For many, Daniel Craig arrived fully formed in a tuxedo, brooding in the shadows of Casino Royale like a beautifully damaged weapon. But Craig’s magnetism—angular, haunted, quietly queer-coded long before Queer (2024)—has been developing since the 1980s, where he honed his edges in British theater and a string of unsung film performances. His appeal has always been split between severity and softness, the charisma of someone who never quite seems comfortable in the spotlight but is electrifying in its glare. Before he became Bond, Craig played dreamers, drifters, psychopaths, and romantics—roles that asked for more vulnerability than violence.

There’s something thrilling about watching an actor before the mythology hardens around them. This list isn’t just a collection of Craig’s lesser-known work; it’s a shadow biography told through character studies and career pivots. These are the films where you see his range open up like a fracture, where he stretches toward something fragile, unknowable, or completely unhinged. In a world of carefully managed movie stars, Daniel Craig remains someone who has always seemed a little dangerous—not because he’s holding a gun, but because he might actually be feeling something.

The Mother

- November 14, 2003

- 112 minutes

- Roger Michell

- Hanif Kureishi

- Angus Finney, David M. Thompson, Kevin Loader, Stephen Evans

Daniel Craig’s performance in is the kind of thing that gets memory-holed once a franchise hardens your jawline into IP. In Roger Michell’s raw and unsettling domestic drama, Craig plays Darren, a working-class handyman who begins an affair with the mother of his much-younger girlfriend—a premise that feels like it should be lurid, but instead unfolds with aching restraint. Anne Reid is astonishing in the title role, and Craig matches her with a performance full of tension, sex, and self-hatred. Before Bond, Craig was already playing men torn apart by desire and class guilt.

What’s remarkable about The Mother is how delicately it treats its characters’ loneliness without excusing their betrayals. Craig’s Darren is fragile, charismatic, and clearly terrified of his own gentleness—the kind of man who’s only soft in moments he can’t control. There’s a scene where he confesses he’s scared of himself, and you believe him. That confession, delivered without melodrama, shows the early bones of Craig’s ability to complicate masculinity: a man who doesn’t speak much, but feels far too much.

This little-seen Irish period drama pairs Craig with Greta Scacchi in a story of doomed love that begins as a pastoral romance and curdles slowly into psychological horror. Craig plays James Lynchehaun, a real-life figure whose obsessive relationship with his employer escalates into brutality. It’s a role that’s hard to imagine another actor attempting without leaning too far into either charm or monstrosity—but Craig plays the whole spectrum, switching between tenderness and rage with terrifying ease.

is not just a love story gone wrong—it’s a portrait of colonial masculinity unraveling. The film’s mood is damp and bitter, and Craig fits into it like he was born in that gray light. He’s magnetic even when he’s repulsive, showing early signs of his talent for making audiences complicit in their desire for dangerous men. It’s one of the first films where you get the sense Craig is pulling something out of the soil—rage, lust, cruelty—and offering it to the camera without apology.

Enduring Love

- November 26, 2004

- 100 minutes

- Roger Michell

- Joe Penhall

- Cameron McCracken, François Ivernel, Kevin Loader, Tessa Ross

In , Craig plays a man shaken by a freak tragedy—witnessing a man fall to his death during a hot-air balloon accident—and then stalked by another witness, played by Rhys Ifans, in a psychological spiral that drifts between grief, guilt, and obsession. The film, based on Ian McEwan’s novel, begins with one of the most quietly terrifying sequences in British cinema and only tightens from there. It’s a story about randomness, about how one moment can puncture the illusion of safety, and Craig carries that trauma like a man slowly being hollowed out.

What’s so compelling here is how unadorned Craig allows himself to be. This is not action-hero pain; it’s existential fragility. His character, Joe, is a rationalist, a lecturer, someone who thinks the world can be solved through logic—and watching that crumble feels eerily prescient of the kinds of male unravellings we now see everywhere onscreen. Craig gives Joe’s terror a physicality: he winces, he shuts down, he refuses comfort. It’s a haunted performance, and a reminder that even before Bond, Craig specialized in men who fall apart gracefully.

