BMC Medical Ethics volume 26, Article number: 81 (2025) Cite this article

Research involving vulnerable populations of people living with HIV (PLWH), such as children, adolescents, older adults, pregnant and lactating women, hospitalized patients, and key populations, presents complex bioethical challenges. We assessed bioethics training needs for trainees engaged in HIV research from the School of Medicine (SoM) of Makerere University and the Infectious Disease Institute (IDI) to inform the development of a comprehensive bioethics training program for trainees.

A cross-sectional quantitative study was conducted from March to May 2024 using an online structured questionnaire distributed via Google Forms. Participants included former and current trainees who have conducted research with PLWH within the past five years. Data collected included self-rated bioethics knowledge, frequency of encountering bioethical challenges, confidence in addressing challenges across vulnerable populations, and preferred training topics and delivery formats. Descriptive data analysis was performed using STATA Version 17.

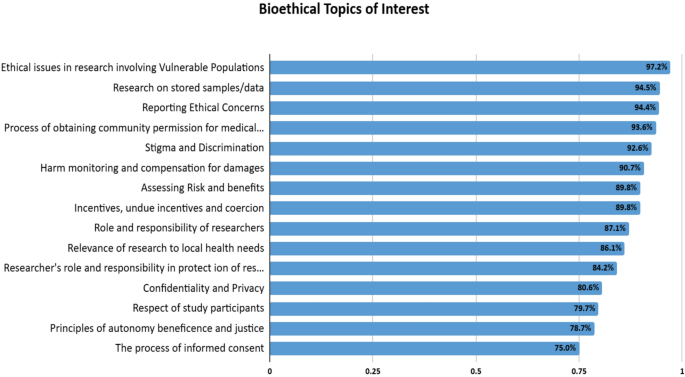

We attained a response rate of 67.5% (108/160). While 75.9% reported formal bioethics training, 58.3% rated their knowledge moderate. Frequently encountered challenges included maintaining confidentiality and privacy (61.1%), conducting informed consent processes (56.1%), applying bioethical principles, engaging with communities (54.6%), and selecting appropriate research participants (51.4%). Confidence in addressing bioethical challenges was notably lower for vulnerable populations than for general HIV research. Confidence of the trainees was higher in research involving older PLWH and pregnant/lactating women, moderate with children/adolescents and hospitalized individuals, and very low with key populations. Trainees expressed limited confidence in addressing cultural sensitivity, stigma, coercion, community engagement, harm monitoring, and compensation for research-related harm across all the populations. Top training priorities included ethical issues with research involving vulnerable populations (97.2%), reporting ethical concerns (94.4%), community engagement (93.6%), research on stored samples/data (94.5%), and stigma/discrimination (92.6%). Preferred formats were in-person workshops, interactive case-based scenarios, and online courses.

Trainees faced diverse bioethical challenges and exhibited varying confidence levels in addressing these issues across different vulnerable populations. These findings underscore the need for targeted, context-specific bioethics training tailored to conducting research with vulnerable PLWH. This study has informed the development of a comprehensive training program to improve the ethical conduct of HIV research in Uganda.

Not applicable.

Research involving vulnerable populations of people living with HIV (PLWH) in resource-limited settings (RLS) poses unique and complex bioethical challenges [1, 2]. Vulnerable populations include children, adolescents, pregnant and lactating women, older adults, hospitalized patients, and key populations, usually identified as sex workers, gay, bisexuals, and other men who have sex with men (GBMSM), transgender individuals, and people who inject drugs (PWID) [3, 4]. These groups often face compounded vulnerabilities due to stigma, discrimination, and legal and social marginalization, necessitating tailored ethical considerations to safeguard their rights and well-being [2, 5,6,7]. In developing countries, vulnerabilities are further exacerbated by factors such as low literacy, limited access to healthcare, and socioeconomic disparities, where individuals may agree to participate in research without fully understanding its implications or in hopes of accessing otherwise unavailable resources [4]. The stigmatization and criminalization faced by some of these vulnerable populations, in many SSA settings, poses bioethical challenges during the design and implementation of studies intended to expand coverage of prevention strategies, increase treatment uptake, and improve retention in care [6, 8,9,10,11].

