Martin Scorsese's Best Movies: A Look at His Cinematic Legacy

Martin Scorsese has never been one to fit neatly into Hollywood. The Academy never felt like home, and the frustrations of the studio system were not much help, either. Marty is, more so, done with the word “content,” and honestly, we feel the same.

Scorsese now publicly mourns how cinema, an all-in art, is being flattened into a business term, stripped of its soul. Algorithms push what’s already popular, and it does not take a rocket scientist to figure out how this suffocates the unexpected, the outliers, and those not abiding by the method.

Even though many heap praise on platforms like Mubi, this doesn’t change the guilt of ignoring overlooked dramas for yet another dog-behavior reality show. One, meanwhile, frequently runs the risk of watching a mediocre piece of film just packaged as arthouse cinema.

At 82, Scorsese is reflecting on life itself – letting go of expectations, material possessions, and even the idea of chasing after things that don’t matter. “The time you spend is spending time,” he says, realizing now, more than ever, how fleeting it all is. Despite all these questions, however, Scorsese is still searching, still creating, discovering what cinema and life can be. With a career spanning over 50 years, let’s take a look at the legacy and films of one of the finest auteurs of modern cinema.

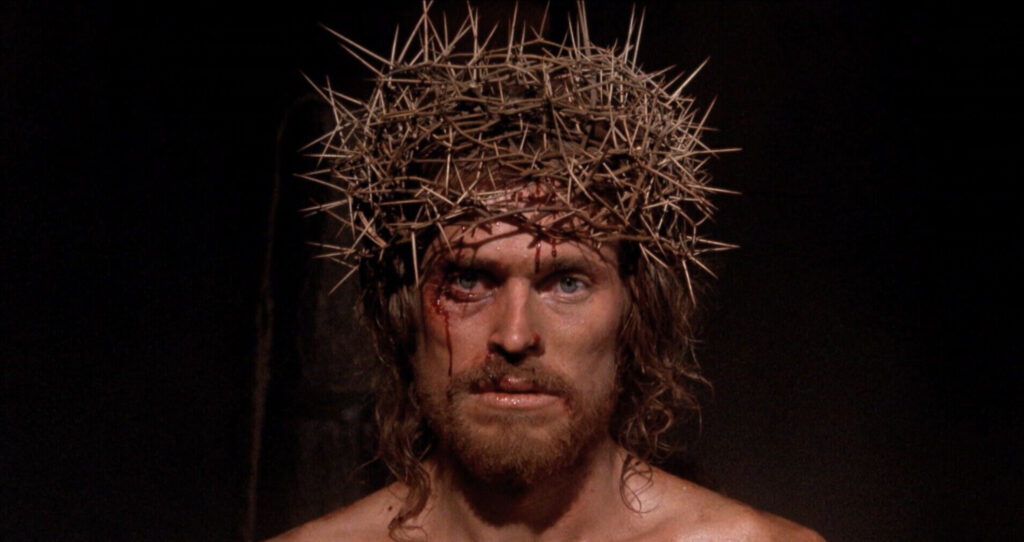

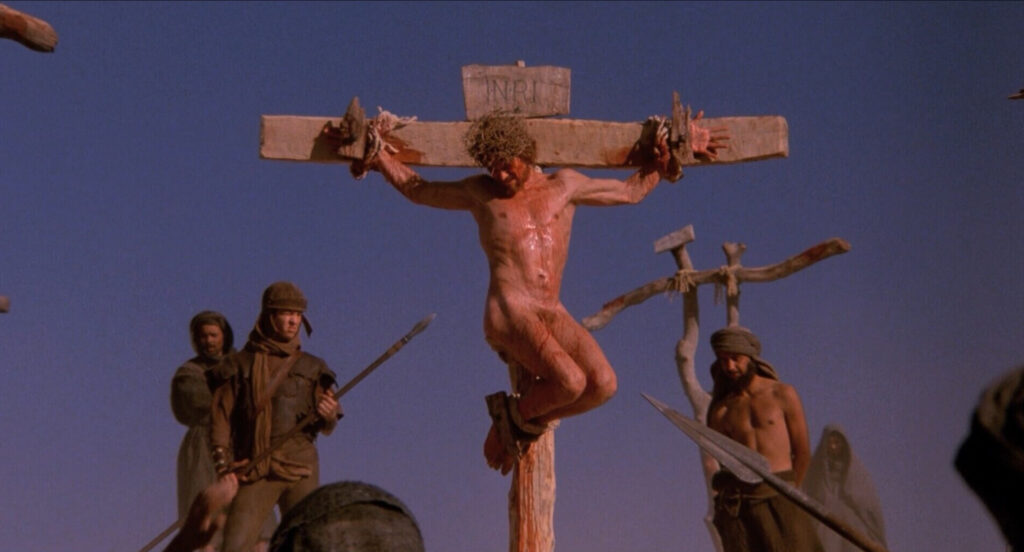

We start our retrospection with Scorsese’s The Last Temptation of Christ, a film that was never going to be received in a vacuum. Released in 1988, it was instantly met with furious protests from religious groups who deemed it blasphemous, even before they had even seen the film. It wasn’t controversial alone; it was dangerous, and Martin Scorsese knew this.

A still from The Last Temptation of Christ | Credits: Universal Pictures

⛶

A still from The Last Temptation of Christ | Credits: Universal Pictures

⛶

A still from The Last Temptation of Christ | Credits: Universal Pictures

⛶

A still from The Last Temptation of Christ | Credits: Universal Pictures

⛶

A still from The Last Temptation of Christ | Credits: Universal Pictures

⛶

In the film, Willem Dafoe’s Jesus is tormented and fallible. He does not stride through the desert as a divine figure removed from human struggle. He doubts, despairs, and even tries to flee from his destiny. This is a Christ who questions whether he is truly the “Son of God” or a man tormented by his existential paradox.

The Last Temptation of Christ is great not because it offers a definitive truth about Jesus but because it lays bare something true about Scorsese himself. He has always wrestled with the weight of his Catholic upbringing – at times obedient, at times in rebellion, at times anguished about whether he was doing enough.

The journey of his Jesus, full of doubt and sacrifice, is the journey of the artist who must create despite the fear that he may not be understood, accepted, or even permitted to continue his work.

