BMC Nutrition volume 11, Article number: 133 (2025) Cite this article

European welfare states are facing a growing demand for charitable food aid in the current economic and political climate. While efforts have been made to enhance the dignity of food aid and address limited access, it is crucial to consider the impact of food aid on health, given the detrimental consequences of inadequate nutrition across the lifespan. This study aims to assess the nutritional contribution of food packages distributed by food aid organizations in Barcelona (Spain) to the needs of four types of households. The data were collected biweekly for two months from three food aid organizations in Barcelona. Nutritional information was retrieved from the product label and food composition databases and compared to the European Food Safety Authority’s dietary reference values for four types of households. Results indicate that nutrient adequacy depends on the organization’s food provisioning capacity and household size, with larger households facing higher food insecurity risks. One-person households lacked protein, calcium, zinc, and vitamin D, while households with two or more people failed to meet most micronutrient needs. Additionally, the packages often exceeded recommendations for fat and sodium. These findings underscore the vulnerability of food aid recipients to nutritional insufficiency, particularly in households with children who may experience compromised growth and development. Limited resources and high demand generate food packages that do not meet users’ nutritional needs. This research in Spain emphasizes the urgency for policymakers to intervene in food aid organizations and guarantee the supply of food that meets minimum nutrient requirements.

Food insecurity is a concealed phenomenon in Europe [1], despite nearly 8% of the population experiencing it to a moderate or severe extent [2]. In the region, food insecurity is predominantly the consequence of impaired access to food driven by insufficient economic resources [3].

Food insecure populations are at a higher risk of health issues due to lower dietary diversity, micronutrient deficiencies, and excessive intake of cheap ultraprocessed foods [4,5,6,7,8]. Moreover, food insecurity encompasses significant psychological and social impacts due to the lack of autonomy and authority over one’s food choices [9, 10].

In Europe, food assistance schemes coexist with national and regional welfare and social protection measures, including minimum income schemes, unemployment benefits, and child-related allowances [11, 12]. Emergency devices such as food banks and other in-kind food aid like soup-kitchens are amongst the most frequently used to alleviate severe food deprivation. Regional instruments, although with different developments between countries such as the Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived (FEAD) and the current European Social Fund Plus (ESF+), have been implemented to provide food and non-material assistance to EU’s most vulnerable population such as low-income households, single-parent families, older adults living alone, and undocumented migrants [13]. However, there is evidence that their capacity to reverse food insecurity is limited, especially when set against the fundamentals of an adequate diet [14,15,16,17]. Globally, food banks demonstrate a restricted potential to provide nutrient-dense foods in sufficient amounts, especially from fresh-foods [14], and to meet individual needs, including cultural and health preferences [18, 19].

In Europe, the dietary and nutritional contribution of food aid to the needs of recipients has been seldom investigated. In France, Castetbon et al. showed how half of the 1446 subjects of a study targeting food aid users in four urban French zones fulfilled the French recommendations for starchy foods, meat, fish and eggs, and over a quarter met the recommendations for seafood, while less than 2% ate the recommended amount of fruits and vegetables [7]. In addition, obesity, hypertension, anemia and folate and vitamin D deficiency were considerably prevalent [7]. In Portugal, Nogueira and co-authors found that while the redistributed food did not meet the recommended daily intakes for all nutrients [20], it still provided over 70% of most nutrients. Based on data from four European cities in Belgium, Finland, Hungary, and Spain, Hermans et al. evaluated the food composition and the monetary value of food aid packages provided by twelve organizations [13] and showed that the composition of the food aid basket is not aligned with the recommendations for healthy eating.

To our knowledge, the nutrition contribution of food parcels has not been investigated in Spain, even though it has significant rates of severe material and social deprivation (8.3% vs. 6.3 in EU-27) [21], with a high share of the socially excluded population saying to have experienced hunger (11.7%) [22]. Particularly, according to data from Moragues-Faus & Magaña-González [23], 13,3% of Spanish households suffer from food insecurity (6.235.900 people), 1,4% increase in respect to prevalence before the COVID outbreak. In 2020, in Catalonia, 3.2% of the population received food aid [21]. Data from the previous study of Moragues-Faus et al. (2022) estimates that on average 8% of Barcelona citizens experience food insecurity, but in some districts such as Ciutat Vella food insecurity is as high as 23% [23].

This research aims to assess how the food aid packages provided in three food aid centers in Barcelona contribute to meet the nutrient needs of different household types and to identify the main food sources for the selected nutrients.

Food aid in Spain operates within a diverse framework involving both public and private entities, with various responses aimed at combating food insecurity. While newer and alternative approaches have emerged to transform conventional aid models by addressing the broader social and cultural dimensions of food insecurity, such as using vouchers, cards, community kitchens, or social gardens [24], traditional responses remain central. These traditional methods, exemplified by food banks and soup kitchens, have historically provided crucial support in meeting immediate food needs during crises.

