AIDS Research and Therapy volume 22, Article number: 68 (2025) Cite this article

Despite advancements in HIV prevention strategies, including pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP), uptake remains suboptimal in high-burden regions like Africa. Healthcare workers (HCWs) play a pivotal role in PrEP implementation. This study systematically reviews the scientific literature to evaluate the knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of healthcare workers in offering pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in Africa.

This systematic review and meta-analysis followed PRISMA guidelines, synthesizing qualitative and quantitative studies from PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Google Scholar (2010–2024). We included studies that assessed HCWs’ PrEP-related knowledge, attitudes, and willingness in African settings. Pooled proportions for key outcomes were calculated using random-effects models, and barriers/facilitators were thematically analyzed.

Of 293 screened records, 34 studies conducted in 12 countries were included. Meta-analysis revealed high PrEP awareness (85%, 95% CI: 75–91%) but poor knowledge (18%, 95% CI: 4–55%). Attitudes were moderately positive (46%, 95% CI: 25–68%), and willingness to prescribe PrEP was 58% (95% CI: 43–72%). Key barriers included stigma, inadequate training, workload, concerns about risk compensation, and health system constraints. Facilitators included provider training, experience, and integrated service delivery.

While PrEP awareness is high among African HCWs, knowledge gaps and attitudinal barriers hinder optimal implementation. Targeted interventions—such as structured training, stigma reduction, and health system strengthening—are critical to enhancing PrEP adoption. Future research should explore context-specific strategies to improve HCW engagement in PrEP programs.

The Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (HIV/AIDS) remains a significant global health challenge, with over 40 million people currently living with the virus. The burden is greatest in low- and middle-income countries, particularly in Asia and Sub-Saharan Africa [1]. In 2023 alone, more than 1.3 million new infections were recorded, despite ongoing advancements in prevention and treatment [1].

Persistent challenges—such as stigma, delayed healthcare-seeking, poor adherence to antiretroviral therapy (ART), and inadequate healthcare infrastructure—continue to drive new infections in high-burden settings [2]. In response, global health initiatives have developed various comprehensive strategies, including educational campaigns promoting safer sexual practices, the widespread use of ART to achieve viral suppression, increased access to rapid diagnostic tests, and the introduction of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) [2, 3].

PrEP has emerged as a key biomedical prevention strategy, involving the use of antiretroviral medications by HIV-negative individuals—particularly high-risk groups such as men who have sex with men (MSM) and female sex workers—to prevent infection [4]. Following approval by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2012 and endorsement by the World Health Organization (WHO) endorsed PrEP in 2015, multiple studies have demonstrated the efficacy of PrEP in reducing HIV incidence. A meta-analysis reported an estimated 51% reduction in HIV infection risk among individuals using PrEP consistently [4, 5].

Newer formulations, such as long-acting injectable cabotegravir, has further enhanced PrEP’s effectiveness and adherence [6]. Despite these advancements, uptake remains disproportionately low in high-burden regions [6]. This is due to factors such as limited awareness, high costs, concerns over long-term side effects, stigma, healthcare providers’ lack of knowledge regarding PrEP guidelines, and potential drug resistance [6, 7].

Healthcare providers play a crucial role in promoting PrEP use among individuals at elevated risk of HIV infection [7]. Their knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to offer PrEP significantly influence its recommendation and uptake. While individual studies have explored these provider-related factors in Africa, few comprehensive syntheses currently exist. Therefore, this study aims to assess healthcare professionals’ knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to use PrEP in Africa, as well as to identify barriers limiting its widespread implementation in the region.

This was a systematic review and meta-analysis of studies evaluating the knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of healthcare workers to offer pre-exposure prophylaxis in African countries. This review is reported following the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PRISMA) criteria [8]. This systematic review was registered with the International Prospective Register of Systematic Reviews and Meta-analyses (PROSPERO ID: CRD420250651473).

Because this review was descriptive, we used the PICo framework to define our inclusion criteria [9]. We included studies that evaluated healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, and willingness to offer pre-exposure prophylaxis to high-risk populations in Africa. Healthcare workers could be physicians, clinical officers, nurses, counselors, pharmacists, community health workers, or other health professionals. Study settings could be community, primary, secondary, or tertiary health centres in any African country. Both rural and urban contexts were included. Qualitative and quantitative studies were included. Studies had to be published in English Language, and published between 1st January 2010 and 23rd December 2024.

