Pete Rose saga is a story for our times

The Pete Rose saga is a story for our times — messy, complicated, fueled by competing passions, with a plot line that includes a president whose presence sometimes seems inescapable.

It's a tale that is about much more than whether or not the deceased baseball great gets into his sport's hall of fame.

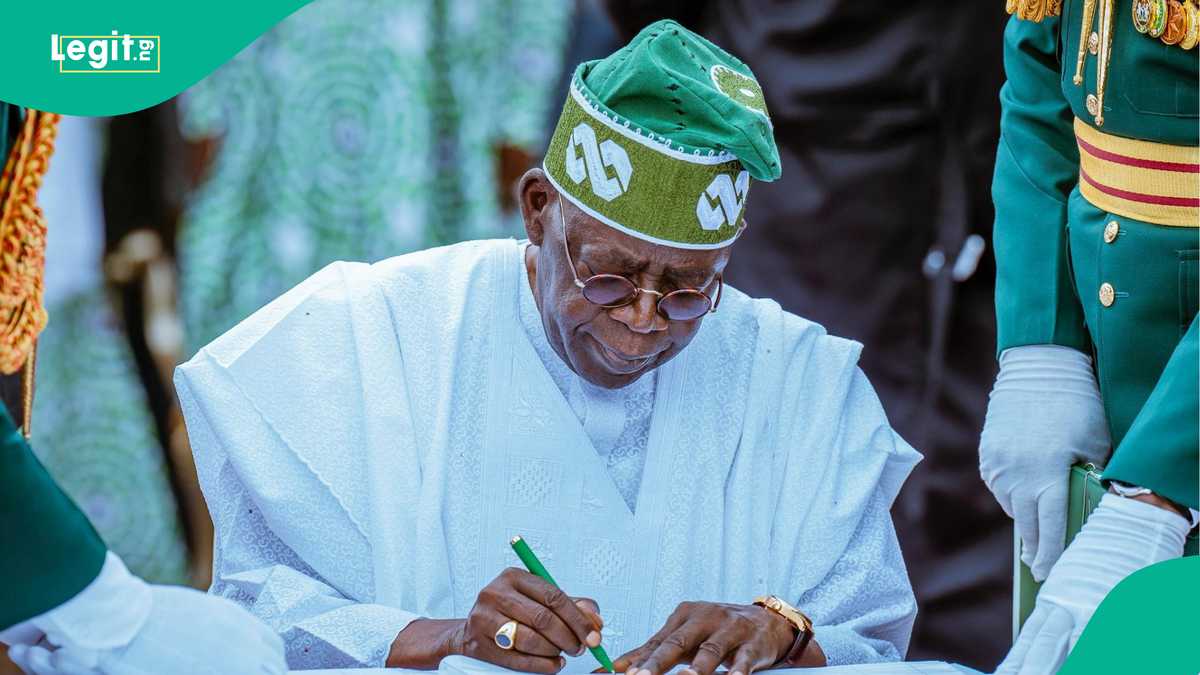

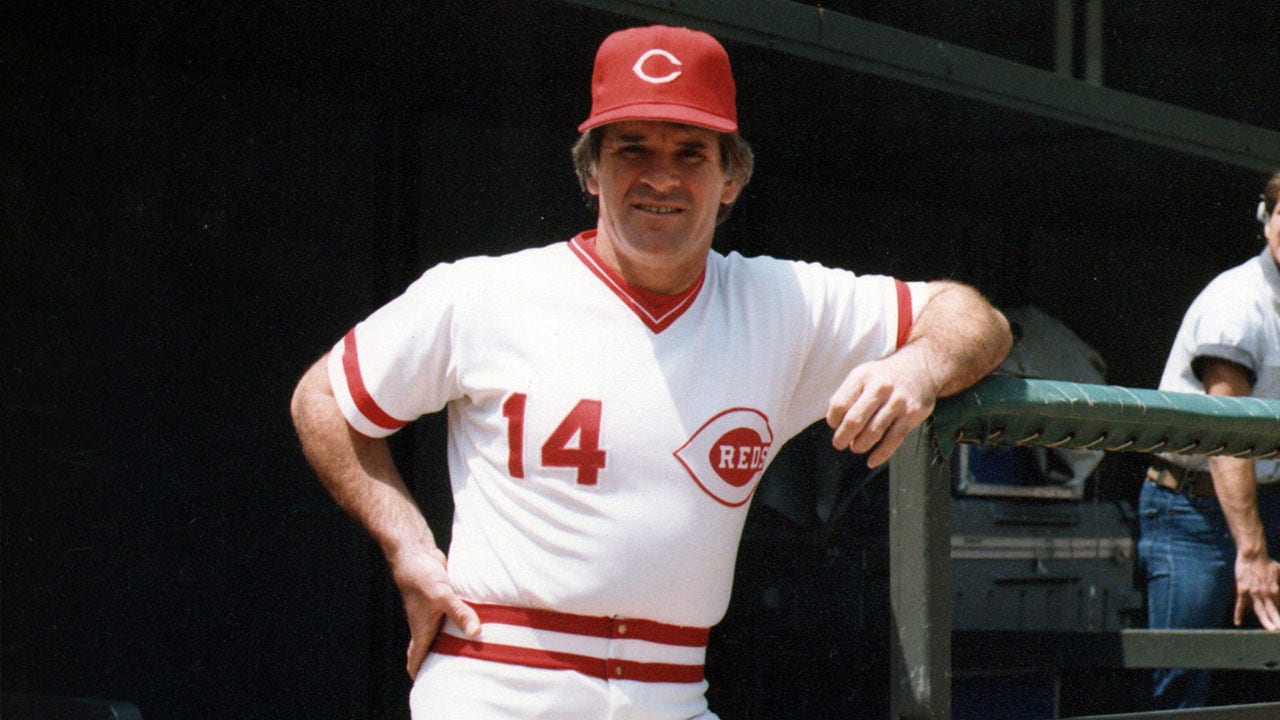

The bare facts are simply stated. Rose, who famously agreed to a permanent ban from baseball in 1989 for betting on the game, was reinstated Tuesday by Commissioner Rob Manfred, eight months after Rose died last September. That makes Rose eligible for enshrinement in Cooperstown, which is still by no means guaranteed and requires analysis and votes by two committees.

Now, to be clear, baseball is a private enterprise. It can make its own rules and its own exceptions. But it also markets itself as the national pastime, and has at times demanded special treatment because of that status, which gives it a public sheen that requires some deference to public opinion and mores. Both of those are fractured when it comes to Rose. How do you weigh the different criteria for enshrinement as enumerated by the Baseball Hall of Fame — namely, that the baseball writers who vote consider among other things playing ability and integrity? Rose aces the first but largely flunks the second.

You might also be exercised by the politics. Manfred met in December with Rose's oldest daughter and his former attorney, who made the case for his reinstatement. No announcement followed. On April 16, Manfred met with President Donald Trump, a prominent all-caps backer of Rose, and Charlie Hustle's status was among the topics. Less than one month later, Manfred reversed his long-held position and brought Rose back into the fold. Did Manfred fear public ridicule from Trump if he did not reinstate Rose? To what degree was his decision linked to his push for a direct-to-consumer streaming service for Major League Baseball, at a time when the federal government is scrutinizing the migration to streaming by pro sports in general?

