It was criminal that the Best Animated Film category didn’t exist at the Oscars before 2001. Iconic films like The Little Mermaid, The Lion King, Aladdin, and Mulan missed out on the golden statuette. While Beauty and the Beast became the first animated feature to be nominated for Best Picture, the absence of a dedicated Animated Feature category left a void in recognizing the artistry of animated films at the Oscars.

The creation of the award, in hindsight, inadvertently confined animated films to their own category. Following the 81st Academy Awards, cinephiles noted that no rule prevented Wall-E from being nominated for Best Picture, sparking debates on animated films’ true recognition.

At the time of the award’s introduction, Disney had cooled off, and Pixar (distributed by Disney) took the reins, dominating with creativity and innovation. Pixar has claimed 11 of the 23 Oscars for Best Animated Feature.

Today, the animated landscape is more competitive than ever. Recent winners like Encanto (2022), Guillermo del Toro’s Pinocchio (2023), and Hayao Miyazaki’s The Boy and the Heron (2024) reflect the global appeal of animated storytelling. The 2025 contenders—films like Look Back, Wild Robot, and Memory of a Snail—are garnering praise for their artistic merit, while mainstream titles like Inside Out 2, Despicable Me 4, and Kung Fu Panda 4 will surely resonate with audiences.

Debates over Oscar-winning animated films persist. Some winners have been undeniably deserving, while others spark questions over the Academy’s favoring of crowd-pleasers. Regardless, each winner captures a moment in animation’s evolving story as an art form.

Brave is the story of Scottish princess Merida. She is a born adventurer and seeks a life of thrill in the Scottish wilderness. However, all of that is under threat due to her coming of age. To run from her problems, she sets off a chain of events that requires her to repair the damage of her actions and sets up a path of realization for all parties involved.

One unique thing about Brave is that it is a rare film not from North America to take home the prize. There are very few. This Pixar film doesn’t scream for a re-watch and is not something light. Working in its favor is the animation of Merida’s hair, the message of non-conformity, and the shocking idea of Disney distributed film claiming that love should not be forced upon anyone. These elements may have helped the Scottish film clinch the win over the likes of Wreck-it Ralph or Frankenweenie. Perhaps if some of the films from 2017 or 2019 had been part of this race, things may have been different.

Happy Feet focuses on the Emperor penguin tribe, primarily on Mumble. He is the odd one out, as he can’t sing like the rest, but becomes an excellent dancer. This leads to him getting solace elsewhere, but being exiled from his tribe and going on a journey that becomes serious in the end. Happy Feet has the ending and the message there provoked voters to pick it.

The seriousness of the environmental message, combined with the vibrant colors of the Arctic and the foot-tapping melodies, helps this George Miller directorial avoid the wooden spoon. This film created history just like Shrek did with its win in 2001. Happy Feet became the inaugural recipient of the BAFTA for Best Animated Film.

There is very little subtlety in the way in which directors Byron Howard and Jared Bush approach the cultural specificity and thematic depth of Encanto. It devises the classic Disney princess formula to tell a family-friendly Colombian story of Mirabel, the only ‘unspecial’ individual in a family that consists of only magical beings. Through the story of a matriarch’s miracle passed down the generations, it tells a heartfelt and universally appealing tale of how constricted pressures of extended family work their way to generate feelings of isolation and inadequacy among those who are unable to achieve the promise of extraordinary.

The visual world-building is both immense and immersive- the breathtaking beauty of this fictional setting is inspired by the lush wax palms of Cocora Valley. The way it infuses the family values and social systems integral to the social culture of Latin America is also impressively inclusive, so you don’t mind the film’s unmistakable English-language roots. Yet, the broad generalizations made for magical realism are never less than obvious. Additionally, the dialogue writing is too overt in places, especially in the third act.

Yet, the film largely works because of its effective balance between quirkiness and education in terms of tonality. The twisted knots of a dysfunctional family with secrets are generously revealed. In that process, the wonderful original songs by Lin Manuel-Miranda are incredible in how transportive they are. The way it grounds the story by the climax in which no external magic helps the Madrigals in their journey to rebuild their home is a big improvement over the wish-fulfillment streak of other mediocre Disney/Pixar offerings. Still, the fact that it won over the massively better and more important animated documentary Flee, is a fact that sticks out like a sore thumb.

