Jugal Purohit

BBC Hindi, Delhi

Getty Images

Getty Images

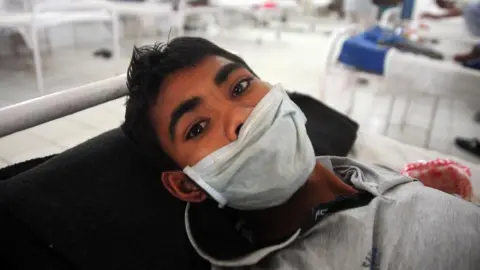

Atul Kumar (name changed) anxiously paced the corridor of a public hospital in India's capital Delhi.

A small-appliance mechanic, he was struggling to secure medicines for his 26-year-old daughter who suffers from drug-resistant tuberculosis (TB). Mr Kumar said his daughter needed 22 tablets of Monopas, an antibiotic used for treating TB, every day.

"In the past 18 months, I haven't received government-supplied medicine for even two full months," he told BBC Hindi in January, months before India's declared deadline to eliminate the infectious disease.

Forced to buy costly drugs from private pharmacies, Mr Kumar was drowning in debt. A week's supply cost 1,400 rupees ($16; £12), more than half his weekly income.

After the BBC raised the issue, authorities supplied the medicines Mr Kumar's daughter needed. Federal Health Secretary Punya Salila Srivastava said that the government usually acts quickly to fix medicine access issues when alerted.

Mr Kumar's daughter is one of millions of Indians suffering from tuberculosis, a bacterial disease that infects the lungs and is spread when the infected person coughs or sneezes.

India, home to 27% of the world's tuberculosis cases, sees two TB-related deaths every three minutes. India's TB burden has long been tied to poor case detection, underfunding and erratic drug supply.

Despite this grim reality, the country has set an ambitious goal. It aims to eliminate TB by the end of 2025, five years ahead of the global target set by the World Health Organization (WHO) and United Nations member states.

Elimination, as defined by the WHO, means cutting new TB cases by 80% and deaths by 90% compared with 2015 levels.

But visits to TB centres in Delhi and the eastern state of Odisha revealed troubling gaps in the government's TB programme.

In Odisha's Khordha district, around 30km (18.6 miles) from state capital Bhubaneshwar, 32-year-old day-labourer Kanhucharan Sahu is struggling to continue his two-year-old daughter's TB treatment, with government medicines unavailable for three months and private ones costing 1,500 rupees a month - an unbearable burden.

"We can't see her suffer anymore," he says, his voice breaking. "We even thought of abandoning her."

At Odisha's local TB office, officials promised to review Sahu's case, but a staffer admitted, "We rarely get the medicines we need, so we ration them."

Mr Sahu says he hasn't received the promised 1,000 rupees monthly support from the federal government and at the local TB office, officials admit to chronic shortages, leaving families like his adrift in a failing system.

Vijayalakshmi Routray, who runs the patient support group Sahyog, says medicine shortages are now routine, with government outlets often running dry. "How can we talk about ending TB with such gaps?" she asks.

There are other hurdles too - for example, changing treatment centres involves navigating complex bureaucracy, a barrier that often leads to missed doses and incomplete care. This poses a major hurdle for India's vast population of migrant workers.

At a hospital near Khordha, 50-year-old Babu Nayak, a sweeper who was diagnosed with TB in 2023, struggles to continue his treatment. He was regularly forced to travel 100km to his village for medicines as officials insisted he collect them from the original centre where he was diagnosed and first treated.

"It became too difficult," he says.

Unable to travel so often, Mr Nayak stopped taking the medication altogether.

"It was a mistake," he admitted, after contracting TB again last year and being hospitalised.

At his hospital, no TB specialist was available, highlighting another critical gap in India's fight: a shortage of frontline health workers.

The BBC shared its findings with the federal health ministry and officials in charge of the TB programme in Delhi and Odisha. There was no response despite repeated reminders.

A 2023 parliamentary report showed there were many vacant roles across all levels of the TB programme, affecting diagnosis, treatment and follow-up - especially in rural and underserved areas.

In 2018, when Prime Minister Narendra Modi brought forward India's TB elimination target to 2025, he cited the government's intensified efforts as a reason for optimism.

Two years later, the Covid pandemic disrupted TB elimination efforts globally, delaying diagnosis, diverting resources and pausing routine services. Medicine shortages, staff constraints and weakened patient monitoring have further widened the gap between ambition and reality.

Despite these challenges, India has made some progress.

Over the past decade, the country has reduced its tuberculosis-related mortality. Between 2015 and 2023, TB deaths declined from 28 to 22 per 100,000 people. This figure, however, is still high when compared with the global average which stands at 15.5.

The number of reported cases has gone up, which the government credits to its targeted outreach and screening programmes. In 2024, India recorded 2.6 million TB cases, up from 2.5 million in 2023.

Getty Images

Getty Images

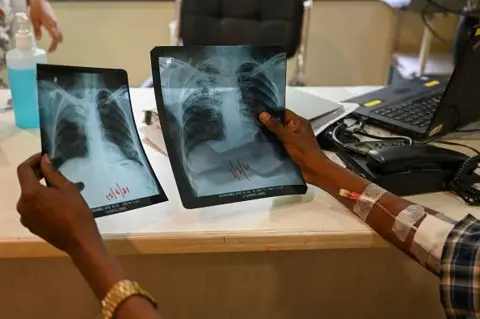

Federal Health Minister JP Nadda recently touted innovations like handheld X-ray devices as game-changers in expanding testing. But on the ground, the picture is less optimistic.

"I still see some patients come to me with reports of sputum (phlegm) smear microscopy for TB, a test which has a much lower detection rate as compared to genetic tests," says Dr Lancelot Pinto, a Mumbai-based epidemiologist.

Genetic tests, which includes RT-PCR machines - widely used to diagnose HIV, influenza and most recently, Covid-19 - and Nucleic Acid Amplification Testing, also examine the sputum sample but with greater sensitivity and in a shorter timeframe.

Besides, the tests can reveal whether the TB strain is drug-resistant or sensitive, something that microscopic testing can't do, Dr Pinto says.

The gap, he adds, stems not just from lack of awareness but from limited access to modern tests.

"Genetic testing is free at government hospitals but not uniformly available, with only a few states being able to provide it."

In May, Modi led a high-level review of India's TB elimination programme, reaffirming the country's commitment to defeating the disease.

But the official statement notably skipped mention of the 2025 deadline. Instead, it highlighted community-driven strategies - better sanitation, nutrition and social support for TB-affected families - as key to the fight.

The government has also prioritised better diagnosis, treatment and prevention at the core of its elimination strategy.

This approach mirrors the WHO's view of TB as a "disease of poverty". In its 2024 report, WHO chief Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus called it "the definitive disease of deprivation", noting how poverty, malnutrition and treatment costs trap patients in a vicious cycle. As India pushes toward its goal of eliminating the disease, deep health and social inequalities remain hurdles.

With just six months left until India's self-imposed deadline, new complications have emerged.

The fallout from US President Donald Trump's withdrawal from the WHO and suspension of USAID operations has raised concerns about future funding for global TB efforts. Since 1998, USAID has invested more than $140m to help diagnose and treat TB patients in India.

However, India's federal health secretary insists there is "no budgetary problem" anticipated.

Meanwhile, hope lies on the horizon. Sixteen TB vaccine candidates are currently in development across the world, with the WHO projecting potential availability within five years, pending successful trials.