BMC Medical Education volume 25, Article number: 227 (2025) Cite this article

Retaining anatomical knowledge is crucial for safe and effective medical practice, yet many medical graduates struggle to apply this knowledge in clinical settings over time. This study aimed to evaluate and compare the retention of gross anatomy and clinical anatomy knowledge among medical graduates in Sudan.

A cross-sectional study was conducted in a sample of 385 medical graduates from various Sudanese universities, estimated using the Cochrane formula. The participants completed a self-administered questionnaire assessing their knowledge of gross and clinical anatomy, as well as demographic and educational factors. The data were analyzed via descriptive statistics, paired t-tests, and ANOVA.

Clinical anatomy knowledge was significantly better retained (mean score: 68.39%) than gross anatomy knowledge was (mean score: 45.35%). The retention of gross anatomy is influenced by academic background, with integrated and hybrid learning approaches showing better outcomes than traditional methods do. In contrast, clinical anatomy retention was more consistent across demographic factors but varied by speciality, with emergency medicine, general practice, surgery and radiology showing the highest retention levels.

Clinical anatomy is retained more effectively due to its frequent application in practice, whereas gross anatomy requires greater integration with clinical relevance to enhance retention. The study recommends medical curricula that merge gross and clinical anatomy through active learning strategies and continuous education to improve long-term retention and clinical competency.

Anatomy serves as a cornerstone in medical education, providing the essential knowledge required for effective clinical practice and enabling healthcare professionals to accurately diagnose and treat a variety of medical conditions [1, 2]. The retention of anatomical knowledge is critical for ensuring safe and effective clinical practice, yet evidence suggests that many graduates struggle to retain and apply this information over time [3].

The distinction between gross anatomy, which focuses on the structural organization of the human body, and clinical anatomy, which applies this knowledge in diagnosis and treatment, is particularly significant. Although these areas are often taught separately, their integration is crucial for a comprehensive understanding of medicine [4].

Previous studies explored anatomical knowledge retention and reported that both undergraduate students from medical sciences, such as medicine and nursing, and physicians presented declining anatomical knowledge [5,6,7]. Studies have identified several factors that contribute to this problem, including an overemphasis on pure memorization rather than conceptual understanding, a lack of clinical context in teaching, and limited opportunities for practical application [2, 8].

There are significant variations in anatomical curricula and their integration of clinical experience in basic sciences courses, including the integration of dissection, virtual reality, radiology, and clinical cases at the beginning of medical school [9,10,11,12]. However, there is a lack of research on how different teaching methods affect the retention of anatomical knowledge during clinical practice.

Sudan currently has over 30 medical schools, with programmes varying widely in their degree of curricular integration, available infrastructure for anatomy education (such as cadaveric dissection facilities), and emphasis on clinical exposure. While some schools have adopted integrated or hybrid curricula, others continue to follow predominantly traditional, discipline-based structures. Resources for anatomy education, including dissection labs and radiological facilities, differ markedly across institutions, potentially influencing the quality of anatomy teaching.

Despite these variations, there is a common concern regarding anatomy retention post-graduation. Based on existing literature [12] and anecdotal observations in Sudanese medical schools, we hypothesise that: [1] clinical anatomy knowledge is retained more effectively than gross anatomy knowledge due to frequent clinical application; [2] graduates from integrated curricula will demonstrate better retention of gross anatomy than those from traditional programmes; and [3] participants’ time since graduation, speciality choice, and experienced teaching methods will significantly influence knowledge retention.

The study aims to identify differences in knowledge retention between the two courses and the factors that contribute to these discrepancies. The findings provide valuable insights into how anatomy education can be enhanced to better prepare graduates for the clinical challenges they face, ultimately leading to improved medical training and patient care.

This cross-sectional study was conducted to assess and compare the retention of gross anatomy and clinical anatomy among medical college graduates in Sudan. The study was conducted across multiple medical schools in Sudan, with participants recruited through alumni networks and medical graduate associations. Data were collected between June and August 2024.

The study included medical graduates who had completed both gross anatomy and clinical anatomy courses and had completed less than 5 years since graduation. Graduates who did not complete the required anatomy courses or were involved in specialized anatomy teaching roles were excluded. The sample size was calculated via the Cochrane formula to include 385 medical graduates recruited conveniently via social media invitations facilitated by alumni groups and networks. Multiple announcements were posted in social media groups and alumni mailing lists to invite participation.