Publications reporting on outcomes from studies conducted outside of Africa, or outside of the target population were excluded. Interventional studies such as quasi-experimental studies and randomized controlled trials were also excluded. Studies not published in the English Language or with unavailable full texts were excluded. Reviews, commentaries, editorials, book chapters, protocols, and conference abstracts were excluded.

A systematic literature search was conducted in December 2024 on PubMed, Cochrane CENTRAL, and Google Scholar. Search terms were related to knowledge, attitudes, perceptions, willingness, healthcare professionals, and Africa. A detailed search strategy employing Boolean operators (such as OR, AND). MeSH terms (on PubMed), truncation, and detailed keywords and synonyms was employed on each database to obtain relevant studies. The detailed search strategy is provided in the additional file. (Additional File 1). We also hand-searched systematic reviews and meta-analyses obtained from our preliminary search to find additional relevant studies.

The primary outcome was to evaluate the knowledge, perceptions, and willingness of healthcare workers to offer pre-exposure prophylaxis to high-risk individuals in Africa. Secondary outcomes included exploring the barriers and facilitators affecting healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to offer pre-exposure prophylaxis in Africa.

A rigorous study selection process was conducted. Firstly, entries were imported into Rayyan and duplicates were removed. Title and abstract screening were done by two independent reviewers using the eligibility criteria. Conflicts were resolved by discussion or by a third reviewer. After the title and abstract screening, four authors conducted the full text screening. Any conflicts that arose from this phase were resolved by discussion or a third reviewer.

Four reviewers independently extracted data from the included studies. Study characteristics such as author, year of publication, country, study design, setting, sample size, mean age, gender distribution, and distribution of healthcare workers were extracted into a standardized table. Data on key outcomes such as knowledge of PrEP, awareness of PrEP, attitudes toward PrEP, and willingness to offer PrEP were extracted. Secondary data such as barriers to offering PrEP, facilitators, and study limitations were also extracted.

The extracted data was synthesized quantitatively and qualitatively.

A meta-analysis was conducted to synthesize quantitative data on the overall proportion of healthcare workers with good knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to offer PrEP to patients in Africa. Outcomes were summarized using pooled proportions with 95% confidence intervals. The random effects model was used for the meta-analyses. Publication bias was assessed using funnel plots. We further assessed statistical heterogeneity with I2, which calculates the variation across studies. Because the number of studies with quantitative data were small, we did not conduct further sub-group analyses. We also used the Chi-square test to calculate heterogeneity, considering p-values less than 0.05 as statistically significant. The meta-analysis was conducted using R version 4.4.2.

For the narrative synthesis, we described the overall outcomes, barriers, and facilitators to healthcare workers’ knowledge, attitude, or willingness to prescribe PrEP. In addition, these barriers and facilitators have been presented in a table.

To assess the methodological quality of the included studies, we used the Joanna Briggs Institute critical appraisal checklists. Four reviewers independently assessed the methodological quality of each study. We used the JBI critical appraisal checklist for qualitative studies to assess the methodological quality of qualitative studies, and we used the JBI critical appraisal checklist for analytic cross-sectional studies to assess the methodological quality of quantitative studies. Any disagreement between the reviewers were settled through discussion or by a third reviewer.

