You may also like...

First Look: 2026 NBA All-Star Weekend Unveils Uniform Designs and Preview

The 2026 NBA All-Star Game in Los Angeles will feature new competition formats, including a "Team USA versus The World" ...

Lookman Inspires Atlético's Historic 4-0 Demolition of Barcelona

Atlético Madrid secured a historic 4-0 triumph over Barcelona in the Copa del Rey semi-final first leg, with Nigerian st...

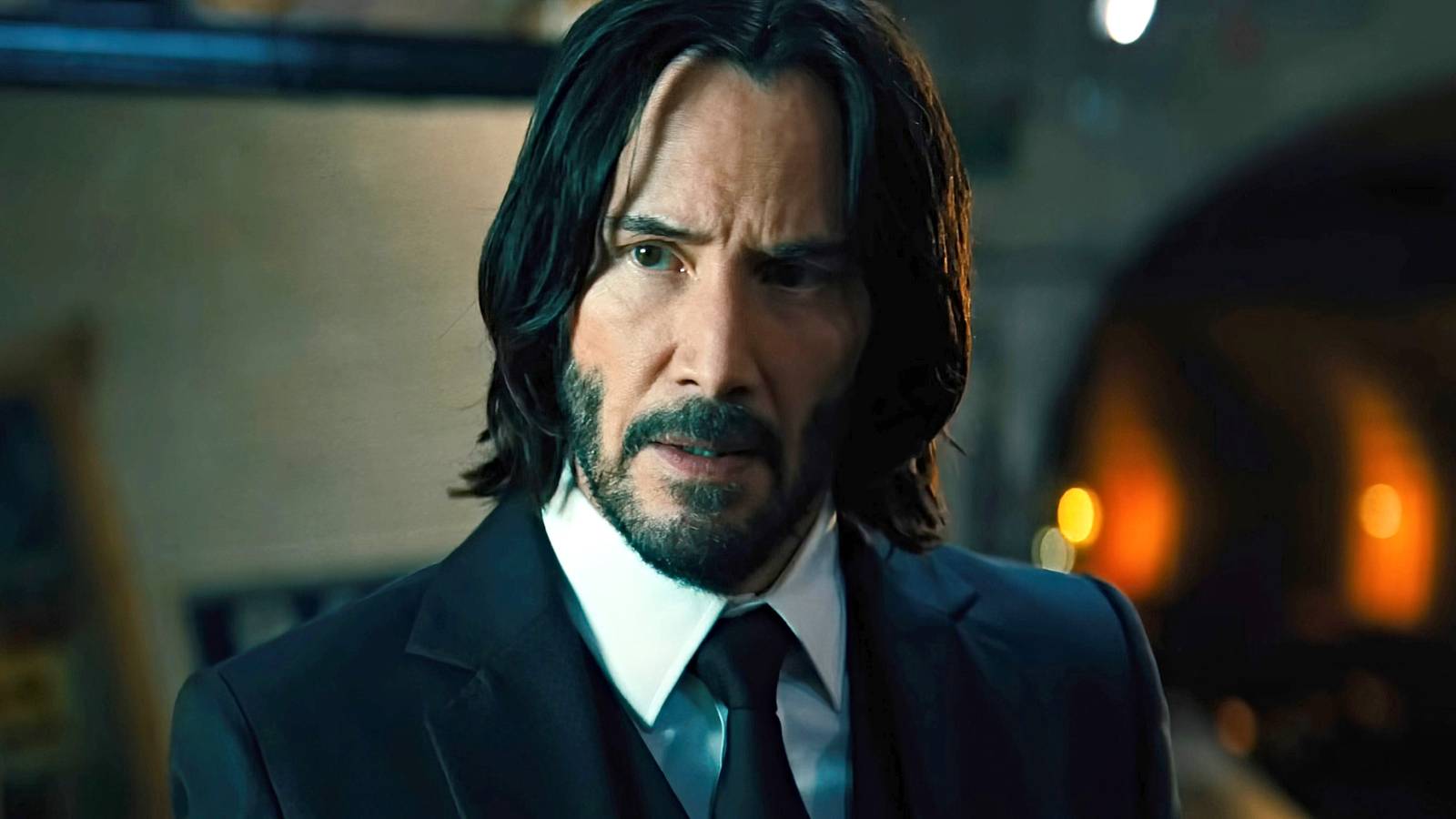

He's Back! Legendary Assassin John Wick Returns After Three-Year Silence!

The highly anticipated 'Untitled John Wick Video Game' has been officially unveiled at PlayStation State of Play, featur...

Netflix Sci-Fi Shocker: Long-Awaited Fate of Boldest Series Unveiled!

Despite solid critical and audience reception, Netflix's animated series "Terminator Zero" has been canceled after only ...

