"Trying not to be seen": a qualitative study exploring adolescent girls experiences seeking antenatal care in a Nairobi informal settlement

“Trying not to be seen”: a qualitative study exploring adolescent girls’ experiences seeking antenatal care in a Nairobi informal settlement

- Correspondence to Ms Anne Achieng; achieng96{at}gmail.com

Adolescent girls living in low-income urban informal settlements face unique challenges that elevate their susceptibility to early childbearing. However, there has been limited research attention, especially qualitative studies, on their use or non-use of antenatal care (ANC) services. Informed by the socioecological theory, we examined the obstacles to and facilitators of ANC services use among pregnant adolescent girls in a low-income urban informal settlement in Kenya.

The study adopted a qualitative explanatory design. We purposively selected 22 adolescent girls aged 13–19 who were either pregnant or had given birth, 10 parents and three health providers to participate in individual interviews. We employed inductive and deductive thematic analyses informed by socioecological theory to explain the barriers to enablers of antenatal services use among pregnant adolescent girls in low-income informal settlements.

Most adolescent girls interviewed faced barriers at multiple socioecological levels, resulting in delayed ANC initiation and fragmented engagement with services. At the intrapersonal level, girls grappled with internalised stigma and late pregnancy recognition and acceptance, often dismissing early signs due to fear or denial. Their young age and limited knowledge of maternal health left them terrified in fear, caught between societal judgement and the daunting prospect of confronting their condition. At the interpersonal level, societal stigma and discrimination pushed many into secrecy, hindering their access to antenatal services. However, parents, other family members, and health providers played a key role in enabling access to care by offering various forms of support to pregnant girls, including offering counselling and accompanying girls to clinics. At the organisational level, user fees and condescending health providers’ attitudes hindered ANC use. Yet, good patient-provider communication, privacy and confidentiality played a key role in enabling ANC attendance.

Pregnant adolescent girls face unique challenges that prevent them from accessing ANC early and completing the recommended number of visits. These challenges range from intrapersonal factors to interpersonal and organisational factors. Programmes to improve early initiation of ANC for pregnant adolescents should include interventions that address the social stigma associated with early and unintended pregnancy, promote family support and make health facilities responsive to the needs of pregnant girls.

Data are available upon reasonable request.

http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/

This is an open access article distributed in accordance with the Creative Commons Attribution Non Commercial (CC BY-NC 4.0) license, which permits others to distribute, remix, adapt, build upon this work non-commercially, and license their derivative works on different terms, provided the original work is properly cited, appropriate credit is given, any changes made indicated, and the use is non-commercial. See: http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc/4.0/.

If you wish to reuse any or all of this article please use the link below which will take you to the Copyright Clearance Center’s RightsLink service. You will be able to get a quick price and instant permission to reuse the content in many different ways.

Globally, the maternal mortality rate for pregnant adolescents aged 15–19 is twice as high as that for young women aged 20–24 years.1 Pregnant adolescents also face a higher risk of obstetric fistula, eclampsia and pre-eclampsia, puerperal endometriosis and systemic infections than young women aged 20–24 years.2 3 Furthermore, babies born to adolescent girls have a higher risk of low birth weight, preterm birth and severe neonatal conditions.4 5 These risks make it vital for pregnant adolescents to seek quality maternal care services.6 Equally important is the need to start antenatal care (ANC) visits early and within the first trimester.7

Early initiation of ANC and completing the WHO-recommended eight ANC visits can facilitate early identification of danger signs, provide opportunities to mitigate complications, and improve birth outcomes.8 ANC attendance can also help health providers offer physiological, biomedical, behavioural, psychological and sociocultural support to pregnant women.8 However, studies have shown that pregnant adolescents are less likely to initiate ANC early or complete the recommended number of visits compared with older women.9 A study in Tanzania found that 70% of adolescents started ANC in their fifth month of pregnancy,10 while a study in Kenya found that only 12% of adolescents attended ANC in their first trimester.11

Several factors, from individual to social to systemic levels, contribute to late initiation and non-use of ANC services among pregnant girls.12 Late recognition of pregnancy and lack of autonomy in decision-making,13 lack of knowledge of ANC services, young age14 and pregnancy denial15 are individual factors found to be associated with ANC use among adolescents. Adolescent girls also tend to hide their pregnancy due to the ramifications that befall them when the pregnancy is disclosed, such as being sent away from school, and the sociocultural norms of the traditional family structure.11 15 16 Adolescents and young girls, and their families, may also face social stigma.17

Studies exploring barriers and enablers of ANC services use among pregnant adolescent girls are mostly quantitative.18 19 Qualitative studies are particularly illuminating because they provide in-depth insights into a phenomenon. Yet, qualitative studies on barriers and enablers of ANC services use among pregnant girls in Kenya are limited. Girls in urban informal settlements face unique challenges that increase their vulnerability to early childbearing, yet their use or non-use of ANC services has received limited research attention. Guided by socioecological theory, we highlighted the barriers to and enablers of ANC services use among pregnant girls in an urban informal settlement. As more and more people reside in low-income urban informal settlements, data are needed to plan and address their needs, including health needs. Our findings can be important to understanding the unique challenges faced by pregnant girls in accessing ANC in informal settlements and could inform policies and programmes to address these challenges.