Research involving human participants is often required for graduate students in academic Sub-Saharan institutions. At Makerere University, College of Health Sciences, trainees frequently conduct research involving PLWH. However, the current curriculum lacks structured bioethics training tailored to the unique challenges of research with vulnerable populations of PLWH. Although foundational frameworks like Good Clinical Practice (GCP) and Human Subjects Protection (HSP) offer basic ethical guidance, they fail to address the complex, nuanced issues trainees face during research implementation. This gap leaves trainees underprepared, potentially leading to inconsistent ethical practices and challenges in safeguarding participants’ rights during research [12,13,14,15,16]. Many faculty members also lack formal training in research ethics, compromising their ability to supervise student research effectively [17]. These deficiencies underscore the urgent need for targeted training to navigate the ethical complexities of research involving vulnerable populations.

We assessed the bioethics training needs of master and PhD trainees engaged in HIV research at Makerere University, College of Health Sciences- School of Medicine and the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI). The purpose was to inform the development of a robust, context-specific bioethics training program to better prepare trainees for ethical research practices among vulnerable populations of PLWH in Uganda.

We conducted a descriptive cross-sectional quantitative survey between March and May 2024 to assess bioethics training needs among trainees at the School of Medicine (SoM) and the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI), both under the College of Health Sciences at Makerere University. SoM trains a large cohort of graduate students across various clinical and public health disciplines, many of whom engage in research involving people living with HIV (PLWH) as part of their academic programs. In contrast, IDI is a specialized research institute affiliated with Makerere University, recognized as a center of excellence in HIV care, treatment, and research. All IDI trainees are directly involved in HIV-related research projects. Including trainees from both institutions enabled a comprehensive assessment of bioethics training needs among a diverse group of individuals actively engaged in clinical HIV research across academic and clinical environments.

We employed two main strategies to identify eligible participants from the School of Medicine (SoM) and the Infectious Diseases Institute (IDI). First, we obtained lists of current and former trainees from both institutions, which included names, contact information, and dissertation titles. We reviewed departmental graduation lists since 2019. This process yielded a total of 630 trainee contacts—546 from SoM and 84 from IDI. We then screened dissertation titles to identify those related to HIV research, resulting in 160 eligible participants. To supplement and verify HIV research involvement, we conducted an independent search of the Makerere University Institutional Repository, where all students are required to upload their dissertations.

To confirm eligibility, we conducted an independent search of the Makerere University Institutional Repository (Mak-IR), where all student dissertations are archived. At IDI, all trainees were automatically eligible since their training is exclusively HIV-focused. Inclusion criteria were: [1] current or former postgraduate trainees at SoM or IDI between 2019 and 2024, and [2] documented involvement in HIV-related research, demonstrated by defended proposals, archived dissertations in Mak-IR, or departmental confirmation of ongoing HIV research. Exclusion criteria included trainees who had been formally terminated by either institution for academic or disciplinary reasons.

Only eligible trainees (N = 160) were contacted via email and followed up with telephone contact to inform and request their participation in the study. The survey was administered online using Google Forms. A survey link was sent to each participants’ email integrated with an electronic informed consent form that provided comprehensive information about the study.

We developed a new structured, questionnaire informed by review of literature on ethical issues HIV research incorporating key themes relevant to working with vulnerable populations. For each population, we used a 16-item checklist of key bioethical issues that were identified through literature review [1, 9, 18,19,20,21]. The tool was piloted with 20 participants with similar characteristics to the target study population who provided feedback on item clarity, relevance, and comprehensiveness. Minor revisions were made based on pilot feedback, including rewording of ambiguous items and refining response scales to enhance usability and comprehension. Reliability testing of the pilot responses showed strong internal consistency of the survey tool, with a Cronbach’s alpha of 0.98. We collected data on demographic characteristics (age, education background, sex, affiliated institution, HIV research experience, and primary vulnerable population focus), self-rated knowledge of bioethics in HIV research, frequency and confidence in addressing bioethical challenge in addressing bioethical challenges across five vulnerable populations (children & adolescents, older adults, pregnant and lactating women, hospitalized patients, and key/sensitive populations). Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale. We also assessed training needs and preferences through preselected topics and participant-suggested recommendations.

To minimize missing data, we configured the survey tool to require responses to all questions before submission. To enhance the response rate, weekly email and telephone reminders were sent throughout the study.