These traditional initiatives predominantly focus on addressing the biological dimension of food insecurity, providing emergency relief to those in need. The Spanish Federation of Food Banks (FESBAL) serves as a key organization coordinating the efforts of numerous food banks across the country, collaborating with associated distribution and delivery organizations to ensure efficient food distribution to recipients [24]. The sustenance procured by Spanish food banks originates from diverse channels, encompassing contributions from individuals, enterprises, and governmental entities. Donations from private citizens and community collectives predominantly comprise non-perishable essentials, such as canned goods, grains, and pasta. Corporate contributors, spanning supermarkets, food producers, and wholesalers, often furnish surplus or unsold foodstuffs, which, while still consumable, would otherwise be at risk of disposal. It has been reported that since 2021, a year after the “anti-food waste” law from Generalitat de Catalunya, food donations have almost doubled [25]. Furthermore, governmental bodies may allocate financial resources or direct provisions of food-to-food banks, either as part of established social welfare initiatives or in response to exigencies [26].

In the 2014–2020 period, the FEAD constituted one of the most important sources of provisioning for food banks. In this period, Spain received more than 3.800 million euro from it, which were considerably supplemented because of the COVID crisis. In Spain, the management of this process has been overseen by the Spanish Guarantee Fund for Agricultural Supplies (FEGA), tasked with, among other functions, procuring food through a public tendering process and appointing Associated Distribution Organizations (OAD) through public resolution. Subsequently, these OADs, including FESBAL and Cruz Roja, distributed the food to Associated Delivery Organizations (OAR), numbering over 5400 throughout Spain, which directly delivered the food to the intended recipients.

The Regulation (EU) 2021/1060 [27], issued by the European Parliament and Council on June 24, 2021, abolished the previous FEAD Program and incorporated its activities into the new FSE+. In the implementation of this regulation at the national level, the Territorial Council for Social Services and the System for Autonomy and Care for Dependency unanimously agreed on December 15, 2021, to manage thematic concentration to combat material deprivation through a unified national program, albeit with autonomous implementation. In addition to autonomous management, the significant change stemmed from the implementation model, transitioning from direct food distribution to indirect provision through cards or vouchers, in accordance with EU regulations. This change aims to offer comprehensive support while respecting the dignity and rights of beneficiaries, promoting autonomy, and normalizing assistance.

Because food aid is not strictly governmentally centralized nor regulated, there exist a wide diversity of models of action by the different organizations who provide it, determining eligibility criteria, characteristics of the food aid, logistics, etc. In this context, public institutions, especially local ones, play a significant role in coordinating some responses directly implemented through policies targeting food insecurity, while others rely on actions by private organizations and voluntary groups within the Third Sector [28].

In the last decades, several steps have been taken by the city of Barcelona to move forward towards healthier, fairer, and more sustainable food systems [29]. Despite the traditional lack of competences of local governments in this area, a wide range of policies and actions have been developed, with an outstanding implication of stakeholders from the quadruple helix: science, policy, industry, and society. Examples of such actions include the Food Charter of the Metropolitan Region, the Network for the Right to Adequate Food [30] or the Sustainable Food Strategy 2030 [31]. In this context, considerable effort is being made to establish common procedures, criteria, and requirements, for instance, by trying to unify food aid to avoid duplications by streamlining resources, with an increasing trend of centers requesting social services referrals for resource rationalization. However, the landscape remains fragmented and insufficiently cohesive.

The exploratory study with a case study design was conducted in February-May 2022 in the context of the EUSocialCIT H2020 project [32]. The aim was to assess the nutrient contribution of food aid packages provided in three food aid centers in Barcelona to different household types and identify the main food sources for the selected nutrients.

Three food aid centers were selected from a list (n = 78) that had been compiled to conduct a previous online survey on food aid in eight European countries [33]. Organizations eligible for participation in the EUSocialCIT project had to meet specific criteria, including providing regular food aid at least once a month, employing the distribution method of food parcels (versus other forms of food aid like cooked meals), having food aid as the main activity, and distributing food for free to vulnerable individuals. Given the known variability in food aid practices — both between and within organizations — and the documented heterogeneity in distribution models across Europe [33, 34], a case study design was chosen to reflect the diversity of food aid as it functions in practice. The selection of three distinct organizations was intended not to produce directly comparable data, but to capture and document the structural variability of food assistance in the urban context of Barcelona. This variability is considered an essential aspect of the system under study.

All organizations agreed to participate voluntarily and signed a collaboration agreement after receiving information of the purposes of the study.

During the study period, each food aid organization was visited four times to record the content of the food aid packages distributed. Moreover, during the initial visit, structured interviews were conducted with the head or a knowledgeable volunteer at food distribution points to obtain fundamental information about their history, operations, and clientele. An excerpt of this information is presented in Table 1, full results can be consulted in [13].