Toy Story 3 has the perfect ending, right? Well, Pixar and Disney felt that it needed an epilogue. We can’t blame the studio for this epilogue as it is the Toy Story franchise and not Andy Toy Story. To keep viewers intrigued, Toy Story 4 got back a character who was absent in the third installment.

Unfortunately, plenty of other characters (Rex, Slinky, Jessie) got underused in this film. Woody, being obstinate, began to get annoying after a while, but the Toy Reunion and future into the unknown for the sheriff allowed voters to have a pleasing parting memory. The first sequel to clinch the award wasn’t the top contender of the year. 2019 was stacked, and Toy Story 4 occupies a lower spot on the list as it shockingly beat out stellar names like Klaus and I Lost My Body. Will there be an (animated film not just Pixar/Disney) movement to let other films stand a chance? This could even see the most successful combination raise their game and push the boundaries of animated filmmaking even more.

Frozen broke barriers such as not marrying the first person you meet and acts of true love not requiring the leads to kiss. Brave had content along similar lines. The film is light enough for children with a dollop of sinister elements added to proceedings to give it a slight edge. A re-watch (if you can sit through) may be rewarding as you would notice every element that pops up, be it the snowman, the turn, the plot, and the characters; is relevant. But it is the same old Disney.

To be fair to Frozen, even if they had gone ahead with Elsa being the villain, the repetitive nature may have been felt. However, they opted to let ‘Let it Go’ thrive and helped the film remain in voters’ minds. That let them create a complex villain that many may not have been expecting; Frozen teased the idea of the circumstances being the antagonist but also had a primary antagonist. It is one of the most visually stunning films with animators using the ice to let the on-screen visuals shimmer. Frozen also has amazing numbers. While one song builds the story and drops innumerable clues, the second song builds on the clues and the third song touches upon elements from them and lets the animation do its bit to keep it firmly entrenched in everyone’s heads.

Wallace & Gromit: The Curse of Were-Rabbit brought a beloved British cartoon to the silver screen. Focusing on eccentric inventor Wallace and his canine Gromit, the film shows how one invention goes a bit too far, leading the duo to get things right and save their reputation in Tottington.

Blending in horror and comedy, and rejecting computer as well as traditional animation, Wallace and Gromit: The Curse of Were-Rabbit, with its clay-based stop motion format, remains the only stop motion animation to take home the top prize for an animated feature film. Like most years, there have been arguments about other films deserving the top prize, but Wallace and Gromit is a contender that can arm its supporters with a series of arguments to hold off fans of Corpse Bride and Howl’s Moving Castle. Going for a light film to recognize stop motion filmmakers and promote the technique may have motivated voters to go for the British film.

Zootopia clinched the award for 2016, and it would not come as any surprise. The situation at the time and the representation of it in the film was perfect timing. Although the Disney happy ending is seen with dreams coming true, some lines about not having them to avoid being disappointed hit home.

In Zootopia (a play on Utopia), we see a variety of animals living in harmony in different zones, all within one city that seems to take inspiration from Asgard. Films such as The Godfather are also referenced to delight classic cinephiles. Zootopia shows us how we can be different and still live together in harmony. It gives the message that there should be equal opportunity for all. The infusion of a crime/mystery caper adds to the spice of the film that preaches harmony and the idea that sometimes it may be the underdog that is the real foe.

Rango brings to life the story of a chameleon who is cast into an adventure in the Wild West. The sight of Rango in this list may make you wonder what went wrong. It is so different from all the other entries in this article. Well, an explanation could be that no Pixar or Disney film made it to the Dolby Theatre as a nominee in this category.

Rango beat out the likes of Puss in Boots, A Cat in Paris, and Chico and Rita to clinch the top prize. What may have helped it is the fusion of the classic Western genre into an animated effort. This one needs to be appreciated way more.

Being careless and clumsy is something that can have serious ramifications. Having worked all his life, Joe Gardner finally landed a gig as a jazz player. However, after an accident, he gets sent to limbo, where he has two options. Head to the Great Beyond or help a soul get a pass at the Great Before to head to Earth.