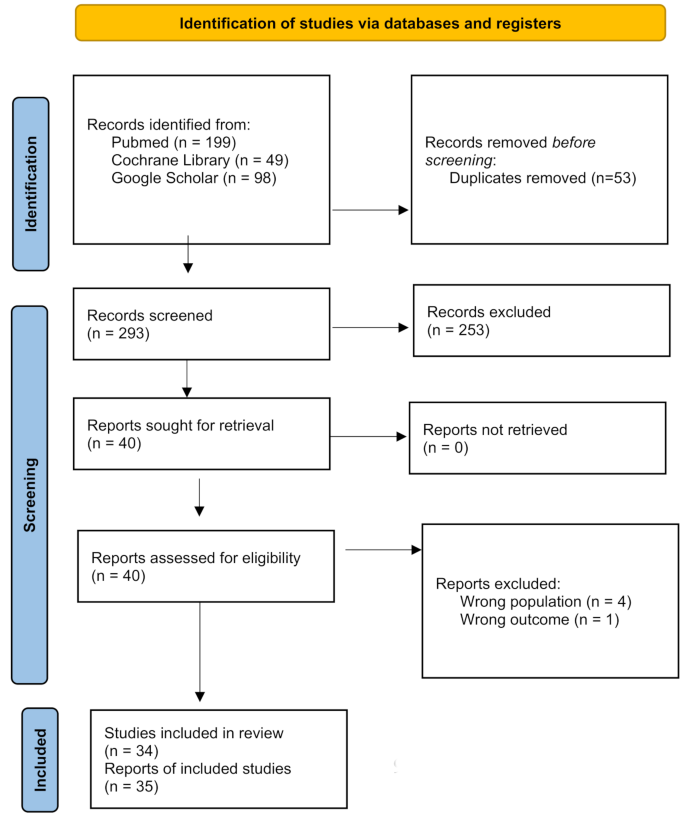

From 293 unique records, we included 35 publications reporting 34 studies in this review. The full PRISMA flow diagram for this study is provided in Fig. 1. Of the studies included in this review, there were 7 quantitative studies [10,11,12,13,14,15,16], 1 mixed methods study [17], and 26 qualitative studies [18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42,43,44]. All cross-sectional studies used questionnaires to collect data. The studies were conducted across 12 countries. Of the single-country studies, 8 studies were conducted in Kenya [18, 21, 23, 28, 29, 31, 36, 42], 8 in South Africa [13, 14, 25, 30, 35, 37, 39, 44], 1 in Tanzania [17], 1 in Rwanda [22], 2 in Congo DRC [10, 40], 1 in Nigeria [11], 2 in Eswatini [12, 24], 1 in Namibia [41], 1 in Lesotho [33], 1 in Zimbabwe [38], 1 in Ghana [43], and 2 in Ethiopia [15, 16]. There were 4 multi-country studies, including Wheelock et al. (Kenya, Uganda, Botswana, South Africa), Lanham et al. (Kenya, South Africa, Zimbabwe), O’Malley et al. (Kenya and South Africa), and Camlin et al. (Kenya, Uganda, Botswana, South Africa) [19, 20, 26, 34]. Most publications were from 2021 upward (n = 25, 71.4%). The total sample size across all studies was 2758. 22 studies reported on gender distribution, with a total of 1362 females out of 2255 participants (60.4% female). 23 studies with a total sample size of 2424 participants reported on the distribution of healthcare workers, with 1216 nurses (50.2%), 481 doctors and clinicians (19.84%), 197 counselors (8.13%), 195 community health workers (8.04%), 95 pharmacists (3.92%), and 240 other professionals (9.90%). Table 1 (Table 1) summarizes the study characteristics.

The JBI critical appraisal checklists were used to evaluate the methodological quality of the included studies. Each question could be answered ‘Yes’, ‘No’, ‘Maybe’, or ‘Unclear’. The results of the study quality assessment are shown in Table 2 (Table 2) and Table 3 (Table 3).

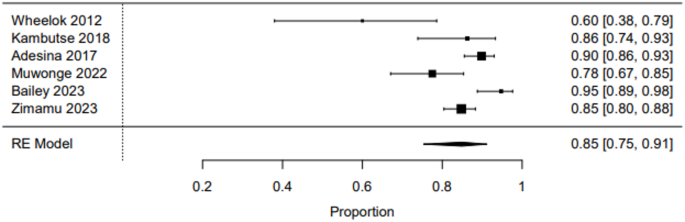

6 studies quantitatively explored the awareness of healthcare workers about PrEP. In Wheelock et al.’s study, awareness was 60%, while Kambutse et al.’s study reported an awareness of 86% [20, 22]. Awareness levels appeared to generally trend upwards and stabilize in further studies. In Adesina et al.’s study, 90% of healthcare workers were aware of PrEP [11]. Muwonge et al.’s study in Uganda revealed an awareness of 78% [32]. Bailey et al.’s study in South Africa revealed the highest awareness levels at 95% [13]. Zimamu’s study revealed an awareness level of 85% [15].