Food Aid Centre 1 (FAC1) was a parish-driven center founded in 1973, with all the workforce being volunteers, FAC2 started in 2010 and is managed by a neighborhood association with both volunteers and a hired coordinator, and FAC3 was established by a catholic charity in 2014 and is currently run by volunteers. In 2021, FAC1 had approximately 95 people registered to receive food aid, whereas FAC2 and FAC3 had roughly 30 and 700, respectively. Food recipients were individuals (and their families) unable to meet basic needs, as assessed by the municipal social services, who referred recipients to the food aid organizations. Although we did not specifically collect data about the users’ profile for this research, we assume that it is aligned with previous research indicating that demand for food aid is higher among households with dependent children with no income, low work intensity, or in which main source of income are unemployment benefits or social assistance [33]. Carrillo-Alvarez et al., found in a sample of food aid recipients in Barcelona that the monthly median expenditure on food was 14.1€ (IQR ± 30€) per person of the household [35].

Food was provided on appointment once per month in FAC1 and FAC3, and every 2 weeks in FAC2. In the three centers, the food distributed was acquired through public and private donations and FEAD surpluses. Due to COVID restrictions, the three centers provided food aid through fixed packages, although FAC2 and FAC3 allowed limited freedom of choice beforehand. Food packages were the same regardless of household size except in FAC3, which provided 6 types of packages to meet the needs of households with up to 6 members. The primary obstacles facing FAC1 and FAC2 in customizing food parcels stem from limited resource allocation, encompassing both financial and human capital. Constrained human resources render tailoring parcels to individual household sizes impractical, prompting charitable organizations to adopt standardized approaches for equitable distribution. FAC1 offered Muslim and non-Muslim food packages. For comparability reasons, this article only presents results from the non-Muslim packages.

Data collection was conducted at four different time points, with two weeks in between. A picture was taken from each food item. In the case of packaged foods, a picture was taken from the front and back of the packaging to clearly identify the product and the nutritional information. Additionally, the following information was retrieved using an Excel spreadsheet: product name, brand name, volume(g/l), package type (fresh, frozen, canned), FEAD product(yes/no).

After completing the fieldwork, the food nutritional composition was defined per 100 g of product using food labels and food composition databases (FCDB). For fresh food (fruit, vegetables, and certain types of meat), all values were retrieved from the FCDB. For packed foods, food labels were used to determine the energy content and those nutrients that are mandatory to be declared in the food label (total carbohydrates, sugars, fats, proteins, and salt). For the remaining nutrients (fiber, calcium, iron, magnesium, zinc, vitamin B12, folate, vitamin A, C, and D) data was completed using FCDBs. The food selected to complete the nutritional information was the one that best matched the product description, ensuring that the macronutrient content was also equivalent. In this regard, the CESNID [36] FCDB was used, and if a specific food product or nutrient was not available, the McCance & Widdowson (2021) and USDA (2016) databases were used [37, 38]. If a specific product was not identified in any of the FCDBs, another food with similar nutritional characteristics was selected. Nutritional content was assessed based on net weights, calculated using the edible portion factors provided in the CESNID database. When a specific food item was not available, a suitable proxy from the same database was used. The resulting nutritional assessment was based on the net weights of whole foods, therefore dietary supplements were not considered. Salt as a condiment was excluded from the analysis to only account for the sodium naturally found in food and/or added due to food transformation, considering that it is difficult to establish how long a package lasts. The duration of the other foods in the parcel was estimated considering the frequency of delivery. All this information was registered for each type of package centers provided.

The theoretical nutritional requirements of each household were determined by adding up the Dietary Reference Values (DRV) of the different individuals on the selected household types: single adult man (30-65y), adult couple (30-65y), adult woman (30-65y) with a girl (10y) and adult couple(30-65y) with a girl(10y) and a boy(14y) [39]. The choice of family types responds to Spain’s most prevalent household distribution [40]. Previous research has investigated the nutritional quality of food parcels at the individual level [18], and applying this approach enables an assessment of how well food aid centres can tailor their contents to meet the needs of recipient households.

The contribution to the theoretical nutritional requirements per household was assessed by comparing the content of the food parcels, considering the frequency of distribution, with the DRV of the selected types of households as set by the EFSA DRVs. Details of the selected nutrients and their respective DRVs per individual analysed can be found in the supplementary material. It is important to note that the use of the 100% DRV threshold in our analysis does not imply an assumption that recipients have no other food on the given day or that 100% of their nutrient needs should be exclusively met by the food parcel. Rather this analysis allows us to gauge the nutritional impact within daily requirements, pinpointing gaps and evaluating potential cost savings for recipient families. This method also aids in identifying specific nutrients or food items that warrant targeted attention in social assistance programs, nutrition education, and related interventions.

The amount of total carbohydrates and fat was transformed to the corresponding percentage of energy that the food parcels provided concerning the average requirement (AR) of energy for each individual type as defined by the EFSA for a physical activity level of 1.6. For carbohydrates, we compared the amount present in the food parcel with the lower limit of the AR(45%), while for fat, we used the upper limit(35%). Protein DRVs are set as g/kg, therefore, to avoid making assumptions about the weight of the recipients, the number of calories provided by the proteins in the food parcels was set against the number of calories not provided by carbohydrates and fat(20%). Salt(g) was converted into sodium(mg) using the conversion factor 396. No database estimates free sugars, and hence we followed the methodology used in the Danish national food consumption survey where sugars from specific food groups are classified as free sugars (sweets, cakes, soft drinks, desserts, and breakfast cereals) [41, 42]. Sugars from flavored dairies, vegetable sources, and jams account for half of the total content to deduce lactose and fructose contribution [43].