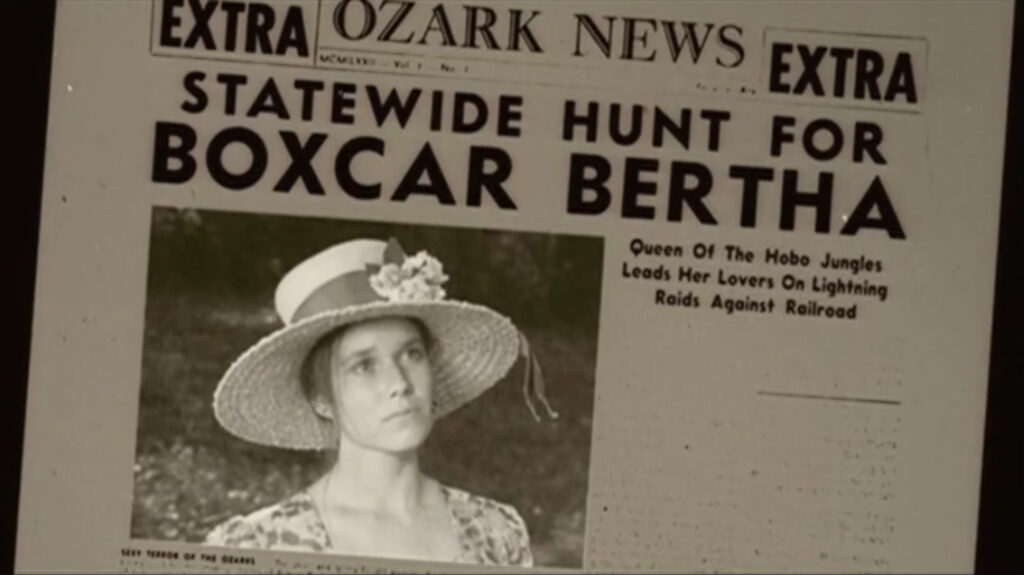

One of Scorsese’s earliest works, Boxcar Bertha tries to sell itself as a steamy exploitation film, but it’s something more than that. Set in the sweaty, dust-choked South during the Depression, it follows Bertha, a young drifter who falls in with a ragtag group of outlaws.

She meets Big Bill Shelley, a union organizer, along with gambler Rake Brown and shotgun-loving Von Morton. One moment of impulsive violence – Bertha shooting a man to protect Rake – forces them into proper criminal territory.

A still from Boxcar Bertha | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

A still from Boxcar Bertha | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

A still from Boxcar Bertha | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

A still from Boxcar Bertha | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

A still from Boxcar Bertha | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

At first look, it’s got a Bonnie and Clyde vibe, but Scorsese isn’t here to make crime look fun. The violence in Boxcar Bertha isn’t stylish or thrilling – it’s blunt, ugly, and inevitable. The gang’s life is a loop of train-hopping, running, and barely scraping by. No matter how far they go, they always seem to end up right back where they started, as if trapped on an endless railroad track to nowhere.

Even within the limits of a low-budget B-movie, Scorsese brings to life a world that feels lived in. The visuals are striking, the mood is thick with desperation, and there are hints of the greatness he’d later achieve. It’s not perfect, but it’s unmistakably a Scorsese film.

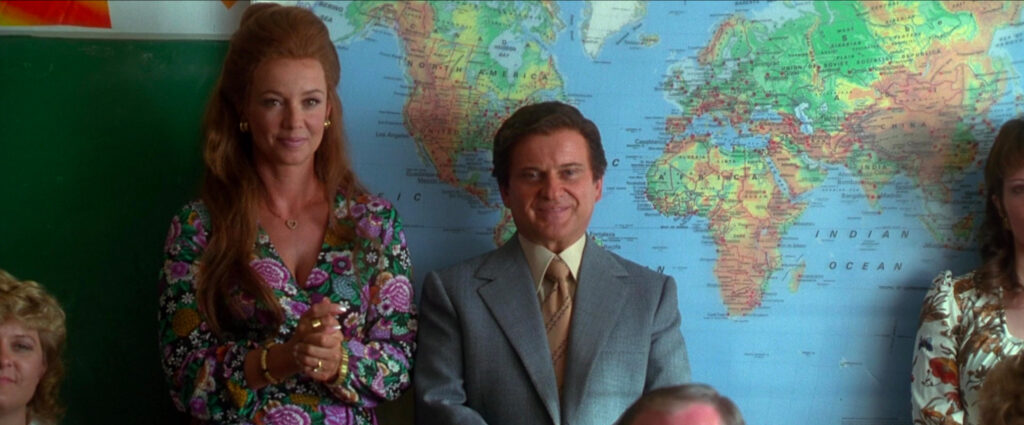

Martin Scorsese’s New York, New York is an oversized love letter to the big band era. It never quite comes together as a full story, but if you let go of expectations, there’s plenty to enjoy.

The film follows two artists trying (and failing) to make a life together. Jimmy is a wildly talented but hot-headed saxophonist, meanwhile, Francine is an up-and-coming singer with the kind of star power that makes you forget about everything else – until it starts overshadowing her husband’s own dreams.

A still from New York, New York | Credits: Chartoff-Winkler

⛶

A still from New York, New York | Credits: Chartoff-Winkler

⛶

A still from New York, New York | Credits: Chartoff-Winkler

⛶

A still from New York, New York | Credits: Chartoff-Winkler

⛶

A still from New York, New York | Credits: Chartoff-Winkler

⛶

He drinks too much, fights too much, and eventually can’t handle that she’s outshining him. Their marriage crumbles in showbiz fashion, culminating in a tearful split in the maternity ward after the birth of their child.

The sets are bright, the big band music energy is infectious, and everything has that warm, nostalgic glow. The title song, “New York, New York,” will be stuck in your head. But the story itself is thin. The characters are mostly surface-level, and De Niro’s performance as the volatile, jealous Jimmy almost feels like he’s playing Travis Bickle at times.

The Color of Money doesn’t quite hit that Scorsese mark. It’s not a bad movie, but it’s just not as exciting as you’d expect from him. It feels like a conventional, studio-driven sequel and continues the story of “Fast Eddie” Felson from The Hustler (1961), but it lacks the director’s usual fire.

A still from The Color of Money | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

A still from The Color of Money | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

A still from The Color of Money | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

A still from The Color of Money | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

A still from The Color of Money | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

Paul Newman reprises his role as Eddie, now a liquor salesman who’s long left the pool halls behind. One night, he spots Vincent (Tom Cruise), a young, cocky pool prodigy with natural talent but zero discipline. Eddie naturally sees dollar signs.

The setup is strong, and there are some great moments, especially in the tension between Vince and his girlfriend. But the film never really digs into the depths of its characters the way Scorsese’s best movies do. Instead, it only raises the bar enough to feel like a by-the-numbers Hollywood sports drama.