Pooled proportions were calculated to estimate the overall awareness of PrEP among healthcare workers in Africa. 6 studies reported sufficient data to be included in the meta-analysis, which was conducted using the random-effects model [11, 13, 15, 20, 22, 32]. Overall awareness of PrEP among healthcare workers was calculated to be 85% (95% CI 75% − 91%). There was evidence of high heterogeneity (I2 = 86.6%), which was found to be statistically significant (Q = 24.11, p = 0.0002). Figure 2 (Fig. 2) shows the pooled awareness of PrEP among healthcare workers from the meta-analysis.

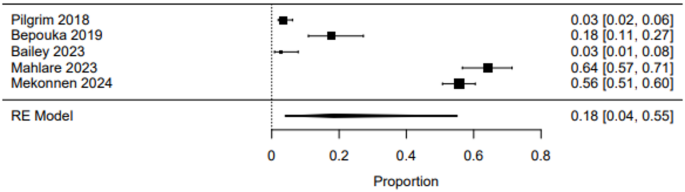

10 studies assessed the knowledge of PrEP among healthcare workers. Pilgrim et al. (2018) evaluated the association between knowledge, attitudes, skills, and willingness to offer PrEP, finding extremely low knowledge of PrEP (3.5%). High levels of skills were associated with willingness to offer PrEP [17]. Bepouka’s study found low levels of good knowledge of PrEP at 17.6% [10]. Kamaara’s qualitative study exploring knowledge of PrEP among healthcare workers and faith leaders found varying results [23]. In Muwonge et al.’s study, training increased knowledge of PrEP [32]. Geldsetzer et al.’s study in Lesotho, however, found high levels of technical and clinical knowledge of PrEP among healthcare workers [33]. Poor knowledge was also seen in Magagula et al.’s study in Eswatini. In Bailey et al.’s study, 3% of respondents had good knowledge; 68% had moderate knowledge [13]. However, in Mahlare et al.’s study, 64.4% of respondents had good knowledge of PrEP [14]. In Zimamu et al.’s study, 43.2% of respondents knew the correct definition of PrEP and 46.6% identified the correct timing of administration. Only 27.3% of respondents knew the contraindications for PrEP [15]. In Mekonnen et al.’s study, 55.7% of respondents had good knowledge of PrEP [16].

Pooled proportions were calculated to estimate the overall proportion of healthcare workers with good knowledge of PrEP in Africa. 5 studies reported sufficient quantitative data and were included in the meta-analysis, conducted using the random-effects model [10, 13, 14, 16, 17]. Overall proportion of healthcare workers with good knowledge of PrEP was calculated to be 18% (95% CI 4% − 55%). There was evidence of high heterogeneity (I2 = 98.8%), which was found to be statistically significant (Q = 199.82, p < 0.0001). Figure 3 (Fig. 3) shows the pooled proportion of healthcare workers with good knowledge of PrEP from the meta-analysis.

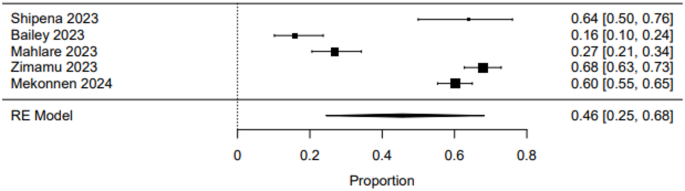

13 studies evaluated the attitudes of healthcare workers towards PrEP. Wheelock et al.’s study revealed that healthcare workers perceived PrEP to have positive benefits in improving HIV prevention and empowering key populations [20]. In Pilgrim et al.’s study, higher scores on the Negative Attitudes Towards Adolescent Sexuality scale was associated with lower levels of willingness to prescribe PrEP [17]. In Kambutse et al.’s study, safe sex promotion and HIV testing and treatment were perceived to be more efficacious than the use of PrEP by more than 60% of healthcare workers [22]. Bärnighausen et al.’s study in Eswatini, however, revealed overall positive attitudes to PrEP [24]. In Lanham et al.’s study, respondents preferred adolescent girls and young women (AGYW) to wait till marriage before initiating sex, although they agreed that AGYW at risk of HIV should be offered PrEP [19]. Geldsetzer’s study in Lesotho revealed positive attitudes towards PrEP [33]. Heterogenous attitudes were found in Camlin’s study, with some healthcare workers’ expressing enthusiasm, while others feared that offering PrEP would lead to increased risk compensation [34]. In Pleaner et al.’s study, participants were largely positively inclined to offering PrEP [39]. Magagula et al.’s study was characterized by moderate attitudes towards PrEP, with a mean score of 46.5 out of 70 points [12]. In Bailey et al.’s study in South Africa, attitudes towards PrEP were largely negative (84.8%) [13]. Similar outcomes were found in Mahlare et al.’s study, with only 26.9% of respondents having positive attitudes [14]. Zimamu et al. and Mekonnen et al.’s studies reported largely positive attitudes, at 68.2% and 60.2% respectively [15, 16].