Other shades of gray tint the Rose chronicle.

Manfred's justification that "a person no longer with us cannot represent a threat to the integrity of the game" might not be true — accepting someone who violated a cardinal rule of baseball by betting on it, who served five months in prison for tax evasion, and who was credibly accused of having a sexual relationship with a girl under 16 in the 1970s, might indeed be a blot on the sport's integrity — but it was a shrewd positioning.

It tapped into the current zeitgeist, a kind of moral ambiguity under which everyone seems to get a pass or a pardon. Bad behavior often has a disturbing lack of consequences. Rules are malleable, for public figures and private citizens. Many of us know certain things are wrong but we do them anyway and rationalize — "I was running late for my appointment, so I had to do 55 in a 25-mph zone."

The Rose decision could be read as an acknowledgment that right and wrong are not as clear-cut as they once were. Especially in baseball, one of many pro sports now awash in gambling — from the naming rights deals FanDuel has with broadcast partners of several teams to the money MLB rakes in from ads promoting gambling companies. In bringing back Rose, Manfred also reinstated the eight players banned in the 1919 Black Sox gambling scandal. From Rose, it's a slippery slope to baseball's steroid users, who thus far have been refused enshrinement.

After Manfred's decision, San Diego Padres manager Mike Shildt said that "grace is a really important thing. Clearly, they made mistakes, and now they’re getting some grace."

Grace and redemption indeed are good and powerful things, but so are standards.

One thing, at least, has not changed: Wisdom is found in how we set the balance.

Columnist Michael Dobie's opinions are his own.

Michael Dobie is a member of the Newsday editorial board.