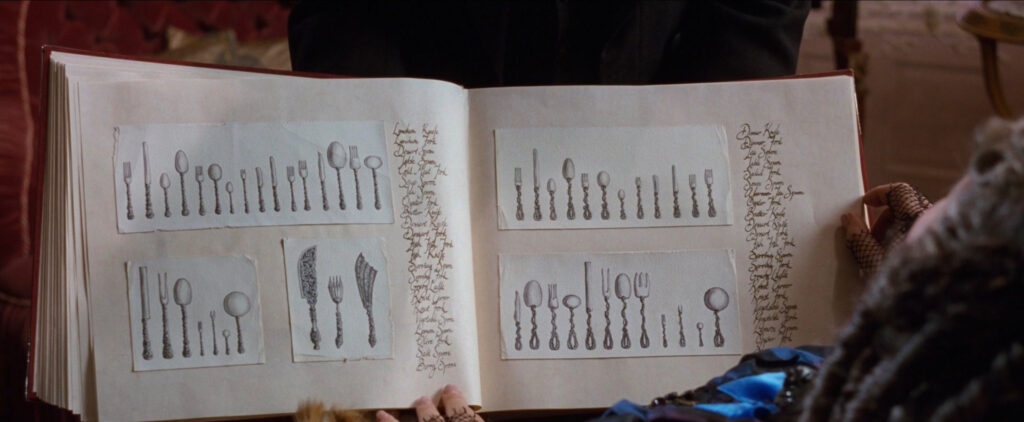

The Age of Innocence might seem like an unexpected film from Martin Scorsese. But deep down, this story isn’t so different. Newland Archer (Daniel Day-Lewis) is engaged to the sweet and proper May Welland (Winona Ryder). But then he meets her cousin, Countess Ellen Olenska, who is everything May isn’t – free-spirited, artistic, and willing to break the rules.

A still from The Age of Innocence | Credits: Columbia

⛶

A still from The Age of Innocence | Credits: Columbia

⛶

A still from The Age of Innocence | Credits: Columbia

⛶

A still from The Age of Innocence | Credits: Columbia

⛶

A still from The Age of Innocence | Credits: Columbia

⛶

Newland falls for her, but in his world, love isn’t a good enough reason to change course. Society decides what’s right, and he follows along. As the narrator, Joanne Woodward, puts it, “The real thing was never said or done or even thought, but only represented by a set of arbitrary signs.”

This world is just as controlling as the mafia stories Scorsese usually tells. In those, stepping out of line means violence. Here, it means silent judgment, exile, and loneliness. Newland thinks he has choices, but by the time he realizes he doesn’t, it’s too late. The Age of Innocence is about the kind of heartbreak that happens in plain sight, in a world where everyone pretends not to notice.

Martin Scorsese’s Who’s That Knocking at My Door? is an impressive debut. Although occasionally obvious, it introduces a filmmaker of great promise. Unlike the exaggerated “swinging youth” of Hollywood, Scorsese’s characters in this film, young Italian-American men in New York, pass time idly, debating where the action is but rarely finding it.

A still from Who’s That Knocking at My Door? | Credits: Trimod Films

⛶

A still from Who’s That Knocking at My Door? | Credits: Trimod Films

⛶

A still from Who’s That Knocking at My Door? | Credits: Trimod Films

⛶

A still from Who’s That Knocking at My Door? | Credits: Trimod Films

⛶

A still from Who’s That Knocking at My Door? | Credits: Trimod Films

⛶

Harvey Keitel plays a young man torn between his rough neighborhood upbringing and a college-educated woman he meets on the Staten Island ferry. Their relationship, subtly acted and naturally filmed, falters when he learns she is not a virgin.

Some scenes misfire, including a r*pe sequence and an awkwardly inserted fantasy scene added for distribution. Scorsese’s gift for capturing honest moments, however, shines, particularly in group dynamics and barroom conversations.

After Hours is supposed to be a comedy by definition; it ends happily and hints that we shouldn’t take it too seriously. Nevertheless, the tension and blended surrealism make it unbearably unsettling. The film follows Paul Hackett, a lonely word processor who meets a charming woman and ventures to SoHo for what he expects to be a romantic night.

A still from After Hours | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from After Hours | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from After Hours | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from After Hours | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from After Hours | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

He’s, however, swept into a Kafkaesque journey of bizarre encounters. SoHo becomes an underworld of strangers, oddball artists, and vindictive mobs. Each character – Teri Garr’s waitress, Linda Fiorentino’s sculptor, and John Heard’s bartender- just makes things more strange.

Like Taxi Driver and Mean Streets, the film explores New York as both a setting and a state of mind. Both hilarious and harrowing, After Hours is an unpredictable fever dream and one of Scorsese’s most original works.

Martin Scorsese’s Kundun is a spiritual film, but it struggles to portray the Dalai Lama as a living, breathing human. Unlike The Last Temptation of Christ, where Jesus battles with his humanity, Kundun presents the 14th Dalai Lama as an icon, a vessel for an eternal spirit.

The film reveals itself in a series of strikingly composed episodes. Despite its devotion to faith and tradition, however, it lacks narrative urgency. The film’s beauty – Roger Deakins’ cinematography and its immersive Buddhist atmosphere – make it feel like an act of reverence rather than drama.

A still from Kundun | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

A still from Kundun | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

A still from Kundun | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

A still from Kundun | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

A still from Kundun | Credits: Buena Vista

⛶

Scorsese, ever drawn to the spiritual, seeks transcendence here but remains at a distance from his subject. Kundun is admirable, even mesmerizing, yet oddly remote – an exquisite tribute, but not one many long to revisit.

Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore opens with a parody of old Hollywood dreams – a little girl against a technicolor sunset, determined to do things her way. But by 35, Alice Hyatt has settled into a routine: a distant husband, a sharp son, and idle chatters with neighbors.

When her husband dies in an accident, she’s left not just widowed but independent – an unexpected prospect. Determined to chase her childhood dream of singing, Alice sells everything and goes on a journey through the Southwest. Reality, however, is messier than fantasy.

A still from Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Alice Doesn’t Live Here Anymore | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

Along the way, she encounters kind strangers, predatory men (notably Harvey Keitel’s Ben), and the grind of waitressing. Ellen Burstyn’s Oscar-winning performance makes Alice vibrant – funny, flawed, and resilient. With mythic undertones, this is Scorsese’s perceptive portrait of a woman figuring out life on her own terms.

Martin Scorsese’s Bringing Out the Dead follows Frank (Nicolas Cage), a paramedic drowning in misery. “I was a grief mop,” he says, more witness than savior. He works three nights in Hell’s Kitchen, haunted by the dead and accompanied by three partners – Larry, who numbs himself with food; Marcus, a gospel showman; and Walls, teetering on madness.