Some Voices

- August 25, 2000

- 101 minutes

- Simon Cellan Jones

- Joe Penhall

- Damian Jones, Fiona Morham

Set in a pre-gentrified West London that still feels bruised from Thatcherism, is a small, luminous film that lets Craig do what he’s rarely allowed to in blockbuster mode: disappear into someone who might never be okay again. He plays Ray, a schizophrenic man recently released from a psychiatric hospital, trying to reconnect with the world—and with his brother, played by David Morrissey. The film floats between moments of gentle humor and quiet despair, lit with a dreamy palette that mirrors Ray’s unpredictable interiority. It’s a romance, too—Ray falls for a woman named Laura—but it never lets the viewer believe love will cure him.

What makes Craig extraordinary here is his restraint. Ray isn’t manic or tragic in the usual ways that films so often portray mental illness; he’s just trying. And Craig gives him this hovering lightness, like his mind might float off mid-sentence. There are scenes where his body becomes language—shuffling, twitching, folding in—and others where he’s still, watching the world with a kind of wary awe. This is Craig at his most vulnerable, unprotected by narrative logic or masculine armor, giving a performance that lingers because it never insists on being profound.

Flashbacks of a Fool

- June 5, 2008

- 110

- Baillie Walsh

- Baillie Walsh

This film feels like someone tried to write a dream about being Daniel Craig—fame, regret, buried adolescence—but made it weird and elliptical and sad enough to work. Craig plays Joe Scott, a washed-up Hollywood actor spiraling into substance abuse and self-loathing, whose return to his English seaside hometown unearths old wounds and an unfinished love story. The narrative unfolds like a hangover: hazy, fragmentary, somehow too loud and too quiet at once. It didn’t land with critics, but that may have been the point—this isn’t a comeback film, it’s an elegy.

At its core, is a study of the versions of ourselves we abandon, and Craig is fearless in playing Joe as someone who knows he’s not worth rooting for. What’s most moving is the long central flashback, where a teenage Joe falls in love—set to Roxy Music’s “If There Is Something”—and we see, for a moment, the beauty of who he might have been. Craig’s performance holds that tension: the adult Joe is hollowed out, but you can still glimpse the echo of youth inside him. It’s an imperfect film, but one that gives Craig space to be poetic, broken, and finally human.

Related

Jason Statham's Failed TV Follow-Up to Layer Cake, Explained

Viva La Madness was supposed to be the big Netflix limited series that follows up Layer Cake, and Statham put his own money into it.

Before Casino Royale turned him into the thinking person’s action hero, Layer Cake handed Craig a loaded weapon and a tangled conscience. As an unnamed drug dealer trying to retire from the business cleanly, Craig plays a man who believes in systems—rules, order, quiet exits—and slowly realizes he’s in a world that feeds on chaos. Directed by Matthew Vaughn with hyper-stylized precision, the film is slick but not soulless, violent but calculated. Craig doesn’t swagger; he strategizes.

This is Craig as a man still negotiating power—smart, icy, watching everything. What makes his performance so compelling is the quiet twitch beneath the surface: the dawning understanding that intelligence might not save him. Unlike Bond, this character has no license to kill, just a fragile sense of control, and Craig plays the unraveling beautifully. There’s a moment near the end, gun in hand, where he looks more tired than triumphant. Layer Cake is stylish and cool, yes—but Craig’s performance gives it weight. It’s the role that proved he didn’t need the Bond branding to command a screen. He just needed the silence between lines.

Infamous

- October 13, 2006

- 110 minutes

- Douglas McGrath

- Anne Walker-McBay, Christine Vachon, John Wells

It’s impossible to talk about without acknowledging the shadow of Capote—released the year prior and widely heralded for Philip Seymour Hoffman’s Oscar-winning performance. But Infamous deserves its own lane, and Daniel Craig is a big reason why. In this quieter, more emotionally charged take on Truman Capote’s relationship with murderer Perry Smith, Craig steps into the latter’s shoes and strips away the familiar hardened exterior. His Perry is soulful, volatile, and unnervingly seductive—like a man aware of the myth he’s becoming, and determined to control the narrative.