The contribution of the food parcels to the nutritional requirements of each household is expressed as the percentage of the daily needs of all members. Results display the average contribution of the four data collection points and the value for each date. Since FAC3 was the only centre distributing food aid depending on household size, each household type from FAC3 is paired with the specific size of the food parcel, and in the case of FAC1 and FAC2, the single-size food parcel is used for all household types.

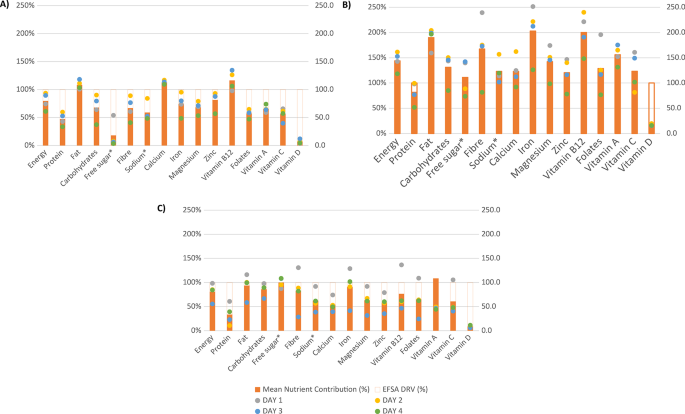

Figure 1 shows the contribution of the food parcels to the DRV of an adult man. The food parcels in FAC1 and FAC3 consistently felt short of energy recommendations, while they were exceeded in FAC2 (average of 144%). FAC1 and FAC3 averaged around 80% of the recommendations. FAC2 was the only center meeting carbohydrates DRV, except for day 4. Two out of the four days from FAC2 and FAC3 exceeded the upper threshold for free sugar. FAC1 provided 18% of the upper limit, reflecting the low amount of sugar sources supplied compared to FAC2 and FAC3(average net weight of sugary foods: 25 g vs. 259 g and 107 g). Fiber DRVs were only met by FAC2 three of the four days, and FAC3 one day. Across all centers pulses were the main source of fiber, despite the variation of the amount across data collection days. Vegetables and enriched foods like cocoa powder allowed to meet the fiber recommendations in FAC2. However, caution is warranted due to the large amount of cocoa provided (2.4 kg over 2.5 months), which translates to a daily portion exceeding 30 g, far above recommended and typical serving sizes. All baskets were generally high in fat, surpassing the upper limit of daily recommendations except on days 3 and 4 from FAC3, whose fat content was correct. Protein recommendations were not met by none of the analyzed baskets.

Regarding micronutrients, FAC2 aligned with all micronutrient DRVs except for vitamin D and sodium. FAC2’s sodium content exceeded the limit by 23%, mainly from processed protein sources (35–61% to overall sodium content). This is explained by the fact that only one of the 4–6 food items provided each day was not processed. Over the 4 days, 8 different protein sources were supplied. Of these, only eggs were unprocessed and the remaining processed which were chicken burgers, soy-based meat analogue, canned tuna, chicken sausages, canned sardines, vegan chorizo, and chicken pâté. Dairy products were the main source of calcium across centers and those that provided at least two glasses of milk per day(400 ml) met EFSA DRVs for this mineral. Therefore, FAC1 and FAC2 met the DRVs by 113% and 123%, respectively, whereas FAC3 only covered 54% of the needs. Iron DRVs were met throughout all days in FAC2 in the range of 126–252% based on the contribution of plant-based and animal proteins. FAC1 and FAC3 failed to reach the recommendations due to the lower supply of animal protein. This pattern was also observed with magnesium and zinc since FAC2 was the only one that met the EFSA recommendations. FAC2 met 142% and 120% of magnesium and zinc DRVs, respectively, whereas the remaining two were deficient throughout all days. The main sources of these minerals were starches and animal protein when content was higher(mainly in FAC2). Finally, from the group of vitamins, folates and vitamin C DRVs were only met by the food parcels of FAC2(average: 129 − 123%, respectively). The DRV for vitamin C was met up to 161% on day 1, but not on day 2. FAC1 and FAC3, on average, did not reach two-thirds of EFSA DRVs for those vitamins. Legumes were one of the main sources of folates, followed by vegetables which explain the differences between centers. As it has been described above, significant variations exist concerning the content of vegetables in the food parcels. Being vegetables and fruits the main sources of vitamin C, the shortage of this vitamin could be explained by the low amounts of these foods in FAC1 and FAC3. FAC2 and FAC3, on average, were sufficient in providing vitamin A(156 − 108%, respectively). However, the average alignment of FAC3 is due to an outlier from day 1 in which 1 kg of carrots was provided in the food parcel, and thus recommendations were met by 293%, whereas the remaining days did so by only 44-49%. Vitamin B12 daily needs were ensured in FAC1 and FAC2(average: 112% and 200%, respectively), whereas FAC3 only provided 76% of the DRV. Contribution to this vitamin is aligned with the amount of animal protein provided, therefore explaining FAC2 large contributions (up to 240% on day 2).