A still from Bringing Out the Dead | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Bringing Out the Dead | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Bringing Out the Dead | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Bringing Out the Dead | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Bringing Out the Dead | Credits: Paramount

⛶

It’s a hypnotic descent into inferno, from a high-rise drug den to the ER of “Perpetual Misery.” Cage delivers his finest work since Leaving Las Vegas, playing a man whose job never ends. Tell us about that, huh? Unlike Fight Club, which glamorizes pain, Bringing Out the Dead sees violence for what it is – unromantic and inescapable.

Robert De Niro excels at playing closed-off, unknowable men – hardened by life, mysteries to themselves. At 75, he played another such role in Martin Scorsese’s The Irishman, a film on crime, politics, and time’s march.

Adapted by Steve Zaillian from I Heard You Paint Houses, the three-and-a-half-hour film chronicles Frank Sheeran, a WWII vet turned hitman and union leader, in a world of power and violence alongside Jimmy Hoffa (Al Pacino) and Russell Bufalino (Joe Pesci). This is one of those ‘the boys are back’ films.

A still from The Irishman | Credits: Netflix

⛶

A still from The Irishman | Credits: Netflix

⛶

A still from The Irishman | Credits: Netflix

⛶

A still from The Irishman | Credits: Netflix

⛶

A still from The Irishman | Credits: Netflix

⛶

Scorsese’s direction is contemplative here. De-aging effects falter, but performances go beyond, with De Niro’s presence anchoring the film’s weighty themes – loyalty, denial, and the moral fog of history.

Frank sees his life as something that happened to him rather than the choices he made. As the film’s final image comes on, Scorsese offers no easy answers. Like Frank, like God, The Irishman remains tight-lipped, demanding we complete it ourselves.