Pooled proportions were calculated to estimate the overall proportion of healthcare workers with good attitudes towards PrEP in Africa. 5 studies reported sufficient quantitative data to be included in the meta-analysis [13,14,15,16, 41]. The meta-analysis was conducted using the random-effects model. Overall proportion of healthcare workers with good attitudes towards PrEP was calculated to be 46% (95% CI 25% − 68%). There was evidence of high heterogeneity (I2 = 97.74%), which was found to be statistically significant (Q = 126.05, p < 0.0001). Figure 4 (Fig. 4) shows the pooled proportion of healthcare workers with good attitudes to PrEP from the meta-analysis.

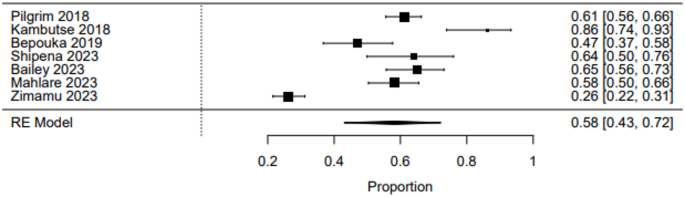

9 studies reported on the willingness of healthcare workers to offer PrEP in Africa. In Pilgrim et al.’s study, 61% of participants demonstrated willingness to offer PrEP [17]. In Kambutse et al.’s study, the willingness value was 86% [22]. In Bepouka et al.’s 2019 study, 47% of healthcare workers were willing to offer PrEP [10]. Shipena’s study found a willingness of 64%, with Bailey’s study finding a similar value of 65% [13, 41]. Mahlare et al.’s study found a moderate willingness at 58% [14]. However, Zimamu et al.’s study reported a relatively low willingness, at 26% [15]. Two qualitative studies did not report quantitative data, however, high levels of willingness were expressed by healthcare professionals [20, 24].

Pooled proportions were calculated to estimate the overall proportion of healthcare workers who were willing to offer PrEP in Africa. Seven studies reported sufficient quantitative data to be included in the meta-analysis [10, 13,14,15, 17, 22, 41]. The meta-analysis was conducted using the random-effects model. Overall proportion of healthcare workers willing to offer PrEP was calculated to be 58% (95% CI 43% − 72%), indicating moderate levels of willingness. There was evidence of high heterogeneity (I2 = 95.28%), which was found to be statistically significant (Q = 120.40, p < 0.0001). Figure 5 (Fig. 5) shows the pooled proportion of healthcare workers willing to offer PrEP from the meta-analysis.

24 studies reported on the barriers to good knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of offer PrEP by healthcare workers.

Barriers included: increased workload [21, 22, 31, 32, 39, 44], poor training [18, 20, 26, 31, 39, 44], poor risk perception [18, 34], stigmatizing attitudes [17, 19,20,21,22, 29, 31,32,33, 35, 37, 39], concerns about poor adherence [12, 19, 20, 22, 24, 31, 32, 34, 43], lack of motivation [26], concerns about risk compensation [13, 17, 20, 24, 32,33,34,35, 39, 41, 43], concerns about efficacy [20], moral concerns [19, 26, 34, 35], poor awareness of regulatory guidelines [26, 44], concerns about side effects [10, 12, 13, 19, 22, 29, 30, 40, 43], concerns about resistance [10, 13, 22], concerns about frequent relocation [29, 30], insufficient health system capacity and infrastructure [19,20,21,22, 32, 37, 44], and cost [10, 20, 22, 29, 43, 44].

