5 facts you may not know about Ofili's switch of allegiance

The success stories of African athletes who switched allegiance at the 2024 Paris Olympics have continued to spark heated debate among sports aficionados.

From Kenyan-born Bahrain’s Winfred Yavi, winner of the 3,000m women’s steeplechase and new Olympic record holder, to Nigeria’s Annette Nneka Echikunwoke, who bagged silver for her birth country, the USA, having previously represented Nigeria in the hammer throw, the number of athletes switching allegiance to Arab nations continues to rise at an alarming rate.

Annette would have featured for Nigeria at the Tokyo Olympics until the usual show of shame and negligence on the part of Nigerian officials reared its ugly head after the International Olympic Committee (IOC) banned Annette and nine other Nigerian athletes from participating due to the AFN’s failure to conduct mandatory tests.

Nigerians woke up last weekend to the shocking news of Favour Ofili’s switch of allegiance to Turkey. With personal bests of 10.93 seconds in the 100m and 21.96 seconds in the 200m, the 22-year-old sprinter was tipped to be the next big thing in track and field, given her talents and insatiable hunger to reach the zenith of her sport. The NOC’s blunder ensured that she missed out on the Tokyo Olympics after her name was not on the list of competing athletes.

Thunder struck twice and Ofili reached her tipping point at the 2024 Paris Olympics, where her name was mysteriously absent from the start list for the 100m, despite meeting the qualifying standard. This unfortunate situation was attributed to a familiar issue in Nigeria: a failure in paperwork. Now that she will likely be competing in all-red Turkish colours at the next World Championship in Tokyo, here are five facts you may not know about Ofili’s switch of allegiance:

One of the major factors behind Favour Ofili’s switch of allegiance to Turkey is the financial incentives that come with it. In a country where medal hopefuls fight to get \$100 as daily camp allowance at the Olympics and World Championships, it is only a matter of time before they switch loyalty to nations who are ready to splash the cash.

Findings revealed that some athletes were paid N10,000 while others earned N50,000 at the National Trials for the African Senior Athletics Championships in Douala and the Paris 2024 Olympics held in Benin City, Edo State, 2024, while officials smiled to the bank with their pockets lined with dollars. It is that bad.

Ofili is expected to earn $500,000 as a sign-on fee, monthly support, kit endorsement and access to an exclusive training centre as a Turkish athlete. Turkey splashed $500,000 on each gold medal won at the 2024 Paris Olympics and it is likely to increase at the next Olympics. Also, Kazakhstan, which includes former Kenyan runners in its team for Paris, offered a gold medal bonus of $250,000 compared to Kenya, where gold medal winners at the 2020 Tokyo Olympics earned a bonus of about $8,000.

The Nigerian sports authorities have a penchant for not providing adequate kits for athletes at major events. More often than not, most athletes get just one running vest, one tracksuit, and sometimes no shoes at all to compete for Nigeria at global meets, while officials run sports shops. It has become a norm for Nigerian athletes to resort to washing their running vests and tracksuits like their counterparts in national football teams.

These nations offer better training facilities, coaching, and medical support compared to Nigeria, where a cyclist famously borrowed a bike from the German team during the 2024 Olympics.

But Ofili will focus on the medals and not lose sleep over kits, knowing full well that Turkey and global kit companies will dole out cash each time she steps out in the Turkish national running vest.

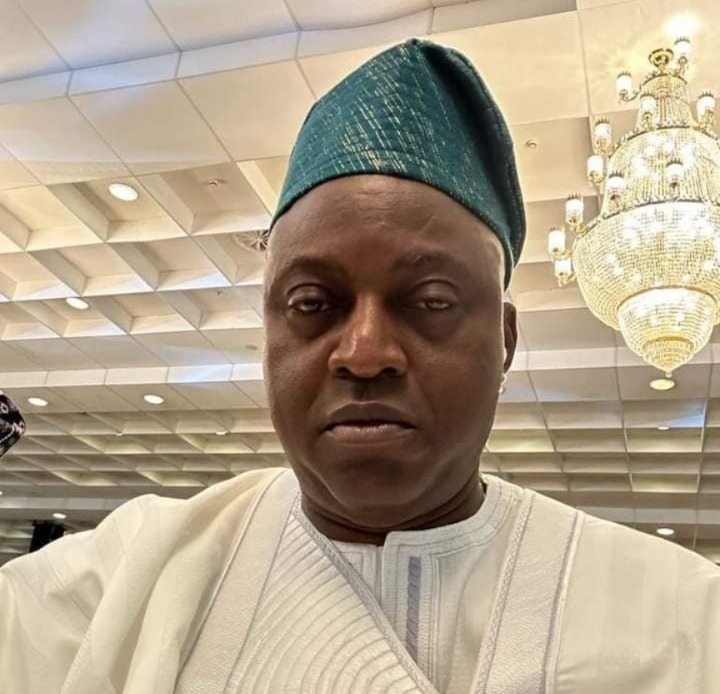

A reliable source revealed to The Guardian that Ofili is faced with the psychological fear of missing out on another major championship after her last two unpleasant experiences in Tokyo and Paris. The Owan Enoh investigation committee was a mere charade, and expectedly, the unseen hands behind Ofili’s omission at the Paris Olympics are still walking free. She felt whoever did that to her was still on the board and saw that as a loud warning siren. She then packed her kits and headed to where she would be valued.

The Nigerian Sports Ministry pays athletes between \$5,000 and \$10,000 as training grants; a far cry from what nations like Bahrain, Qatar, Oman, and Turkey offer their upcoming athletes. Besides, these grants—which cannot get an athlete to the podium—are either delayed or never paid at all in most cases, thereby forcing athletes to spend their hard-earned resources to use top facilities abroad and pay coaches.

The Nigerian Athletics Federation is filled with glory-turned-to-ashes tales of athletes who hardly receive training grants from Nigerian authorities.

For athletes like Ofili, who face intense competition for Nigeria’s limited international slots, switching to a less competitive country can provide greater global exposure. Additionally, personal factors such as marriage or dual citizenship may also influence these decisions; however, Ofili’s specific reasons remain undisclosed.

Ofili won’t be the last because the switching of nationalities has been happening for years, and unless African countries provide improved conditions for athletes to succeed at home, it will continue.

While Ofili’s decision once again proves that talent and patriotism are not always enough to maintain loyalty, her decision also carries potential risks. Athletes who switched allegiance hardly enjoy lasting prominence abroad in their post-retirement years. Daniel Ighali, despite winning gold in wrestling for Canada, returned to Nigeria to serve as president of Nigeria’s Wrestling Federation. Gloria Alozie won gold for Spain at the 2002 European Championships after switching allegiance and also returned to coach a new generation of athletes.

The reason for this is not far-fetched: most countries that poach athletes value foreign-born competitors only during their competitive years, but offer little cultural or social integration after retirement.