Socioecological theory is an instrumental framework for understanding the barriers and enablers to accessing ANC among pregnant adolescent girls in low-income informal settlements. This model incorporates individual and contextual health determinants, viewing health as an interaction between individuals, groups, communities and the broader physical, political and social environment.20 21 In this study, we examined intrapersonal factors, which are biological or personal history factors that hinder or enable pregnant adolescent girls from accessing ANC; interpersonal factors, which are relational, community and cultural factors around the adolescent girls’ immediate environment; and organisational factors, which include institutional and policy factors that affect access to ANC services among pregnant adolescent girls.22–24 The model allows for the evaluation of healthcare service provision, efficiency and efficacy. The theory informs the interview guide design and analysis of the data, pointing to the individual, interpersonal and systemic factors influencing ANC use among adolescents.

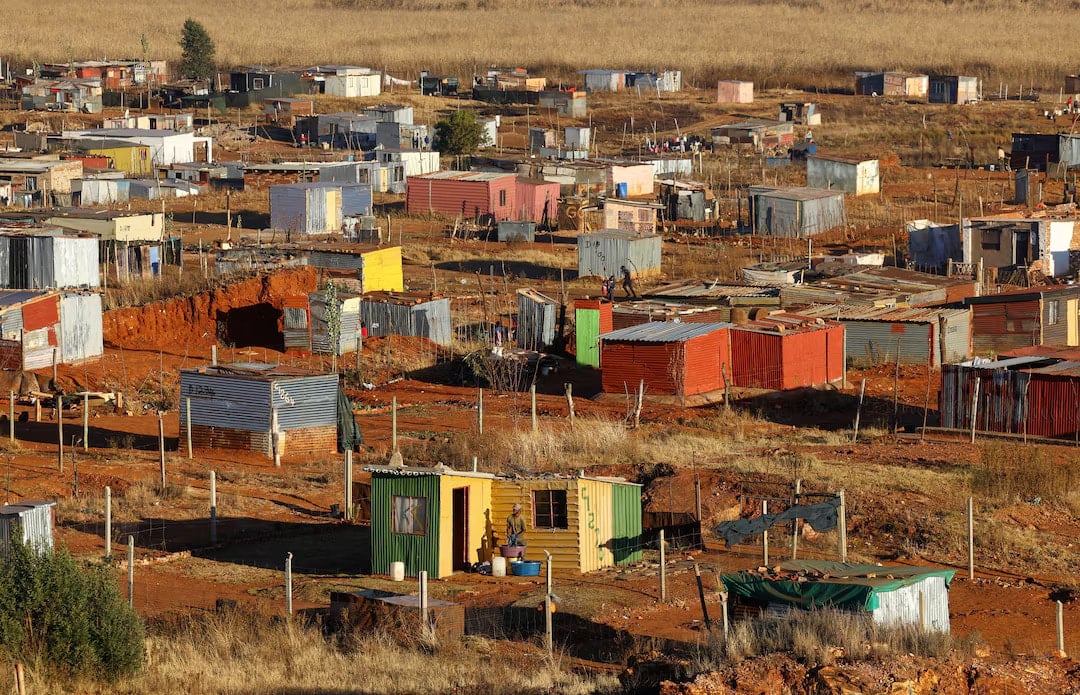

We adopted a qualitative explanatory study design, informed by socioecological theory, and analysed emerging data using inductive and deductive thematic analyses. The study design is appropriate given our aim to provide an in-depth understanding of barriers and enablers of antenatal service use among pregnant adolescent girls. The data were drawn from a larger cross-sectional study that focused on understanding the lived experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents in an urban informal settlement in Nairobi, Kenya. The choice of the study setting was purposive, given anecdotal reports of a spike in adolescent pregnancy related to COVID-19, and the site has been the Nairobi Urban Health and Demographic Surveillance System established by our centre since 2002. Korogocho is one of the largest low-income urban informal settlements in Nairobi. It is characterised by a high population density, with a third of the population being adolescents, poverty, and a lack of proper sanitation and infrastructure.25 Adolescent girls living in informal settlements have a higher likelihood of having unintended pregnancies and limited access to healthcare services.26 Furthermore, informal settlements are characterised by a lack of access to quality obstetric care.27