Survey data were exported to STATA Version 17 for analysis. Descriptive statistics were used to summarize participants’ demographic characteristics, self-rated knowledge of bioethics, frequency of encountering bioethical challenges, and confidence in addressing these challenges. Categorical variables were summarized using frequencies and percentages. To explore subgroup differences, we conducted chi-square (χ²) tests of independence to examine variations in participants’ confidence in addressing selected bioethical challenges across five vulnerable populations.

For analytical clarity and to simplify reporting, the original 5-point Likert scale was collapsed into a 3-point scale. “Very confident” and “Confident” responses were combined into a single “confident” category, while “not confident” and “not confident at all” were grouped under “not confident.” The “neutral” category was retained. This approach was deemed appropriate given the exploratory nature of the study and the need to identify broad training needs rather than capture fine-grained distinctions. This decision is consistent with recommended survey practices, particularly in contexts where response distributions are skewed or where collapsing improves cell size and interpretability [22]. We acknowledge that this transformation may have reduced the granularity of the data, potentially limiting the ability to detect subtle variations in confidence levels. This has been noted as a study limitation.

To assess differences in participants’ confidence in addressing bioethical challenges across the vulnerable populations, we conducted subgroup comparisons using Chi-square tests of independence. For each of the 16 bioethical challenge items, confidence levels were compared across the population groups. A p-value of < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Of 160 participants contacted, 108 (67.5%) responded to the survey. The majority (61%) were former trainees, 57% were men, and most (96.2%) were aged 25–45 years and held a master’s degree (86.1%) (Table 1).

The most frequently encountered bioethical challenges reported by participants were maintaining confidentiality and privacy (61.1%), conducting the process of informed consent/assent (56.1%), applying bioethical principles such as autonomy, beneficence, and justice (54.6%), community engagement (54.6%), determining the relevance of research to local health needs (53.7%) and appropriate selection of research participants (51.4%). The less frequently encountered challenges included issues related to stigma and discrimination (45.8%), reporting ethical concerns (33.4%), incentives, undue inducement, coercion (32.7%), and harm monitoring and compensation for damages (22.5%). (Table 2)

In conducting general HIV research, participants reported high confidence in conducting the informed consent process (91.7%), maintaining confidentiality and privacy (93.5%), applying bioethical principles (82.4%), and fulfilling the role and responsibility of researchers in protecting participants (82.4%). However, confidence was notably lower in addressing challenges related to stigma and discrimination (58.3%), reporting ethical concerns (58.3%), community engagement (58.3%), understanding the role of regulatory frameworks (53.7%), assessing risk and benefits (46.3%), harm monitoring and compensation for damages (46.3%), and cultural sensitivity (46.3%). (Table 2)

Despite the high confidence levels observed for general HIV research, there was a significant drop and variation in confidence levels across all bioethical challenges among vulnerable populations. Higher confidence was observed in contexts involving older PLWH, pregnant/lactating women, moderate confidence for children/adolescents and hospitalized individuals, and very low confidence for key populations (< 55%). Challenges such as maintaining confidentiality and privacy and applying principles of autonomy, beneficence, and justice) were areas of higher confidence (73-85%) for older PLWH and pregnant/lactating women. Lower confidence (29–44%) was reported for addressing cultural sensitivity, stigma and discrimination, and harm monitoring and compensation for damages for key populations. Confidence was moderate (60-70%) for issues such as reporting ethical concerns, assessing risk and benefits, and ensuring appropriate participant selection across all populations, highlighting specific areas requiring targeted training and capacity building, particularly when engaging with key populations and hospitalized patients (Table 3). Statistically significant differences (p < 0.05) were observed in most areas, except for research on stored samples/data (p = 0.150), where confidence levels were similar across groups (Table 3).

In-person workshops were the preferred (60.1%) modality of training, followed by online courses (53.7%) and interactive case-based discussions (46.3%). Participants showed strong interest in a wide range of bioethics topics for inclusion in the curriculum, with the highest levels of interest reported for ethical issues in research involving vulnerable populations (97.2%), reporting ethical concerns (94.4%), community engagement in research (93.6%), and stigma and discrimination (92.6%). Topics such as research on stored samples/data (94.5%), harm monitoring and compensation for damages (90.7%), and assessing risk and benefits (89.8%) also garnered significant interest. While other areas had lower preferences, they still reflected a substantial interest (75% and above). (Fig. 1).

