Data Shows Attendance Improves Student Success

Prior research shows attendance is one of the best predictors of class grades and student outcomes, creating a strong argument for faculty to incentivize or require attendance.

Attaching grades to attendance, however, can create its own challenges, because many students generally want more flexibility in their schedules and think they should be assessed on what they learn—not how often they show up. A student columnist at the University of Washington expressed frustration at receiving a 20 percent weighted participation grade, which the professor graded based on exit tickets students submitted at the end of class.

“Our grades should be based on our understanding of the material, not whether or not we were in the room,” Sophie Sanjani wrote in The Daily, UW’s student paper.

Most Popular

Keenan Hartert, a biology professor at Minnesota State University, Mankato, set out to understand the factors affecting students’ performance in his own course and found that attendance was one of the strongest predictors of their success.

His finding wasn’t an aha moment, but reaffirmed his position that attendance is an early indicator of GPA and class community building. The challenge, he said, is how to apply such principles to an increasingly diverse student body, many of whom juggle work, caregiving responsibilities and their own personal struggles.

“We definitely have different students than the ones I went to school with,” Hartert said. “We do try to be the most flexible, because we have a lot of students that have a lot of other things going on that they can’t tell us. We want to be there for them.”

It’s not uncommon for a student to miss class for illness or an outside conflict, but higher rates of absence among college students in recent years are giving professors pause.

An analysis of 1.1 million students across 22 major research institutions found that the number of hours students have spent attending class, discussion sections and labs declined dramatically from the 2018–19 academic year to 2022–23, according to the Student Experience in the Research University (SERU) Consortium.

More than 30 percent of students who attended community college in person skipped class sometimes in the past year, a 2023 study found; 4 percent said they skipped class often or very often.

Students say they opt out of class for a variety of reasons, including lack of motivation, competing priorities and external challenges. A professor at Colorado State University surveyed 175 of his students in 2023 and found that 37 percent said they regularly did not attend class because of physical illness, mental health concerns, a lack of interest or engagement, or simply because it wasn’t a requirement.

A 2024 survey from Trellis Strategies found that 15 percent of students missed class sometimes due to a lack of reliable transportation. Among working students, one in four said they regularly missed class due to conflicts with their work schedule.

High rates of anxiety and depression among college students may also impact their attendance. More than half of 817 students surveyed by Harmony Healthcare IT in 2024 said they’d skipped class due to mental health struggles; one-third of respondents indicated they’d failed a test because of negative mental health.

Editors' Picks

MSU Mankato’s Hartert collected data on about 250 students who enrolled in his 200-level genetics course over several semesters.

Using an end-of-term survey, class activities and his own grade book information, Hartert collected data measuring student stress, hours slept, hours worked, number of office hours attended, class attendance and quiz grades, among other metrics.

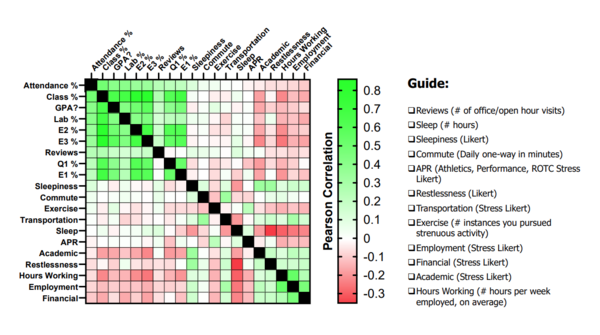

Mapping out the various factors, Hartert’s case study modeled other findings in student success literature: a high number of hours worked correlated negatively with the student’s course grade, while attendance in class and at review sessions correlated positively with academic outcomes.

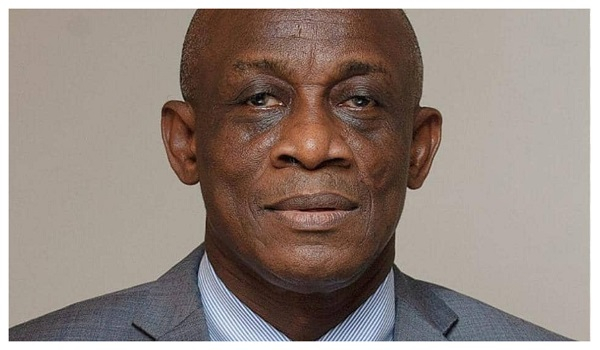

Keenan Hartert

The data also revealed to Hartert some of the challenges students face while enrolled. “It was brutal to see how many students [were working full-time]. Just seeing how many were [working] over 20 [hours] and how many were over 30 or 40, it was different.”