Craig doesn’t just brood; he lets Smith’s contradictions unfold slowly: a man capable of brutal violence, but also of immense vulnerability. His chemistry with Toby Jones’ Capote is devastating, particularly in a late scene where the lines between intimacy and manipulation collapse entirely. If Capote is about discipline and control, Infamous lets itself bleed a little—and Craig’s performance is the incision point. He gives the kind of presence that lingers in your chest, not because it’s loud, but because it whispers something unresolvable.

Related

Before Bond, Daniel Craig Starred in This Underseen World War I Drama With Cillian Murphy

Daniel Craig may be best known for his role as the cunning spy James Bond, but viewers should also check out his underrated war film.

Set during the 48 hours leading up to the Battle of the Somme, compresses World War I into something both intimate and claustrophobic. Directed by William Boyd, it’s more of a psychological chamber piece than a war film, and Craig plays Sergeant Winter—harsh, deeply tired, and straddling the line between surrogate father and military functionary. The film is grim by design, unfolding entirely within the damp walls of a trench, and Craig’s presence brings the weight of leadership without glorifying it.

What’s haunting about Craig’s work here is how clearly he communicates dread—not through speeches or theatrics, but through glances, posture, silence. This is leadership as slow emotional erosion. There’s a scene where he tries to calm the young soldiers before they go over the top, and you see in his eyes that he doesn’t believe a word of what he’s saying. It’s one of Craig’s earliest showcases of his power in stillness—his ability to make doubt, fear, and resignation flicker beneath a hardened exterior. A quiet film, but not a forgettable one.

Related

Netflix's 'Narnia' Adaptation Looking to Make First Major Casting...and His Word Is His Bond

Following the suggestion that Charlie XCX could be heading to Narnia as the White Witch, it looks like Netflix has its magician in its sights.

Too easily dismissed as Oscar bait with a grenade launcher, deserves a second look—not just as a rare World War II film centered on Jewish resistance, but as a deeply physical performance from Craig. He plays Tuvia Bielski, the leader of a partisan group hiding in the Belarusian forests and protecting hundreds of Jewish refugees. What could have been a one-note tale of heroism instead becomes a nuanced story about ethical compromise, brotherhood, and the weight of survival.

Craig brings a rough, grounded dignity to Tuvia, not as a mythic figure, but as a man constantly at odds with the violence he must commit. He spends much of the film either silent or shouting—there’s not a lot of in-between—and both extremes feel earned. What makes the performance stand out is how much it rejects triumphalism. Craig plays Tuvia as exhausted, grief-stricken, and fiercely protective, not of his legacy, but of the people in front of him. It’s one of the few action-oriented roles where his strength comes from the refusal to glorify violence—and that makes it rare.

On paper, should’ve been a moody, prestige thriller: a haunted-man psychological puzzle starring Daniel Craig and Rachel Weisz, directed by Jim Sheridan. But the film was re-cut by the studio, marketing gave away its major twist, and critics panned it on arrival. Yet within the fractured structure and uneven tone lies a performance from Craig that’s surprisingly tender and emotionally raw. He plays Will Atenton, a man who moves his family into a country home only to slowly unravel a deeper, more tragic truth.

The twist—widely spoiled, yet still worth experiencing—isn’t what makes Dream House interesting. It’s Craig’s navigation of the thin line between love and delusion, between memory and fantasy. He’s unusually exposed here: we see him grieve, hallucinate, doubt himself, fall apart. The film may not fully cohere, but Craig’s presence grounds it. He gives a genre story a layer of real emotional ache, as if he’s playing not a man in a thriller, but someone trying to survive the unbearable architecture of loss.