Participants suggested several additional topics for inclusion in the bioethics curriculum, including ethical considerations in clinical trials for HIV care, the role of research ethics committees, community engagement in sensitive populations, multi-sectoral collaboration, and addressing ethical dilemmas in special circumstances (e.g., unconscious patients, notifiable diseases), genetic research ethics, paternal consent in pregnant women, data sharing, material transfer processes, post-trial access, and conduct of research in emergency settings. Specific issues regarding the GBMSM and transgender-related research were highlighted, specifically safeguarding human participants while adhering to legal frameworks and addressing data protection.

This study assessed the bioethics training needs for trainees and junior researchers conducting research with PLWH. The findings revealed that trainees commonly faced various bioethical challenges, such as maintaining confidentiality and privacy, conducting informed consent processes, applying bioethical principles, engaging with communities, and selecting appropriate research participants. While trainees reported high confidence in addressing bioethical challenges in research with PLWH, their confidence levels were significantly lower and varied with different vulnerable populations, particularly key populations.

The bioethical principles referenced—autonomy, beneficence, and justice—are drawn from the foundational Belmont Report [23]. Although non-maleficence is considered a distinct principle in other frameworks [24], in this study it is conceptually integrated within beneficence, consistent with established interpretations in bioethics literature. This reflects the view that beneficence entails both the obligation to promote good and to avoid harm. For detailed definitions of each principle, see Table 4.

Although previous studies have explored the perceptions, knowledge, attitudes, and practice of trainees in medical and research ethics [17, 25,26,27,28], to the best of our knowledge, this is the first study focusing on vulnerable populations with or at risk of acquiring HIV in a country with a high HIV prevalence.

Despite the frequent engagement of trainees in research involving vulnerable populations significant gaps in bioethics training, knowledge and confidence in addressing complex ethical challenges, especially when working with key and marginalized populations were identified. This calls for an urgent need for targeted, context-specific training to strengthen ethical competence in conducting research among vulnerable groups.

While a significant majority of trainees reported having received some formal bioethics training and frequently encountering ethical challenges, their confidence was only moderate suggesting that the current training at Makerere University lacks contextual relevance, and practical application needed to address complex ethical challenges with vulnerable populations.

Higher confidence was reported in obtaining informed consent and maintaining confidentiality, however, confidence dropped for less frequent challenges, such as addressing stigma and discrimination, cultural sensitivity, harm monitoring and compensation, and reporting ethical concerns.

Participants reported high confidence in conducting research with older PLWH and pregnant/lactating women which may reflect more established ethical guidelines and experience in these areas. Lower confidence was reported for children and adolescents, key populations, and hospitalized patients. Conducting research with these groups may pose unique ethical challenges. For example, research with children and adolescents requires obtaining parental consent and participants’ assent, and potential additional risks [29,30,31], while conducting research with sick and hospitalized patients presents unique challenges such as the determination of decision capacity, involvement of surrogate decision makers, risk versus benefit assessments, patient vulnerabilities, community engagement, and regulation of research [32, 33]. There is limited context-specific guidance on how to practically navigate these challenges [7].

In addition to the identified challenges, recent literature also suggests that some negative attitudes toward PLWH may stem not only from stigma or sociocultural biases, but also from perceptions of cognitive impairment. Neurocognitive challenges such as memory loss, reduced attention span, and executive dysfunction are particularly prevalent among some older PLWH and may hinder communication or informed consent processes [34,35,36]. When combined with lower literacy and socioeconomic disparities, these factors can reinforce implicit bias among healthcare workers or researchers, leading to exclusion or insufficient support for affected individuals. This highlights the importance of ethical training that incorporates an understanding of HIV-associated neurocognitive disorders, cultural sensitivity, and communication strategies to mitigate potential discrimination and uphold participant autonomy [35].

Of note research with key populations in Uganda and other African settings faces instead unique challenges, as persons and behaviors of GBMSM in many settings in SSA are highly stigmatized and even illegal [8, 10, 37] resulting in bioethical challenges when designing and implementing research studies. In Uganda a recent area of concern is the recently signed Anti-Homosexuality Act (AHA) which criminalizes same-sex behavior and may have a detrimental effect on research in HIV prevention, access to HIV testing and service delivery for key populations [38]. Also, a recent study [8] recommended a major focus on cultural sensitivity, community engagement, and reflexivity in research design and implementation for research among certain key populations in Uganda.

