What is humidity? Here's what causes this hot and sticky phenomenon | National Geographic

The first major heat wave of summer has enveloped much of the midwestern and eastern U.S. in a brutal “dome” of record temperatures and high humidity. The dome phenomenon happens when weather conditions cause high pressure to remain stagnant, trapping bands of heat and humidity within a region for long periods of time.

Experts warn that heat-related illness, including heat exhaustion and heat stroke, pose significant risks over the coming days.

It’s no surprise that summer’s high temperatures bring with them oppressively high humidity, but what causes these muggy conditions and why does they make us feel so much hotter?

Humidity happens when water vapor in the atmosphere enters the air through the evaporation of water at the surface. When the temperatures rise in the summer months, more water evaporates than in the winter months when it’s colder outside.

“The greater amount of water vapor in the atmosphere, the more humid it is,” says James Marshall Shepherd, director of the University of Georgia's Atmospheric Sciences Program.

In regions of the country that are generally wetter, like the eastern U.S., there’s more water on the surface to evaporate, resulting in more humidity. Summertime weather patterns out of the gulf region caused by warm water temperatures and prevailing wind patterns lead to an additional flow of moisture coming from the south that can add to steamy conditions.

When your body heats up, a region of the brain called the hypothalamus sends a signal to your sweat glands that it’s time to cool down. Sweating is the body’s primary mechanism for reducing its internal temperature. When you sweat, your body evaporates water from your skin, absorbing energy in the process and thereby reducing heat.

Sweating is the body's primary method for regulating heat and can be less effective when humidity levels are too high.

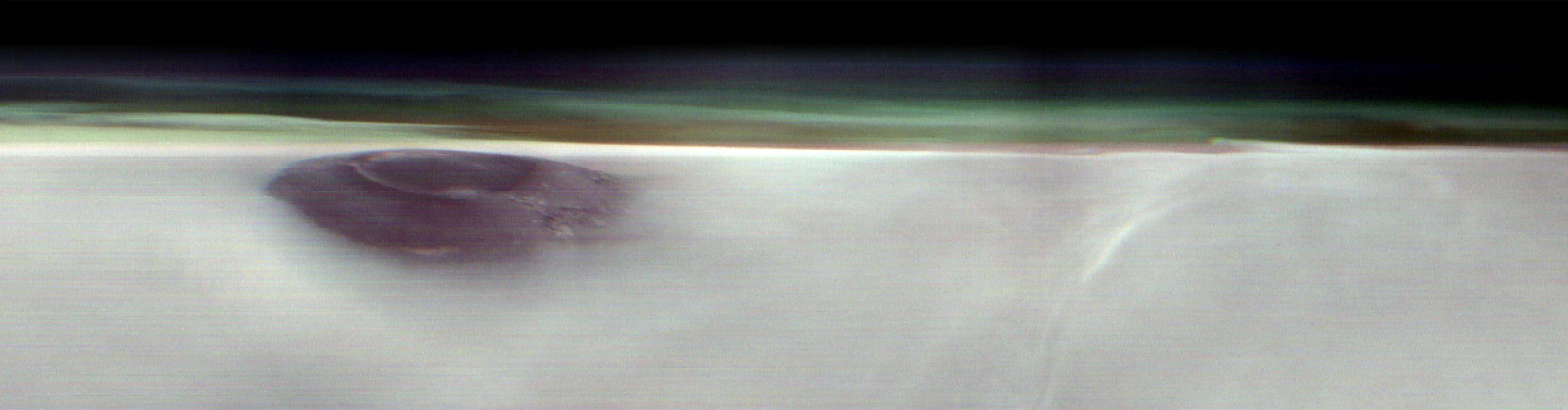

Illustration by Asklepios Medical Atlas, Science Source

“The amount of water that can be evaporated from your skin depends on how much water vapor is already in the air,” says Mary D. Lemcke-Stampone, the New Hampshire State climatologist and an associate professor of geography at the University of New Hampshire.

With high humidity comes higher relative humidity: the ratio of how much water vapor is in the air compared to how much water vapor the air can hold before reaching condensation and precipitation.

Too much water vapor or humidity in the air means there’s no room for sweat to evaporate from your skin. In other words, you might sweat, but the sweat doesn’t have anywhere to go. In dry heat conditions like the desert, on the other hand, your body doesn’t feel as hot because evaporation takes the water—and as a result, heat—off the skin’s surface.

The term “wet bulb effect” or “wet bulb temperature” refers to how effectively the body can cool down in high heat and high humidity conditions. Specifically, it’s the lowest your body temperature can go as a result of sweating.

When heat and humidity are too high, humans can’t properly cool themselves. This causes the body to overheat, which can lead to heat exhaustion and heat stroke. Around 95°F combined with high humidity is considered the limit for human survival, but even much lower temperatures of 88°F can be dangerous.

“When you’re not cooling off as fast, then you’re going to feel those symptoms of heat stress more than if your body was able to cool through its normal mechanisms,” says Lemcke-Stampone. Some of these symptoms include fatigue and nausea.

The amount of water the air holds depends on its temperature, and as air warms, its relative humidity drops. Experts contend that the climate is changing and the atmosphere is on average getting warmer, resulting in an increase in humidity.

A February 2025 study found that over the last 40 years, humid heat waves have increased in severity, especially across the eastern U.S., amplifying heat waves and increasingly putting people at risk. Additionally, the higher the heat, the more water is evaporated from lakes, streams, and other bodies of water, which adds more humidity to the air.

Still, one of the most insidious aspects of a high humidity heat wave is that the heat doesn’t break at night, especially in cities which are covered in asphalt and concrete that trap warmth instead of absorbing it. Heat swells in urban areas, radiating into the night and building on itself the next day.

So even though the temperature may be a bit lower in the evening, the body doesn’t get a respite from the heat, says Allegra N. LeGrande, a climate scientist at the NASA Goddard Institute for Space Studies & Center for Climate Systems Research.

“High nighttime temperatures are absolutely a facet of climate change,” says LeGrande.

As humidity gets worse, it comes with the added risk of over exposure. High heat means that many of us will need to have a plan in place when the weather becomes extreme.

Relying on air conditioning may not be enough. Be prepared by staying hydrated, and keeping ice and fans on hand, which increase windspeed around your body and help reduce your internal temperature, says LeGrande. A cold shower can help to cool your body down in a pinch because water traveling through underground pipes will be cooler than water on the surface, such as in pools and lakes.

Know beforehand where your city’s cooling centers are in case you don’t have air conditioning, it stops working, or your area’s electrical grid reaches capacity and the power goes out.

It’s not just society’s most vulnerable, like the elderly and those with chronic conditions, who are at risk for heat-related illnesses. New research shows that younger people are increasingly being stretched to their physical limits due to the heat, potentially because they’re more likely to work outdoors in these temperatures.

“Make sure you’re checking in with friends, family, and neighbors—even those who you might not expect to be impacted,” says LeGrande.