Joe somehow lands on the latter and gets the perfect soul to help/ help him out. While this is an impediment, it is the challenging 22 that got him to take the journey to find his body, help her discover her spark, and save two souls. The idea of finding a purpose is touched upon here, and it is only when a thing is done, you realize that what you were doing is what the purpose is. Soul also conveys to the audiences that the simplest and mundane things, things that just seem to happen, could be what enhance the beauty of our lives in any small way.

At a cursory glance, Mark Gustafson and Guillermo Del Toro’s adaptation of the iconic Carlo Collodi fable about the wooden child who came to life promises to be a dark and grueling social take on a narrative that was stuffed with the colorful and childproof giddiness of popular culture. However, anyone who goes in expecting a bleak anti-fairy tale from the film is going to be heavily disappointed because, despite the stop-motion goth aesthetics, it is relatively milder. This, perhaps, also goes a long way to explain winning an Oscar.

The story indeed finds itself set in the Mussolini-era Italy, but it is also bleached of the complexity and nuance one might come to expect. This still does not stop the film from being brilliant, because its technical polish is complimented by beautiful flourishes of heartwarming writing. The film revels in a grounded and lived-in father-son story, which is drenched in the kind of simplistic entertainment that is one for the ages.

What makes Guillermo Del Toro’s film important is how it doesn’t fail to double up as an anti-fascist cautionary story despite the limitations. It plunges into and openly addresses its politics, which grants the film the necessary leverage and tools to become an anti-war fable. Its wise narration (done by an impeccable Ewan McGregor) also makes you admire its world-building, which is considerably rugged but not difficult to warm up to. If you look closely enough, the film is also awash with mature existentialism in its undertones.

Shrek 2 may feel like the film that picks off fast, but Shrek is where it all began. This DreamWorks Animation offering introduced us to characters like Fiona, Shrek, and Donkey and allowed numerous fairy tale crossovers to grace the screen for a true cartoon fantasy delight. It focuses on Shrek, who just wants to be alone, but is forced to embark on a journey to reclaim his swamp. En route, he meets Donkey, Dragon, and Fiona and realizes that companionship may not be a bad thing after all.

Shrek, the first animated film to win an award for a non-song and non-technical category, has aged well. The re-watch value of this film is high as the origin story of the trio is something that you may never tire of seeing. The only reason it is this low is that some other films have pushed the boundaries of animation and eclipsed the maiden recipient of the award.

The Incredibles focuses on the Parr family who needs to hide their powers as public opinion is against superheroes. Now, which superhero film after 2005 has not copied that? This Brad Bird film featured the superhero team-up, the prospect of misuse and dealing with powers, and having to do the right thing.

It has no in-your-face themes like some of the other entries on this list. Instead, The Incredibles is just a delightful classic superhero film where good takes on evil and presents a bunch of entertaining scenes by taking advantage of the animated format and each character’s unique ability.

Riley is a young child who crafts innumerable happy memories in Minnesota. These are the result of emotions Joy, Sadness, Denial, Anger, and Fear combining and controlling her. However, after a move to the West Coast, things get problematic, forcing the emotions to come up with solutions and save the memories of the past. Some solutions show that it’s okay to be sad, and an excessive feeling of a single emotion can provoke the overwhelming surge of another emotion.

The concept of emotions having emotions helped cater to the adults without getting it too complex for the young audiences. Also, the idea of the mind depicted as a control room and literal concepts such as the memory train and memories being an amusement park were nice touches. The idea of long-term memory (storage), subconscious (problematic memories), and the dream studio (as dreams are the inspiration for something we have seen) proves to be creative.

This will be the year that “Kubo and The Two Strings” and “Loving Vincent” lost, rather than the year “Coco” won. “Coco,” which focused on Miguel’s need to enter the land of the dead, was predictable- you knew Hector had to be someone who was someone close to Miguel. The positioning of Ernesto de la Cruz as the villain also seemed expected, as it was obvious. It was also borrowed from Up, where the greatest idol turns out to be a villain who has a secret to protect- no matter the cost.

However, what helped Lee Unkrich claim the statuette was his ending. The sight of Hector reuniting with Coco and Imelda and being able to cross the flower bridge was something that gave a sense of accomplishment to young individuals and managed to bring a tear to the eyes of the older audiences. Individuals across all age groups will have grooved to ‘Remember Me’ and ‘Poco Loco’. The dazzling colors of the town across the flower bridge will have also helped “Coco” be remembered at the time of voting.

