The Victory of Zionism: Imperial Chess

When Britain issued the Balfour Declaration in 1917, supporting "the establishment in Palestine of a national home for the Jewish people," they weren't acting from sudden philanthropic impulse. They were making a cold, calculated geopolitical move in the greatest game of imperial chess ever played.

By the early 20th century, the Ottoman Empire—the "sick man of Europe"—was in terminal decline after six centuries of dominance. Its territories stretched from the Balkans through Anatolia, across the Levant, down the Arabian Peninsula, and across North Africa. As this empire gasped its last breaths, imperial powers circled the carcass, each seeking strategic advantage in the post-Ottoman order.

A critical aspect of this imperial reshuffling: the Arab populations across North Africa and the Middle East didn't exist as independent nation-states. For centuries, Arabs had lived under Ottoman rule, organized into administrative provinces (vilayets) with no independent national identities as we understand them today. "Syria," "Iraq," "Lebanon," "Libya"—these weren't countries but geographic expressions. The modern borders of virtually every Arab state were drawn by European powers with minimal consideration for tribal, religious, or ethnic realities on the ground.

The concept of distinctive Palestinian nationalism barely existed in 1917. Local Arab identity was primarily focused on clan, village, religion, or at most, regional attachment (to Greater Syria, for instance). Pan-Arab nationalism was embryonic, championed by a small educated elite rather than a mass movement. The Arabs of Palestine generally considered themselves part of bilad al-sham (Greater Syria), not a distinct Palestinian entity.

This absence of established nation-states gave European powers extraordinary latitude to redraw maps according to their strategic interests. France and Britain effectively carved up the region in the 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement, establishing artificial borders that suited imperial management rather than local realities. Straight lines drawn through deserts by diplomats in London and Paris created countries with little historical precedent.

Geography dictated Britain's priorities. The Suez Canal, opened in 1869, had become the jugular vein of the British Empire—the critical shortcut to India (the "crown jewel") and Asian possessions. Around 40% of Britain's global trade passed through this narrow waterway. Whoever controlled the eastern Mediterranean coastline could potentially threaten this vital artery.

Palestine occupied a critical position in this geopolitical equation: it sat at the crossroads of three continents, bordered the Mediterranean, and offered a buffer to protect Suez. For a naval power like Britain, Palestine represented not just territory but strategic depth.

The demographic reality of Palestine factored into British calculations. In the early 20th century, the region had a relatively sparse population, approximately 700,000 people by most estimates in 1914. Census data from this period is imperfect, but Ottoman tax records and later British surveys indicate the region was significantly underpopulated relative to its historical capacity.