The authors of this paper are seasoned researchers in sexual, reproductive and adolescent health in sub-Saharan Africa. The second and third authors have extensive experience conducting research on adolescent sexual and reproductive health in sub-Saharan African countries.28 29 Additionally, the authors are residents of Nairobi and are familiar with the issue and study setting. This familiarity with this issue is an added value to the research, helping to navigate data collection and contextually interpret findings. While none of the authors had experienced early childbearing, two of our research assistants who conducted the interviews did. The first author also conducted some of the interviews. None of us had a prior relationship with the participants.

We purposively selected 22 adolescent girls aged 13–19 who were either pregnant or had given birth. We collaborated with a local community-based organisation that has over 20 years of experience in youth programming to choose eligible girls from each village within the community. We included adolescent girls who were either pregnant (n=2) or had given birth (n=20). Although only two of the girls were pregnant during the interviews, all had gone through pregnancy recently. We made sure to include participants with different backgrounds in terms of age, education and pregnancy experiences to capture a wide range of perspectives. We prioritised the privacy and confidentiality of the adolescents during the selection process. In addition, we purposefully chose 10 parents or guardians of pregnant or parenting adolescents, as well as three healthcare providers, to gain insight into the experiences of pregnant and parenting adolescents with antenatal services. Purposive sampling enabled us to select diverse respondents across the study setting. Table 1 summarises the sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant and parenting adolescents.

Table 1

Sociodemographic characteristics of pregnant and parenting adolescents and parents

The interviews were conducted between October and November 2022 by five well-trained research assistants. All the research assistants had a bachelor’s degree or higher. Apart from being residents of Nairobi, the research assistants also had experience in conducting in-depth interviews in informal settlements. Our research assistants were able to establish a rapport with pregnant and parenting girls by drawing on their personal experiences. This allowed the girls to feel at ease enough to tell their stories. Two of the research assistants had a pregnancy when they were adolescents. To acquaint them with the instruments, the research assistants underwent a 5-day training before the start of data collection. Each assistant conducted a pilot interview to test the interview guide. The in-depth interviews lasted roughly ninety minutes on average. With the participants’ signed informed consent, the interviews were tape-recorded. Using the original recordings as a reference. Interviews were conducted in Kiswahili, and then translated and transcribed into English. Five bilingual translators translated and transcribed the interviews verbatim into English, and an experienced translator reviewed and quality-checked the transcripts. We limited our attention in this paper to the experiences of ANC, even though the interviews covered a wide range of issues. The interview guide, informed by the socioecological model, emphasises individual, interpersonal and systemic factors that influence ANC utilisation among adolescents. Additionally, the interview guide is provided as online supplemental file 1.

We made sure to be thorough and reliable to ensure that our findings were accurate and trustworthy. We were careful, transparent and critical, constantly reviewing our methods and results while exploring other possible explanations. To confirm that the data were complete and accurate, we compared transcript samples with the audio recordings and looked at the perspectives of different participants in the study, considering both positive and negative views. We used NVivo software for data analysis. Interviews were audio recorded and transcribed verbatim, which created a detailed audit trail of our data collection and analysis processes. To strengthen the credibility of our analysis, we used reflexive journaling and discussed emerging findings within our research team. We conducted a validation workshop specifically for pregnant and parenting adolescents, during which the findings were presented to them. This provided an opportunity for participants to confirm the findings, identify any gaps and offer suggestions for addressing the challenges they face. Our triangulation of diverse views from adolescent girls, parents and health providers and the use of socioecological theory also ensured rigour and trustworthiness.

We trained the research assistants on research ethics before entry into the field. In addition, we conducted community mobilisation meetings to inform community leaders about the study and to seek their consent to conduct the study. Participation was voluntary, and the privacy and confidentiality of all participants were respected throughout the study. We informed the participants about the aims of the study and their right to respond to questions they are comfortable answering or withdraw their participation at any time without fearing any repercussions. All participants provided written informed consent/assent before being engaged in the study. For participants younger than 18 years who lived with their parents, parental or caregiver written consent was obtained in addition to the participant providing written assent. All data were anonymised.

