Watch List 2025 - Spring Update (22 May 2025) - World | ReliefWeb

Each year, Crisis Group publishes two updates to the EU Watch List identifying where the EU and its member states can enhance prospects for peace. This update covers Armenia-Azerbaijan tensions, drug trafficking from Latin America, Pakistan’s forcible expulsion of Afghan refugees, the Sahel and Syria.

Introduction

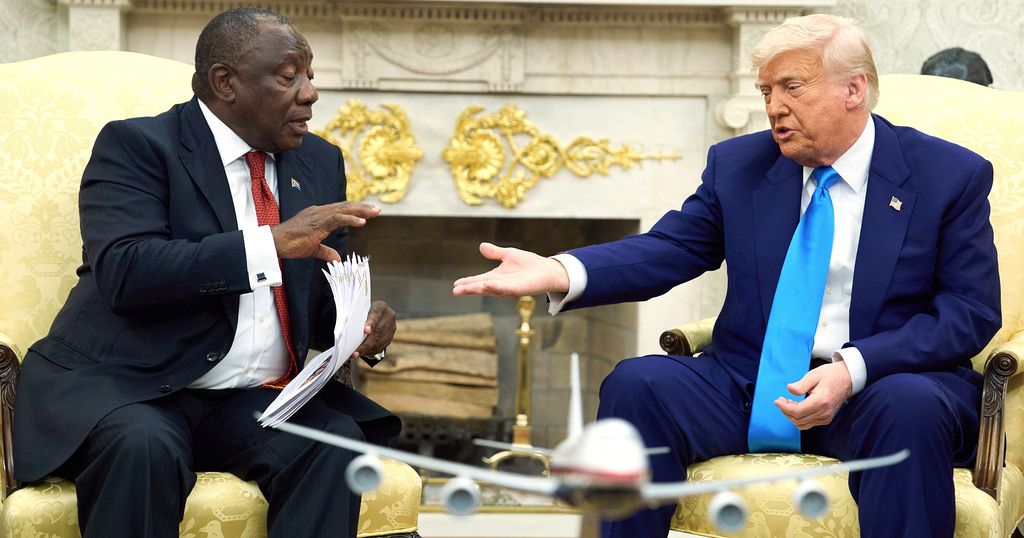

For the European Union and its member states, a long-deferred moment of reckoning has arrived with Donald Trump’s re-election to the U.S. presidency.

Some European leaders may have been lulled into complacency by Trump’s first term. After all, when he sat in the White House from 2017 to 2021, Trump was more bark than bite. He made clear his frustration both with the EU, which he saw as undercutting the U.S. economically, and the NATO alliance, which he viewed as free-riding on Washington’s military might. But though Trump and his emissaries made these views known in uncomfortable meetings with European counterparts, his first administration did little to turn them into concrete policy – often because senior officials checked the president’s impulses.

This time is different. The administration has been constructed on the basis of loyalty to Trump and is more serious about realising the president’s preferences. It is also cannier about the mechanics of doing so. At the core of those preferences is a desire to free the U.S. from traditional relationships that Trump sees as expensive and entangling, the work of a foreign policy elite he despises. In place of the old alliances, he wishes to pursue a transactional approach to international relations. He wants the U.S. to use its enormous political, military and economic clout to secure deals that, in his view, will help “Make America Great Again” by dint of their benefits to the U.S. citizenry. In all likelihood, the president envisions that some close to him will profit, too.

This “America first” foreign policy was on display in Trump’s first major trip abroad in May (save a brief sojourn to Rome for the funeral of Pope Francis), which saw him visit three Gulf monarchies; pocket billions of dollars in investment commitments in exchange for transfers of arms and technology; and deliver a scathing speech attacking the interventionist inclinations of prior administrations.

There may be certain upsides to Trump’s approach. The unqualified support Trump enjoys from allies throughout the U.S. government gives his administration space to do unorthodox things that predecessors would have quailed from. He has, for example, been ready to disregard the predilections of hawks in Washington and Israel when it comes to many elements of Middle East policy: engaging in several rounds of nuclear talks with Iran, pulling back from a campaign that his own administration escalated against Houthi insurgents in Yemen, speaking directly with Hamas and lifting U.S. sanctions on Syria that have been strangling the country’s economic recovery (though as yet he has done nothing to stop Israel’s horrific assault on Gaza).

From the perspective of Washington’s European allies, however, Trump’s iconoclasm has mainly had downsides. Indeed, in its turbulent first three months, the new administration compromised virtually every dimension of traditional trans-Atlantic cooperation. With respect to matters of principle, Trump’s embrace of territorial expansionism – including the intimation that he might seize Greenland from NATO ally Denmark by force – marked the U.S. as a revisionist power, ready to redraw borders at will. If the U.S. and EU used to coordinate efforts to meet development and humanitarian challenges around the world, Trump’s dismantling of the U.S. Agency for International Development upended that tradition, leaving huge gaps in global aid budgets. The EU and member states are scrambling to fill some of these holes, while making clear that their finances will not allow for plugging them all. Then came the U.S. tariffs levied on 2 April (“liberation day”, Trump called it), which hit allies hard. (The imposts have since been partially suspended until early July.)