The Supplementary Material contains detailed nutritional data for each food aid center, including both daily assessments and center-specific averages.

Contribution of food aid packages to adult man nutritional requirements. Panel A corresponds to FAC1, panel B corresponds to FAC2, and panel C corresponds to FAC3

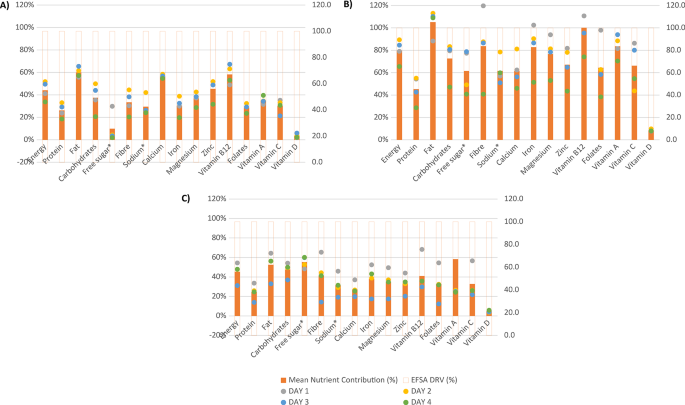

The nutritional analysis of food aid baskets for an adult couple (Fig. 2) posed greater challenges in meeting nutrient recommendations compared to a single adult. None of the centers met energy DRVs, with FAC1 and FAC3 averaging 44% and 45% of EFSA DRVs, and FAC2 reaching 80%. Carbohydrate provision was insufficient across centers. Free sugars aligned with recommendations, with FAC1 providing the lowest amount.

No center met fiber DRV, except for day 1 from FAC2, which supplied 146% due to higher legume, vegetable, and fiber-fortified cocoa powder content. The remaining centers provided 33–41% of fiber DRV. FAC2’s parcels were generally excessive in fat, aligning with recommendations only on day 1 (88%). FAC1’s fat content fell within EFSA DRV, while FAC3 didn’t meet the lower threshold. Protein content was deficient across centers, with FAC1, FAC2, and FAC3 providing, on average, 26%, 45%, and 25% of the DRV, respectively.

Analyzing micronutrients, FAC2 generally provided a higher amount, although adequacy was only reached for vitamin B12. In contrast to the single adult profile, sodium content didn’t exceed upper limits for any center or day. FAC2’s mean calcium content averaged 61%, higher than FAC1 (56%) and FAC3 (27%). For magnesium, FAC2 performed better, with a mean contribution to EFSA DRVs of 77%, compared to 37% and 35% from FAC1 and FAC3, respectively. FAC2 also excelled in zinc content, providing 67% of EFSA DRVs, while FAC1 and FAC3 provided 45% and 33%, respectively. The higher zinc levels in FAC2 may be attributed to more zinc-rich foods like legumes, dairy, and animal protein. Iron recommendations were met only on the first day of FAC2 (by 102%), with a mean contribution remaining at 83%. FAC1 and FAC3 provided about one-third of daily iron recommendations.

Vitamin B12 requirements were met exclusively by FAC2, averaging 100%. FAC1 and FAC3 provided only 58% and 41% of this vitamin, respectively. Other vitamin contents were insufficient, with vitamin A provided in higher amounts, followed by folates and vitamin C. FAC2 provided 84% of vitamin A DRV, while FAC3 and FAC1 provided 58% and 35%, respectively. FAC2 supplied two-thirds of the recommendations for folates and vitamin C, while FAC3 and FAC1 contributed roughly one-third. Vitamin D was insufficient across centers, with contributions ranging from 3% in FAC1 to 8% in FAC3.

Contribution of food aid packages to the nutritional requirements of an adult man and woman aged 30-65y. Panel A corresponds to FAC1, panel B corresponds to FAC2, and panel C corresponds to FAC3