Although patients were not directly involved in the study, public engagement was integral to the research. An agenda-setting workshop was conducted in 2019, which convened key stakeholders from various sub-Saharan African countries.30 At the inception of the project, the study was presented to community stakeholders, including pregnant and parenting adolescents, community leaders, educators, parents, government representatives and representatives from community-based organisations. Additionally, a validation meeting was organised with these stakeholders, separately for pregnant and parenting adolescents and other stakeholders, to present the findings, evaluate their alignment with the community’s experiences and discuss strategies to address the identified challenges. Finally, a dissemination meeting was held with all stakeholders involved.

We used NVIVO software to code the data. All transcripts that directly relate to girls’ ANC experiences were curated and coded separately by AA. AIA, who is well experienced in qualitative data analysis, reviewed the emerging codes and themes separately. Both AA and AIA reflected and agreed on the emerging codes and themes. The data were analysed using inductive and deductive thematic analyses informed by socioecological theory. Data on themes that specifically address barriers and enablers of prenatal care among pregnant girls were coded and categorised to provide context for the analysis. The analysis began with a reflexive reading of the transcripts and immersion in the data, which involves reflecting on and engaging with the data, observing information, experiences and narratives relevant to the research objectives.

We began by highlighting the views of respondents on the timing of ANC among pregnant adolescents. Participants’ views on the barriers and facilitators to ANC are then described.

This theme captures when pregnant adolescents initiated ANC from the perspective of girls, their parents, and health providers. All informants agree that pregnant adolescents often start ANC late and, as a result, are unable to complete the recommended number of ANC visits. In most cases, ANC was initiated in the second trimester, like in the case of the girl below, who started ANC visits in the seventh month:

That was on Sunday, while we were going to church, when I went for the massage. On Tuesday, I went to the clinic, and the nurse was surprised that I was starting my first clinic when I was almost giving birth, and that’s when she examined me and told me that the baby was healthy. (In-depth Interview (IDI) participant 5, late adolescent mother)

Such cases were very common, and only a few of the girls interviewed started ANC at 4 or 5 months. Out of 20 adolescent mothers, 12 of them initiated ANC during the second trimester and 1 during the third trimester. This late initiation of ANC resulted in having only a few visits during the pregnancy. In the case of a mother’s account of her daughter’s pregnancy, she only attended one ANC visit, and that was after the mother found out about the pregnancy:

Clinic, she only went once, I’m telling you how I found out about it late. When I knew about it, it was on a Sunday, and the next day, on Monday, I took her to the clinic. And when she went like that once and was given the next date of going, she didn’t manage to go because she gave birth before that date, but the baby I took by myself and finished everything. (Mother to a parenting adolescent, 41-year-old)

Health workers alluded to the pregnant girls’ late initiation of ANC during the interviews. To the health workers interviewed, late initiation of ANC is rather the norm and not an exception:

aaaah [shaking her head] …when they almost giving birth [laughs]…yeah. For those who are not living with strict parents or guardians, such as aunts who are well aware of matters of birth, or whoever they live with. If this parent or guardian does not take the initiative, it is difficult for the teenager to present themselves at the hospital. Hence, most of the time, you find that maybe they just come for delivery [laughs], or they come in their third trimester, having completely concealed the pregnancy to the extent that you may not even notice that they are pregnant. So, they mostly come for a visit in their third trimester. (Provider 3, Korogocho)

Based on social-ecological theory, our findings on the barriers and enablers of ANC use are clustered into three themes: (1) intrapersonal factors, (2) interpersonal factors, and (3) organisational factors. Extracts from relevant data are used to illustrate each theme. Figure 1 shows the main themes and subthemes.

Intrapersonal factors

Individual characteristics (education, occupation, race/ethnicity and residence in an urban or rural area) and health beliefs (people’s attitudes, values and knowledge towards health and health services) are intrapersonal factors that can influence the use of ANC services according to social-ecological theory. Pregnant girls in the study setting faced barriers to initiating ANC due to factors such as young age, naivety and lack of autonomy in decision-making. Several adolescent girls who were interviewed stated that they were embarrassed and afraid to go to health facilities for ANC because they were young. They worried that people would judge them if they were discovered to be pregnant at such a young age and while still in school. As a result, pregnant girls delay attending prenatal care to avoid being noticed and judged. Pregnant girls decided to attend school rather than ANC due to their young age and the need to continue their education for as long as it is possible to conceal their pregnancy. One adolescent mother recounted:

I was still young and could not imagine going to the clinic with such a big belly, how would people see me? (IDI participant 19, mid-adolescent mother)

Most girls interviewed attributed their delay in seeking ANC to their ignorance. They reported that they were not sure when to start ANC, what services are offered and how helpful it is. According to one health worker we interviewed, pregnant adolescents often only knew that women give birth in clinics, but were not aware that pregnant women attend ANC. Some girls only learnt about ANC after their parents/guardians found out about the pregnancy and encouraged them to seek ANC, as in the following case.