A structured questionnaire was developed for this study by a senior anatomist and contained the following sections: (1) participant characteristics, such as age, gender (male or female, reflecting biological sex), and field of practice; (2) teaching methods during medical school, including traditional subject-based learning and problem-based learning; (3) gross anatomy questions, comprising 10 multiple-choice questions; (4) clinical anatomy questions, comprising 10 multiple-choice questions; and (5) self-rated knowledge of gross anatomy and clinical anatomy (supplementary). The questionnaire was validated by three senior anatomists at the faculty of medicine, National University, Sudan, and tested for reliability in a pilot of 38 (10%), revealing a Cronbach’s alpha value of 0.72 for gross anatomy questions and 0.77 for clinical anatomy questions, indicating high reliability.

The data were analyzed via SPSS software version 26. Descriptive statistics, such as the means and standard deviations for continuous variables and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables, were calculated. Comparisons between retention of gross anatomy and clinical anatomy were performed via paired t tests, and comparisons of retention across different participant characteristics were performed via ANOVA.

The study included 385 participants with a mean age of 27.35 years (SD = 2.10), ranging from 22 to 35 years. Among the participants, 67% were female, and 33% were male. The most common medical specialties were internal medicine (22.6%), surgery (22.3%), and general practice (14.5%), while 8.6% had not yet determined their specialty (Table 1).

In terms of position, the majority were general practitioners (50.4%), followed by interns (30.4%) and residents (12.2%), and a small percentage were not working (7%). With respect to the time since graduation, 44.2% had graduated three years ago, 22.9% four years ago, and 15.1% had graduated two years ago (Table 1).

The participants reported a variety of educational backgrounds, with 49.6% having undergone traditional academic programs, 41% having undergone integrated programs, and 9.4% having undergone hybrid programs. When asked about their anatomy teaching methods during undergraduate study, 53% reported traditional lectures and labs, 28.3% experienced a hybrid approach, and 18.7% participated in problem-based learning (PBL). The preferred method of learning anatomy was clinical anatomy (63.1%) rather than gross anatomy (36.9%) (Table 1).

Detailed responses on gross anatomy and clinical anatomy retention are shown in Tables 2 and 3 below. Overall, gross anatomy retention had a mean score of 45.35 (SD = 23.56), whereas clinical anatomy retention was significantly greater, with a mean score of 68.39 (SD = 22.63) (p < 0.001) (Table 4).

For gross anatomy retention, there was significant variation based on the type of academic background (F = 7.377, p = 0.001) and the length of time since graduation (F = 7.544, p < 0.001). Compared with those in traditional programs, medical professionals who have undergone integrated or hybrid academic programs tend to have better gross anatomy retention. Similarly, gross anatomy retention improves with time since graduation, particularly in individuals who graduated more than 5 years ago (Table 5).

In contrast, clinical anatomy retention was less influenced by academic background but was significantly different across medical specialties (F = 4.043, p < 0.001). Practitioners in fields such as emergency medicine, general practice, surgery, and radiology tend to retain clinical anatomy knowledge better than those in fields such as anesthesiology or obstetrics and gynecology. Interestingly, the analysis indicated that clinical anatomy retention remained fairly consistent across genders (F = 0.806, p = 0.491) and types of academic programs (F = 0.363, p = 0.696) (Table 5).

Figure 1 shows that participants’ self-rated knowledge of gross anatomy displayed variability across the seven assessed anatomical systems. For the musculoskeletal system, nervous system, and head and neck anatomy, the majority of participants rated their knowledge as “poor,” with 42.1%, 43.1%, and 43.6%, respectively, reflecting a lack of confidence in these critical areas. The urogenital system also had a notable portion of participants (30.1%) rating their knowledge as “poor,” indicating moderate levels of uncertainty in this area. On the other hand, participants demonstrated greater confidence in their knowledge of the cardiovascular system and gastrointestinal system, with 47.5% and 48.3%, respectively, rating their knowledge as “excellent.” This finding indicates increased confidence in these clinically relevant systems. Moreover, 38.2% of the participants rated their knowledge of the respiratory system as “excellent”.

