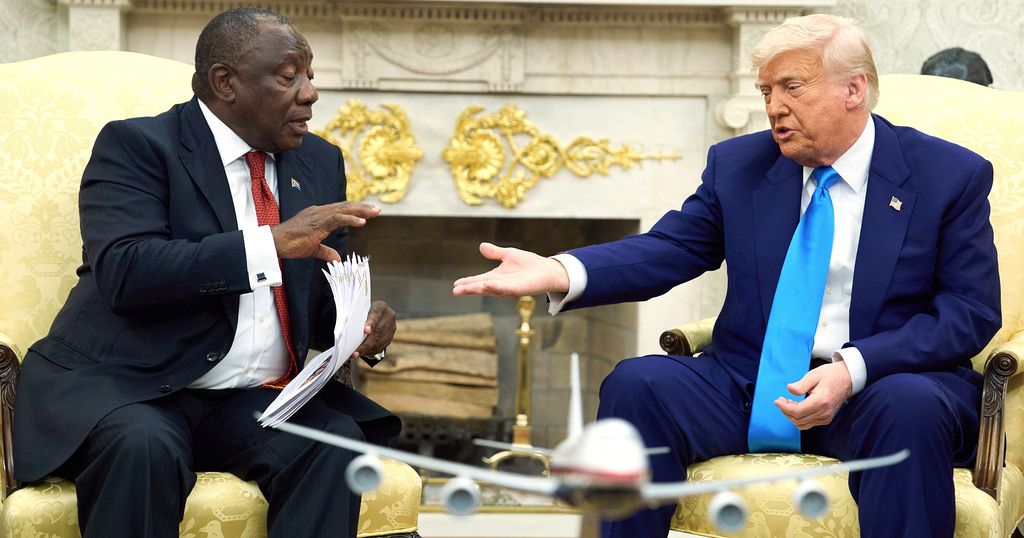

When the UK’s prime minister Keir Starmer visited the White House in February, he charmed Donald Trump with an invitation from the British King Charles, playing to the president’s notorious vanity. But South Africa doesn’t have quite the same cache of soft power to draw from. The best the country’s president Cyril Ramaphosa could bring when he visited the White House today was two white South African golfing legends much admired by Trump, Ernie Els and Retief Goosen.

Trump received the golfers gratefully, showering them with praise. Then, he turned on Ramaphosa.

As the two presidents took questions from the press, the lights dimmed and Ramaphosa found himself watching prepared videos of the leaders of South Africa’s two populist parties, the Economic Freedom Fighters and the Umkhonto we Sizwe Party, chanting slogans about killing white farmers. Next came an image of a thousand white crosses, a memorial to the dead.

It was reminiscent of the demeaning treatment Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky received when he visited the White House. Only this time, Trump’s ambush was far more clearly choreographed, and thus somewhat less unstylish.

Ramaphosa had a piece of bait dangled before his nose. He was made to watch what Trump took to be evidence that the South African government was presiding over the slaughter of white Afrikaners. Ramaphosa did not take the bait. He held his composure and mustered a skillful response. But he hardly came out well.

The show Trump had staged only allowed for two possible stories. One was that a genocide of white farmers was taking place. The other was that crime was out of control in South Africa and that the country needed help. Ramaphosa told the latter story. In the circumstances, it was the best he could do.

And it is surely right.

More than 26,000 people are murdered in South Africa every year. For a country of 64 million people that is simply staggering. Its per capita murder rate is nearly nine times higher than the United States’s and seven times higher than Kenya’s.

Who are these 26,000 people?

The best studies available show that the majority are Black and mixed-race men between the ages of 15 and 44, and that most are either un- or under-employed. Being murdered is thus an experience largely monopolised by the young and the poor.

And precisely because they are poor, their violent deaths neither threaten political stability at home nor make news abroad. In a grim, horrible sense, their corpses are weightless on the international political scales.

But the young and the poor are not the only victims of awful crimes. South Africa is violent enough for nastiness to stream out of the ghettos and into the suburbs, and, indeed, onto the farms. There are many middle-class experiences of horror in South Africa, and unlike the poor, what happens to middle-class people is weighty enough to be packaged and sold to audiences abroad.

The false narrative of a genocide of white people in South Africa is thus truly perverse; the murders of whites are the visible crust under which lies a veritable carnage of young Black men.

That is more or less what Ramaphosa and his delegation tried to tell Trump. We do not need your opprobrium, they said; we need your help. Our police stations need your technology to fight crime; our people need your economy to invest in ours so that fewer young men are violently idle and more are employed.

And to be fair to Ramaphosa, the chorus he conducted was deft. He got his agriculture minister, John Steenhuizen, a white man and the leader of a large opposition party, to speak eloquently on these matters. The billionaire South African businessman, Johann Rupert, spoke forcefully too. Between them they presented a unified, multi-racial front. They pointed out that South Africa was a constitutional democracy in which extremist parties were free to provoke; that the state had not confiscated anyone’s land since the advent of democracy; that the idea of a racial genocide was grievously mistaken.

But for all that, Ramaphosa’s performance was painful to watch. For he was reduced to saying that he presided over a country that had lost control over itself and required assistance. And not just from any country, but from the United States, which made the humiliation all the more painful.

South Africa’s relationship with the United States is ever so fraught. For many decades now, the country has been saturated in American culture. Its highway system and its suburban sprawl are inspired by post-war America. Its daytime television soap operas and its prime-time dramas are templates of American originals. In Cape Town’s ghettos, street gangs distinguish between themselves via rival allegiances to East Coast and West Coast rap.

A country at the tip of a continent thousands of miles from U.S. shores, South Africa is testimony to the power and the reach of the cultural hegemony America has exercised over the world. And that renders South Africa’s relationship to America brittle, testy, and complicated. To be the one to go to the White House saying that we are drowning and need your help is not the way any South African president would want to be remembered.

But given the cards Ramaphosa was dealt, it was the best hand he could play.