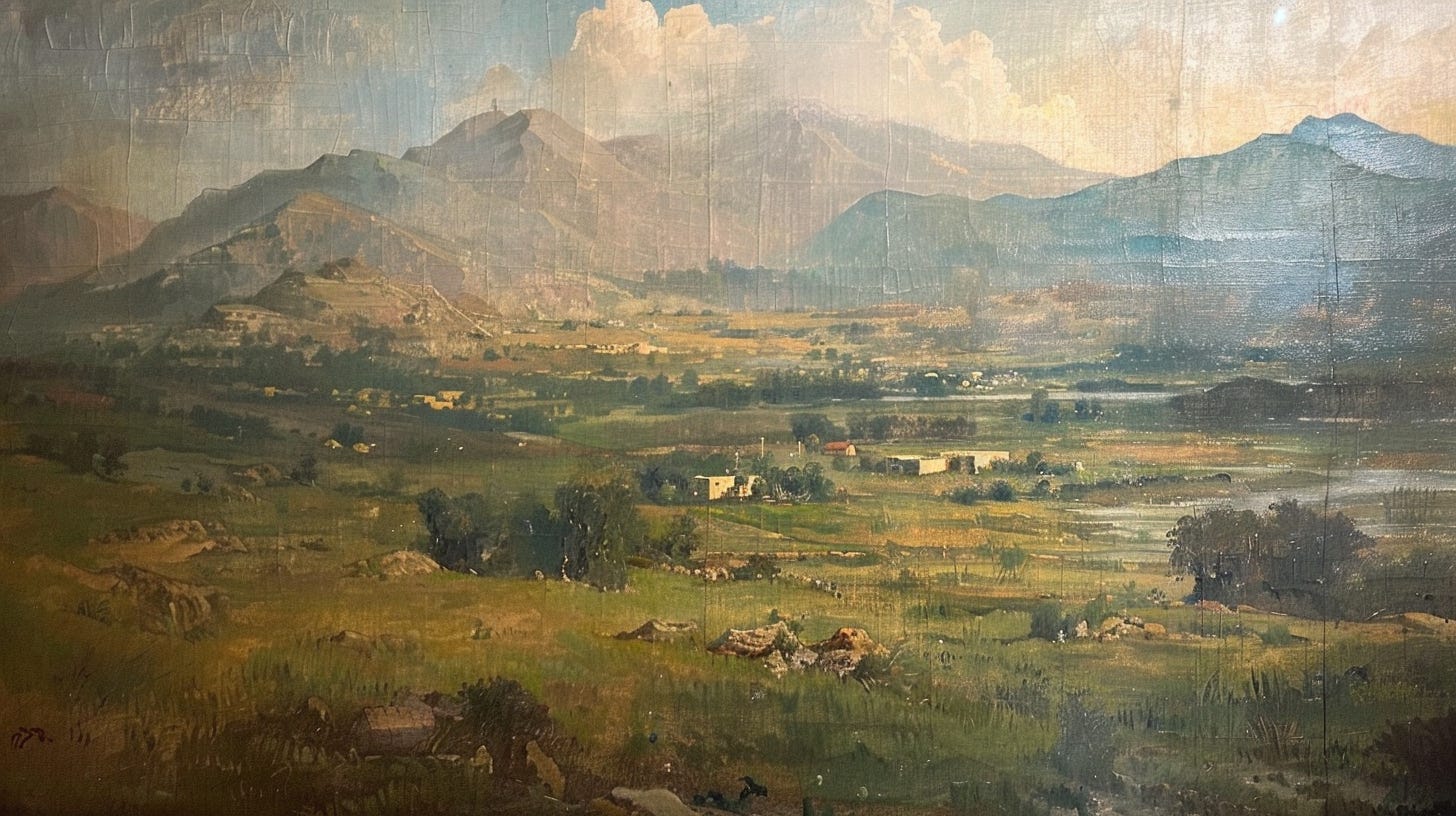

The area's demographic vacancy resulted from centuries of neglect, recurrent plagues, and economic stagnation under late Ottoman rule. Large sections of what was once fertile land had deteriorated into swamps and deserts. Mark Twain, visiting in 1867, described it as "a desolate country whose soil is rich enough, but is given over wholly to weeds—a silent, mournful expanse."

Population density in Palestine (roughly 25-30 people per square kilometer) stood in stark contrast to Europe, where countries like Germany and Britain had 120-250 people per square kilometer. Even compared to neighboring Egypt, with its concentrated population along the Nile, Palestine was sparsely inhabited.

This was not an empty land, but it was an underdeveloped one with capacity for significant population growth—a factor that made it attractive for British strategic planning.

What's often forgotten in contemporary discussions is that the entire concept of fixed borders and nation-states was foreign to the region. The Ottoman administrative system operated through loose control of territories where tribal and religious affiliations mattered more than national identity. When European powers arrived with their Westphalian concepts of sovereignty and national borders, they imposed an entirely different political framework on the region.

The artificial nature of these new borders is starkly illustrated by Iraq, cobbled together from three distinct Ottoman provinces (Baghdad, Basra, and Mosul) with different religious and ethnic majorities. Similarly, Jordan was essentially invented as a consolation prize for the Hashemite family. Libya combined three historically separate regions (Tripolitania, Cyrenaica, and Fezzan) with little in common. These artificial creations suited imperial management but created the foundation for decades of instability.

Britain faced a multi-dimensional strategic problem: how to secure their position in the eastern Mediterranean against rival powers while minimizing direct administrative costs. Their solution followed a classic imperial pattern—find a local population whose interests align with yours and who can serve as a reliable proxy.

Jewish settlers fit this requirement perfectly. Unlike Arab populations, who might be drawn to pan-Arab or pan-Islamic movements (potentially sympathetic to rival Ottoman or German interests), the Zionist movement had no natural imperial patron. They represented a population with Western technical skills, democratic leanings, and a desperate need for protection—the perfect client community.

