DCI Phone Tracking & Ndiang'ui Case Controversy

Software engineer Ndiang’ui Kinyagia dramatically reappeared before the Milimani Law Courts in Nairobi on July 3, 2025, alive and well, 11 days after he was allegedly abducted by the Directorate of Criminal Investigations (DCI). His resurfacing culminated a high-stakes legal drama that had even prompted a court summons for DCI boss Mohammed Amin. Despite his appearance before Justice Chacha Mwita, the specific circumstances of his disappearance remained shrouded in mystery, raising uncomfortable questions about state surveillance.

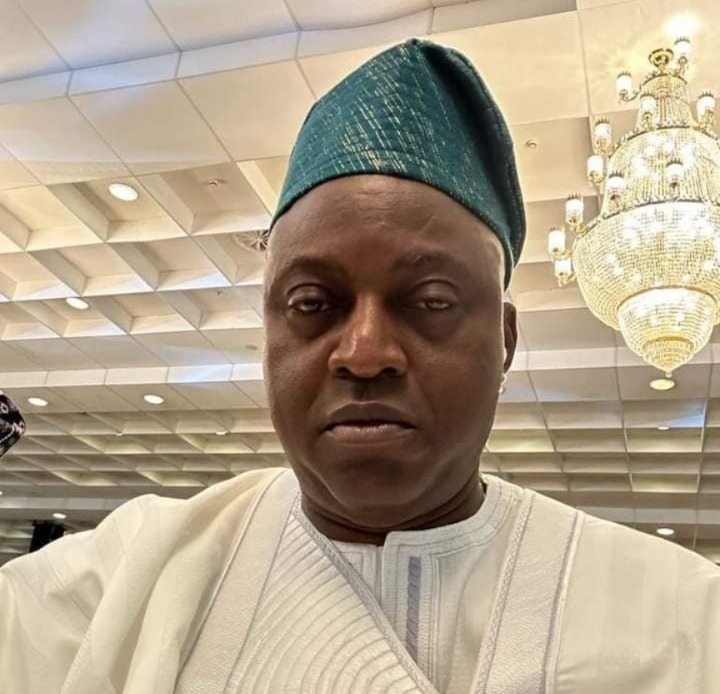

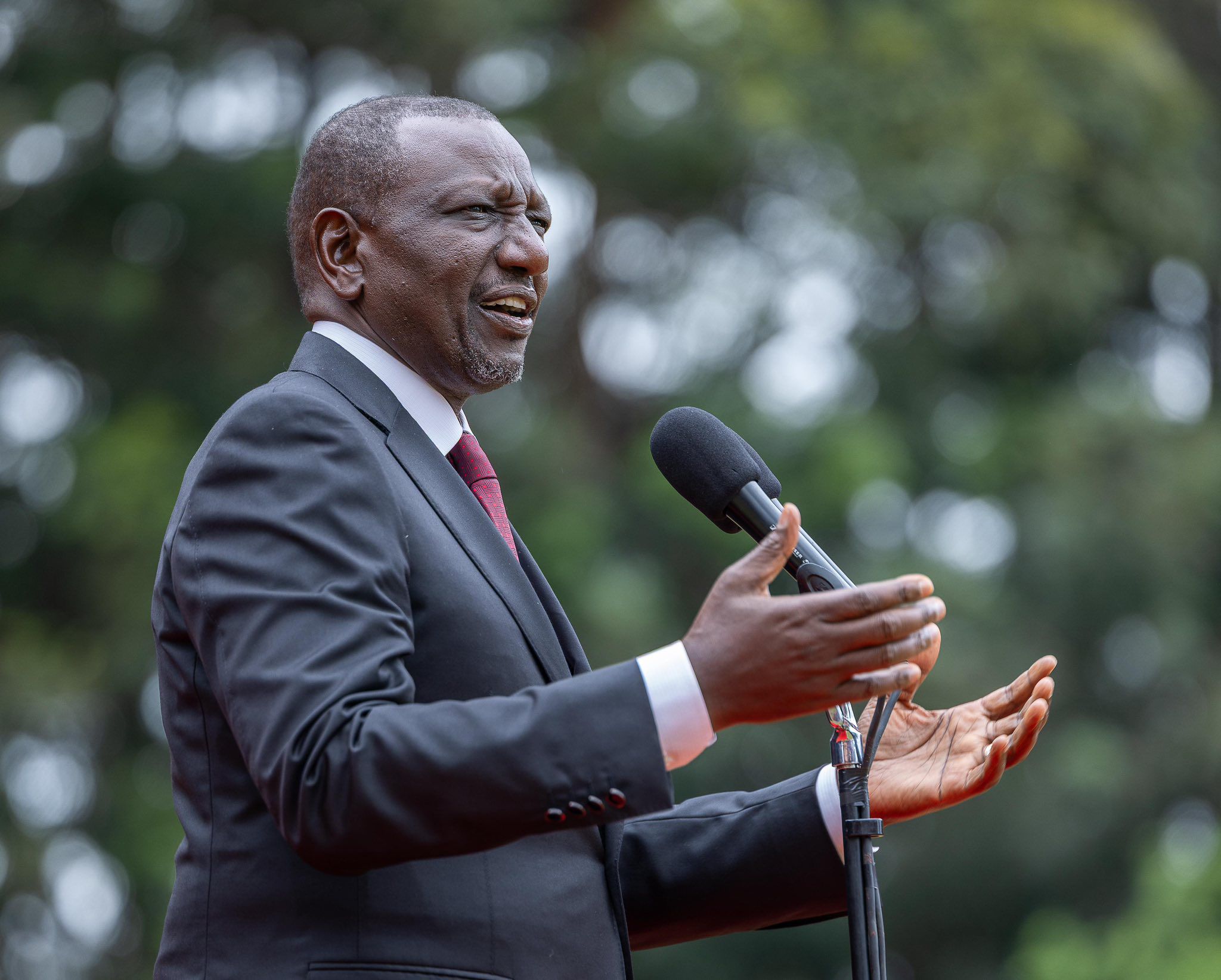

During the court proceedings, DCI boss Mohammed Amin, represented by Senior State Counsel Emmanuel Bitta, protested what he termed as unfair vilification of the DCI regarding Ndiang’ui’s disappearance. Bitta argued that the directorate had not been given a fair opportunity to present its side. After nearly three hours of intense exchanges, Justice Mwita issued crucial orders: police were not to arrest Ndiang’ui until further court directives, and he was permitted to seek medical attention, record a statement with the DCI if necessary, and privately consult with his family and lawyers about the 11 days he was missing. Justice Mwita emphasized his primary intention was to present Ndiang’ui alive to Kenyans, with other matters to follow.

Ndiang’ui’s legal team painted a picture of a traumatized individual. His family lawyer, Kibe Mungai, informed the court that Ndiang’ui had called his lawyer cousin, Lilian Wanjiku Gitonga, from an undisclosed location, expressing deep fears for his life. Similarly, lawyer Wahome Thuku, also representing Ndiang’ui, stated that his client had gone into hiding "for fear of his life" after allegedly learning he was a person of interest to DCI officers. Lawyers Martha Karua and Mwaura Kabata of the Law Society of Kenya urged the court to allow them to question Amin directly about the increasing number of alleged abductions, asserting that such answers would greatly assist the court in upholding the rule of law. Willis Otieno, another lawyer for Ndiang’ui, pressed for an order preventing his arrest, citing the DCI's classification of him as a person of interest.

The National Police Service (NPS), through police spokesperson Muchiri Nyaga, swiftly dismissed the abduction claims as "false and misleading" following Ndiang’ui’s reappearance. The NPS maintained that Kinyagia was never in their custody and directed him to present himself at DCI Headquarters to record a formal statement, reiterating that he remained a "person of interest." Furthermore, the NPS expressed significant concern over what they described as a "troubling trend" of individuals allegedly faking disappearances to manipulate public opinion and discredit law enforcement. They warned that stage-managing abductions or providing false information are criminal offenses punishable by law, undermining police integrity and causing public anxiety. Sergeant Patrick Bwire of the Kikuyu Sub-County DCI office also claimed Ndiang’ui’s family had not filed a formal missing person report, though a relative, Margaret Rukwaro, did report him missing at Kinoo Police Post, with a follow-up by Lilian Kithinji and Ndiang’ui Kithinji days later. The case is scheduled for further hearings on July 18 and 24.