Could things be worse? Yes. Peace and security arrangements are wobbly, but still largely intact. The administration briefly cut off material and intelligence assistance to Ukraine (the former was allocated under President Joe Biden’s administration) following a disastrous meeting between Trump and Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy on 28 February – but that has resumed, at least for the time being. Washington has not walked away from NATO or any of its treaty allies in the Indo-Pacific. After stunning the Munich Security Conference in February with a speech that sounded like an attack on European democracies (and on the same trip lending his support to Germany’s far-right opposition), Vice President JD Vance struck an almost conciliatory tone when he spoke to the forum’s leadership in May.

But for the EU and member states, these remain uncomfortable times. While Trump has yet to repudiate a mutual defence commitment, his apparent disdain for alliances can only call into question whether he would stand behind them in a pinch. Nor is it clear what might happen down the road in terms of U.S. troop deployments in Europe, which U.S. officials have said will be reduced, but not by how much or in exactly which places. European leaders are awaiting the results of a “force posture review” to see whether it becomes the vehicle for a major shift of U.S. troops off the continent. The best outcome would be a phased plan, to be rolled out over a term of years, which gives European powers time to develop their own defences as the U.S. draws down.

Against this backdrop of shocks and challenges, the Ukraine file has been especially difficult for European leaders to manage. As Crisis Group has noted elsewhere, the Trump administration manoeuvred the U.S. into a role that previously would have been unthinkable – acting as a mediator between Russia, on one side, and Ukraine and its mainly European backers, on the other. At times, this approach appeared to clear room for diplomacy, but the prospect of a deal – even a ceasefire – appears increasingly illusory. Russian President Vladimir Putin shows no sign of entertaining the truce that Washington was urging upon the parties and Zelenskyy agreed to accept. Nor, despite Trump’s unconventional diplomacy, does anything thus far suggest that Putin will walk back his oft-repeated goal of stripping Ukraine of its capacity to defend itself or form security relationships with Western capitals. The Russian president refused to travel to Istanbul to negotiate with Zelenskyy on 15 May and stonewalled Trump during a 19 May telephone conversation, which ended without a breakthrough.

That call left Trump suggesting that he would defer to Kyiv and Moscow to work things out between themselves. While the administration has recalibrated its approach to Ukraine more than once over the past three months, Trump’s desire to first get some kind of pause in the fighting and then remove the U.S. from further Russia-Ukraine diplomacy has been a consistent throughline. If the U.S. genuinely steps back from talks, peace-seeking diplomacy with Russia will become vastly more difficult for Ukraine and its European supporters, as Putin has made clear he is mainly, and perhaps only, interested in engaging Trump. Not just that – if Washington takes the further step of again cutting off support to Ukraine, this time for the long run, the EU and member states may struggle to compensate in full. Even with the big strides Ukraine has made in its own weapons production, gaps remain – especially with respect to air defence and intelligence. What Russia is able to achieve in this scenario may partly depend on the extent to which the U.S. remains willing to sell Ukraine and its backers air defence systems and to share intelligence.

Ukraine’s European backers can thus be expected to try to buy time, as they have already been doing with some success. Skilful diplomacy by London, Paris and others has helped Zelenskyy repair bridges with Trump and may even have convinced some in the administration that European leverage can help Washington forge a deal. The natural resources deal Ukraine signed with the U.S. could be read as increasing Washington’s interest in keeping Kyiv sovereign – and perhaps offering some justification for continuing to provide it with support – though the agreement is, in fact, thin on commitments. French President Emmanuel Macron and British Prime Minister Keir Starmer have also been at the forefront of a coalition of Ukraine’s supporters that has advanced discussions about a “reassurance force” that could – hypothetically – be deployed to Ukraine in the event of a ceasefire. Even if doubts about the viability of such a force persist, the planning demonstrates to both Moscow and Washington that Europeans are willing to step up. Still, the EU and member states must live with the possibility that Trump’s patience will run out, perhaps even abruptly, and they will be left with an enormous responsibility that will be onerous to meet.

While the EU and member states should have done more to make themselves less dependent on Washington before President Trump’s return, there is no longer any hiding from the challenge. Though the administration seems to have eased up on its European allies for now, Trump has clearly signalled that, more than any other U.S. president of the post-World War II period, he sees trans-Atlantic ties as expendable. There is no stable ground on which to rest the trans-Atlantic relationship that does not involve Europe exercising greater autonomy. But the continent remains too dependent on the U.S. militarily and economically to move in that direction as quickly as might be optimal. European leaders will need to work to keep the U.S. as committed as possible to Ukraine and NATO, for as long as possible, while also preparing for the possibility that one day, possibly soon, the U.S. assistance – at least in its current form – will be gone. In that case, as Crisis Group has previously written, European governments will need to help Ukraine defend itself, continue backing Kyiv in negotiated efforts to end the war (assuming those continue), and develop new strategies and plans for deterrence that do not rely on U.S. aid, commitments or enablers, such as transport, logistics and intelligence.