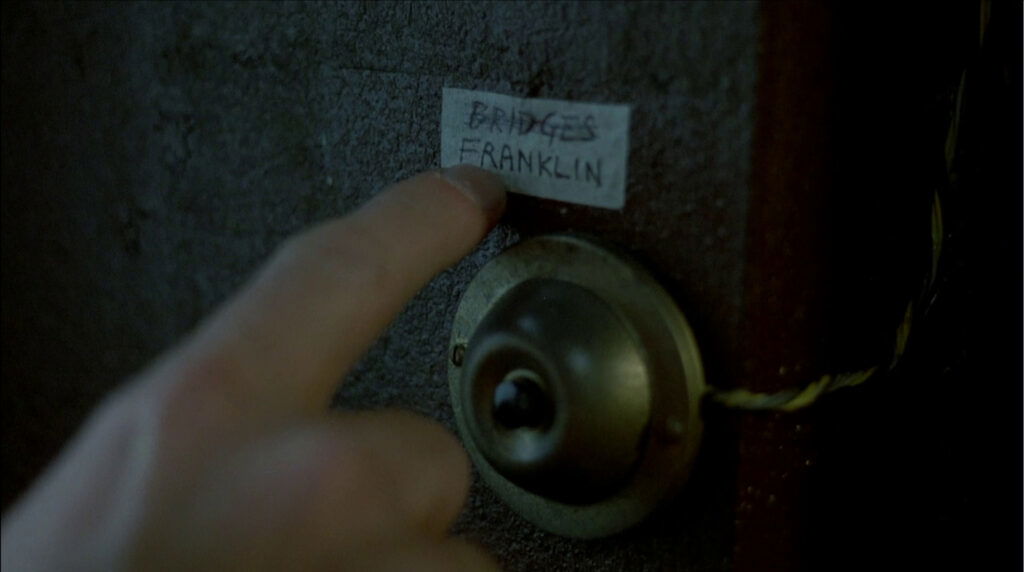

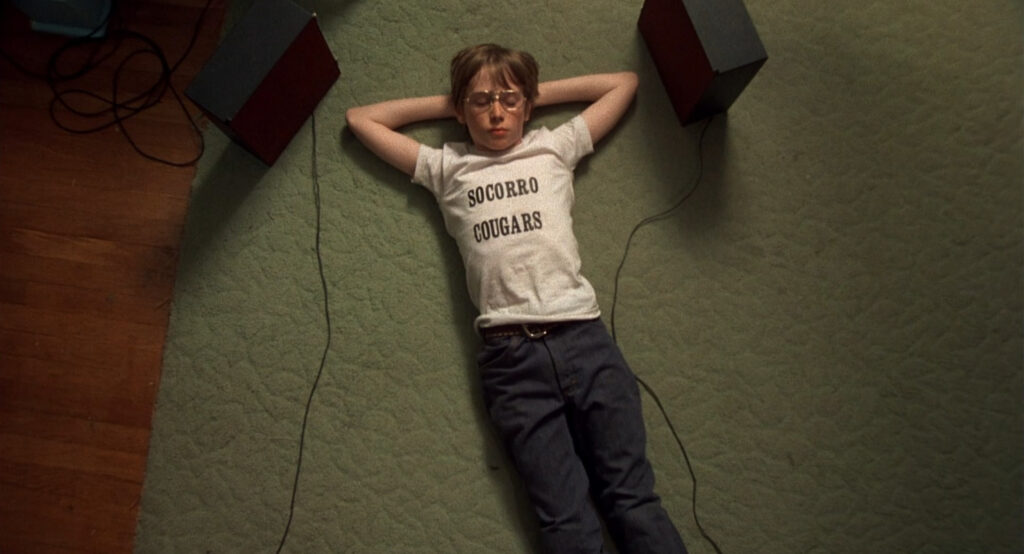

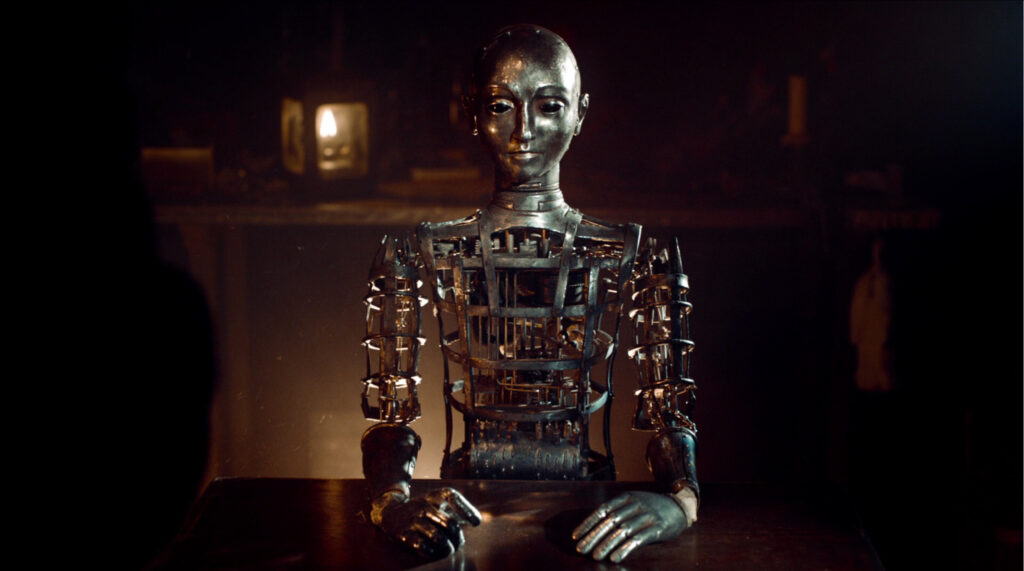

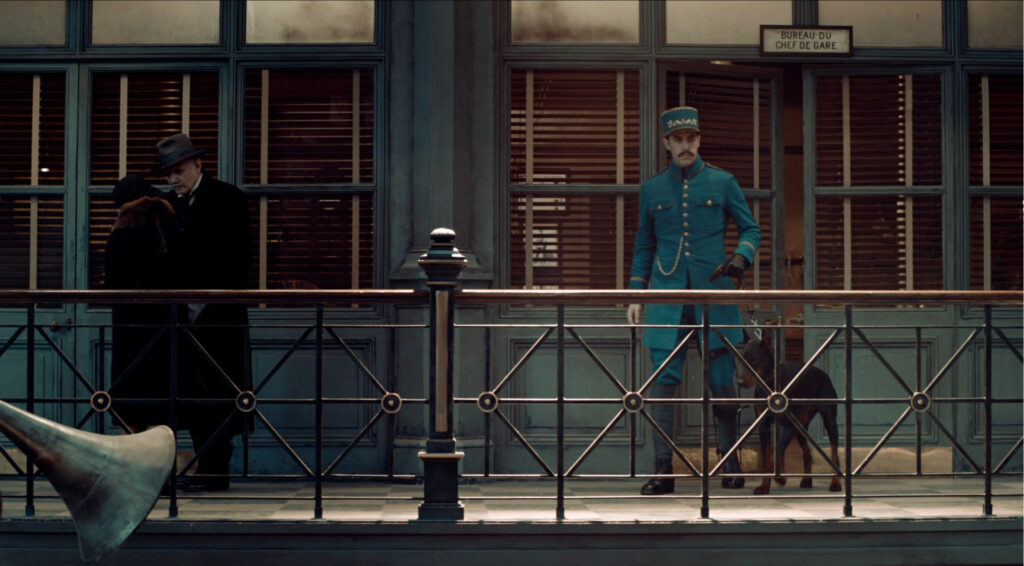

Hugo is unlike any other Scorsese film – yet it feels one of his most personal. A lavish 3D family epic, it’s a love letter to cinema. Set in 1930s Paris, it follows Hugo Cabret, a boy who secretly maintains the clocks in a bustling train station while pursuing his late father’s dream of restoring a broken automaton.

His path crosses with Georges Méliès, a grumpy toy shop owner – once the pioneering filmmaker behind A Trip to the Moon (1902). Scorsese parallels his own childhood – an asthmatic boy absorbing cinema from afar – with Hugo’s journey of discovery.

A still from Hugo | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Hugo | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Hugo | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Hugo | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Hugo | Credits: Paramount

⛶

The film’s first half is filled with chases and a lovely Parisian backdrop; the second celebrates early cinema, from Méliès’ magical films to the tragedy of lost reels. Unlike gimmicky 3D, however, Scorsese uses it well, evoking early wonders like the Lumière brothers’ Arrival of a Train (1896). Ultimately, Hugo champions film preservation – a true happy ending.

Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy is one of the most arid, painful films I have ever seen – so restrained it feels ready to explode, yet never does. Unlike Taxi Driver or Mean Streets, this is a film of bottled-up emotions, rejection, and isolation, without the release of comedy or tragedy.

A still from The King of Comedy | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

A still from The King of Comedy | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

A still from The King of Comedy | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

A still from The King of Comedy | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

A still from The King of Comedy | Credits: 20th Century Fox

⛶

The first time one sees it, it’s hard to like, but even harder to shake it off. A second viewing, without expectations, allows one to appreciate its brilliance. Robert De Niro’s Rupert Pupkin is a delusional aspiring comedian, persistently pursuing a late-night talk show host (Jerry Lewis). His obsession leads to repeated rejections, an intrusion into Jerry’s home, and finally, a kidnapping.

Scorsese directs without payoffs – no reaction shots, no catharsis. It’s frustrating yet effective, an emotional desert in his otherwise vibrant filmography. The King of Comedy isn’t fun, but it lingers, unsettling and unsatisfying in a way only great films can be.

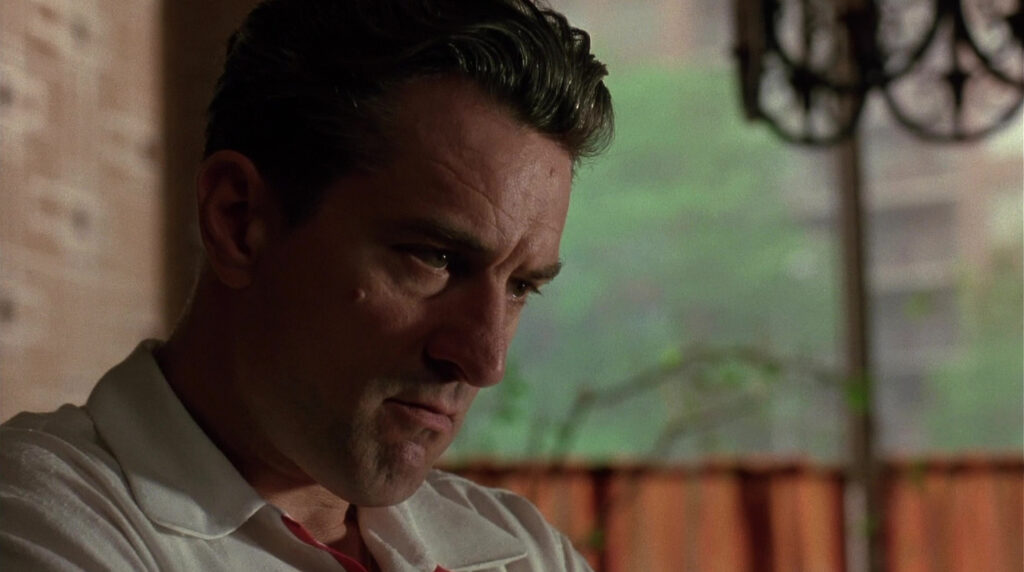

Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon exposes evil in plain sight, following the Osage Nation’s tragic true story. After discovering oil in Oklahoma, the Osage became the wealthiest people per capita – until white men, led by William King Hale (Robert De Niro), began planning their murders for profit. His nephew Ernest (Leonardo DiCaprio) marries Mollie (Lily Gladstone), whose family is targeted one by one.