The Zionist leadership understood this dynamic explicitly. Chaim Weizmann, the Russian-born chemist who became the movement's chief diplomat, cultivated relationships throughout the British establishment. His scientific contributions to the British war effort—developing an improved process for producing acetone, crucial for manufacturing explosives—gave him access to decision-makers.

More importantly, Weizmann mastered the art of framing Zionist aspirations regarding British imperial interests. "A Jewish Palestine would be a safeguard to England, in particular in respect to the Suez Canal," he argued to British officials, positioning a Jewish state as a buffer protecting Britain's vital maritime routes.

The timing was equally significant. World War I had triggered the collapse of empires and the emergence of nation-states across Europe. New countries were being carved from imperial territories based on ethnic and national identities—Czechoslovakia, Poland, Yugoslavia, Finland, and the Baltic states. The principle of national self-determination was reshaping the European map.

This same period saw massive population transfers becoming normalized as a solution to ethnic conflicts. Between 1912 and 1925, approximately 1.5 million Greeks were relocated from Turkey to Greece, and about 500,000 Turks moved in the opposite direction—a "population exchange" formalized by the 1923 Treaty of Lausanne. The collapse of the Ottoman Empire triggered similar movements throughout the Middle East and the Balkans.

These population transfers weren't anomalies but standard practice in the post-imperial reorganization. The Indian subcontinent would later experience an even larger population exchange, with approximately 14-16 million people relocated between India and Pakistan after the 1947 partition. The era of empire dissolution consistently produced massive population movements as new national identities were forged.

Meanwhile, across the Middle East, imperial powers were installing friendly regimes with minimal local input. Britain placed Hashemite kings on the thrones of newly created Iraq and Transjordan. France divided Syria to create Lebanon with a tenuous Christian majority. Colonial powers drew borders across the Maghreb with ruler-straight lines through the Sahara. In this context, supporting Jewish settlement in a portion of Palestine was entirely consistent with how European powers were restructuring the entire region.

Image below: photograph of British and Iraqi dignitaries in Baghdad from 1923 during the era of Mandatory Iraq.

In this context, the idea of Jewish resettlement in Palestine appeared not as an anomaly but as part of a broader pattern of post-imperial national reorganization happening worldwide. What distinguished the Jewish case was not the concept but the historical time gap—they were returning to a homeland after two millennia rather than immediately after imperial collapse.

Britain's support for Zionism also had domestic political dimensions. Influential British figures held religious views that favored Jewish restoration to the Holy Land. Lord Shaftesbury had advocated Jewish return decades earlier, popularizing the phrase "a land without a people for a people without a land." Prime Minister David Lloyd George acknowledged being more familiar with biblical geography than modern maps.

These cultural and religious factors, however, were secondary to strategic interests. As British Foreign Secretary Arthur Balfour candidly admitted in a private memo: "The contradiction between promising the land to Arabs and Jews is not accidental... For in Palestine we do not propose even to go through the form of consulting the wishes of the present inhabitants."

Britain's support for a Jewish national home also served as a counterweight to French ambitions in the region. The 1916 Sykes-Picot Agreement had divided Ottoman territories between the two powers, with France claiming what is now Syria and Lebanon. A British-aligned Jewish entity in Palestine created a buffer against French influence expanding southward toward the Suez Canal.

The results of Britain's strategic gambit proved mixed. The Balfour Declaration helped secure British control of Palestine through the post-war mandate system, but administering the territory between competing Jewish and Arab national aspirations became increasingly costly. By the 1930s, Britain found itself trapped between contradictory promises and escalating communal tensions.

What's remarkable about this history is how clearly it illustrates the gap between public justifications and strategic realities in imperial decision-making. Britain publicly framed the Balfour Declaration as supporting Jewish national aspirations, which it did, while quietly pursuing the protection of imperial lifelines.

The Jewish leadership, for their part, understood this dynamic perfectly. They didn't expect British support from altruism alone, but positioned their national project as serving British imperial interests. This alignment of interests—however temporary and ultimately fraught—created the diplomatic foundation for what would eventually become Israel. It represents a classic case of a small nation leveraging great power politics by positioning itself as useful to imperial strategy.

Understanding this context doesn't diminish the legitimacy of Jewish national aspirations or the achievements of the Zionist pioneers. Rather, it places them within the broader sweep of post-imperial reorganization that transformed the global map in the early 20th century.

Chapter 1 can be read here.