“Big Hero 6” focuses on Hiro Hamada, a tech prodigy who wants to push the boundaries of his imagination. However, after he refuses to sell his technology, tragedy strikes and claims his elder brother and his mentor’s life. Depression takes over, but BayMax enters and connects Hiro with his friends as they try to save San Fransokyo from doom. This film has entertainment, themes for nature audiences to resonate with, and a cool superhero and supervillain vibe that makes it something both voters and casual audiences would devour.

BayMax is a shining point in this film. His subtle PSA, thanks to his characteristics as a medical robot, proves to be quite useful and hilarious given the situation in which he delivers them. This helps “Big Hero 6” get in a few laughs, even while treating audiences to a high-speed edge-of-seat chase scene. BayMax’s bond with Hiro is what lends weight to the gut-wrenching sequence in the final 15 minutes. His innocence in everyday situations/interactions is also something that leads us to remember him.

“Toy Story 3” was the third animated film to get the nod for the main prize at the Oscars (83rd Academy Awards). It focuses on the adventures of Buzz, Woody, Jessie, and the gang nearly eleven years after the adventures of Woody nearly getting stocked as a collectible. Nostalgia played a key role in this film as it drew back the audiences who would have aged considerably since “Toy Story 2.”

These cinemagoers may have resonated with the concept of toys being forgotten and reminisced about the days they played with toys that now just sit on shelves. Perhaps they may have had a sense of Déjà vu at the climax? This should have been the perfect send-off for the “Toy Story” franchise. Randy Newman’s song conveyed the film’s message of time passing by nicely. The ideas of growing up, acceptance, and handing over were explored. The dash of literal humor involving Rex and the Potato Heads is the icing on the cake for this film.

“Finding Nemo” is a take on how over-protectiveness can be harmful. It also is a story about familial bonds and the promises that see no journey too tedious. Marlin and Dory’s journey across the sea as they just kept swimming, presented audiences with color, catchy quotes, and an exploration of the sea and sea creatures. The characters are delightful with the bubbly Dory bringing in energy and excitement on the journey to “P Sherman, 42 Wallaby Way, Sydney.”

“Finding Nemo” has a subtle hint to save the oceanic flora and fauna, and who can ever forget the murder theme from Alfred Hitchcock’s 1960 masterpiece once Darla makes her entrance?

“Up” is an adventure comedy that was the second animated feature to be named among the year’s best films. It was more than an animated treat for children as it presented common themes of growing old and stubbornness. However, it waters them down and presents a little bizarreness (after all, “Up” is an animated film) to keep younger audiences transfixed and eager to see Charles Muntz lose.

The adventure was fun; the scenes featuring Russell, Kevin, and Dug are a delight, but what makes “Up” thrive is the scene that gives this film its momentum. Confused? Michael Giacchino’s music, accompanied by the touching tale of Carl and Ellie, shows us the old man’s passion to keep his “cross your heart” promise.

Before MasterChef became a thing, “Ratatouille” was the film that may have served as an inspiration for many chefs. Or, perhaps it may have given humans the idea that “Anyone can cook”. It also presented a beloved French dish to the world.

Focusing on Remy, it blends the anthropomorphic usage of animals and converts humans into puppets to put forth the ideology that anyone can cook while overcoming physical obstacles that would impede them. Elements such as jealousy, regret, and belief make this much more than just a film about a rat that can cook (to do that in itself was quite remarkable). Rather, they come together and convince audiences to savor it, just like how Anton Ego devoured his Ratatouille.