The fourth remake of Invasion of the Body Snatchers came with major baggage—studio interference, a second director brought in for reshoots, and a critical reception that called it both flat and unnecessary. But rewatch it now, and The Invasion feels oddly prescient. Craig plays a doctor who aids Nicole Kidman’s CDC psychiatrist as a strange, empathy-erasing epidemic spreads across Washington D.C. It’s sleek and sterile, but there’s something eerie in how it captures a society sliding into calm, enforced compliance.

Craig’s role isn’t showy, but that’s what makes it work. He plays the straight man to Kidman’s growing dread, the last human pulse in a world going numb. There’s a quiet chemistry between them that underlines what the film is trying to say: that emotional messiness—love, anger, pain—is the last thing that makes us human. The Invasion isn’t perfect, but it’s quietly unnerving, and Craig’s cool steadiness gives the film a center of gravity it desperately needs. In a world of body doubles and placid smiles, he still flinches.

Related

Every Invasion of the Body Snatchers Movie and How Each is an Allegory For Their Time

The Invasion of the Body Snatchers is one of the most prolific stories in all of horror. Let's look at each movie to find the allegory for their time.

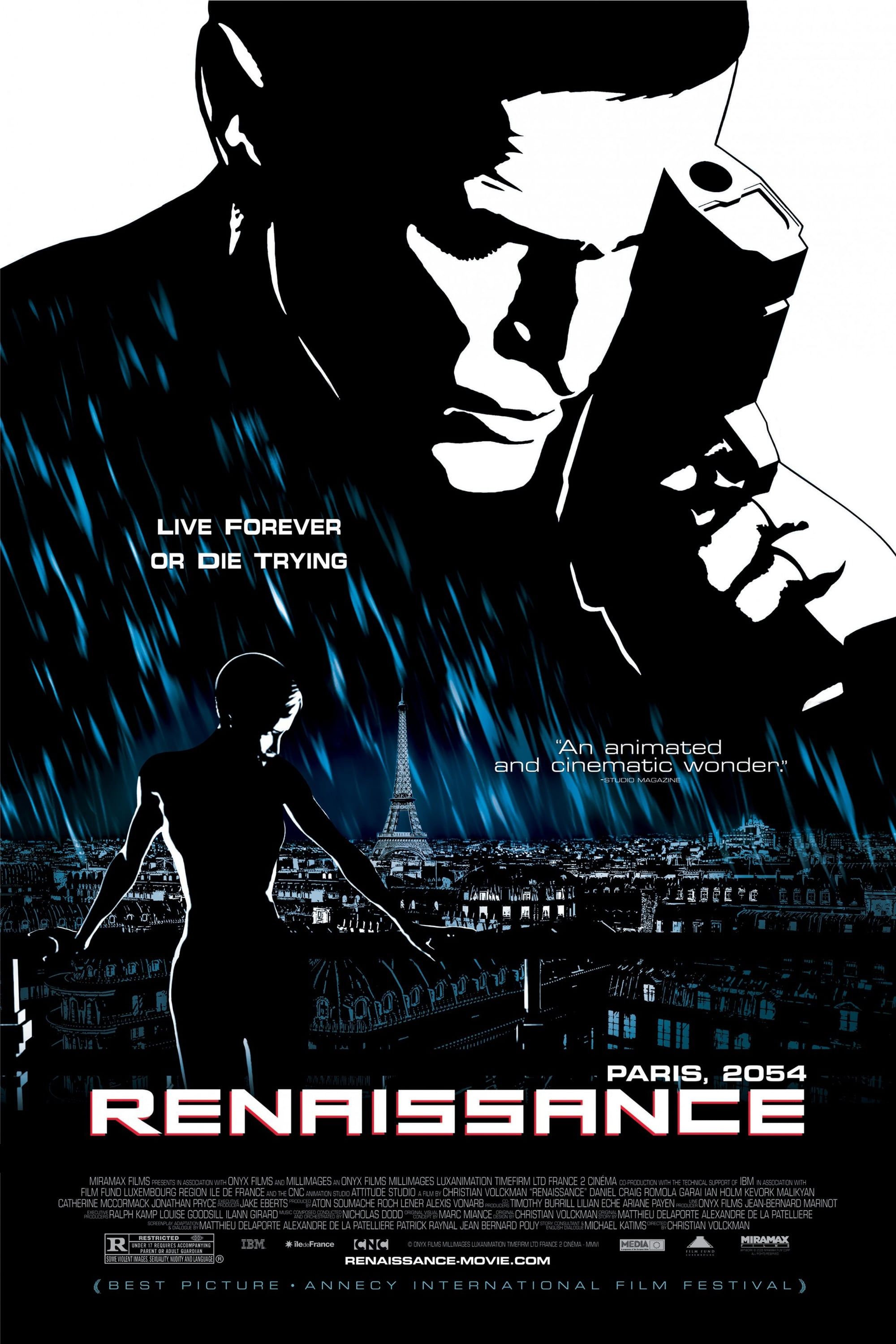

renaissance

- March 16, 2006

- 105

- Christian Volckman

- Alexandre de La Patellière, Mathieu Delaporte, Michael Katims, Jean-Bernard Pouy, Patrick Raynal

An animated French noir with rotoscope-style black-and-white visuals so stark they feel carved in chrome, is less a film than a fever dream of corporate dystopia. Set in a hyper-surveilled Paris of 2054, the story follows a detective unraveling the disappearance of a scientist tied to a powerful biotech company. Craig voices the lead, Barthélémy Karas, with a gravelly restraint that makes the film’s cold aesthetic feel even more chilling. It’s Sin City meets Blade Runner, if both films were dipped in ink and drained of light.

This is Craig not as a face but as a texture: his voice carries weight, exhaustion, and latent violence. In a film where human expressions are often abstracted, Craig’s performance becomes strangely grounding. He gives Karas not just noir grit, but the sense of someone always watching the clock, trying to outrun the system. Renaissance isn’t warm or easy—it’s dense and often emotionally remote—but Craig’s voice cuts through like static on a clean signal. It’s one of the few times we get to experience his persona stripped to pure tone.