14 studies reported on facilitators of HCWs’ attitudes and willingness to offer PrEP. Reported facilitators included: technical competence and training [10, 17, 26, 29, 33, 41, 44], integration into existing health services [17, 29], dedicated PrEP delivery rooms [26], provider experience [10, 11, 16, 26], adequate risk perception [17, 25, 26], younger provider age [10], task shifting and sharing [26, 42, 44], provider desire to encourage patient autonomy [24, 25], and the availability of adolescent-friendly health services [17, 41].

In Mahlare et al., older healthcare workers had higher odds of higher PrEP knowledge. Work experience was not significantly associated with knowledge, attitudes, or practices in this study [14]. This was also seen in Zimamu et al.’s study, where work experience was not associated with improved attitudes towards PrEP [15]. Being male and good provider sexual behaviour were facilitators in Mekonnen et al.’s study [16].

This systematic review included 34 qualitative and cross-sectional studies evaluating the knowledge, awareness, and willingness of healthcare workers in Africa to offer pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). Reported levels of knowledge ranged from 3.5 to 55.7%; awareness levels ranged from 60 to 94.7%; while willingness levels were reported between 26.1% and 86.3%. The included studies were relatively homogeneous in terms of settings, healthcare worker types, and experiences in offering PrEP, enabling the calculation of pooled estimates. The pooled awareness proportion of HCW was high, attitudes and willingness were average, while the knowledge was low, which is of significant concern.

The findings of this review revealed a wide disparity in healthcare workers’ knowledge of PrEP across different studies. While some studies reported low levels, with as low as 3.5– 17.6%, others showed higher levels, with up to 64.4%– 55.7%. This disparity mirrors intra-country disparity in settings such as Australia [16, 45], between the southern states and other regions of the US [46,47,48,49], and intra-region disparity between Brazil and Mexico [50]. The pooled proportion of healthcare workers with good knowledge of PrEP was 18%, highlighting knowledge gaps which may impede PrEP implementation.

Several factors including the differences in the self-rated questionnaire employed by different studies to assess HCW’s perceived knowledge. Another possible explanation for this disparity could be the difference in the availability of specific PrEP policies and the stage of the implementation of PrEP programmes in these countries [16, 50]. Other reasons include poor or limited training opportunities on PrEP [18, 20, 26, 31, 39, 44] and poor awareness of regulatory guidelines [26, 44]. Moreover, the disparity can also be due to the different compositions of HCWs in the included studies, a phenomenon best explained as the ‘purview paradox’ in which each group of healthcare workers believes that PrEP prescription falls in the clinical domain of other workers [51, 52].

While some studies reported positive perceptions of PrEP as an effective HIV prevention strategy, others raised concerns that promoted hesitancy. The overall proportion with positive attitudes was 46%, indicating that most HCWs’ expressed negative attitudes. This is in contrast with studies from other regions with reports of overall positive attitude of HCWs toward PrEP [53,54,55,56,57]. Given PrEP’s effectiveness in reducing HIV incidence [58], this is concerning [58]. However, the overall poor attitude of HCWs towards PrEP is not surprising as studies have reported a significant association between the knowledge and previous training of PrEP and the attitude of HCWs towards PrEP [16, 50, 59]. This suggests that the knowledge gaps among HCWs’ may contribute to their negative attitudes and emphasizes the need for targeted education and skills training to improve HCWs’ trust in PrEP’s effectiveness.

Possible explanations for the negative attitudes of African HCWs’ to PrEP prescription included concerns about risk compensation, where some HCWs feared that PrEP use might encourage high-risk sexual behaviours among patients [13, 17, 20, 24, 32,33,34,35, 39, 41, 43]. This is evidenced by reports of increased risky sexual behaviours resulting in STI acquisition, poor risk perception [18, 34], and concerns that patients will not achieve daily adherence following PrEP use [54, 60]. Also, the moral and cultural beliefs of HCWs’ can possibly influence their attitudes, with some HCWs expressing concerns about prescribing PrEP to adolescent girls, sex workers, or men who have sex with men, populations that are often stigmatized in certain settings [17, 19, 22, 26, 29, 31,32,33,34,35]. While these concerns are understandable, healthcare workers and institutions have significant roles to play in providing adequate information on good sexual behaviours and practices and monitoring PrEP use.