To situate our findings in a broader context, similar concerns about ethical preparedness have been reported in other cultural settings [34, 39], where studies among healthcare professionals and students emphasize the need for strong, context-specific ethical training. Recent literature further underscores the value of extending bioethics training beyond healthcare professionals to include patients and family members, especially in HIV research where stigma, cultural beliefs, and cognitive or literacy-related barriers may influence participation and ethical conduct [40, 41]. Involving these broader stakeholder groups can enhance ethical sensitivity, reduce stigma, and promote more inclusive and responsive research practices. Our study addresses this gap by identifying the tailored ethical training needs of trainees in HIV research withinSub-Saharan Africa. Future efforts should consider expanding training to engage patients, families, and communities as active partners in ethical research conduct.

For future bioethics training, in-person workshops emerged as the most favored training modality, followed by online courses and interactive case-based discussions. Participants expressed strong interest in a broad range of topics including those they had earlier on expressed confidence in addressing, reporting ethical concerns, community engagement in research, research on stored samples/data, harm monitoring and compensation, and risk-benefit assessment. Participants also suggested incorporating other topics such as genetic research ethics, ethical considerations in clinical trials for HIV care, paternal consent for pregnant women, data sharing, material transfer processes, and post-trial access.

We had a high non-response rate of 32.5%. However, since the online survey was distributed to all individuals of interest and the response rate was adequate (generally considered as at least 60% [42], the opinions of the trainees surveyed likely represent the ones of our population of interest [43]. Additionally, the reliance on a purely online survey introduced potential biases, as responses were subjective to participants’ understanding of vulnerable populations and other bioethical concepts. Self-reported data is also inherently prone to recall bias and social desirability bias [44].

In conclusion, the findings highlight that trainees demonstrate a lack of confidence in addressing various bioethical challenges in research involving vulnerable populations of people living with HIV (PLWH), despite their frequent engagement in such research. These findings are likely generalizable to similar academic and research institutions in East Africa that train students in HIV research, with potential applicability across sub-Saharan Africa. The insights gained have informed the development of a short bioethics training curriculum tailored to HIV research among vulnerable populations or those at risk of acquiring HIV. This training will target trainees and junior investigators at Makerere University, utilizing a mixed approach that includes lectures, real-world case scenarios, and prospective mentorship.

This study’s strengths include a strong response rate, a systematic survey design, and a focus on an important yet underexplored area of HIV research ethics. However, the study had limitations, including potential biases from self-reported data and social desirability, varying interpretations of key terms, and the treatment of key populations as a homogeneous group rather than as distinct subgroups. Additionally, collapsing Likert-scale categories may have reduced the granularity of responses. While the list of bioethical issues covered was broad, it was not exhaustive, and some ethical dimensions may have been overlooked. Despite these limitations, the study provides a solid foundation for developing context-specific bioethics training in HIV research among vulnerable populations, and informing future research in similar settings.

All data supporting the findings of this study are available within the paper and its Supplementary Information.

- IDI:

-

Infectious diseases institute

- SoM:

-

School of medicine

- PLWH:

-

People living with HIV

- RLS:

-

Resource limited settings

- GBMSM:

-

Gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men

- GCP:

-

Good clinical practice

- HSP:

-

Human subject protection

- REC:

-

Research ethics committee

- HIV:

-

Human immunodeficiency virus

- UNCST:

-

Uganda national council of science and technology

- Mak-IR:

-

Makerere university institutional repository

We acknowledge Ms. Flavia Dhikusooka, Mr. Joseph Musaazi, and Ms. Patience Nantume for their contribution in developing the online survey.

This Research was supported by the Fogarty International Center of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number D43TW009771. The content is solely the authors’ responsibility and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

This study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki. Ethical approval was obtained from the Infectious Diseases Research and Ethics Committee (reference number: #REF IDI-REC 2023-078), and from Uganda National Council for Science and Technology (UNCST, reference number: HS3771ES). Informed consent was obtained from all participants. Participants received detailed information about the survey through an electronic consent form (as approved by the REC) embedded within the survey link. Those who voluntarily chose to participate indicated their consent by selecting “I agree to participate” before proceeding to the survey. The e-consent served as an acknowledgment of willingness to participate rather than a full signature.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Nayiga, J., Okoboi, S., Banturaki, G. et al. Bioethics training needs assessment for HIV research in vulnerable populations: a survey of trainees at college of health sciences, Makerere university. BMC Med Ethics 26, 81 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-025-01244-y

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12910-025-01244-y