In this evolving European security architecture, the EU and member states will not be able to put up a soldier, ship or plane for each one that the U.S. pulls back, but instead will have to look to other options. Already, EU and NATO members are exploring how to use assets they have in a manner that reflects the budgets, threat assessments and risk tolerance of the countries involved. One idea gaining traction would see coalitions of like-minded countries – potentially including countries in NATO but not the EU, like the UK, Türkiye, Norway and Canada – uniting outside EU or NATO auspices to develop plans for defence purchases and other purposes. But with budgets tight and elections looming in several key states, capitals face a challenging set of tasks as they seek ways to invest in their joint security future without undermining immediate needs. NATO’s summit in June at The Hague may provide more of a roadmap, though, given the need to get all allies on board for plans, it will surely also leave much unanswered.

Beyond managing their own security, there is ample room for the EU and member states to carve out greater autonomy from the U.S. in setting their course vis-à-vis the rest of the world. Amid Trump’s unpredictability, Brussels is working to project itself as a reliable partner to a range of regional powers with whom deepened relations could provide economic, political or security benefits. In the first few months of 2025, the EU’s leadership had high-level engagements with India, Türkiye and South Africa, for example. In the second-to-last week of May, a long-awaited EU-African Union ministerial meeting is taking place in Brussels. Around the same time, the EU and the UK held a post-Brexit summit in London, to unveil a reset deal to improve relations.

Beyond Ukraine, no crisis merits Europe’s attention more than the catastrophe unfolding in Gaza. Nineteen months after Hamas attacked Israel on 7 October 2023, killing nearly 1,200 people and taking 251 hostages, Israel’s war in the strip has evolved into a phase seemingly defined less by the goal of destroying Hamas than by the unmaking of Gaza itself. Under the banner of Operation Gideon’s Chariots – a plan that has military and aid delivery components – Israel has relaunched large-scale airstrikes, while opening fresh axes for ground incursions and razing depopulated neighbourhoods, letting artillery and drones pound the rest. Already, the Israeli army has rendered 70 per cent of the strip a “no-go zone”. The plan is now apparently to funnel civilians through army checkpoints into cramped “humanitarian zones” to receive only ration-level aid. The scheme, by the lights of the UN‐coordinated body that assesses these matters, could tip the entire enclave into famine. With Gaza under total blockade since 2 March, prices for staples have skyrocketed, the entire population faces life-threatening food insecurity and a quarter of the population is starving. With the threat of mass starvation looming, Israel opened Gaza to aid trucks on 19 May, but the UN describes the supplies that have made it into the strip as a “drop in the ocean”. Israeli ministers openly label this new phase as “conquest”, and Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu has made clear that his demand for ending the war includes what Israel calls “voluntary emigration” of Palestinians to third countries – which amounts to engineered depopulation under fire.

Whatever security logic might once have driven the war has evaporated. Israel claims to have eliminated most of Hamas’s senior commanders and weapons. Yet the devastation has pushed many young men into the group’s ranks, according to intelligence assessments. Meanwhile, the Israeli military campaign continues to flatten Gaza’s remaining buildings, destroy its governance capacity and rend its social fabric. Inside Israel, families of those still held by Hamas understand that every fresh assault further imperils the captives’ lives. A majority of Israelis have consistently called for an end to war to release the hostages as well as early elections to replace the Netanyahu government.

Many EU member states have condemned the Gideon’s Chariots plans – including in a joint statement signed by 24 foreign ministers (including seventeen from the EU), European commissioners and the EU high representative, which demanded an immediate, full resumption of aid deliveries through tested existing channels, according to recognised humanitarian norms. France, Canada and the UK also put out a joint letter with similar demands. Such statements are a welcome, if belated, response to one of the worst humanitarian disasters of recent decades.

But gestures will be ineffective unless linked to concrete steps aimed at curbing Israel’s policies. As Israel’s biggest trading partner, the EU should use the review of Israel’s compliance with the human rights provision of the EU-Israel Association Agreement – which EU member states pressed for on 20 May – as leverage, demanding that Israel end the war and allow immediate relief into Gaza in exchange for retaining its trading privileges. States like the UK and Germany should ban weapons sales to Israel until it stops the war and lifts the siege. Other measures might include an expansion of existing sanctions targeting West Bank settlements and individual sanctions against Israeli ministers and officers involved in human rights abuses.

Other crises where the EU and member states can make a positive contribution sit further from the headlines. This EU Watch List update focuses on some of those crises, with entries on Armenia-Azerbaijan peace talks, Afghanistan-Pakistan tensions, the Sahel and Syria, as well as drug trafficking from Latin America to Europe. As always, this list is non-comprehensive. It does not address, for example, the civil war in Sudan, or the gang violence that is consuming Haiti or the conflicts that are tearing at Myanmar’s periphery. Crisis Group has covered these cases elsewhere, including in previous editions of the EU Watch List. But the present list does zero in on a handful of hotspots where the EU and member states can foster stability, serving their security, economic and humanitarian interests, while helping bring more peace to a changing and perilous world.