Despite poor knowledge and attitudes, the overall proportion of willingness indicates moderate levels of willingness to prescribe PrEP. This suggests that negative attitudes of HCWs do not necessarily translate to not prescribing PrEP [61]. This is in contrast with studies that revealed that a higher level of acceptance and willingness to prescribe PrEP is associated with good knowledge of PrEP [56, 62]. A possible explanation for the moderate level of willingness is response bias, as HCWs may feel obligated to prescribe based on clinical guidelines [61].

Although several studies reported a high willingness of HCWs to prescribe PrEP, most have residual concerns which are similar to the highlighted barriers to the high willingness of HCWs to offer PrEP. A major concern is the low availability of PrEP and the insufficient health system capacity and infrastructure [19,20,21,22, 32, 37, 44, 63] as PrEP is readily available in a limited number of clinics and pharmacies across African countries. Also, there is evidence that longer consultation time increases the willingness of HCWs to prescribe PrEP [17]. However, workload concerns and time constraints discouraged some HCWs from integrating PrEP into routine practice [21, 22, 31, 32, 39, 44]. As described by a study in the US, 43% of HCWs reported patient concerns about PrEP cost and 27% felt very or somewhat (45%) discouraged from discussing cost and insurance issues [64]. A similar concern is shared by African HCWs [10, 20, 22, 29, 43, 44]. Also, several studies reported that HCWs’ stigmatizing attitudes, especially toward key populations concerning PrEP safety; and concerns about the efficacy, resistance and side effects of PrEP are linked with reduced willingness to prescribe it [10, 13, 20, 22, 54, 61, 65, 66].

This review provides a comprehensive synthesis of 34 studies across several countries with valuable insights into African HCWs’ knowledge, attitudes, and willingness to prescribe PrEP. Our analysis was enriched by the inclusion of qualitative and cross-sectional studies which captured diverse perspectives and identified the key barriers and facilitators influencing PrEP implementation in African countries. We followed the PICO model, adhered to the PRISMA guidelines, and employed the JBI critical appraisal checklists which reinforces our study’s quality, transparency, and rigorous methodology. Moreover, we calculated pooled proportions for key outcomes which improved the study’s clarity and the interpretability of findings. The inclusion of studies from diverse geographic regions and healthcare settings strengthens the generalizability of the findings of this review.

It is important to note that the comparability of the findings of this study is limited by the heterogeneity of the included studies in terms of settings, populations and outcome measurements. The majority of the included studies are cross-sectional in design, which limits the evaluation of causal relationships over time. We recognized the possibility of publication bias as studies with significant findings have higher chances of getting published. Also, the inclusion of only English studies may have excluded relevant non-English studies as the African continent is multilingual. Furthermore, the differences in the assessment method and measurement of the knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of HCWs by different studies may have introduced potential inconsistencies in the pooled estimates. Also, there is the possibility of underrepresentation of certain categories of HCWs including pharmacists and community health workers. Due to data limitations, we did not perform subgroup analyses which hindered detailed explorations of the variations across different professional cadres, countries, regions and healthcare settings. Despite these, this study highlights the critical gaps and opportunities to improve the implementation of PrEP programs across African healthcare systems.

Despite an overall awareness rate of 85%, only 18% demonstrated good knowledge, and positive attitudes were observed in 46%, with willingness to offer PrEP at 58%. These findings show that targeted interventions are needed to address knowledge gaps, promote positive attitudes, and nurture HCWs’ willingness to offer PrEP. Future programs should prioritize comprehensive training adapted to local contexts. Additionally, targeted interventions may be needed to improve HCWs’ PrEP-related competencies and practices across different healthcare settings.

All data generated or analysed during this study are included in this published article and its supplementary information files.

No funding was received for this work.

Because this work did not require the collection of data directly from human participants, ethical approval was not required.

Not applicable.

CRD420250651473.

The authors declare no competing interests.

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Open Access This article is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License, which permits any non-commercial use, sharing, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence, and indicate if you modified the licensed material. You do not have permission under this licence to share adapted material derived from this article or parts of it. The images or other third party material in this article are included in the article’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the article’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0/.

Femi-Lawal, V.O., Olawuyi, D.A., Oke, G.I. et al. Knowledge, attitudes, and willingness of healthcare workers to offer pre-exposure prophylaxis in Africa: a systematic review and meta-analysis. AIDS Res Ther 22, 68 (2025). https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-025-00768-y

Received:

Accepted:

Published:

DOI: https://doi.org/10.1186/s12981-025-00768-y