Nationally, two-thirds of college students work for pay while enrolled, and 43 percent of employed students work full-time, according to fall 2024 data from Trellis Strategies.

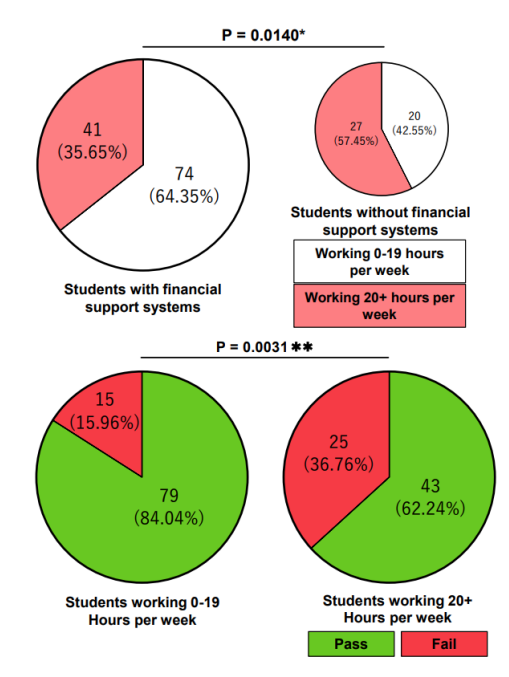

Hartert also asked students if they had any financial resources to support them in case of emergency; 28 percent said they had no fallback. Of those students, 90 percent were working more than 20 hours per week.

Data analysis of student surveys show students who are working are less likely to have financial resources to support them in an emergency.

Keenan Hartert

The findings illustrated to him the challenges many students face in managing their job shifts while trying to meet attendance requirements.

A Faculty Aside

While some faculty may be less interested in using predictive analytics for their own classes, Hartert found tracking factors like how often a student attends office hours was beneficial to helping him achieve his own career goals, because he could include those measurements in his tenure review.

A less measured factor in the attendance debate is not a student’s own learning, but the classroom environment they contribute to. Hartert framed it as students motivating their peers unknowingly. “The people that you may not know that sit around you and see you, if you’re gone, they may think, ‘Well, they gave up, why should I keep trying?’ Even if they’ve never spoken to you.”

One professor at the University of Oregon found that peer engagement positively correlated with academic outcomes. Raghuveer Parthasarathy restructured his general education physics course to promote engagement by creating an “active zone,” or a designated seating area in the classroom where students sat if they wanted to participate in class discussions and other active learning conversations.

Compared to other sections of the course, the class was more engaged across the board, even among those who didn’t opt to sit in the participation zone. Additionally, students who sat in the active zone were more likely to earn higher grades on exams and in the course over all.

Attending class can also create connections between students and professors, something students say they want and expect.

A May 2024 student survey by Inside Higher Ed and Generation Lab found that 35 percent of respondents think their academic success would be most improved by professors getting to know them better. In a separate question, 55 percent of respondents said they think professors are at least partly responsible for becoming a mentor.

The SERU Consortium found student respondents in 2023 were less likely to say a professor knew or had learned their name compared to their peers in 2013. Students were also less confident that they knew a professor well enough to ask for a letter of recommendation for a job or graduate school.

“You have to show up to class then, so I know who you are,” Hartert said.

To encourage attendance, Hartert employs active learning methods such as creative writing or case studies, which help demonstrate the value of class participation. His favorite is a jury scenario, in which students put their medical expertise into practice with criminal cases. “I really try and get them in some gray-area stuff and remind them, just because it’s a big textbook doesn’t mean that you can’t have some creative, fun ideas,” Hartert said.

For those who can’t make it, all of Hartert’s lectures are recorded and available online to watch later. Recording lectures, he said, “was a really hard bridge to cross, post-COVID. I was like, ‘Nobody’s going to show up.’ But every time I looked at the data [for] who was looking at the recording, it’s all my top students.” That was reason enough for him to leave the recordings available as additional practice and resources.

Students who can’t make an in-person class session can receive attendance credit by sending Hartert their notes and answers to any questions asked live during the class, proving they watched the recording.

Hartert has also made adjustments to how he uses class time to create more avenues for working students to engage. His genetics course includes a three-hour lab section, which rarely lasts the full time, Hartert said. Now, the final hour of the lab is a dedicated review session facilitated by peer leaders, who use practice questions Hartert designed. Initial data shows working students who stayed for the review section of labs were more likely to perform better on their exams.

“The good news is when it works out, like when we can make some adjustments, then we can figure our way through,” Hartert said. “But the reality of life is that time marches on and things happen, and you gotta choose a couple priorities.”

Do you have an academic intervention that might help others improve student success? Tell us about it.