With me, I didn’t know of such things. It was my first time and so my mum would tell me that I needed to go to the clinic. (IDI participant 8, late adolescent mother)

A few discovered they were pregnant late and some who discovered early were in denial, which prevented them from accessing ANC early. Others were informed by family, friends or community members of their pregnancy since they did not recognise it. Since most adolescent pregnancies were unintended, girls took time to notice the pregnancy or acknowledge it. Instead of acknowledging the pregnancy and initiating ANC, they made efforts to terminate the pregnancy and began ANC when all efforts to abort the pregnancy were unsuccessful and the pregnancy became visible.

Interpersonal factors

Although adolescent pregnancies are common in the study setting, adolescent pregnancy is highly stigmatised in the community. Most of the girls interviewed expressed feelings of shame and guilt about their pregnancy, which led them to self-isolate, including from health providers. They feared being seen by health providers and often thought health providers would judge and insult them, as one interviewee recounted:

I feared people and feared the doctors because probably they would judge or insult me. So, she (mother) told me no that should not be the case and so she offered to take me. (IDI participant 17, late adolescent mother)

Pregnant girls chose to isolate themselves and limit their social circle due to societal stigma. To avoid being seen by those who were backbiting them, several of the girls who were interviewed said they would only go out at night. Others chose to cover up so as not to be noticed by many people, as the girl below did:

It was challenging, because as I go, I would not go like I am, I would usually find a Maasai sheet and wear a very big sweater, with the Maasai sheet I would cover myself and hold it to cover the front part [laughter]. That is how I would go to the clinic. (IDI participant 16, late adolescent mother)

At the facility, a few of the girls felt ashamed because they were attended to with older women. At the clinic, people gazed or pointed at them. One interviewee had to transfer to a different clinic outside of her community due to heightened discrimination because her mother was well known in the facility.

eeeh… it is because you can attend the clinic only to find that you are the only one there with a protruding belly, alone, you have to feel ashamed since there are other grown women there. Moreover, in the hospital that I used to attend, my mum was employed there as a cleaner. Hence, I used to wonder what she used to say in that hospital about me. So, you have to be ashamed as people start staring and pointing at you. (IDI participant 12, late adolescent mother)

Additionally, a lack of support and understanding from their immediate family hindered adolescent girls’ access to ANC in Korogocho. In certain instances, girls were expelled from their homes after their parents or guardians discovered their pregnancy, or their financial support was withdrawn. Lack of family support hindered them from seeking ANC.

However, family members and guardians such as aunties, mothers and sisters were important enablers of ANC use among pregnant adolescent girls. They support girls in deciding when and where to go to the clinic, and inform them about the benefits of ANC. Support from family members included advising young girls to go to the clinic and accompanying them there.

Yes, after the first visit, which she (Aunt) took me to, with the rest that I was scheduled for, I would usually find someone to take me. […] Someone like my friend, my best friend, or my cousin. Those are the only ones that I would usually walk with most of the time. (IDI participant 20, late adolescent mother)

I started when I was four months into my pregnancy. My aunt, who is a doctor, is the one who approached me and asked whether I had started going to the clinic. (IDI participant 16, late adolescent mother)

Furthermore, a few parents registered for the Linda Mama insurance (a government-initiated insurance scheme to expand access to free maternity care) to ensure that their pregnant daughter could access free maternal healthcare services. This is illustrated in the quote below:

After delivery… I had taken Linda Mama, and so it catered for her delivery at Mama Lucy Hospital. The only problem we had was getting food, but the good thing was that I was still going to work by that time. Before going to work, I ensured that I cooked for her first, and when I got back. She did not have so many challenges. (Mother 1 to a Pregnant/Parenting Adolescent (PPA), 38 years)

In a landscape where adolescent pregnancy is often met with abandonment, the study uncovered a striking counternarrative: partner involvement emerged as a cornerstone of resilience for a very few girls, facilitating access to ANC. Far from the stereotype of absent fathers, some male partners supported their partners in ANC visits, as illuminated by one late adolescent mother:

We went to the clinic together… He skipped work just to take me there and back. When I felt sick, he’d rush me to the hospital and demand answers from the doctors: ‘What’s wrong? How do we fix it?’ (IDI participant late adolescent mother)

Here, the partner’s role transcended mere accompaniment. He shouldered the logistical burdens (navigating transport, sacrificing income) and championed her health as a priority. His presence was not passive—it was a radical defiance of norms that often frame adolescent pregnancy as a ‘girl’s problem’.