Doja Cat Conquers Africa: Superstar to Headline Global Citizen's Move Afrika Tour

Doja Cat is set to headline Move Afrika in Rwanda and South Africa this March, fulfilling a long-awaited homecoming. The...

The Queen Is Back! Jill Scott Ends 11-Year Album Hiatus with 'To Whom This May Concern'

Jill Scott makes a grand return with her sixth studio album, "To Whom This May Concern," her first in over a decade. The...

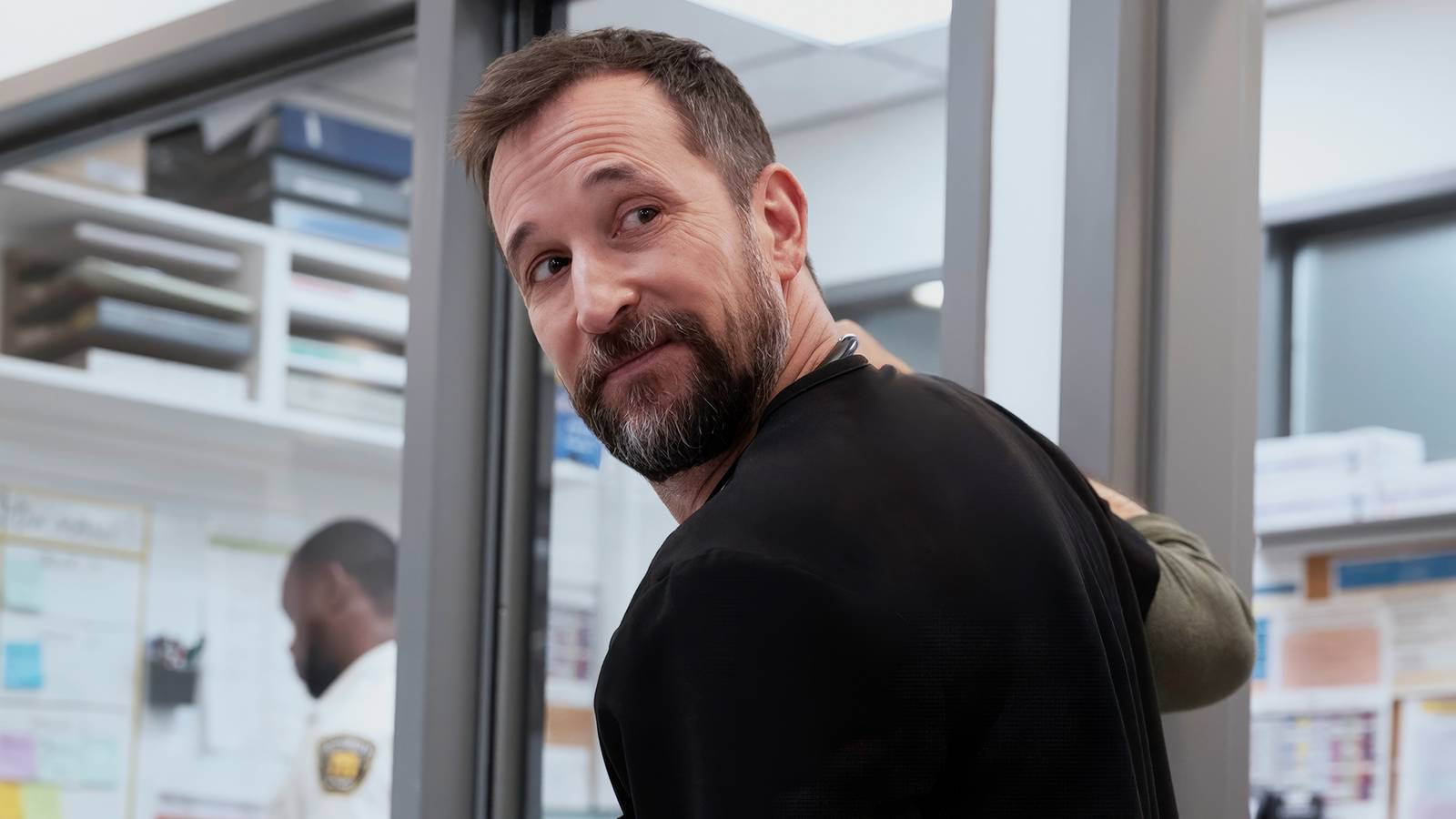

Inside 'The Pitt': Noah Wyle's 'Funeral With a Clock' Episode Unpacked by Shaken Cast

HBO's "The Pitt" Season 2, Episode 6, "12:00 P.M.," plunges the Pittsburgh Trauma Medical Center into chaos with a "Code...

Talent Retention Secrets Revealed: Ayobami Esther Akinnagbe on Keeping Top Employees

Retaining top talent is crucial for organizational success, yet high employee turnover remains a significant challenge. ...