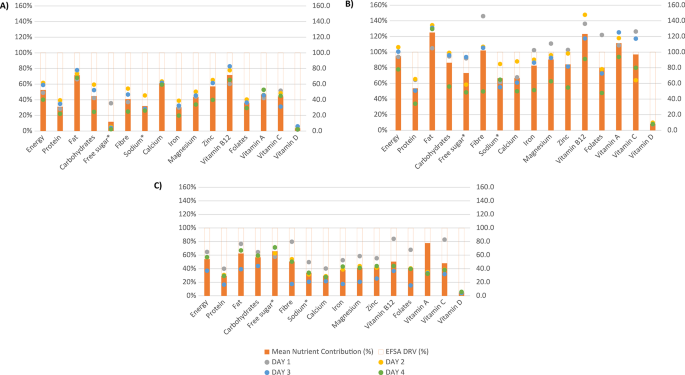

Similarly to the adult couple household, food parcels intended for a woman living with a 10-year-old girl consistently lacked sufficient nutrients across all centers (Fig. 3). Energy adequacy remained suboptimal, with only days 2 and 3 from FAC2 meeting recommendations, averaging at 95%. FAC1 and FAC3 provided 52% and 54% of the required energy, respectively. Although FAC2 had the highest carbohydrate content, it still fell short of the minimum threshold on all days. FAC3 and FAC1 met carbohydrate recommendations on average, at 57% and 45%, respectively. Free sugar content remained below recommended maximum levels, with FAC2 and FAC3 having the highest levels. FAC2 met fiber DRV on three data collection days, averaging at 102%, while the other centers provided approximately half of the recommended values. FAC2 consistently exceeded EFSA DRVs for fat content by 25%, while FAC1 and FAC3 adhered to recommendations, falling within the 20–35% range of daily calorie intake. Protein contributions were insufficient in all three centers (FAC 1: 31%; FAC2: 54%; FAC3: 29%).

None of the food parcels met the DRVs for the analyzed minerals, though FAC2 generally provided higher amounts. Sodium content remained within daily allowances for all centers. FAC2 contributed two-thirds of the daily allowable sodium content, while FAC1 and FAC3 accounted for roughly one-third. Calcium recommendations were better met in centers providing more dairy, namely FAC1 and FAC2, but still only reached 61-67% of EFSA DRVs. Regarding iron, FAC2 covered 83% of the recommended intake, while FAC1 and FAC3 only reached 30–38%, respectively. Magnesium and zinc content from FAC2 nearly met mean DRVs (90%-84%), while the other centers provided 43 − 41% of magnesium and 57%-42% of zinc needs (FAC1-FAC3, respectively).

In terms of vitamins, FAC2 was the only center that provided adequate average amounts of vitamin B12 and A (123%-111%). However, on day four, both nutrients were insufficient (91-94%). FAC2 met folate and vitamin C DRVs by 80-97%, respectively, with full compliance on day 1. FAC1 and FAC3 fell 64%-59% below folate recommendations and 56%-52% below vitamin C DRV. As seen in previous food parcels, all centers provided less than 10% of EFSA DRVs for vitamin D.

Contribution of food aid packages to the nutritional requirements of an adult woman (30-65y) and a 10y girl. Panel A corresponds to FAC1, panel B corresponds to FAC2, and panel C corresponds to FAC3

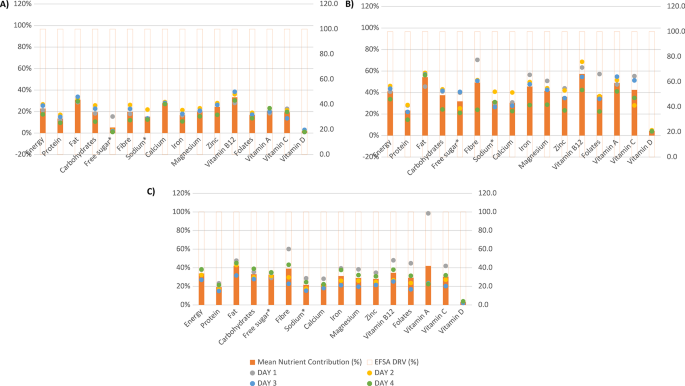

As depicted in Fig. 4, food parcels designed for a household consisting of an adult couple and two siblings (a 10-year-old girl and a 14-year-old boy) consistently fell short in meeting essential nutrients, despite efforts by FAC3 to adjust the parcels for household size. Most of the recommended nutrient levels were not met, often remaining below 50%. Like previous households, FAC2 generally provided higher nutrient quantities, but it was still insufficient. On average, FAC2 supplied 41% of the recommended energy intake, while FAC1 and FAC3 provided 23% and 34%, respectively. Carbohydrate intake from FAC2 and FAC3 met approximately one-third of the minimum recommendation, whereas FAC1 provided only 19%. Free sugar content was within acceptable dietary limits. Fiber intake reached only half of the recommended values in FAC2, and 20–39% in FAC1-FAC3.

Unlike previous households, the fat content did not meet the lower DRV threshold, and protein recommendations were also not met. FAC1 had the lowest protein content at 13%, while FAC3 contributed 19% to protein requirements for larger households. Sodium content in the packages aligned with EFSA DRVs. Iron and magnesium DRVs were better satisfied in FAC2 (46% and 42%, respectively) and FAC3 (31% and 29%, respectively). Calcium and magnesium contributions were highest in FAC3 but still 72–76% below recommended levels.

Regarding vitamins, the contribution of food parcels ranged from 2% for vitamin D in FAC1 to 57% for vitamin B12 in FAC2. Notably, FAC2 did not meet vitamin B12 recommendations in any of the analyzed days, a deviation from previous scenarios. FAC1 and FAC3 provided approximately one-third of the DRV for this vitamin. Folate intake posed challenges for all centers, with FAC1 providing the lowest amount (17%), followed by FAC3 (29%), and FAC2 (38%).