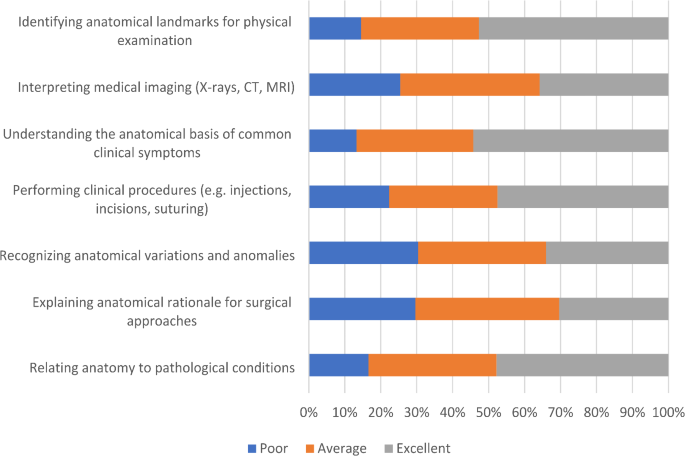

In terms of clinical anatomy, participants expressed greater confidence overall in applying anatomical concepts to clinical scenarios. The majority rated their knowledge as “excellent” in areas such as identifying anatomical landmarks for physical examination (52.7%), understanding the anatomical basis of common clinical symptoms (54.3%), performing clinical procedures such as injections and suturing (47.5%), and relating anatomy to pathological conditions (47.8%). However, the participants expressed less confidence in certain areas. The interpretation of medical imaging received a lower rating, with 38.7% rating their knowledge as “average.” Recognizing anatomical variations and anomalies also posed challenges, with 35.6% rating their knowledge as “average.” Similarly, the anatomical rationale for surgical approaches was rated as “average” by 40.0% of the participants (Fig. 2).

The retention of anatomical knowledge is a critical component of medical education, serving as the foundation for safe and effective clinical practice. Without a firm understanding of human anatomy, healthcare professionals may struggle to diagnose and treat patients effectively, leading to potential risks in clinical care. However, studies have shown that many medical graduates face challenges in retaining and applying anatomical knowledge, particularly as they transition from theoretical learning to practical applications in their medical careers [2, 3].

The significance of this issue lies in the growing concern that graduates, despite excelling in anatomy during their academic years, may lose crucial aspects of this knowledge over time if it is not continuously reinforced or applied. As medical education continues to evolve, integrating anatomy with clinical practice is becoming increasingly important to ensure that future healthcare professionals are adequately prepared to meet the demands of patient care [4]. Therefore, we evaluated and compared the retention of gross anatomy and clinical anatomy knowledge among medical graduates to answer the following questions:

The study revealed that clinical anatomy knowledge is significantly better retained than gross anatomy knowledge, with a mean retention score of 68.39% for clinical anatomy knowledge and 45.35% for gross anatomy knowledge. This result is consistent with the literature, as studies have shown that basic knowledge, including anatomical knowledge, follows a gradual trajectory over time as students advance in medical school and further after graduation [5,6,7, 13]. The self-reported application of clinical anatomy —whether through physical exams, imaging interpretation, or operative procedures—in daily practice may contribute to its better retention among graduates, as frequent clinical use can reinforce knowledge through repeated exposure [14]. However, this study relied on participants’ self-assessment of how often they employ anatomical knowledge, which may conflate confidence with actual usage. This underscores the need for caution in attributing higher retention solely to perceived daily application. Gross anatomy, which can appear more theoretical when divorced from immediate clinical contexts, may require more intentional integration with clinical scenarios to foster long-term retention.

The retention of gross anatomy knowledge varies based on academic background, with graduates from integrated or hybrid academic programs demonstrating better retention than those from traditional programs. For example, traditional programs teach gross anatomy as a subject in which students are taught about different structures, their relationships, and anatomical concepts; integrated and hybrid programs, on the other hand, are those in which students study the clinical implications of identifying these structures in the clinical setting, such as clinical case scenarios. Thus, better retention of gross anatomy knowledge among students who were exposed to this integration is expected [12], as the presence of a clinical context is one of the most effective methods to aid knowledge memorization and retention, according to Drake et al. [3].

In this study, “integration” refers specifically to curricula that embed clinical case scenarios into anatomy teaching. Other approaches—such as linking macro- and micro-anatomy—do not necessarily shift a school from “traditional” to “integrated” or “hybrid.” For example, in one traditional program, gross anatomy is taught over the first two years by focusing on memorization (e.g., identifying which vessel passes behind the duodenum). In an integrated model, that same artery is presented as commonly implicated in peptic ulcer perforation, making it more clinically relevant and thus more memorable.

Time since graduation was another factor, with individuals who graduated five years ago showing better retention than recent graduates did. This study’s cross-sectional design precludes definitive conclusions about how time independently influences retention. While it is plausible that cumulative clinical exposure over several years reinforces anatomical knowledge, there may also be confounding factors—such as selective job roles, further training, or self-motivation to keep knowledge updated—that are not fully accounted for. A longitudinal or prospective design tracking the same cohort over time would more accurately capture how knowledge evolves with increasing clinical experience.