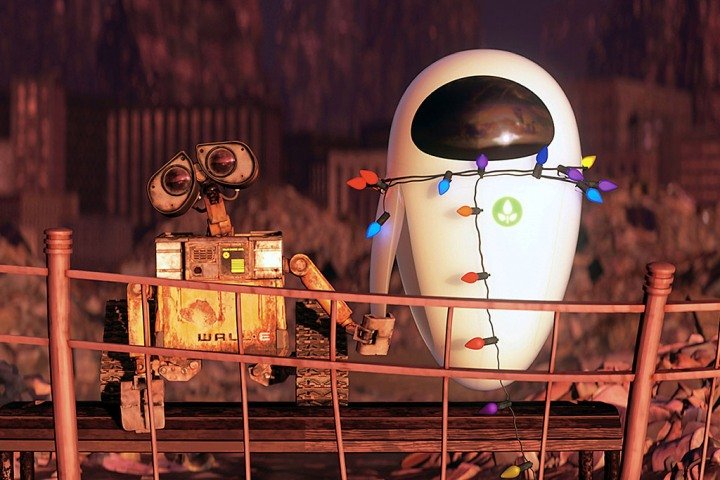

A story about human instincts transferred onto robots and a mirror of laziness combined with a glimpse into the impending future due to greed and the need to extract everything possible and destroy the source, “Wall-E” deserved more than a win in the Best Animated Film category. Had it received the push, it may have even given “Slumdog Millionaire” a run for its money.

“Wall-E” did its bit in reopening a discussion about animated films supposedly not being allowed to feature in the Best Film category. The effort was so good and so delightful that it opened the floodgates for films such as “Toy Story 3” and “Up” to make it to the Best Picture shortlist.

Latvia’s official submission to the Academy Awards and the first film to be nominated in both Best Animated Feature and Best International Feature, “Flow” (Straume) finds its rhythm in silence. In a world swallowed by rising waters, a lone black cat navigates a post-apocalyptic landscape devoid of humans, its survival hinging on instinct and reluctant companionship. Made with open-source software Blender on a modest $3.5 million budget, director Gints Zilbalodis crafts a story that is, at once, a coming-of-age odyssey, a found-family drama, and a meditation on the unease of coexistence.

Rather than drowning in allegory, “Flow” embraces an adventurous, video game-like aesthetic and a quiet sense of humor, sidestepping the usual moralizing that plagues narratives about humanity’s collapse. Paradoxically, the absence of civilization makes the film feel deeply, achingly human. Where animated films often strain to manufacture warmth, “Flow” finds it effortlessly—in a cat’s meow, a capybara’s squawk, the rustling of feathers. It tugs at the heartstrings with no words at all, and it succeeds marvelously.

No prizes for guessing that this would be the best animated film to win the Oscar. A gripping story combining superheroes from different universes (six different spider beings), a message about inclusion and sacrifice, and a fusion of different types of animations; “Spider-Man: Into The Spiderverse” is an absolute delight.

Films usually have a cartoon feel, or take the characters from the page and make them extraordinary on the big screen. However, “Spider-Man: Into the Spiderverse” takes audiences into the comic book and gives them undoubtedly the best Spider-Man movie of all time.

“Spirited Away” is a gem of a film that showcased the idea of elite animation and endearing stories being available in places not called North America. It focuses on Chihiro Ogino and her unfortunate journey to the spirit world. Once there, she must strive to survive and do her best to get out with her parents. “Spirited Away” is a rare Oscar winner that blends fantasy and beautiful exoticism. The hand-drawn animation helps “Spirited Away” stand out as the characters don’t look perfect in any way. However, their behavior with one another touches the heartstrings of the audience.

Case in point: the scene where Chihiro remembers her name and learns that she needs to grind hard. The beautiful sequence of Chihiro and Haku in the air combined with Joe Hisaishi’s music after her trials in the bathhouse and journey to free the Spirit of the Kohaku River is what tied a neat bow on this Hayao Miyazaki film.

