The Business Of Freedom: What Juneteenth Teaches Us About Black Wealth

Rihanna celebrates the launch of Fenty Beauty at ULTA Beauty in Los Angeles, California.

Getty Images for Fenty Beauty by RihannaOn June 19, 1865, Union troops arrived in Galveston, Texas, to enforce President Lincoln’s Emancipation Proclamation, delivering freedom to enslaved people more than two years after its signing. That date, now celebrated as Juneteenth, marks not just legal independence but also the beginning of an incomplete economic quest: the fight for Black wealth. Yet today, rising Black-led enterprises—from early 20th-century hair empires to interstate beauty megabrands—forge a new path toward legacy, ownership and intergenerational capital. For the newly freed, the bigger question following emancipation was, what does freedom mean without the financial foundation to sustain it? As we remember Juneteenth 160 years later, that same question continues to come up in Silicon Valley boardrooms, beauty labs in Los Angeles and venture capital offices in New York. The answer, it turns out, has been hiding in plain sight within the holiday itself: true freedom requires ownership.

Willie Robinson, who owns Libra Art and Studio-t puts up decorations over his business place ... More Thursday in preparation for the opening of Juneteenth celebrations.

Denver Post via Getty ImagesJuneteenth arguably represents one of America’s most entrepreneurial moments—a mass liberation that instantly created the world’s largest startup class. Suddenly, over four million people needed to build lives, businesses and generational wealth from nothing. They had no family offices, no inherited portfolios and no network effects from elite universities. What they had was necessity as the mother of invention. The parallels to today’s startup ecosystem are striking. Like any founder facing a market disruption, the newly freed had to quickly identify opportunities, bootstrap resources and scale. Within a generation of emancipation, Black Americans had accumulated wealth equivalent to hundreds of millions in today’s dollars. With that success, they built banks, launched newspapers, founded universities and created entire commercial districts. Then came the systematic destruction—through Jim Crow laws, redlining, urban renewal and what economists now recognize as the most successful wealth extraction program in American history.

Between 1910 and 1997, discriminatory lending practices gutted Black homeownership and economic stability. A 2008 study cited in the Harvard Civil Rights-Civil Liberties Law Review estimated that subprime loans alone wiped out between $164 and $213 billion in wealth from borrowers of color—calling it “the greatest loss of wealth for people of color in modern U.S. history.” That number doesn’t even account for earlier waves of extraction. Add to that the $200 million in Black-owned assets destroyed in the Tulsa Race Massacre in a single day, and the pattern becomes undeniable: the loss was generational, not merely financial.

Emancipation symbolized moral justice, but economic justice lagged. Reconstruction-era Black families were systematically denied land, access to banking and the homesteading opportunities white families received. Fast forward to 2022: the typical Black family held just $44,890 in median wealth versus $285,000 for white families—a staggering 6× gap, according to the Brookings Institution. And though overall median wealth rose during the pandemic, the racial wealth gap widened by nearly $50,000. Policies like the GI Bill, FHA loans and New Deal programs entrenched a structural advantage that Whites continue to benefit from.

Beyoncé celebrates the launch of her hair care line, CÉCRED, with an intimate gathering at The ... More Revery LA in Los Angeles, California.

WireImage via ParkwoodWealth in itself represents more than savings. Instead, it is a launchpad that enables risk-taking, business founding, wealth transfer across generations and capital access. But Black families have lagged behind without multilingual fluency in capital, bank loans, venture equity and homeownership. Numerous Black founders still struggle to raise F&F rounds by tapping sparse generational wealth; Black founders receive less than 1% of venture capital, despite being a little over 12% of the population. The 1% figure masks deeper structural issues: Black founders raising Series A rounds face average valuations 25% lower than comparable white-led startups, while 83% of VC partners are white men, creating what Harvard Business School calls “pattern recognition bias” in investment decisions. So Juneteenth remains, in many ways, an unfulfilled promise that represents a day to celebrate freedom while spotlighting the work that still lies ahead.

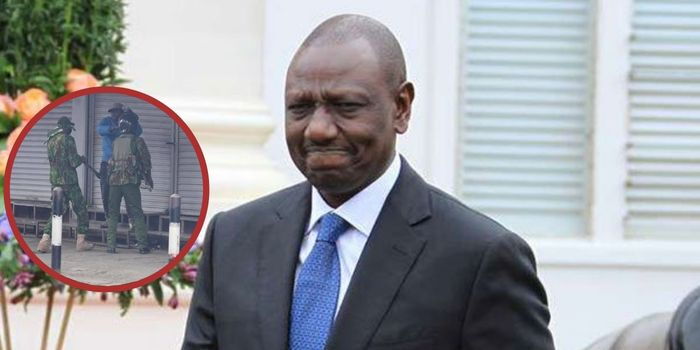

The first chapter of modern Black wealth began with Madam C.J. Walker, born Sarah Breedlove and emancipated in 1867. By age 37, she created a national hair-care empire for Black women, later hiring 20,000 sales agents, developing her factory, training schools and supply chain. Walker used wealth strategically—investing in real estate, arts, philanthropy and activism. She turned business into a tool to uplift thousands of Black women economically and socially. Today, that legacy echoes in modern founders. Case in point: Beyoncé, through Parkwood and haircare line Cécred, and Rihanna with Fenty Beauty and Savage X Fenty, have built culturally resonant, global brands, generating wealth and shifting the zeitgeist of media narratives. Fenty as a brand, for instance, revolutionized inclusivity, but it also generated billions and reinvested in Black creatives.