A still from Killers of the Flower Moon | Credits: Apple Studios

⛶

A still from Killers of the Flower Moon | Credits: Apple Studios

⛶

A still from Killers of the Flower Moon | Credits: Apple Studios

⛶

A still from Killers of the Flower Moon | Credits: Apple Studios

⛶

A still from Killers of the Flower Moon | Credits: Apple Studios

⛶

His longtime muses, De Niro and DiCaprio, deliver great performances, but Gladstone is the revelation here, grounding the film in humanity. While rooted in history, the film resonates even today, revealing how violence and greed have shaped America. By shifting the FBI’s origin story to a personal tragedy, Martin Scorsese shapes an intimate albeit vast narrative – one that forces us to confront the wolves among us. What do we do once we see them?

From its first notes, like wine kept outside for too long, Shutter Island feels uneasy and harsh on the mouth. This is Martin Scorsese’s haunted fortress of dread – a Civil War-era prison for the criminally insane perched on a craggy island off Boston.

U.S. Marshal Teddy Daniels and his partner Chuck (Mark Ruffalo) arrive to investigate a missing prisoner, but the island feels inescapable. Dr. Cawley (Ben Kingsley) welcomes them with charm, yet something is off. The prison’s walls, thick enough to resist cannon fire, hold more than just patients.

A still from Shutter Island | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Shutter Island | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Shutter Island | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Shutter Island | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from Shutter Island | Credits: Paramount

⛶

Flashbacks to World War II tangle Teddy’s mind. Is he the hero of this noir tale or just another man burdened by trauma? Scorsese’s command of atmosphere – stormy nights, crashing waves, whispers – makes reality slip. The ending unsettles, questioning the truth itself. What if we can’t trust what came before? What if the narrator is unreliable? Teddy asks. So do we.

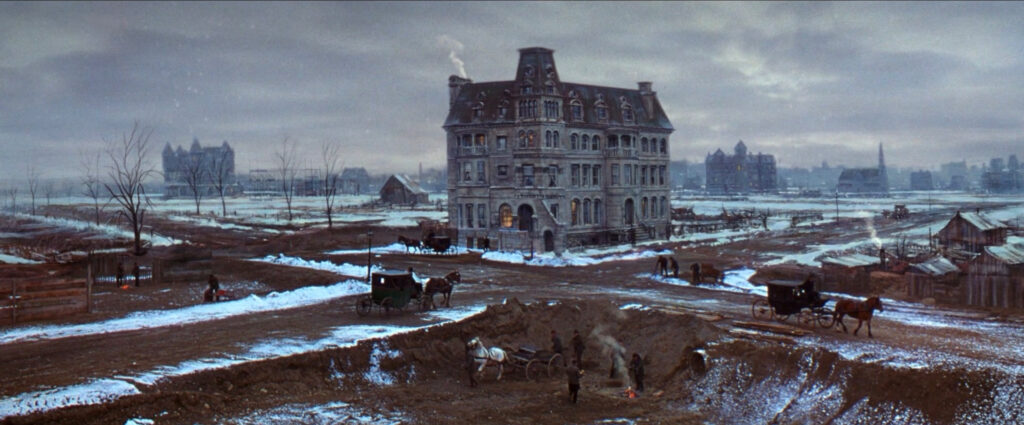

Martin Scorsese’s Gangs of New York tears apart the sanitized myths of American history, reconstructing them into a vision of a nation born in blood. Set in mid-19th-century Manhattan, the film plunges into the lawless Five Points, where rival gangs carve out dominance using just one thing – violence.

A still from Gangs of New York | Credits: Miramax

⛶

A still from Gangs of New York | Credits: Miramax

⛶

A still from Gangs of New York | Credits: Miramax

⛶

A still from Gangs of New York | Credits: Miramax

⛶

A still from Gangs of New York | Credits: Miramax

⛶

The opening sets the stage. Priest Vallon (Liam Neeson) leads his Irish Dead Rabbits into battle against Bill the Butcher’s (Daniel Day-Lewis) Nativists, a fight waged with knives, cleavers, and savagery.

This is Scorsese’s revisionist take on democracy’s violent birth, but lacks the effortless energy of Goodfellas or Casino. It’s powerful, but weighted – some may say even burdened – by its darkness.

Martin Scorsese’s Silence is more an ordeal than a film. Based on Shûsaku Endô’s 1966 novel, it follows two Jesuit priests (Andrew Garfield and Adam Driver) who journey to 17th-century Japan to find their missing mentor (Liam Neeson), rumored to have apostatized under persecution. Captured and imprisoned, Father Rodrigues (Garfield) is forced to question the meaning of faith, suffering, and God’s silence.

A still from Silence | Credits: AI Films

⛶

A still from Silence | Credits: AI Films

⛶

A still from Silence | Credits: AI Films

⛶

A still from Silence | Credits: AI Films

⛶

A still from Silence | Credits: AI Films

⛶

The soundtrack often replaces music with wind, waves, and the crackle of burning flesh. The film doesn’t glorify missionaries but also considers the Japanese perspective, with inquisitor Inoue Masashige calling out Christianity as an invasive force.

Silence resists easy conclusions, posing questions rather than delivering enlightenment. Like much of Scorsese’s work, it wrestles with sin, sacrifice, and grace – perhaps the lifelong inquiry of a lapsed Catholic who never fully abandoned his faith.

Howard Hughes, once the world’s richest man, ended his life in isolation, sealing himself away in a Vegas penthouse and later a Beverly Hills bungalow. The Aviator follows his journey from a daring young tycoon to a man consumed by obsession.

A still from The Aviator | Credits: Miramax

⛶

A still from The Aviator | Credits: Miramax

⛶

A still from The Aviator | Credits: Miramax

⛶

A still from The Aviator | Credits: Miramax

⛶

A still from The Aviator | Credits: Miramax

⛶

Scorsese captures both his triumphs – Hollywood success, aviation breakthroughs, and romances with icons like Katharine Hepburn – and his descent into madness. With breathtaking visuals also on the platter and a gripping arc, The Aviator is a deeply human portrait of genius, excess, and inevitable decline – it is one of Scorsese’s finest works.