The retention of gross anatomy is also system-specific, with students retaining knowledge of the gastrointestinal and respiratory systems better than more complex systems such as the nervous system and head and neck anatomy [6]. This is similar to our findings in the self-rated anatomical knowledge section; graduates rated themselves the lowest in the head and neck, nervous system, and musculoskeletal modules, whereas they were more confident in other systems, such as the cardiovascular, respiratory, and gastrointestinal systems.

The study revealed that medical professionals in fields such as emergency medicine, general practice surgery, and radiology retain more than 70% of their clinical anatomy knowledge, which is better than that of professionals in other specialities. This reflects the impact of frequent use in clinical settings. As Hołda et al. (2019) and Antipova et al. (2024) suggested, the application of anatomical knowledge in diagnosing and treating patients helps reinforce learning [1, 5]. Specialities that require the regular application of clinical anatomy benefit from improved retention. Moreover, fields that rely less on anatomical knowledge may not reinforce it as strongly, leading to lower retention rates. This finding supports Elsiddig et al. (2016), who also noted better retention among medical professionals who applied anatomy regularly in practice [14].

This study also supports the frequent and repetitive application of anatomical knowledge. The participants were more confident in their ability to apply their knowledge to frequent tasks, such as physical examination and suturing, during their practice than were less common participants, such as recognizing anatomical variations and anomalies. Kooloos et al. (2020) emphasized that repetition of anatomical knowledge of any kind is beneficial for long-term retention [15].

Teaching methods play a significant role in anatomy retention. Graduates who experienced problem-based learning (PBL) or hybrid teaching methods retained clinical anatomy knowledge better than those who were taught through traditional lectures. This finding supports findings by Meo, (2013) Azer et al., 2013), and Kasarla et al., (2023), who highlighted that PBL fosters deeper understanding and practical application of knowledge [16,17,18]. Additionally, modern tools such as virtual reality can enhance learning [9], but traditional methods such as cadaveric dissection are still vital for developing a strong understanding of anatomy [10].

The results highlight the need for more integration of gross and clinical anatomy, emphasizing the clinical relevance of anatomical concepts and structures to ensure better retention and application. Zhang et al. (2023) advocated incorporating clinical scenarios and real-life applications into the teaching of gross anatomy [12]. The success of combining traditional methods with newer approaches, such as virtual reality, PBL, peer teaching, and flipped classrooms, to improve retention supports the need for a multifaceted teaching approach [16, 19, 20]. Curricula should always strive to make education a more effective process; this means incorporating innovative methods and adding fun to the teaching process while adhering to learning objectives and maintaining scientific integrity.

The cross-sectional design of this study provides only a snapshot of anatomy knowledge retention, making it impossible to determine causality or confirm long-term trends. Additionally, recall bias may be present since participants rely on memory to answer knowledge-based questions. Moreover, the use of social media and alumni networks for recruitment may introduce selection bias if more academically motivated graduates were more inclined to respond. These limitations restrict the generalizability of our findings to all Sudanese medical graduates or those in different regions.

Medical curricula should further integrate gross and clinical anatomy via active learning strategies—such as problem-based learning, dissection, simulations, and digital tools—to reinforce real-world clinical relevance. Longitudinal studies could clarify how speciality choice and clinical exposure affect retention, while regular refresher training (e.g., workshops and structured revisits) would help maintain anatomical knowledge. This multifaceted approach—coupled with ongoing curriculum evaluation—can optimize both immediate learning gains and long-term retention of gross and clinical anatomy.

This study revealed that clinical anatomy is better retained than gross anatomy among medical graduates, largely because of its frequent application in clinical practice. The retention of gross anatomy, on the other hand, is influenced by factors such as academic background, teaching methods, and time since graduation, with integrated and hybrid learning approaches proving more effective. To address this disparity, this study emphasizes the need for curricula that integrate gross anatomy with clinical applications, utilizing active learning strategies such as problem-based learning and modern technological tools.

Data analyzed in this study is available upon reasonable request from the corresponding author.

We would like to thank MedStat Research Centre for technical support in preparing and revising this manuscript.

This research received no fund or grant from any governmental or non-governmental organization.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the Research Ethical Committee of the Faculty of Graduate Studies and Scientific Research, National University, Sudan.

Informed consent was obtained from all participants before their involvement in the study.

Data were collected confidentially and anonymously, no identifying information was collected, and secure data management practices were followed throughout the research process.

Not applicable.

Not applicable.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Saeed, M., Ahmed, L., AbdAlla, E. et al. Retention of gross and clinical anatomy knowledge among medical graduates in Sudan: a comparative study. BMC Med Educ 25, 227 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-06832-5

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12909-025-06832-5