Seabed mining is a new front in the U.S. versus the world

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners. Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy. A former banker, he edited the Wall Street Journal’s Heard on the Street column and wrote the Financial Times’s Lex column.

Another chunk of that crumbling edifice known as Pax Americana just fell into the sea — and sank right to the bottom. A would-be deep sea miner’s application for a U.S. license to exploit a patch of the Pacific seabed, triggered by an executive order from President Donald Trump, marks a fundamental break with the so-called rules-based order as it pertains to the deep. As with so much U.S. policy these days, the order identifies a real challenge but addresses it with all the subtlety of a depth charge.

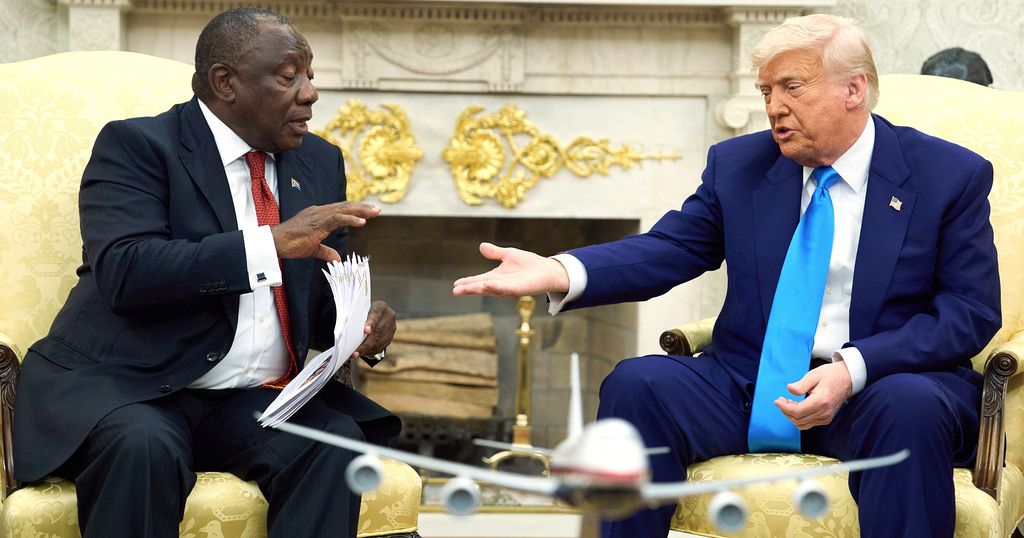

The Metals Company Inc., based in Canada, is seeking a license from the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration to exploit almost 10,000 square miles of the ocean floor beneath international waters between Mexico and Hawaii. It is a relative speck within the Clarion-Clipperton Zone, an area bigger than India hailed as a new Klondike for coveted metals. Trump signed an order last week directing NOAA to start dispensing such licenses with urgency, disregarding the role of the International Seabed Authority.