Martin Scorsese’s Cape Fear reimagines the 1962 original through a more complex and dirtier lens. Sam Bowden is no longer a noble hero but a flawed and damaged defense attorney haunted by his past. His family – his wife and rebellious daughter – already falling apart before Max Cady (Robert De Niro) even resurfaces after his incarceration.

A still from Cape Fear | Credits: Cappa Films

⛶

A still from Cape Fear | Credits: Cappa Films

⛶

A still from Cape Fear | Credits: Cappa Films

⛶

A still from Cape Fear | Credits: Cappa Films

⛶

A still from Cape Fear | Credits: Cappa Films

⛶

Cady, who is covered in biblical tattoos, lurks just within the law, tormenting Bowden at every turn he gets the chance. But Scorsese’s eventual reveal is that no one is truly innocent. While executed rather well, Cape Fear feels more like a genre exercise than a personal work – an impressive film, but not an evolution for the director.

The film that put him on the map, Mean Streets, is all about the small-time guys -young enforcers, gamblers, and hustlers just trying to get by in Little Italy. Charlie (Harvey Keitel) is one of them. He’s a rising mob enforcer with a decent suit, big dreams, and a lot of guilt.

A still from Mean Streets | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Mean Streets | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Mean Streets | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Mean Streets | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Mean Streets | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

His uncle, the much-feared Giovanni, is helping him move up, even offering him a restaurant taken from someone who couldn’t pay their debt. But Charlie’s got problems. He’s torn between his Catholic beliefs, his ambitions, and his loyalty to his best friend, Johnny Boy (Robert De Niro), who is a walking disaster.

The movie is packed with bar fights, street brawls, and shocking violence that comes out of nowhere. The soundtrack, full of classic rock and pop, makes every scene feel even more alive. Don’t ask me why; no one knows. That’s just Mean Streets.

Las Vegas, like the Mafia, fulfills a universal need – a belief in places and people who play outside the rules. Martin Scorsese’s Casino looks at the mob’s grip on Vegas through Sam “Ace” Rothstein, a numbers genius who runs casinos with a ruthless efficiency. But trouble arrives in two forms. The violent Nicky Santoro and the seductive Ginger McKenna.

A still from Casino | Credits: Universal

⛶

A still from Casino | Credits: Universal

⛶

A still from Casino | Credits: Universal

⛶

A still from Casino | Credits: Universal

⛶

A still from Casino | Credits: Universal

⛶

Scorsese lays bare the operations – how they skim millions and ultimately lose it all when corporate interests take over. Once, under guys like Ace and Nicky, gamblers believed they had a shot. But today, the machine is too perfect. Vegas isn’t run by criminals anymore, it’s run by corporations. And the house always wins.

Martin Scorsese’s The Wolf of Wall Street is shameless. It is, perhaps, one of the most entertaining films ever made about despicable men. Leonardo DiCaprio’s Jordan Belfort, a Queens-born stockbroker-turned-con artist, is the living embodiment of Wall Street’s worst excesses.

A still from The Wolf of Wall Street | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from The Wolf of Wall Street | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from The Wolf of Wall Street | Credits: Paramount

⛶

A still from The Wolf of Wall Street | Credits: Paramount

⛶

Scorsese drowns us in their world – parties, financial scams, and Quaaludes. The disgust is clear: these men exploit, cheat, and laugh at the consequences. And still, America enables them, addicted to wealth and power. We laugh at The Wolf of Wall Street, but the real wolves, past and present, are laughing at us.

Despite being nominated for five Oscars, The Wolf of Wall Street walked away empty-handed, but it remains one of Scorsese’s most audacious and entertaining films.

Unlike his past films about men striving to realize their self-image, Martin Scorsese’s The Departed follows two men trapped in lives that contradict who they truly are. Inspired by Infernal Affairs (2002), it changes a Hong Kong thriller into an American – and Catholic – meditation on sin.

A still from The Departed | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from The Departed | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from The Departed | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from The Departed | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from The Departed | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

Set in Boston, the film follows Colin (Matt Damon), a gangster hiding in the police, and Billy (Leonardo DiCaprio), a cop undercover in the mob. Each becomes entangled in their deception, questioning their loyalties. With Nicholson’s calculating mob boss and Farmiga’s conflicted psychologist, The Departed becomes an examination of conscience, where confession may come too late.

After years of being snubbed by the Academy, Scorsese finally won his first (and only) Best Director Oscar for The Departed, and while many argue that it should have come before, at least it finally did.

Some films leave an imprint that never fades – so much so that it becomes a trope, and GoodFellas is definitely one of them. It does not take a film buff to know that. First released in 1990, Martin Scorsese’s gangster story captures the rise and fall of Henry Hill in the mafia, taking audiences into a world that feels glamorous yet hollow.

A still from Goodfellas | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Goodfellas | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Goodfellas | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Goodfellas | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

A still from Goodfellas | Credits: Warner Bros.

⛶

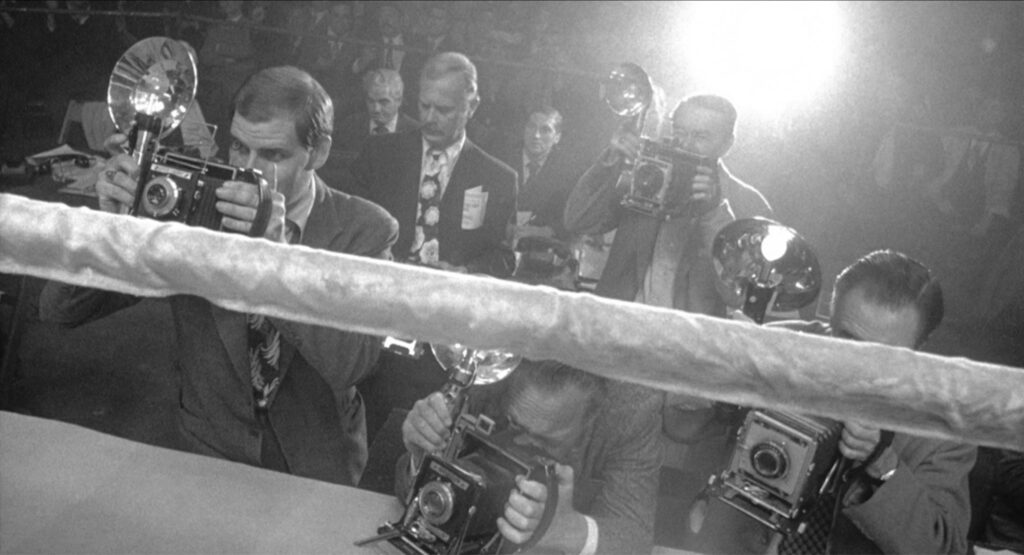

If Coppola’s The Godfather is the Shakespearean tragedy of the mafia world, Goodfellas is its blabbering and cocaine-addicted cousin. Scorsese’s camera work here, especially the legendary Copacabana tracking shot, is quite frankly, amazing, and the soundtrack, packed with hits from the ‘50s to the ‘70s, turns every scene into a funky experience.