The incident cast a harsh light on the Directorate of Criminal Investigations' advanced surveillance capabilities. The DCI possesses tools to secretly track mobile phones, including IMEI tracking, cell tower triangulation, and access to call detail records (CDRs). This surveillance is reportedly used during investigations into serious crimes, often with cooperation from mobile service providers. A data specialist, speaking anonymously, explained that surveillance typically begins when someone becomes a suspect, often triggered by a tip-off or suspicious online activity. Police are ostensibly required to record a complaint and open an Occurrence Book (OB) before initiating surveillance.

CDRs, which investigators often request, ideally with a court order, contain extensive data beyond just call logs. They include MSISDN (phone number), ICCID (SIM card serial number), IMEI (device serial), call and text timestamps, BTS (base transceiver station) locations – which are the mobile towers a device connects to – and a list of frequently contacted numbers. By analyzing BTS data, investigators can triangulate a person’s movements, as a phone signal pings the nearest tower whenever a call or SMS is made. The SIM card, with its unique IMSI identifier, coupled with the device’s IMEI, creates a comprehensive digital footprint of calls, messages, data usage, and location, essentially turning the device into a personal tracker. Even basic "kabambe" (feature) phones are traceable, connecting to mobile networks and generating tower data, regardless of lacking apps or GPS.

Despite these sophisticated tracking systems, Ndiang’ui Kinyagia, a 35-year-old IT expert, managed to evade detection by deliberately leaving his gadgets – including phones and laptops – at his Kinoo home and going completely off-grid. For the entire duration of his disappearance, the DCI was unable to trace him, a fact acknowledged by DCI Director Mohammed Amin, who merely stated Ndiang’ui was not in police custody but was a person of interest. Experts like George Musamali, a former General Service Unit instructor, emphasized that while tracking is intended to combat crime, its widespread abuse poses risks to innocent citizens, underscoring the critical need for valid court orders before any individual is tracked. The National Police Service's warning against faked abductions further complicates the narrative surrounding Ndiang'ui's 11-day disappearance, leaving many questions unanswered regarding the interplay between personal safety, state surveillance, and legal accountability in Kenya.