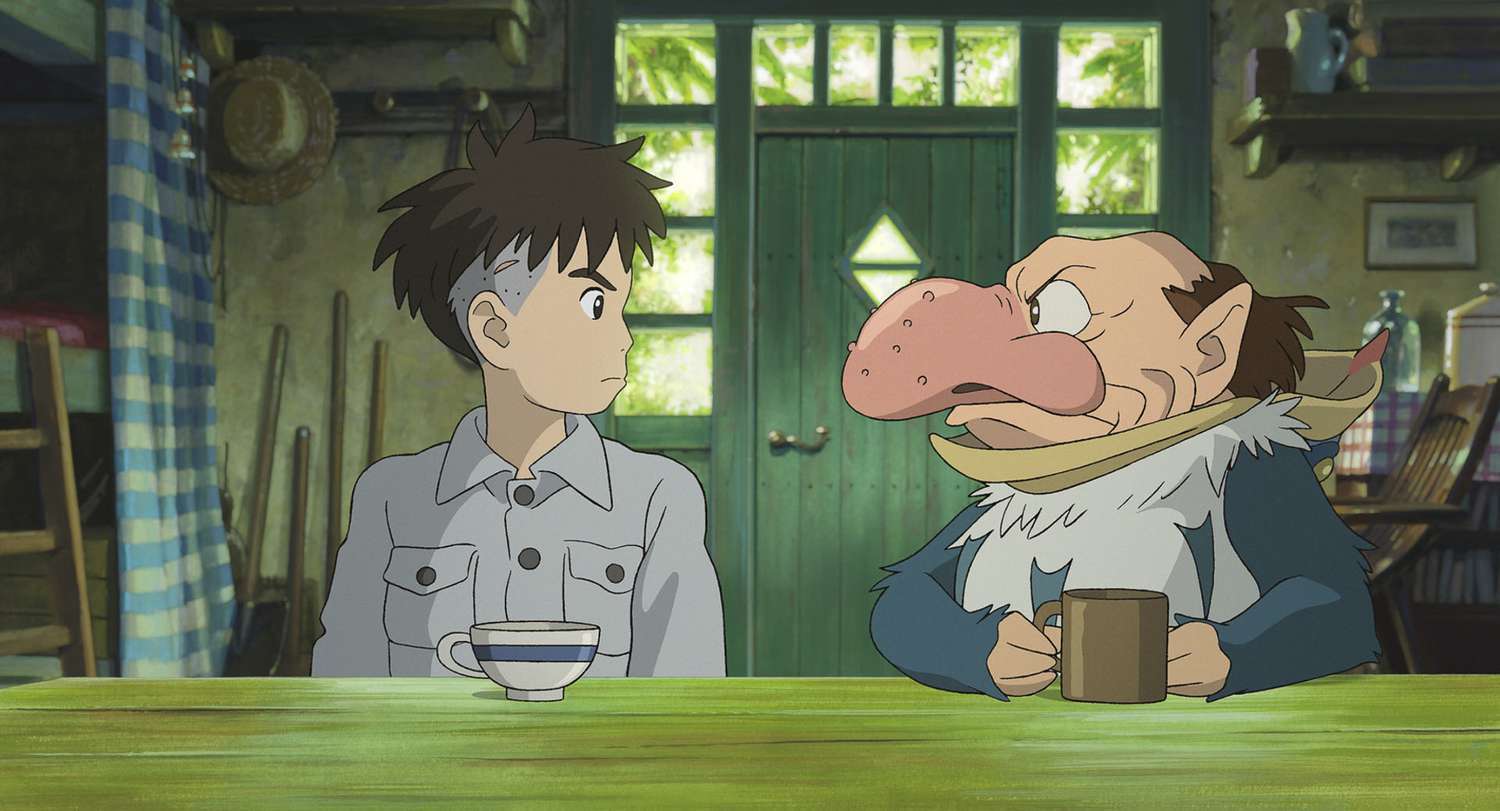

Despite the film festival traction that it garnered over the year, the Best Animated Feature Film win of Hayao Miyazaki for “The Boy and the Heron” still stands as an unexpected if also a completely welcome surprise in the annals of the Academy. Accessibility is not something that Miyazaki’s latest would be remembered for. If anything, the film is so deeply immersed in the various mythology, embedding it with sparkling motifs of adventure and fantasy, that every proceeding of the film will be open to a wealth of interpretations. The whole journey from the beginning to the end is to be taken as a well-rounded symbolism.

For some, it is a film that uses cleverly coded characters such as birds, animals, and castles to comment on the sustainability of art in the ongoing studio system. Some others will take it with a pinch of existentialism, viewing it as Miyazaki’s intimate self-critique. It also works very well as a profound generational tale that is at the same time grounded and taking the leaps of escapist fantasy.

Either way, the film finds itself in a World War II backdrop, and it quite organically weaves the tale of a young boy who is gradually adjusting to his new mother. While the adjustment and familial acceptance take their own naturalistic pace, the plight of an entire world finds itself locked in a crumbling tower. Once inside, the surreal visions tend to create astonishing novelistic depth.