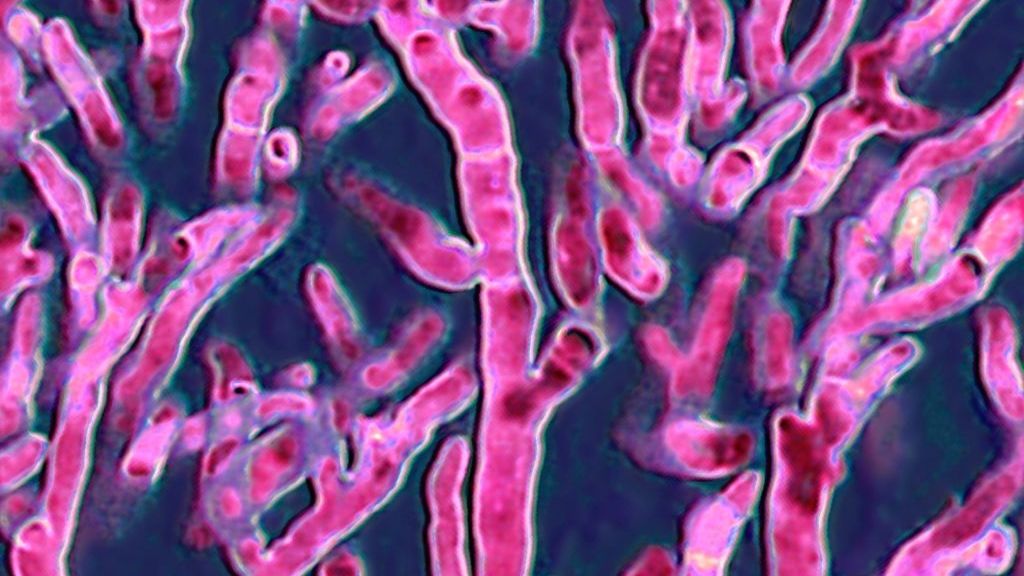

The concept of seabed mining, around for decades, has become more feasible as deep-sea technology has advanced and projections of demand for critical minerals to supply clean technology, defense and other applications have spiraled. Potential resources are dizzying. The ISA estimated in 2010 that the CCZ alone might contain three times the world’s terrestrial manganese resources, double its cobalt and almost as much nickel. To put that in perspective, the CCZ could provide enough materials for batteries to power up to 6.9 billion electric vehicles — more than four times the entire existing global passenger vehicle fleet — according to a recent study published by the Center for Strategic and International Studies.

The ISA is the international governing body for managing the seabed beyond national claims, established under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea. This has always rested on a fault line: The U.S. never ratified UNCLOS. Until recently, however, it essentially recognized its precepts as customary international law. That began to crack in late 2023, when former President Joe Biden’s administration unilaterally extended the U.S. outer continental shelf, particularly in the Arctic, where other countries such as Canada and Russia have instead submitted overlapping claims to the laborious UNCLOS process.

Now Trump has sanctioned an open rupture. The ISA has already granted 31 licenses in the CCZ, but for exploration only. Calls to establish rules for commercial development and issue licenses for that have been stalled for years, mostly on environmental grounds. The U.S. will now simply ignore the ISA and go its own way.

Trump is reminding us, once again, that international cooperation rests ultimately, and uneasily, on a foundation of national power. If major powers choose not to uphold agreements, then who enforces them? China, which holds five ISA licenses in the CCZ — the most of any country, which surely didn’t escape Trump’s notice — has objected and isn’t the only entity to do so.

That a company has eagerly grasped Trump’s invitation to plunge into a legal and geopolitical gray zone anyway, something that might normally deter private capital, speaks to two things. First, the ISA’s patent inability to move quickly enough as interest in seabed minerals has gathered pace. Second, perhaps a bet that Trump is effectively burying the paradigm of international cooperation on public goods. A similar shift is apparent in another harsh environment seen as a trove of mineral riches, the Arctic, where a vaunted diplomatic safe space has given way to outright division between Russia and NATO. Trump’s order presages "an entire system that has been developing for many years being circumvented while a competitor system is established," says Troy Bouffard, an Arctic security specialist at the University of Alaska Fairbanks.

As with the Arctic, the seabed’s potential riches tend to obscure the challenges involved. The case for exploiting the ocean floor encompasses everything from avoiding ecological and social damage from onshore mining to reviving domestic shipping to reducing the U.S. trade deficit. Indeed, TMC’s Chief Executive Gerard Barron laid out these points, and more besides, in testimony before a House Committee on Natural Resources hearing that was held — with striking coincidence — on the very same day the company made its application.

When it comes to the environmental impact, there are real risks to scooping up sediment and sending plumes of material, including metals, through the water column. On the other hand, all mining involves trade-offs and the risks must be balanced against the damage done in places like Congo and Indonesia, as well as the broad harm of climate change if the critical minerals to make clean technologies are in short supply.

That concept of trade-offs undercuts the narrative of seabed mining being a magic bullet. Commercial viability is inherently unknown: No one has actually mined the seabed which, as you might expect, is an unforgiving place. The pressure at the bottom of the CCZ is about 400-500 times that at sea level, and the West Coast, with support and infrastructure, would be five days sailing away. There’s a reason U.S. oil activity has boomed in west Texas and atrophied on Alaska’s North Slope.

Trump’s order also carries his hallmark of a bold splash masking deficiencies and contradictions. The most glaring is that the same administration making a statement of intent about boosting critical minerals supply is also intent on undercutting one of the biggest customers for that supply, green energy.

Beyond this, Gracelin Baskaran, a director at CSIS, notes a lack of anything in the order pertaining to maritime security, despite having effectively fired the starting gun for an international free-for-all that could see Chinese autonomous vehicles roaming the seabed close to Hawaii. For all its protests, China’s desire to maintain a grip on critical mineral supply chains and clean technologies means it may secretly welcome Washington providing tacit permission to dispense with the niceties of the ISA — another consequence of unilateral action. The abyssal plain, largely a desert of darkness, is taking on the characteristics of the jungle.

This column reflects the personal views of the author and does not necessarily reflect the opinion of the editorial board or Bloomberg LP and its owners. Liam Denning is a Bloomberg Opinion columnist covering energy. A former banker, he edited the Wall Street Journal’s Heard on the Street column and wrote the Financial Times’s Lex column.