Debt Service Strains Africa's Capacity to Tackle Climate Change - Ecofin Agency

The continual rise of Africa's debt service is curtailing the continent's budgetary space for essential investments like education, healthcare, and climate change mitigation, according to a recent report from the Institute for Economic Justice (IEJ). This South African-based think tank is committed to promoting economic justice and equitable distribution of resources globally.

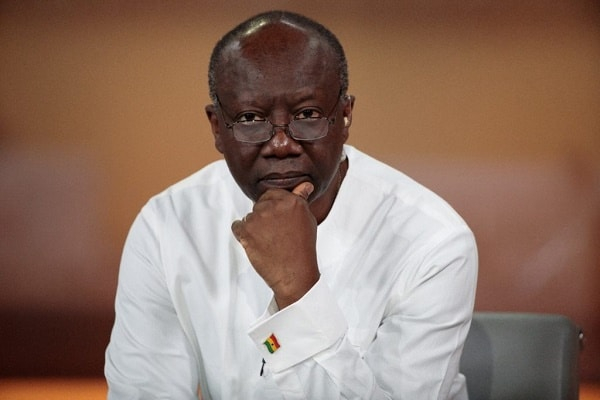

Titled "Diverting Development: The G20 and External Debt Service Burden in Africa", the report reveals that each African country's debt service to climate financing needs ratio differs, with particularly high rates in The Gambia (3259.5%), Gabon (278.4%), Ghana (258.2%), Senegal (187.7%), Côte d'Ivoire (187.2%), and Sao Tomé and Principe (150.1%).

Although Africa's total external debt is relatively modest, at $746 billion or 25% of the continent's GDP, debt service payments have reached their highest level since the early 2000s debt crisis. The African Development Bank Group estimated that African governments devoted $163 billion to debt service in 2024, a significant increase from the $61 billion spent in 2010.

In 2023, debt service constituted 16.7% of public revenues and 14.8% of total export revenues. In the same year, interest payments alone equaled 4.7% of export earnings. Naturally, this diverts necessary resources from investing in health, education, and other priority sectors. About 751 million Africans, or 57% of the continent's total population, live in countries that devote more resources to external debt service than to healthcare expenditures. Similarly, at least 30 countries on the continent spend more on debt interest service – excluding principal repayments – than on public health.

The escalation in debt service can be attributed to the increased principal repayments and the higher borrowing cost – the result of Africa's growing dependence on commercial loans on top of concessional financing. While the World Bank's share in Africa's debt has remained almost constant at just under 20% between 2008 and 2023, and that of the African Development Bank has steadied at around 7%, Eurobond holders have become the dominant creditor class.

In 2008, Eurobond holders only held 12% of the continent's external debt ($25 billion). However, their share climbed to 25% in 2023 ($186 billion).

The other significant trend observed during this period is the rising prominence of China among bilateral creditors, its share growing from 4% in 2008 ($7 billion) to 8% in 2023 ($62 billion). At the same time, Paris Club members, who often offer highly concessional rates to African countries, saw their share drop from 28% ($57 billion) to just 6% ($48 billion).

As a result of Africa's growing reliance on debt held by active investors in the bond markets, the continent's borrowing cost is significantly higher compared to developed countries and even some other developing regions. In 2023, the average bond yields were 9.8% in Africa, versus 5.3% in Asia and Oceania, and 6.8% in Latin America and the Caribbean.

The report also criticizes various debt relief mechanisms established by the group of the world's twenty most developed economies (G20), like the Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) and the G20 Common Framework for Debt Treatments, labeling them as slow and largely ineffective. These mechanisms provide only minimal debt relief, which hinders beneficiary countries from embarking on new development paths and does not guarantee fair participation from all creditor classes.

In response, the Institute for Economic Justice proposed a series of measures to reduce these inefficiencies and sustainably lighten African countries' debt burden. Among these proposals is an automatic two-year debt service moratorium whenever a country requests debt restructuring under the G20 Common Framework, preventing the accumulation of interest during negotiations to incentivize all creditors to participate, adjusting debt relief amounts based on an improved 'Public Debt Sustainability Analysis' (DSA) that includes climate risks and investment needs to ensure adequate capacity for long-term recovery, and expanding eligibility to the Common Framework to middle-income and emerging markets facing debt problems.