Contribution of food aid packages to the nutritional requirements of an adult woman and man (30-65y) with a 10y girl and 14y boy. Panel A corresponds to FAC1, panel B corresponds to FAC2, and panel C corresponds to FAC3

This paper reports a study to assess the nutritional contribution of food parcels provided by three food aid organizations in Barcelona, Spain. Although this type of research has proliferated in the last few years in other contexts [14, 18, 44,45,46,47], this is, to our knowledge, the first in our country.

Results reveal substantial variability between and within centers, reflected in differing nutritional coverage and food variations across collection dates. For instance, the FAC3 food parcel for an adult varied from almost 5000 g of boiled legumes on day 1 to 380 g on day 3. These differences stem from the nature and functioning arrangements of the food aid organizations, and from the fact that the food aid provided in Spain is not governmentally regulated and heavily reliant on donations and food surpluses [48,49,50]. This phenomenon is however not exclusive of Spain. In different European contexts, food aid has been described as part of the new charity economy, where surplus or expired goods from the primary economy are sent to a secondary system, where they are distributed for free or sold at discounted rates by volunteers or low-wage workers [48, 51]. Moreover, in-kind food aid has strong links with agrifood businesses, who, as part of their corporate social responsibility agenda, often offer or sell surplus food with favorable conditions to charities and food banks [52]. The FEAD fund, based on food purchases, was conceived to guarantee a stable provision of food aid, but extension of the execution period due to the COVID pandemic has created shortages during this final stage before it is integrated into the FSE+ [53].

Importantly, the heterogeneity observed across food parcels — in terms of size, frequency, and content — is not merely a methodological constraint, but a reflection of the structural realities of food assistance in Spain. Rather than aiming to compare centres as if they operated under standardized conditions, this study sought to capture and make visible the variability inherent in food aid provision. This diversity stems from the heavy reliance on donations and surplus redistribution, which are known to fluctuate throughout the year and are shaped by economic, logistical, and policy-related factors [33, 52]. The unpredictability of food parcels —both in quantity and nutritional composition — reflects the lived experiences of recipients and providers, and is a central feature of the current system. Attempting to standardize or control these variables would have undermined the ecological validity of the study. Instead, documenting this variation allows for a more accurate understanding of how systemic factors influence the nutritional adequacy of food aid and highlights the broader challenges associated with ensuring consistent, equitable, and health-promoting food assistance.

Indeed, fluctuations of food provided on different days convey a sizable impact both in nutritional and psychological terms. Previous studies have highlighted that food bank users exhibit proficiency in food budgeting [54, 55]. However, the irregularity of what is received hinders household organization, potentially leading to inadequate diets and persistent concerns about food. This ongoing worry about food scarcity is a critical component of food insecurity [56] as indicated by established measurement scales [57,58,59].

It has been consistently described that in the absence of adequate child-sensitive social protection, households with children may face greater difficulties to make ends meet and are at a greater risk of limited income growth [60], material deprivation [61], food insecurity [23], and, as supported by our results, nutritional inadequacy [62,63,64]. Even in the food aid distribution center in which the content of the food parcels varied by household size, nutritional adequacy decreased with increased members in the household. Children in food-insecure households are at a greater risk of encountering biopsychosocial developmental hazards [65,66,67], likely impairing their future trajectories.

Our results align with previous research exploring the nutritional adequacy of food assistance. Following the conclusions from Oldroyd and co-authors [18], although the provision of food parcels enables vulnerable populations to access unaffordable food, food insecurity is likely to remain. Recipients are at a greater risk of shortage for protein, zinc, folates, vitamin D, and fiber, which is in line with the literature [4,5,6,7,8]. This tendency is driven by the relative lack of fresh fruit, vegetables, and animal-source foods, paired with a considerable supply of sugary sources, ultra-processed foods, and prepared meals. Even though we did not include them in the nutritional analysis, FAC2 food parcels contained multivitamin supplements that could potentially contribute to facing these deficiencies. However, the efficacy of such supplements is not well established [68, 69], and discretionary use is not recommended [70]. Protein and vitamin D were the nutrients that were consistently lacking across food aid centers and data collection days. It is crucial to note that the EFSA DRV for proteins is expressed in g/kg of body weight, rather than as a percentage. However, in our theoretical exercise, we set protein theoretical requirements at 20% of the total energy intake, as we could not establish a specific body weight. In baskets containing a significant amount of energy (i.e., 3700 kcal/day), such as those from FAC2, using percentages may lead to a misleading perception of low protein content. The mean weight of adult men in Spain is 84 kg [71] who would meet the 0,83 g/day EFSA’s Population Reference Intake (PRI) indicator with around 69 g of protein per day. The protein content in the baskets varied from 54 to 183 g per day, resulting in some baskets, particularly those from FAC2, surpassing the required protein intake. In contrast, others fell significantly below the recommended levels. Moreover, evidence suggests that while the 0,83 g/day target prevents deficiencies, optimal health outcomes in adults would require intakes in the range of at least 1.2 to 1.6 g/(kg·day) of high-quality protein [72], which would emphasize the shortage of protein in the baskets. Additionally, most sources of protein in the analyzed food parcels were processed foods (i.e., canned fish, all types of processed meat) which were responsible for the high sodium content.

