, highlighting the fact that the web was beginning to spread far beyond the isolated echo chambers of its origins.

Right as 1996 began, Jennifer Robbins published her first book, collecting the things she had learned working on GNN into a step by step guide called Designing for the Web. That same month, Lynda Weinman published her own web design book, Designing Web Graphics alongside her online learning resource and seminar series Lynda.com. Together, they created the perfect endocarp to a turbulent and transformative year, the first official handbooks for the digitally curious web aficionado.

If you were fortunate enough to be working on the web in 1995, it may have felt far more insignificant at the time. Most people were just playing around the web because they thought it was cool, and when they got online they found an entire community just like them. People began to craft their online identities, and share links, words, and experiences with one another. The cumulative effective, though, was a web that began to spread into the hands of everyone. One by one, as users blinked online for the first time, the web gained a stronger foothold, a starting point that would soon be used to catapult the web into a large-scale commercial endeavor. For now though, it was a fun place to be with very little rules and near infinite possibilities. It was a home for many that had previously felt lost, and that is a powerful thing.