Obsession

- August 28, 1997

- 105 minutes

- Peter Sehr

- Marie Noëlle

- Dagmar Rosenbauer, George Hoffmann, Martine Kelly, Rainer Mockert, Wolfgang Esterer

Almost no one talks about , partly because it barely had a release and partly because it’s a strange hybrid of erotic thriller and psychological mystery that doesn’t quite land—but it holds a fascinating early Craig performance. He plays John MacHale, a man tangled in a fatal attraction storyline set against the brooding backdrop of 1990s rural Scotland. The plot veers from melodrama to psychodrama, but Craig brings a kind of dangerous calm to the center—a man you trust just enough to regret it.

What’s fascinating here is how Craig experiments with ambiguity. He’s not yet refined, not yet mythologized, and Obsession lets us watch him lean into that messy, pre-fame mode. His presence is magnetic but raw, a little unpredictable, like someone figuring out where to put the weight in a sentence. The film itself is flawed and oddly paced, but Craig’s performance—simmering, withheld, just slightly off-center—is a glimpse of the darker edges he’d later sharpen into steel.

This might be the most purely delightful Daniel Craig performance ever captured on screen. As Joe Bang, a bleach-blond, egg-loving explosives expert helping two brothers rob a NASCAR race, Craig is all twitch and charm, like someone who got electrocuted in a Waffle House bathroom and came out enlightened. , Steven Soderbergh’s Southern-fried heist film, thrives on its own weird wavelength, and Craig syncs to it perfectly, gleefully dismantling his Bond persona one scene at a time.

Craig’s comedic timing here is impeccable—not in a punchline way, but in how he uses silence, drawl, and stillness to punctuate the absurdity around him. Joe Bang is a character who’s both in on the joke and completely sincere, and Craig plays him with a kind of giddy reverence. This is a man who has nothing to prove anymore, which makes the performance all the more freeing. If Casino Royale introduced us to the modern action man, Logan Lucky is where that man finally learned how to laugh.