Food parcels, while culturally adapted for Muslim recipients, generally lacked consideration for specific health conditions, including allergies or intolerances, despite evidence pointing out that it can effectively improve situations like obesity, diabetes, or HIV [73,74,75], and dietary preferences such as vegetarianism, even though they are a cornerstone element of the food experience [76]. The omission of personalized dietary accommodations may have significant repercussions for recipients, contributing to diet-related health inequalities [77,78,79].

Overall, our results show that while the food provided plays a crucial role for recipients, the organization of food aid in Spain constrains its effectiveness in alleviating both food and nutrition insecurity by not being able to provide a stable, standardized, healthy food parcel that is adapted to the size and characteristics of the household. Studies in other countries report that while food bank users are grateful for the help they receive, they are also aware of their limitations concerning the quantity, quality, selection, and provisioning of food [45, 80,81,82].

The question of what the most adequate form of food assistance remains in the debate [83,84,85]. Indeed, in the turn from FEAD to FSE+, where the in-kind food provided by the fund is to be swift by prepaid credit cards, the question of how food parcels contribute to meet the nutritional theoretical requirements of food aid users may seem outdated. In our sample, the FEAD share of the food aid packages fluctuated between 3.3% and 18.1% [13]. However, food donations and food aid packages are not likely to disappear. As observed in other settings [86], cash and in-kind assistance are complementary rather than competing methods of delivering assistance, in that they have differential characteristics that may be more suitable for distinct situations of the recipients.

The limited sample and time frame constitute the greatest limitation of this research, which further research should expand. Although we registered four days of food provision, we tried to counteract short-term coverage by selecting days from different weeks in order to better capture the supply variance over time. Likewise, this is a theoretical exercise estimating the nutritional contribution of the food parcels to the theoretical needs of prototype households, as per the EFSA DRV, assuming no food wastage and an equal food distribution among household members. However, future research should pair the nutritional analysis with real intake information and health outcomes of the different members of the households, as well as investigate whether households’ food provision is guaranteed through other sources (i.e., money transfers, family support…). This approach would allow a greater comprehension of the utilization dimension of food insecurity. Additionally, accounting for nutrient bioavailability would provide additional depth to this understanding. However, our study provides the first analysis of the nutritional contribution of food parcels in Spain, which can stimulate social action, governmental awareness and involvement, political debate, and further research on the topic. In addition, in our analysis it is assumed that no food wastage.

In summary, this study assessed the nutritional value of food parcels from three food aid organizations in Barcelona. Results showed considerable variability in content, both between centers and different collection days. This variability arises from operational differences and a lack of government regulation in the Spanish food aid system impacting nutrition and psychological well-being, especially in households with children. Nutrient analysis highlighted the challenges food aid organizations face in meeting nutritional recommendations, which intensify with larger household sizes, putting children at greater risk of food insecurity’s adverse effects. The study also emphasized the absence of special health considerations and dietary preferences for recipients. Despite limitations, this research exposes food aid system shortcomings, calling for comprehensive solutions through policy changes and stakeholder collaboration. It advances the understanding of food aid’s nutritional impact and underscores the need for further research and action.

Data will be available upon request to the corresponding author at the following email address [email protected].

- DRV:

-

Dietary Reference Values

- EFSA:

-

European Food Safety Authority

- FAC:

-

Food Aid Centre; FCDB

- FCDB:

-

Food Composition Databases

- FEAD:

-

Fund for European Aid to the Most Deprived

- FEGA:

-

Guarantee Fund for Agricultural Supplies

- FESBAL:

-

Spanish Federation of Food Banks

- FSE+:

-

European Social Fund Plus

- OAD:

-

Associated Distribution Organizations

- OAR:

-

Associated Delivery Organizations

The authors want to express their gratitude for the participation of the studied organizations, which made the data collection possible.

European Union’ Horizon 2020 research and innovation programme (GA 870978).

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki. It is part of the Horizon 2020 EUSOCIALCIT project (ref. nº 870978), whose alignment with ethical principles was periodically reviewed by the designated data controller from the European Commission. Specific ethical clearance for Spain was obtained from the ethics committee of the Blanquerna School of Psychology, Education and Sport Science (ref. nº 2425016P). While the primary focus was on assessing the nutritional content of food parcels, brief structured interviews were also conducted with organizational staff or volunteers to gather contextual information about the food aid centers. These interviews did not involve the collection of personal or sensitive data. All participants signed informed consent forms and were informed of the aims and voluntary nature of the study.

Not applicable.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Carrillo-Álvarez, E., Muñoz-Martínez, J., Cussó-Parcerisas, I. et al. Nutritional adequacy of charitable food aid packages to the needs of different household-types: a case study in Spain. BMC Nutr 11, 133 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-025-01122-1

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s40795-025-01122-1