Organisational factors (facility level)

Three organisational factors emerged from our data: providers’ attitudes and user fees and patient-provider communication. We describe these factors below:

Health providers’ attitudes

While girls feared healthcare providers and worried that they would judge them, which made them seek ANC late or not at all, their experience in the clinic was, however, largely positive. Both the girls and health workers interviewed reported that healthcare providers were respectful and counselled girls, which facilitated services use among pregnant girls. For some adolescents, respectful treatment shattered their expectations of hostility. Providers who coupled clinical guidance with gentle, affirming dialogue became unexpected allies. As one late adolescent mother recounted:

They never spoke to me badly—they only advised me: ‘Take good care of yourself, eat well, and take fruits’. (IDI participant 4, late adolescent mother)

Another participant highlighted how a provider’s curiosity without condemnation opened a path to trust:

When I got there, they just asked me if I was a student. I said yes. Then she asked, ‘Why did you agree to get pregnant early?’ I told her the whole story. She told me, ‘Don’t give up—that’s how life is. Have your baby and go back to school.’ (IDI participant 2, late adolescent mother)

Here, probing questions were framed not as accusations but as invitations to be heard—a radical departure from the judgement girls anticipated. As one participant’s voice echoes: “They treated me like I mattered.” In contexts where pregnant girls are rendered invisible, these moments of recognition are revolutionary, proof that respectful care is not a luxury, but a lifeline.

Nevertheless, a few girls reported that healthcare providers treated them poorly, which made them dread their clinic visits. Some reported that healthcare providers verbally abused them. They demeaned them by using derogatory words because of their early pregnancy and young age. Health workers often questioned them on why they got pregnant and asked, often in a judgemental tone, who was responsible for their pregnancy. One interviewee recounted what a nurse said to her:

Doctors are not friendly… the nurse was asking, you are shouting my name, “sister” (nurse), when he was inserting his thing (penis) inside you, were you shouting? (IDI participant 11, mid-adolescent mother).

Some interviewees recounted that there was little or no privacy and confidentiality when dealing with pregnant adolescents. To avoid being recognised by those in the line, a few girls stated that they had to cover their heads and wear long outfits. Others claimed they found it difficult to communicate because there were up to three healthcare providers in the room.

I used to feel very uncomfortable, because whenever the line [queue] was moving and I was next in line, I would feel like running away and going back home. After all, inside the room, it’s not just one doctor, it’s like two or three doctors. With the queue where there are pregnant women, I would ask myself, “What is it that they would tell me when I go in?” [laughter]. They (other women) would even push me to move. (IDI participant 16, late adolescent mother)

One public health officer working at the county health department also stated that girls were ill-treated by providers and attributed it to a lack of training on adolescent-responsive services. Sometimes, high workload and COVID-19 limitations in public hospitals led the healthcare providers to provide services only to those seeking emergency services. Since the adolescents are treated like all other women, they may not speak up during ANC clinics and classes. Such is the case of the one girl who lost her pregnancy at 8 months because she did not recognise her situation as an emergency and the health providers did not attend to her specifically:

When I would go to the clinic, they would say that in case someone did not have any problem, they should go back home, saying that they would not provide services for those who were attending the clinic for the first time. It was only during my first visit when they took good care of me until I was eight months pregnant, when I would not feel the baby moving, and I was reclined on one side. For me, I thought that was normal. It was only from the clinic visit that I would have known that was not normal, but instead, we were not attended to, but asked to go back home…. (IDI participant 20, late adolescent mother)

User fees

Despite the removal of user fees for ANC services in public health facilities, other costs associated with care, such as medicines, tests and recommended diet, remained a challenge for most pregnant adolescent girls. Several girls stated they lacked the right food and maternity clothes. When required to take tests before their next visit, some adolescent girls could not afford to pay for the required tests and, as a result, missed their appointment dates.

Sometimes you are asked to take some tests at the clinic, which you need to pay for, but because you do not have money, you do not take the test, and the clinic date approaches and passes without you taking the test. (IDI participant 11, mid-adolescent mother).

The Linda Mama insurance programme was widely used by adolescent girls upon initiation of ANC. The insurance covered ANC in public hospitals, including delivery services, and was free of charge. A community health volunteer (CHV) reported that she advised pregnant women to sign up for the Linda Mama programme.

One can go to the clinic in their sixth month, but since there are things like Linda Mama that assist, you tell them the importance of Linda Mama, so whether they go to Mama Lucy or Pumwani [public health facilities in Nairobi] to deliver it will cover both mother and baby for a year. You tell them that there may be complications in the future, so they should keep their Linda Mama card safely and ensure they go to the clinics. (CHV, Korogocho)

Health insurance also covers the delivery fees, including caesarean section and treatment of the baby in case of any issues after birth. This motivated the adolescent girls to go for ANC in order to receive the free services, as in the case below.