A photograph of Sarah Breedlove driving a car; she was better known as Madam C.J. Walker, the first ... More woman to become a self-made millionaire in the United States.

Getty ImagesWhen Rihanna launched Fenty Beauty in 2017, she did so with a radical proposition that paid off: makeup for all skin tones. And like Walker, she revamped an entire market category in a way that made consumers pay attention and money. Fenty Beauty generated $100 million in sales within 40 days, ultimately valued at $2.8 billion, and Rihanna’s 50% stake made her a billionaire. Rihanna’s success stemmed from her distribution strategy: partnering with Sephora for premium placement while maintaining manufacturing control through Kendo Brands, which allowed her to capture both wholesale margins and retail premiums that traditional celebrity licensing deals surrender. More importantly, she proved that when Black entrepreneurs control distribution and narrative, they can capture value previously extracted by others.

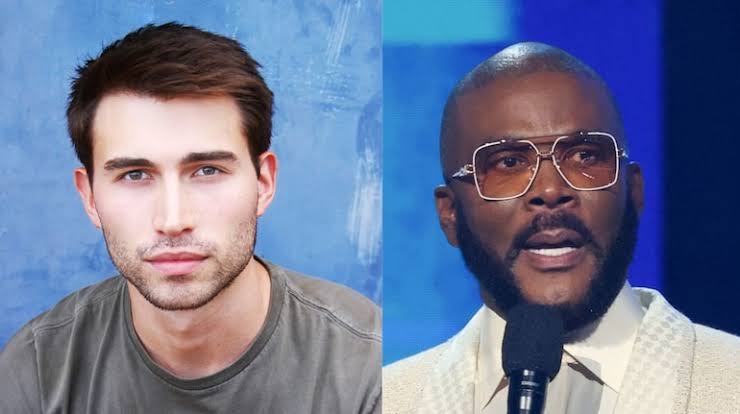

The pattern repeated with Beyoncé’s Ivy Park and now, Cécred, Issa Rae’s media empire and Tyler Perry’s studio complex. Each represents strategic integration—owning production, distribution and intellectual property rights rather than simply licensing talent for existing platforms. The next frontier lies at the intersection of ownership and innovation. Take the Liberated Capital Fund, part of Edgar Villanueva’s Decolonizing Wealth Project, which has deployed $20 million in reparative capital targeted at Black and Indigenous communities. Or consider VC: while Black entrepreneurs still receive under 1% of venture dollars, Black-led funds and accelerators are scaling—Harlem Capital, Backstage Capital, DVP’s accelerator—transforming ecosystem dynamics. Their intent isn’t charity, per se, as much as business. And it’s innovative business: a McKinsey study shows inclusive firms far outperform their peers.

Another engine is creator-economy ownership. Issa Rae, featured in TIME’s “Closers,” uses her platform to build cross-media brands, reinvesting capital back into community creatives. Aurora James’s Fifteen Percent Pledge moves $14 billion in revenue to Black-owned businesses, turning consumer attention into capital deployment. These strategies mirror Walker’s entrepreneurial DNA and the vertically integrated empire that she built, one that uplifted the Black community through economic infrastructure.

Part of Walker’s vertical integration included owning her zinc and sulfur supply chains, operating beauty schools that doubled as product training centers, and creating a commission structure that paid agents 25% more than domestic work, a move that turned what was economically necessary into entrepreneurial opportunity.

So what does Juneteenth teach the Forbes audience today?

The lessons for today's business leaders are as clear as they are urgent. Capital remains the prerequisite for sustainable freedom—emancipation without assets creates agency without options. Walker understood that wealth functions as generational infrastructure, a truth that modern Black founders are internalizing through equity structures and IP ownership. Most importantly, the data proves that ownership trumps charity every time. When Black entrepreneurs control distribution and narrative, they capture the market share and redefine entire categories.

Juneteenth does not solely represent a litany of injustice, nor is it a celebration for its own sake. It’s a lens: from 1865’s slow crawl toward freedom, through Madam Walker’s road-blocked rise, to today’s multi-billion-dollar empires of Beyoncé and Rihanna. It tells a story, one of liberation deferred; empowerment circumvented and wealth half-granted or, perhaps, half-seized.

The most profound lesson of Juneteenth isn’t about the past but about the future. Freedom delayed is opportunity denied, but freedom claimed is wealth created. Every day that systemic barriers prevent Black entrepreneurs from accessing capital is a day that superior returns remain uncaptured. Regardless, the arc continues. Black founders are building generational wealth through brand ownership, VC carve-outs, reparative capital and self-sovereign IP. As Madam C.J. Walker once did with her “Walker System,” today’s Black entrepreneurs are piecing together freedom in practice: culturally, economically and generationally. And that is the business of freedom.

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/Parents-JuneteenthCelebrationsAcrosstheUS-d58af61667c34d689e5986807a8f74c2.jpg)