Goodfellas didn’t win Best Picture (losing to Dances with Wolves), but its influence is undeniable. Since then, every gangster movie has tried to capture its magic, but none has fully matched it. (Well, apart from that one Community episode).

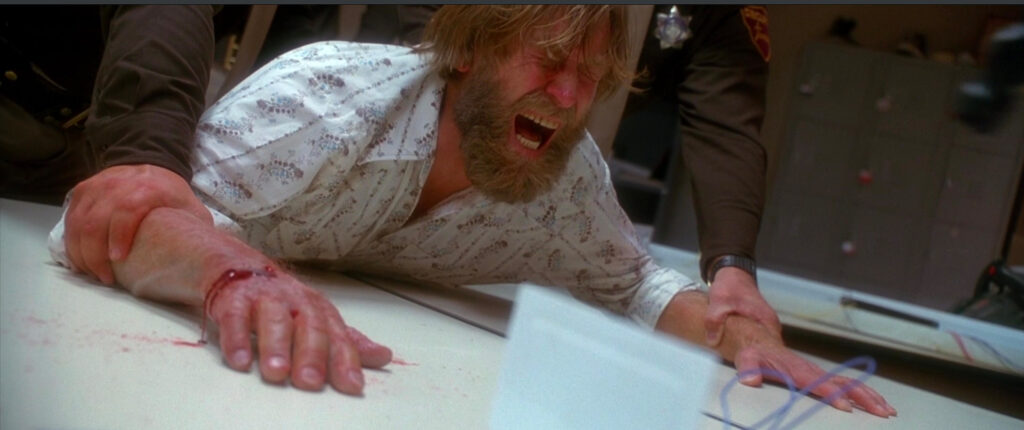

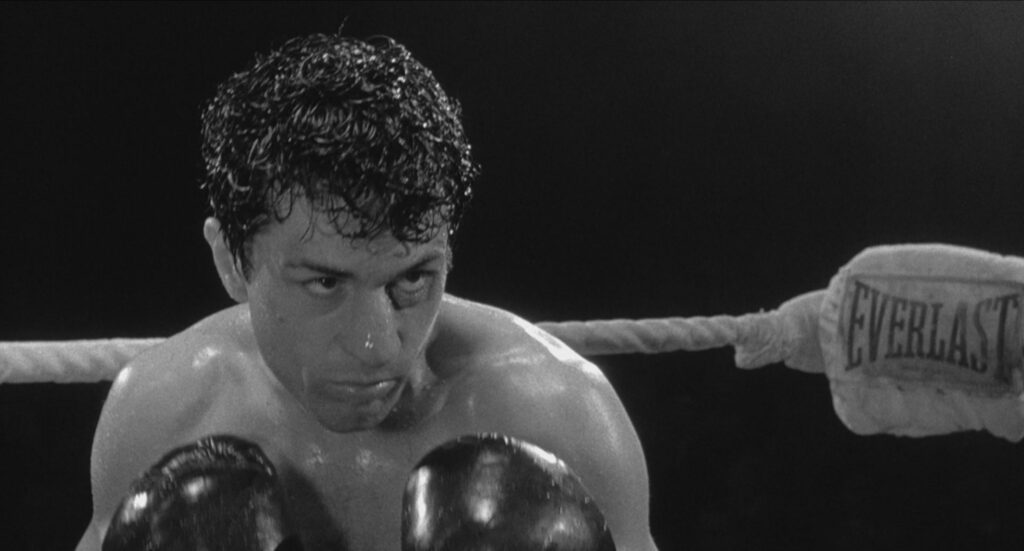

It is easy to reduce Raging Bull to just another boxing film. It is, however, about Jake LaMotta’s paralyzing jealousy and sexual insecurity. The ring becomes his confessional, where punishment serves as penance. Strategy is irrelevant, his fights are driven by fear and rage. When his wife, Vickie, offhandedly calls an opponent “good-looking,” he brutalizes the man to seek validation and reverence in her eyes.

A still from Raging Bull | Credits: United Artists

⛶

A still from Raging Bull | Credits: United Artists

⛶

A still from Raging Bull | Credits: United Artists

⛶

A still from Raging Bull | Credits: United Artists

⛶

A still from Raging Bull | Credits: United Artists

⛶

Raging Bull was almost never made. De Niro, however, pushed for it, seeing LaMotta’s story as a vehicle for Scorsese’s redemption. It won Oscars for De Niro and editor Thelma Schoonmaker, though Ordinary People took Best Picture.

Shot in black and white, its fight scenes use slow motion, animalistic soundscapes, and a distorted ring to reflect Jake’s inner psyche. Many may see it as Othello for modern times – a cutting study of masculinity, self-loathing, and obsession, where LaMotta’s greatest opponent is himself.

When it is not being used by dude-bros to justify certain questionable behaviours (much like Fight Club), Martin Scorsese’s Taxi Driver is about a lonely Vietnam vet driving a cab through the city’s darkest corners.

Travis Bickle is disgusted by the filth around him but keeps coming back to it, almost feeding on his anger. He watches from the outside as other men, corrupt politicians, street pimps, seem to move through life effortlessly and rather nonchalantly, while he’s stuck, unwanted, somehow always getting it wrong.

A still from Taxi Driver | Credits: Columbia

⛶

A still from Taxi Driver | Credits: Columbia

⛶

A still from Taxi Driver | Credits: Columbia

⛶

A still from Taxi Driver | Credits: Columbia

⛶

A still from Taxi Driver | Credits: Columbia

⛶

Bickle’s shot at romance burns to a crisp when he cluelessly takes a woman to a porno theater. Later, as she rejects him over the phone, the camera drifts away, like even the movie can’t bear to watch. But when Travis snaps and goes on a killing spree, we see everything in painful slow motion. Robert De Niro simmers with a strange rage, and the film pulls us into his feverish breakdown.

Taxi Driver lays bare the loneliness and alienation in the urban jungle of 1970s New York City. The film’s neon-lit cinematography, Bernard Herrmann’s score, and De Niro’s performance combine to create a compelling and endlessly quotable film. “You talkin’ to me?”

It’s no surprise that Taxi Driver won the Palme d’Or at Cannes and secured four Academy Award nominations. It remains one of the most unsettling and thought-provoking films in his oeuvre and arguably Scorsese’s finest.