…you are just treated for free. You just take Linda Mama, which you will be using. When you give birth, that is what will pay. If I didn’t take it, I would have to sell land, land would be sold, and a cow. (IDI participant 11, mid-adolescent mother)

I needed to get Mum Care and Linda Mama and so, and that is why I started attending the clinic. (IDI participant 15, late adolescent mother)

Patient-provider communication

In cases where the health providers gave appropriate treatment to the pregnant adolescent girls, they had a positive experience and continued with the ANC. Guiding and counselling were important for the girls, and giving them appropriate information on the importance of ANC.

They (nurses) just ask me questions, how you are supposed to be, how to care for the baby, how to care for the pregnancy, you are supposed to dress in clothes that are not tight because they press the baby, you need to do exercise. (IDI participant 12, mid-adolescent mother)

Informed by socioecological theory, we examined the barriers and enablers of ANC services use among adolescent girls in a low-income urban informal settlement. The study findings show that pregnant adolescents face a myriad of challenges that lead to delayed initiation of ANC. These factors operate at multiple levels, including intrapersonal, interpersonal and organisational levels.

At the individual level, we found that young age, naivety, lack of autonomy in decision-making, late discovery and acceptance of pregnancy, internalised stigma and lack of knowledge hinder pregnant girls from initiating ANC early. These findings are consistent with previous studies.11 13 14 Previous studies in Uganda and Kenya found that pregnant girls initiated ANC late or not at all because they feared walking around pregnant, recognised their pregnancy late and lacked knowledge of ANC.13 15 Because of their young age and fearing the consequences of people finding out about their pregnancy, girls hide their pregnancy rather than initiate ANC. Our findings align with other studies that demonstrate a correlation between the desire for pregnancy and the delayed initiation or non-initiation of ANC.18 31 The late start of ANC is also linked to the discomforts associated with disclosing pregnancy, the stigma of early pregnancy in young women11 32 and the fear of reproach from healthcare workers. Additionally, the late recognition and acceptance of pregnancy,17 along with limited knowledge of maternal healthcare, lead to delayed ANC initiation and fewer clinic visits.8 17 Addressing gaps in knowledge regarding ANC among pregnant adolescent girls can be achieved by integrating the significance of ANC services into the school curriculum and active community engagement by health workers and healthcare providers.

Consistent with previous studies,17 33 our study shows that interpersonal factors are related to girls’ use and non-use of ANC. The social stigma faced by pregnant adolescents led some of them into self-isolation. As a result, they were reluctant to attend the ANC clinic where other people would see and be able to identify them.33 Social stigma is a form of sanction for girls who deviate from the norm of saving sex for marriage, since pregnancy is evidence of such a deviation. Although adolescent pregnancy is common in the study setting, it remains highly stigmatised. Pregnant girls often hide their pregnancy due to fear of social sanction, and as a result, they may delay seeking ANC until all efforts to abort the pregnancy have failed. Addressing internalised stigma presents significant challenges, particularly due to the prevailing social norms surrounding adolescent pregnancy, which serve as a primary driver of stigma. The stigma associated with adolescent pregnancy is unlikely to diminish without a transformation of the social norms that perpetuate it.

Our findings reveal a stark divide in ANC engagement shaped by familial solidarity. Pregnant adolescents who received support from their families, especially mothers or guardians, or partners, were far more likely to overcome their fears of disclosure and seek ANC, even when grappling with shame or uncertainty. This support manifested in tangible, life-saving ways: families provided financial resources for medical costs, emotional guidance to navigate stigma, practical advocacy during clinical visits, and relentless reassurance that countered societal rejection. When partners engage actively and empathetically, they become co-architects of care, buffering girls against stigma, financial ruin and systemic neglect. Their involvement did not just facilitate ANC; it rewrote scripts of shame into stories of solidarity, proving that paternal support can be as vital as medical intervention in safeguarding maternal health.

Conversely, the absence of such support created insurmountable barriers. Adolescents without familial backing described profound isolation, with many delaying or entirely avoiding ANC due to unaffordable costs, paralysing anxiety or the crushing burden of navigating pregnancy alone. Notably, parental financial support emerged as a non-negotiable lifeline in contexts where partners routinely denied paternity, abandoning adolescents who had no alternative income. When this economic safety net was absent, girls faced agonising trade-offs: skipping ANC to ration scarce funds for food or shelter. To prevent early pregnancy from severing critical familial bonds, targeted efforts must urgently bridge the chasm between pregnant adolescents and their parents—a divide often fueled by anger, shame and fractured trust. Restoring this connection is not merely beneficial but lifesaving: parental support remains a vital lifeline for adolescents navigating stigma, healthcare access and economic precarity. Community-led mediation programmes, peer support networks and parent-adolescent counselling can transform silent divides into spaces of mutual understanding, ensuring adolescents are not abandoned in their most vulnerable moments.

At the organisational level, we found that some pregnant adolescent girls were unable to afford user fees related to ANC, which hindered their attendance at ANC. However, the availability of free maternal healthcare through the national insurance, ‘Linda Mama’, enabled pregnant adolescent girls to access ANC. Previous studies have highlighted the importance of Linda Mama in providing equal access to maternal healthcare services in Kenya.34–36 This is particularly true for pregnant adolescents from impoverished backgrounds in Kenya, especially those living in low-income urban informal settlements. Despite this, pregnant adolescent girls voiced concerns over a lack of money for medications and nutrition recommended during ANC, often resulting in non-adherence to healthcare providers’ recommendations.

Consistent with previous studies,32 37 respectful care emerged as a transformative force in breaking the cycle of fear and distrust. Pregnant adolescents described how an initial encounter marked by warmth, dignity and compassionate dialogue from healthcare providers dissolved their apprehension, turning clinical spaces from sites of judgement into sanctuaries of trust. When providers replaced scorn with solidarity—offering nutritional advice as earnestly as prenatal vitamins, or reframing ‘mistakes’ as survivable setbacks—they did more than deliver care. They rewrote scripts of shame, proving that compassion could coexist with clinical rigour.

In stark contrast, encounters marred by dismissive remarks, public exposure of sensitive health details, or breaches of privacy had a chilling effect. Adolescents recounted how humiliating experiences, such as being scolded for their pregnancy in crowded waiting rooms or having their concerns ignored, sent them retreating into silence. These systemic failures did not just limit access; they entrenched cycles of avoidance, disproportionately harming those already marginalised by poverty or partner abandonment. To transform clinics into sanctuaries of trust for pregnant adolescents, governments and health systems must urgently reimagine adolescent-friendly services as holistic, dignity-first ecosystems. This demands training of providers on adolescent-responsive care and having zero-tolerance policies for breaches of privacy.

This study’s strength lies in the rigorous and in-depth analysis of triangulated perspectives of parenting adolescent girls, parents and health providers on pregnant adolescent girls’ use of ANC informed by the socioecological framework. However, the study is not without limitations. The study’s focus on girls in a low-income urban informal settlement means its findings might not apply to all informal settlements, areas with more resources, or rural environments. The sample we analysed did not include married adolescents, and as a result, their experiences may not be adequately represented in our findings, although it is uncommon for adolescents to be married before becoming pregnant in the study setting. Considering the sensitivity surrounding adolescent sexual and reproductive health, it is important to acknowledge the potential for response bias, as participants’ answers may be shaped by social expectations or fear of being judged. As researchers based in Nairobi with expertise in reproductive health, our perspectives may have influenced the interpretation of findings, while simultaneously enhancing the interpretation given our understanding of the local context. Overall, the research offers valuable insights that are essential for creating a health system attuned to the specific needs of pregnant teenagers.

Pregnant adolescent girls face unique challenges that prevent them from accessing ANC early and completing the recommended number of visits. These challenges include intrapersonal factors such as young age, ignorance and internalised stigma, as well as interpersonal and organisational factors like societal stigma, discrimination, user fees and health providers’ attitudes. Parents, other family members, and health providers play a key role in enabling ANC attendance by offering various forms of support to pregnant girls, including counselling and accompanying girls to clinics. There is a need for specialised services for pregnant adolescents by creating youth-friendly services to improve access to ANC among adolescents. In addition, good patient-provider communication, privacy and confidentiality may allay girls’ fears and increase the use of ANC services. Interventions to improve early initiation of ANC should address the social stigma associated with early and unintended pregnancy and make health facilities responsive to the needs of pregnant girls.

Data are available upon reasonable request.

Not applicable.

This study involves human participants and was approved by AMREF Ethics and Scientific Review Committee (AMREF ESRC), no. P1240/2022, and Kenya National Commission for Science, Technology, and Innovation (NACOSTI), reference no. NACOST-NACOSTI/P/22/19653. Participants gave informed consent to participate in the study before taking part.

The authors would like to acknowledge Miss Koch, Kenya, for the partnership and for enabling the fieldwork process. We extend our appreciation to the pregnant and parenting adolescent girls and the other participants who dedicated their time and shared their experiences freely. Finally, our gratitude goes to the research assistants who collected the data.